National Weather Service offices in Missouri and Kansas recently initiated an experiment testing new tornado warnings that combine more specific information with more descriptive language than have been used in the past to describe the potential effects of storms. The experiment is called “Impact Based Warning,” and is meant to bluntly tell residents in the path of tornadoes what could result if they don’t seek shelter. By using phrases such as “complete destruction” and “unsurvivable if shelter not sought below ground,” the NWS is hoping to “better convey the threat and elevate the warning over a more typical warning,” according to Dan Hawblitzel of the Pleasant Hill, Missouri NWS office.

The new alerts got their first big test last weekend when more than 100 twisters were reported in Kansas, Oklahoma, Nebraska, and Iowa. While the NWS’s Storm Prediction Center issued a warning of possible life-threatening storms in several midwestern states days before they touched down, in Kansas the words used in the new alerts were particularly trenchant: “You could be killed if not underground or in a tornado shelter. Many well-built homes and businesses will be completely swept from their foundations.” And the warnings seem to have worked. Despite the large number of storms, only six people were killed—all in an overnight tornado that hit Woodward, Oklahoma. In Wichita, Kansas, a twister tore through a mobile-home park during nighttime hours, but there were no fatalities.

The Impact Based Warning experiment was developed by the NWS in consultation with social scientists. Along with the new vernacular, it includes some key additions to regular tornado warnings, including information that identifies the hazard (hail, winds, tornado, etc.), indicates whether the hazard has been spotted by radar or by people on the ground, and describes potential effects of the hazard (loss of life, damage to trees or buildings, etc.). The warnings can be used not only for tornadoes, but also to signify life- or property-threatening thunderstorms. The experiment is scheduled to run through the end of November, at which point it will be evaluated and considered for more widespread use.

The initiative comes  just one year after tornadoes killed more than 500 people in the United States—the deadliest season in almost 60 years. The 2011 year in tornadoes is examined in the new AMS book, Deadly Season: Analysis of the 2011 Tornado Outbreaks, by Kevin M. Simmons and Daniel Sutter. The book is a follow-up to the authors’ Economic and Societal Impacts of Tornadoes, published by AMS in 2011. The new title looks at possible factors contributing to the outcomes of 2011 tornado outbreaks, including assessments of Doppler radar, storm warning systems. and early recovery efforts. Both books can be purchased here.

just one year after tornadoes killed more than 500 people in the United States—the deadliest season in almost 60 years. The 2011 year in tornadoes is examined in the new AMS book, Deadly Season: Analysis of the 2011 Tornado Outbreaks, by Kevin M. Simmons and Daniel Sutter. The book is a follow-up to the authors’ Economic and Societal Impacts of Tornadoes, published by AMS in 2011. The new title looks at possible factors contributing to the outcomes of 2011 tornado outbreaks, including assessments of Doppler radar, storm warning systems. and early recovery efforts. Both books can be purchased here.

News

The Revolution Needn't Stop Now

In 2005 researchers from NCAR and the University of Colorado decided to change the weather community. They started a program called, “Weather and Society*Integrated Studies”, or WAS*IS. As the name implies, what “was” is no longer good enough. This unique program started with a workshop aimed to entice physical and social scientists to enter a room because of their separate agendas, yet emerge having formed unexpected alliances in solving common problems. The workshop quickly grew into a grassroots movement. That movement is now a revolution in progress, facing its greatest challenge so far.

WAS*IS encourages students, researchers, and practitioners in the weather community to see that they can make progress by taking interdisciplinary approaches. Organizers realized that meteorologists have burning questions that require social science methods, and social scientists often have questions that require physical science understanding. This required a fundamental shift in the way we approach the goals of the meteorological community. Julie Demuth of NCAR and her colleagues explained in the November 2007 BAMS,:

…the ultimate purpose of weather forecast information is to help users make informed decisions, yet much remains to be done to translate

weather forecast information to societal benefits and impacts. To work toward this goal, a closer connection

between meteorological research and societal needs is essential, because problems are not meteorological or societal alone.

This simple notion spread collaboration like a wildfire.

By the time of the BAMS article, some 80 people had become WAS*IS denizens, pursuing projects that fuse meteorological and societal expertise.Demuth et al. took the unusual step of listing every one of these participants and affiliations in their article. There was a method to the rolodex approach: as a grassroots endeavor, WAS*IS was looking to hook up likeminded people–to create a community within a community that would share ideas and identify holes in the knowledge. As anyone who has done interdisciplinary research will tell you, five years ago was still the dark ages for support for integrating social scientists in meteorological work. Acritical mass of demand needed to be created; the hope was that readers would see who was involved and get in touch, fueling more questions and more interdisciplinary projects and more clamoring for changes in funding and attitudes toward research and services.

Already, just five years later, the WAS*IS community numbers some 276 people, many of them just starting out careers, searching for ways to connect the physical sciences with the social sciences, undaunted by the funding landscape they’d inherited.

With no money to give out, the revolution could promise cameraderie. WAS*IS, says AMS Policy Director William Hooke, “was the portal, the gateway, to a transforming experience”:

You’d be encouraged to join other entry-level professionals who had participated in an intense one-week dialog bringing together meteorologists and social scientists, helping them bridge their respective disciplines, network, and start projects that they could (and would, and continue to) build on over years.

Sound good? It was. The couple of hundred people who participated never stop talking about it, sharing their experience and their hopes and aspirations with the likes of you and me. They’ve come from the ranks of weather service forecasters. From broadcast meteorologists. From research scientists. From economics. Psychology. Sociology. They’ve caught the fever.

And they’re still changing our community. They provided part of the interest in and some of the traction and juice behind the NOAA National Weather Service thrust toward a Weather-Ready Nation.

Now for the bump in the road part. Earlier this week Jeff Lazo, director of NCAR’s Societal Impacts Program, sent out disturbing news:

Due to the tough budget times and NOAA’s choices about the allocation of their funds, we regret to say that external funding of the Collaborative Program on the Societal and Economic Benefits of Weather Information (aka the Societal Impacts Program) has been discontinued.

We have thus discontinued or suspended non-research related activities including WAS*IS, the Societal Impacts Discussion Board, the Weather and Society Watch, the Extreme Weather Sourcebook, and other information resources. As such we will be “taking down” these webpages as we will not be able to maintain them.

The Societal Impacts Program Discussion Board will be reinvented very shortly as a community service supported by Rebecca Morss here at NCAR. Please look for a message from her in the next week or so as we hope that a new incarnation of the board comes back online.

Hooke writes that it “is a tremendous loss”, but points out that

Meteorologists and social scientists trying to spin up the Weather-Ready Nation must choose whether to be deflated by this news or soldier on. It won’t be easy. Ironically, the sense of shared community and common purpose fostered by WAS*IS gives all parties a fighting chance to succeed.

Indeed, the Weather Ready Nation concept pushed by NOAA right now could prove to be the break that the revolution was looking for. Now fringe ideas are central to the goals of the entire weather enterprise; people in the halls of government are reaching for insights from neglected fringes. The cause of WAS*IS may have left the streets to be taken up by the establishment itself.

Solar Storms Are Noisy

A doctoral student at the University of Michigan has created a sonic representation of the intense solar storm that erupted in early March. Robert Alexander gathered 90 hours of raw data from two NASA spacecraft–the MESSENGER and the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory. Through isomorphic mapping, he applied that data to an audio waveform. The resulting sound lasted only a fraction of a second, so Alexander used algorithms to extend the playback length. The final soundtrack portrays a cacophony of solar particles emitted by the storm as they slammed into the spacecraft. Listen for yourself in the clip below.

Small Microbes Play Big in Climate Arena

Microbes may be small, but they shouldn’t be ignored when considering global climate. According to a new colloquium report from The American Academy of Microbiology, microbes such as bacteria, algae, and fungi play a powerful role in the Earth’s climate. “Incorporating Microbial Processes into Climate Models” notes how the impact of microbes on the atmosphere goes way back in time. The critical mix of carbon dioxide and oxygen we take for granted as sustaining life on the planet is due to the rise of these tiny creatures eons ago.

So what specifically do these minute forms of life have to do with climate today? According to the report, the answer is plenty. “The sum total of their activity is enormous. But of course not all microbes are the same—some of them are producing oxygen, others are consuming it. Some are taking carbon dioxide out of the air, others are adding it.”

The big questions that the report asks and plans to address by incorporating microbial processes into climate change models: what’s the overall effect of microbial activities on the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere? Is it possible this activity will absorb the carbon dioxide being added to the atmosphere? Or will the rising global temperature might spur microbes to produce even more carbon dioxide?

The authors recognize that the gap between the climatology and microbiology is large, but they say it is not insurmountable. Some of the same technologies used to collect data for climate models—satellite imaging of cloud cover and precipitation, submarine cables that monitor changes in temperature and salinity, sensors to retrieve real-time data from remote locations—can also be applied to measuring biological phenomena. Collaboration between the sciences, they believe, will benefit both fields.

A more detailed look at the report is available here.

Upping the Ante on Modeling Climate Change Impacts

There is a growing urgency to produce global projections of how a warming climate could affect life on Earth.

“Impact research is lagging behind physical climate sciences,” says Pavel Kabat, director of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) in Austria. “Impact models have never been global, and their output is often sketchy. It is a matter of responsibility to society that we do better.”

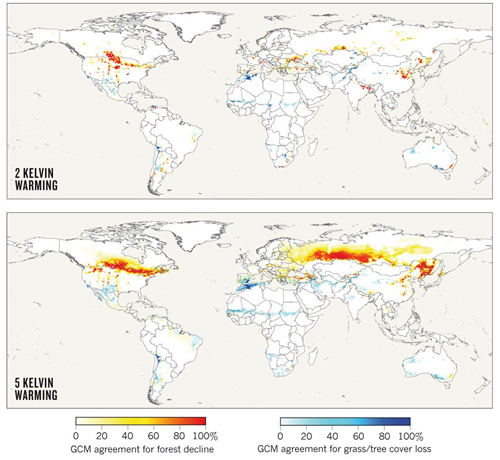

Time is running out for researchers hoping to contribute impact simulations to the IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report (scheduled for publication in 2014). So last month, the IIASA and the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) started a project to compare climate-impact models collected from more than two dozen research groups in eight countries. The Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project (ISI-MIP) will integrate climate data from state-of-the-art models, using a range of greenhouse-gas emission scenarios (models used in the project can be found here). Because the various emissions scenarios result in a range of projected global temperature increases, potential impacts also can vary widely across a range of scenarios. It is hoped that the project will clarify systematic biases that can cause models to produce disparate results.

The models will investigate the effects of climate change on global agriculture, water supplies, vegetation, and health. Results are due by July 1, and reports on each of the four impact areas are scheduled to be completed by January of 2013. This means the data could be available for the IPCC’s next report–which “will make a real difference for the assessment process,” notes Chris Field of the Carnegie Institution for Science, cochair of IPCC Working Group II. “I greatly appreciate the initiative required to get this activity underway, and I appreciate the commitment to fast-track components that will yield results in time for inclusion in the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report.”

The ISI-MIP is scheduled to continue into 2013 and could be expanded to analyze climatic impacts on transport and energy infrastructures.

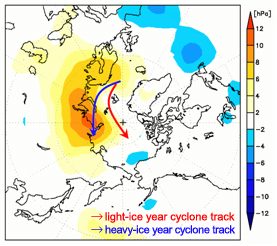

Eurasian Cold Snap a Product of Arctic Warmth

In a paradox that it seems only nature can muster—like quelling a year-long drought in the western two-thirds of Texas with record snows—it turns out that warming going on in the Arctic this winter is the likely culprit behind killer cold and snow that had been plaguing Eastern Europe since late January. And it is now also likely linked to the colder-than-normal winter occurring in Japan and Western Asia.

Weather patterns since the fall have set up in such a way as to leave large expanses of Arctic Ocean, particularly the Barents and Kara Seas north of Scandinavia and Russia, nearly ice-free. In fact, an image from early February posted to the Arctic Sea Ice Blog shows this area north of the Arctic Circle as open water for the first time in what it refers to as the “new Arctic regime (2005-present),” when it should be completely frozen over.

The changing weather patterns resulting from this new era of record sea ice melt seem to have helped build up a huge helping of frigid air over Siberia that came crashing southward as soon as the storm track shifted, which it inevitably does throughout the year. Instead of Western Europe like the last two winters, this time the bitter cold targeted Eastern Europe, delivering snow-laden storms to nations of the Eastern Mediterranean and even North Africa, as well as far Western Asia, Korea, and Japan.

Numerous researchers have been working the last few years to figure out what’s going on. The environmental news and technology site Bits of Science wrote a timely online article explaining the findings of recent published research and then tying the studies to the different teleconnections patterns that influence Eurasia’s winter weather — the Arctic Oscillation and its focused cousin, the North Atlantic Oscillation. Together, these pressure anomaly-driven climate patterns can dictate where winter’s worst cold and snow and best warmth become established.

A new study headed for publication in the Journal of Climate in March further extends the influence of the warming Arctic. The article by the Research Institute for Global Change’s Jun Inoue et al. contends that the storm track over the Barents and Lara Seas takes a more northerly route when sea ice there is reduced. In a positive feedback mechanism, the northward-shifted storm track pulls warm air over the Arctic Ocean. At the same time, cold air builds over Siberia and the Norwegian coast, and becomes poised to spill southward, or to the west and the east.

“Such warm Arctic and cold continental conditions are referred to as a warm-Arctic cold-Siberian (WACS) anomaly, and the WACS anomaly could be a procurer of severe weather in the downstream region,” the authors report.

As with the collective research on the warming Arctic’s influence on mid-latitude winter weather, Inoue et al. conclude that using sea-ice variability from this region of the Arctic would improve the reliability of the seasonal weather predictions in individual years.

How does it feel?

Sunday was supposed to be National Weatherperson’s Day. Did you receive flowers? Did distant relatives call to congratulate you? Did adoring fans of your forecasts voice their support?

Or did the much anticipated holiday pass uneventfully while everybody was preoccupied by lesser events…oh, like the Super Bowl, for instance? Just a case of bad scheduling conflicts, or a conscious attempt to diss you?

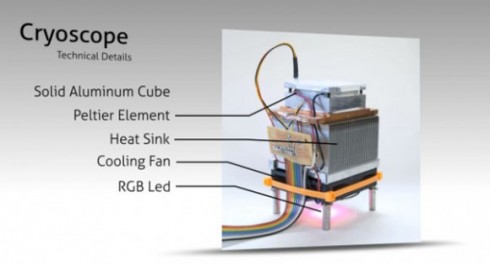

If you’re a meteorologist, especially a forecaster, you know how it feels to be underappreciated, to be told you’re not right often enough, that your job is going to be taken by a computer. Not only might you get ignored on the very day meant for you, now you get replaced…by a cube:

Hook the device to your smart phone weather app and it adjusts its temperature to match the forecast temperature. So that’s how the weather feels! And how does it feel to be replaced by an aluminum box with a heating element and simple sink inside it?

Bob Dylan stuck the knife in with “You Don’t Need a Weatherman to Know Which Way the Wind Blows,” but he twisted it cruelly with:

How does it feel

How does it feel

To be on your own

With no direction home

Like a complete unknown

Like a rolling stone.

A forecaster’s fate? We think not.

Clearly this invention leaves much to be desired. In addition to being unable to prognosticate without a web app, after a decade or more of good minds trying to develop better ways of conveying uncertainty information in weather forecasts in a few words or pictures, here comes a giant deterministic step backward for communicating tomorrow’s conditions. And of course, although inventor Robb Godshaw of Rochester Institute of Technology insists that the Cryoscope compensates for the difference between conducting heat with aluminum versus air (and also effects of wind chill), it is difficult to imagine equating the touch of the hand to how it feels to move and breathe in the atmosphere. No, this box is not how it feels at all.

In fact, there’s a lesson here. Much as it is difficult to teach any scientific concept to a wide audience, let’s keep in mind that over the years people have developed an uncanny sense of how they feel, personally, when it’s 40, or 50, or 60 degrees Fahrenheit and so on (not to mention wiser folks who’ve learned all this in terms of Celsius). In fact, people probably have a much more acute ability to imagine what a 10 degree rise in temperature will feel like than what carrying a 10 pound increase in load will feel like.

The depth to which the temperature scale is ingrained with exquisite sensitivity into our consciousness is summed up by a viewer’s comment on the Cryoscope promo video page:

The step after that would be to hook up a water hose to it to tell you when it is rainy.

Avid Surfer, Forecaster Receives Joanne Simpson Award for Sustained Mentorship of Colleagues

Mark Willis, a development manager and forecast strategist for Surfline—the go-to global surfing forecast company—is the 2012, and first, recipient of The Joanne Simpson Mentorship Award. Willis, a lifelong surfer who is at home when the surf is cranking, won the award for aiding NWS volunteer interns in gaining experience valuable to their future careers through dedicated mentorship, and sustained encouragement and guidance.

The Front Page set out to learn more about Willis and his penchant for mentoring. He worked for Surfline for several years in the late 1990s and early 2000s before joining the NWS Eastern Region marine program. Then, recently, he returned to Surfline. The following is our Q and A session in which Willis sheds some light on his particular style of engagement with colleagues.

What’s your area of expertise in meteorology? And did that help you secure the most recent position you had with NOAA?

My expertise is in marine and coastal forecasting, but I enjoy all aspects of meteorology and oceanography. My marine background definitely helped me secure my last position at NOAA as the Marine Program Manager at NWS Eastern Region Headquarters.

What was your passion that got you into marine forecasting?

I became interested in marine forecasting through surfing. I grew up surfing on the East Coast and became fascinated by waves and how they changed so quickly. I learned much of the science behind wave forecasting on my own and by working at Surfline as its difficult to get much formal training on the subject. I became involved in ocean wave modeling in graduate school and continued to work on wave modeling projects in the NWS. I’ve been lucky to be able to work in forecast offices that have marine responsibility as this has greatly enhanced my knowledge of the ocean and the atmosphere.

What is your current title and affiliation, and what is it you now do?

Global Forecast Development Manager/Lead Forecast Strategist with Surfline, Inc. Surfline also owns Buoyweather.com and Beachlive.com. My job is to lead Surfline/Buoyweather/Beachlive’s push into international markets and also help to fine tune existing products and develop future products.

Who were the folks you were mentoring?

I have mentored several students and employees throughout my career as a meteorologist. I mentored volunteer interns when I was a forecaster at the NWS forecast office in Newport/Morehead City, North Carolina. Most were college students but I also worked with a couple of high school students. I also mentored new employees when I was the East Coast forecast manager at Surfline in the early 2000s. I have been fortunate that both of my employers have allowed me to mentor, as it’s something I greatly enjoy.

Tell us your philosophy on mentoring and what sets it apart from others’ techniques/methods?

One thing I always thought of when I was working with students and/or new hires was that I was in their shoes not too long ago. I always ask myself, “What would have made me grow and feel more comfortable?” The answer to that was always the same – just make sure they feel welcome, included during forecast decisions, and find the right times to train and teach. I think it’s important not to continuously throw things like QG theory down their throats and show them how much you know. It’s more important to get to know the person, find their learning style, and adapt to the human being. Most of all, get to know who they really are, ask about their family, hobbies, find their true interests in meteorology and just try to educate and mentor where you can.

As far as what sets that apart from others’ techniques/methods – I’m honestly not sure. I did take the student that nominated me for this out surfing a couple of times though where we talked about life and exchanged waves, so maybe that’s what set it apart!

How do you use that to promote excellence in forecasting/the atmospheric sciences?

I just try to be a hard worker, lead by example, and follow my passions. Hopefully that promotes excellence in our ever so humbling field.

Will you continue to mentor in your new position?

Every chance I get. I also hope I get the opportunity to be mentored by some of the veterans at Surfline as well, as they have an incredible staff with the best group of marine/surf forecasters and modelers in the world. Surfline is always looking for the brightest and the best so hopefully I’ll get the opportunity to mentor new employees in the future.

When you first learned you were going to receive this particular award, what was your reaction?

I was shocked when Jon [Malay] called me to tell me the news, honestly. This award is hands down one of the highlights of my career. I have a great sense of pride in the fact that the students and colleagues I mentored went out of their way to nominate me for this.

One additional thing I’d like to highlight on this subject is that the news of the award came right after a very stressful period of dealing with Hurricane Irene both professionally and personally. The award definitely lifted my spirits after that!

What advice would you give a colleague who wanted to win this same award next year?

Be yourself, get to know the people you are mentoring, and find good entry points to train and mentor. Don’t force it.

What single piece of wisdom would you hope those you mentored would carry into their careers?

As the late Sean Collins (founder of Surfline) taught me and inscribed into the Surfers’ Hall of Fame—“Follow your Passions.” You’ll perform much better and find more satisfaction in your career if you enjoy what you are doing.

The Eyes of Texas Are on Steer-ing Level Winds

Jill Hasling, CCM, president of The Weather Research Center in Houston, kindly sent us confirmation of the latest forecast on this Groundhog Day. In front of 200 kids at the John C. Freeman Weather Museum,

Alamo, the Texas Longhorn, did not see his shadow so Texas should have an early spring. Texas is too big for a groundhog to predict its weather.

- Maureen Maiuri, executive director of The John C. Freeman Weather Museum, and Jill Hasling make a long-range forecast by drawing a bullseye on the 500 mb level winds, bypassing the usual Groundhog Day method of digging into the surface data..

Hazardous Weather Testbed Team Wins 2012 Spengler Award for Severe Storm Collaboration

The 2012 Kenneth C. Spengler Award recipient is a team of eight scientists and forecasters with the NOAA Hazardous Weather Testbed (HWT). Their collaborative efforts are being acknowledged for bringing the government, academic, and private sectors together in a visionary, proactive, and exemplary manner to deal with the challenges posed by hazardous weather.

The HWT, a facility jointly managed by NSSL, the Storm Prediction Center (SPC), and the NWS Oklahoma City/Norman Weather Forecast Office (OUN), is leading the way to engage the weather enterprise in turning severe storm research into operations.

HWT team members are John “Jack” Kain, Steve Weiss, Russell Schneider, Mike Coniglio, Greg Carbon, David Bright, Jason Levit, and Jay Liang. The Front Page met with Schneider (SPC director) and Weiss (SPC chief of support) to learn more about HWT, its dual programs focused on warnings and forecasts, and the advances HWT has championed as well as the challenges that remain.

The full interview is available below.