Raj Pandya and Steve Ackerman, co-chairs of the AMS Annual Meeting this week in Seattle, wrapped up their show with Episodes 4 and 5, now up on YouTube. Raj and Steve took their production team and throngs of groupies into the Exhibit Hall in search of tips on communicating from those master communicators, the people who represent the products meteorologists invent and use:

The next day our intrepid co-chairs finally had a moment to themselves and opportunity to get to know a little bit about each other’s day jobs via the standard professional communique-in-a-nutshell…the elevator talk:

Jeff

Jeff

Making the Public Aware of the Science

by Skyler Goldman, Florida Institute of Technology, Student Contributor

I sometimes feel like the whole purpose—or at least the effective application—of meteorology depends on being able to communicate to people who are not as knowledgeable in our subject. And yet the difficulty of this task is overwhelming. This was acknowledged from the outset at the Presidential Forum on Monday.

“We don’t serve you, the scientists, very well, and I want to change that,” Claire Martin, the chief meteorologist of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation said of the communication between scientists and the public. It’s an important statement, and one that seemed to be agreed upon by the rest of the panel.

“Scientists live and die by how their work is represented,” Tom Skilling of WGN Chicago said, adding that if they are not represented well, then they have no interest in communicating with the broadcast meteorologists and other meteorologists who communicate with the general public. It’s an issue facing our entire field, especially with important climate change topics knocking on the door.

It’s a simple concept: if the scientists who are doing the work of studying our changing climate are not getting the credit they deserve nor getting their entire story out there accurately, then they could lose interest in dealing with those responsible for communicating the science. In a society of three-minute weather broadcasts and one-page weather reports, it’s a delicate balance between telling the whole story and leaving something out. Someone—either scientists or journalists—is not going to get their way. So how does our field get around it?

An audience member threw out an interesting point. If the public is paying for the research, then shouldn’t they be able to read the work in a language they understand? This scientist cited a paper he wrote in “regular” English as opposed to “scientific” English, and said that it was instantly rejected by the editor for sounding too “unintelligent.” This scientist suggested that journals publish two versions of every paper, one for the scientific community and one for the general public.

The idea is somewhat revolutionary, and it was denounced by another scientist who claimed that he wasn’t sure that the public would even “care about his work.” Why go through the trouble?

But shouldn’t the public get to decide what they care about? I think those of us in the sciences tend to overlook just how intelligent the public can be. Making more scientific work available to the public in plain language would increase awareness. Then, of course, the public would need to have access to such articles. Unless you’re in college or working in the field, you’re probably not even aware that these journal articles exist, let alone have a subscription. It’s not like you can browse meteorology journals at Barnes and Noble or Borders. Access to science should not be limited by a caste system based on wealth or education. It should be available to all so the public can make their own decisions. Perhaps the public would be better prepared for weather and climate if they could form their own opinions.

Tom Skilling said that we as meteorologists “haven’t done a good job of preparing the public [for climate change].” Martin Storksdieck added that we “have done a poor job of telling not only what we can do, but what we can’t.” Perhaps the scientists wouldn’t be misrepresented if the general public could read their work. Maybe we don’t have to re-write articles as the one scientist suggested, but it would be a start. Sure it requires more work, but whoever said communicating was easy?

The Raj and Steve Show, Episodes 2 and 3

Your Conference Co-Chairs, Raj Pandya and Steve Ackerman, have been gleaning insights into the communication of weather and climate during the meeting. Episodes 2 and 3 of their continuing quest for Annual Meeting wisdom are available on the Ametsoc YouTube channel. In Episode 2, Steve (sensitively acknowledging Raj’s letdown of expectations for the Chicago Bears) talks about how science-driven information sometimes unintentionally creates high expectations for certainty when in fact uncertainty is a key to using such information wisely:

Then in Episode 3, Raj notes that scholars continue to puzzle over the communicative power of pictures, but have a firm grasp of the power of the word. Words, Raj points out, have the power to create pictures of their own, ultimately trumping numbers in their ability to motivate and convince an audience:

Nationwide Network of Networks–Now Is the Time for Your Input

by George Frederick, Chair, AMS Ad Hoc Committee on Network of Networks

Today’s Town Hall (WSCC 606, 12:15-1:15 pm) on the Nationwide Network of Networks (NNoN) coincides with the availability of a draft report by our committee, available online for comment and review.

The report is a result of the AMS’s intensive response to the 2009 National Research Council (NRC) report entitled, Observing the Weather and Climate FROM THE GROUND UP A Nationwide Network of Networks. It summarized the work of a committee of the NRC’s Board on Atmospheric Sciences and Climate charged with developing “…an overarching vision for an integrated, flexible, adaptive, and multi-purpose mesoscale meteorological observation network….” In “… identifying specific steps…that meet(s) multiple national needs…” the committee was given five guidelines:

- Characterize the current state of mesoscale observations and purposes;

- Compare the US mesoscale atmospheric observing system to other observing system benchmarks

- Describe desirable attributes of an integrated national mesoscale observing system;

- Identify steps to enhance and extend mesoscale meteorological observing capabilities so they meet multiple national needs; and

- Recommend practical steps to transform and modernize current, limited mesoscale meteorological observing capabilities to better meet the needs of a broad range of users and improve cost effectiveness.

The committee focused on the planetary boundary layer extending from 2 meters below the surface to 2-3 kilometers above in the United States, including coastal zones. Forecast time scales ranged up to 48 hours. It considered the roles of federal, state and local governments as well as the private sector. The goal was to guide development of “an integrated, multipurpose national mesoscale observation network.”

In reaction to the NRC report the AMS formed an ad hoc committee under its Commission on the Weather and Climate Enterprise to address the report’s recommendations and provide venues for community discussion and response. The committee launched its effort at the AMS Community Meeting in Norman, Oklahoma, in August 2009. Subsequently, six working groups have been busy addressing the recommendations in the NRC report.

The committee shares the vision of the NRC study, in which, ultimately, a “central authority” is required for the success of any nationwide network of networks. Traditional public-private-academic relationships will need to adjust to this new way of doing business—this will be a challenge for the entire community.

Other key recommendations include

- A stakeholder’s summit should be convened at an early date to foment the NNoN initiative and continue the momentum achieved to date. Implementation plans should be a follow-on result of this summit.

- As funding for a NNoN will be a challenge, an implementation strategy should be developed that prioritizes systems based on their economic benefits; e.g., it was evident that systems to improve observations of the earth’s boundary layer would benefit multiple users (wind energy, aviation, forecasting onset of convective activity) and should be given a high priority.

- Ongoing R&D and treating all networks (new and old) as perennial testbeds will be essential to success in constantly assessing and improving the member networks of the NNoN and developing new and innovative methods for observing earth’s boundary layer.

- That the NNoN adopt the Unidata Local Data Manager to provide the communications backbone for the NNoN.

- Metadata will be mandatory for applying data from the NNoN, and a combination of ISO 19115-2 and SensorML is recommended for the NNoN’s adopted metadata standards. Minimal and recommended sets of metadata elements should be adopted and well documented by the NNoN

- The human dimension must be considered when developing the NNoN and is key to engaging stakeholders and network operators as the market is developed. User assessments and education will be key parts of this effort.

State of the Union STEMwinder

by William Hooke, Director, AMS Policy Program, from the AMS project, Living on the Real World

Stemwinder? An old-fashioned mechanical watch needing winding. Now there’s a word that probably will disappear from the vocabulary in a few more years! Dictionary.com tells us that it’s also old slang for “a rousing speech, especially a stirring political address.”

But STEM itself is an acronym that will be with us for a while. It refers to Science-, Technology-, Engineering-, and Mathematics education.

President Obama’s speech last night called all this to mind. Partisans found much in his talk to like. And one area of emphasis was STEM education. An excerpt:

Maintaining our leadership in research and technology is crucial to America’s success. But if we want to win the future – if we want innovation to produce jobs in America and not overseas – then we also have to win the race to educate our kids.

Think about it. Over the next ten years, nearly half of all new jobs will require education that goes beyond a high school degree. And yet, as many as a quarter of our students aren’t even finishing high school. The quality of our math and science education lags behind many other nations. America has fallen to 9th in the proportion of young people with a college degree.(Emphasis added). And so the question is whether all of us – as citizens, and as parents – are willing to do what’s necessary to give every child a chance to succeed.

That responsibility begins not in our classrooms, but in our homes and communities. It’s family that first instills the love of learning in a child. Only parents can make sure the TV is turned off and homework gets done. We need to teach our kids that it’s not just the winner of the Super Bowl who deserves to be celebrated, but the winner of the science fair; that success is not a function of fame or PR, but of hard work and discipline.

Our schools share this responsibility. When a child walks into a classroom, it should be a place of high expectations and high performance. But too many schools don’t meet this test. That’s why instead of just pouring money into a system that’s not working, we launched a competition called Race to the Top. To all fifty states, we said, “If you show us the most innovative plans to improve teacher quality and student achievement, we’ll show you the money.”

There’s more to the president’s speech, but this gives the flavor. He is right to emphasize education. Most of us want to see American values maintained, advanced, and extended throughout the remainder of this century. If we were the most populous country in the world, perhaps we could tolerate a mediocre educational system and achieve such aims through sheer force of numbers. But given that we add up to no more than a few percent of the world’s people, we must ensure that our science and engineering are cutting edge. We must create and innovate. And for the world’s sake, the best of our accomplishments should contribute to sustainable development – new energy technologies; better understanding of Earth processes; greater use of renewable resources; knowing how to protect the environment and ecosystems.

Even were we the best in this arena there would be no cause for complacency. But lagging behind other countries with respect not just to STEM education but also attainment of college degrees? This is truly alarming. Such decline in educational standing is probably the most reliable leading indicator that future U.S. fortunes and U.S. standing in the world will decline in years ahead. A November post on Living on the Real World describes how an emphasis on Earth science in public education would help reverse this threat.

Here the American Meteorological Society can hold its head high. For decades Society staff (led initially by Ira Geer, and now by Jim Brey), and a vast and committed network of teacher-collaborators across the country have made Earth science accessible to American public-school students. This week at the Annual Meeting the 20th Symposium on Education was causing a lot of hallway buzz. Participants were finding the sessions especially lively and energizing. Are you one of their number? Are you working at one of the federal agencies – NSF, NOAA, NASA, the Navy, and others – who have supported this work? You should take special satisfaction in your contributions to world well-being.

Others of you should be pleased at this recognition for your efforts as well. James R. Mahoney (Chair), Martin Storksdieck (Director), and others standing up the new NAS/NRC Climate Change Education Roundtable should give yourselves a pat on the back. Are you working in the education programs of any of the federal agencies? Enjoy the moment. But in a sense, all of us in this community, as well as the media who cover our stories, are donating dollars, thought, and effort to this great cause. We should all feel good.

And then get back to the task at hand!

Photos, Photos, and More Photos

Pictures are up on the Ametsoc Facebook photo albums! Here’s just a sampling, from Sunday’s WeatherFest. Don’t forget to check back there for more updates later today and throughout the week.

Science, the Write Way

by Emily Morgan, University of Miami-Florida

Writing is a form of expression that has become a difficult task for members of the student scientific community. This is not a remark on the basic skill set for a meteorology student, but rather a result of neglect. A huge part of the academic field focuses more on computer-aided analysis, modeling, computation and processes that can very readily led themselves to good writing but often don’t, perhaps because it’s so much more convenient to move on to the next task without explaining the first.

I’ve often wished the science courses I’ve participated in included an increased focus on written analysis of topics, even just simple written forecast discussions or responses to research results, so that we become more familiar with expressing ourselves concisely and fully to a broad audience. It boils down to trying to communicate through a medium that cannot rely on facial expressions and you-know-what-I-mean’s. There is no “question and answer” session after the essay, aside from disgruntled and confused e-mails from readers, and the writer cannot instantly respond to the blank faces of his readers. So the readers, not able to grasp the main theme of the writing, leave the writer without an audience for his point. A terrible fate this is, as writing in science has vital purpose: to convey important research findings, to apply for funding to allow research to flourish, to explain a complex process to students at any level. So why is this form of communication neglected, shunned, even dreaded?

Dr. David Schultz, presenting “Practical Advice for Students and Scientists,” addressed some of my concerns. His seminar focused on commanding, concise titles and effective abstract writing, his mindset being that these are components of a paper that are the most relevant to the reader, who should be the main focus of the paper. His fourth and final rule of writing was “We write for our audience, not for ourselves,” something he reiterated throughout the seminar. He presented a relationship between an effective writing process and an effective forecasting process, where both benefit from a constant narrowing in focus from broad scale ideas to microscale changes. Active writing, rather than passive writing, he claims, is a much more effective way to write. Not all in attendance were comfortable with these ideas, claiming that they’ve always been told to use the passive voice and including anything in first person is seen as unprofessional. One individual was in awe that Dr. Schultz would even suggest replacing the phrase “it was suggested that” with the phrase “I think.” I believe that it is this mindset that continues the difficulty of embracing scientific writing and it was very inspiring to see someone who was intent on easing people out of these bad habits.

Finally, in what I believed was his most important point, he urged the room to “treat all your writing as if it counted.” So it was wonderful to hear this from Dr. Schultz as a reassurance to a sometimes-bewildered writer. Writing can be an intimidating affair, even with the right skills, so to bolster one’s confidence with the thought that this writing does, in fact, matter can be the difference between long, wishy-washy reports and strong, concise writing.

Editor’s note: David Schultz is conducting a workshop, “Eloquent Professional Communication,” Tuesday, 1:30 pm-3 pm, WSCC 3B. He is also presenting “Best Resources for Communication Skills for Scientists” at the Atmospheric Science Librarians International session, 8:45-9:45 am Wednesday, WSCC 304.

A Passion for Mentoring

by Emily Morgan, University of Miami-Florida

Saturday afternoon, I literally almost bumped into Kenneth Carey, who quickly introduced himself as one of the AMS Beacons. He followed my fellow students and me up to our next seminar in the Student Conference. He was very charismatic, very animated, and quite welcoming to a first-time student. Within the first few minutes, he launched into his passion for mentoring and both what it means to him and what effects he has seen it have on others. It was very interesting to hear him laud this communal support separate from any one organization; it really made his argument sincere.

Presenting on “Success in the Job Market,” Mr. Carey welcomed students with a display of many opportunities, urging them to be resourceful and keep their eyes open for opportunities in both federal and private sectors. The most interesting part of his presentation was his list of “10 Skills to Succeed.” All were sound points:

10. Pursuit of excellence.

9. Persistence.

8. Ability to work with others.

7. Innovation.

6. Decision-making.

5. Ability to get things done.

4. Networking.

3. Balance, relaxation.

2. Writing.

1. Public speaking.

Mr. Carey provided much advice for honing these skills, but following this slide, he spoke again about mentoring, whether being a mentor or the mentored. Because of his passion or his persistence, I was sincerely moved by his presentation. It seemed that his only goal was to benefit the meteorological community by encouraging its members to occasionally think of the whole, rather than its parts. Often we can get lost in our own goals and forget that the student beside you has them as well. More so than improving on decision-making (Point 6) and persistence (Point 9), I have become convinced that sharing and working together with my colleagues (Point 8!) will bring me success.

Special Session Today on the 2010 Icelandic Volcano Eruptions

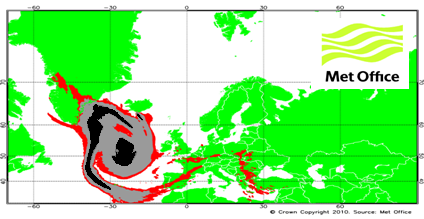

The Eyjafjallajökull volcano eruption in Iceland lasted from the 15 April to 25 May 2010. In addition to threatening local people and their livestock, the volcano sent an ash plume to heights of up to 26,000 feet. Due to the weather conditions, the plume spread over a large part of Europe. Because volcanic ash can cause airplane engines to fail, the plume disrupted aviation over several weeks.

Weather Services played a key role in predicting the spread of the ash and advising the aviation industry. The forecasts were based on safety thresholds for flying through volcanic ash set by the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) along with the national aviation authorities and aircraft manufacturers.

Scientists modelled the evolution of the ash cloud using dispersion models and trajectory models. The model predictions were compared with observations from satellites, aircraft and ground-based networks.

The eruption of Eyjafjallajökull presented challenges to the meteorological community, especially in Europe. The event highlighted the importance of enhanced international coordination to ensure a consistency of approach in the observation, forecasting and dissemination of volcanic ash information and warnings.

At the AMS annual meeting, papers covering the observing, forecasting and warning to the public and especially to the airline industry regarding the effects of the eruption of Eyjafjallajökull will be presented today (Monday) at the Special International Applications Session 1B: The Eyjafjallajökull Volcanic Eruption of 2010 (1:30 pm). At 2 pm Ian Lisk of the UK Met Office talks about how the aviation industry, grounded by safety rules, put pressure on meteorologists to produce ash concentration charts to supplement the normal information from the Volcanic Ash Advisory Centre in the UK. This was an added burden on dispersion modeling services (with the NAME model), but the results proved promising:

The largest uncertainty in the computer modelling of ash dispersion and transport is the ability to accurately reflect the status of the eruption at model initialization. This is less of a modelling issue and much more a case of being able to accurately and safely observe what the volcano is doing in real time, in particular, the:

•Height, diameter and time variance of eruptive column;

•Assessment of ash concentration and particle size/distribution;

•Ash deposition close to the volcano i.e. ash that is not available to be transported.

Unlike atmospheric phenomena, volcanic eruptions are in fixed places and don’t condense or disappear out of thin air, like atmospheric phenomena…but apparently observing them isn’t much easier.

Congratulations, Student Sleuths!

The student conference contest had a happy ending, it just ended a little sooner than mere mortals would expect. Torey Farney, of Cornell University won First Prize before 4 pm Saturday by managing to anticipate the answer before the announcement of the last clue…something to do with mathematically narrowing the range of possible answers and inspired guesswork. Or was that ESP (Earth Science Perspicacity)? His prize was a free travel and registration for next year’s Annual Meeting in New Orleans.

The student conference contest had a happy ending, it just ended a little sooner than mere mortals would expect. Torey Farney, of Cornell University won First Prize before 4 pm Saturday by managing to anticipate the answer before the announcement of the last clue…something to do with mathematically narrowing the range of possible answers and inspired guesswork. Or was that ESP (Earth Science Perspicacity)? His prize was a free travel and registration for next year’s Annual Meeting in New Orleans.

Camaron Plourde, of Embry-Riddle University, also answered early, winning Second Prize (an Amazon Kindle); and Leah Werner, of Embry-Riddle, won Third Prize (an Amazon gift certificate).

Not that they were the only ones to answer correctly. Some 80 percent of the attendees solved the quest.

Meanwhile, in a related drawing, Gavin Chensue, Univ. of Michigan won a copy of the AMS book, Eloquent Science, by David Schultz; and Adam Atia, City College of New York, won a copy the recently published AMS book, History of Broadcast Meteorology, by Robert Henson.

Thanks to AMS’s co-sponsors in the Weather Quest, Atmospheric Science Librarians International and the University of Wisconsin-Madison, for the great prizes.