by Tanja Fransen, AMS Councilor and Mentoring Program Ad-Hoc Committee Chair

AMS has a wealth of talent and we’d love to see more of our members signed up for the Mentoring 365 program as mentees, mentors–maybe both! We should never stop learning. When I started in college and early in my career, I hadn’t even heard of the term mentor, let alone thought of myself as a mentee. Looking back now, there are so many people who I can count as someone who had a positive influence in my decisions and the path my career took. Coaches, mentors, professors, classmates, co-workers, bosses, supervisors, leaders: they all had a hand in shaping my career because they invested their time in me. Who are you investing your time in? Who is investing their time in you?

About ten years ago, through various leadership programs, I learned more about formal mentoring, and I couldn’t help but wonder, “Why doesn’t everyone have a mentor?” It’s a logical step for anyone who is excited about their careers and looking for guidance. Everyone can benefit from having a non-coworker or non-supervisor to talk with, who will be honest with them, encourage them, celebrate their successes, and help them get to the next levels in their careers. I’ve participated in several formalized programs, and it always puts a smile on my face to see these mentees doing well. One of the most amazing moments for me was having a mentee whose son was murdered while we were working together. We went from my mentoring someone in sciences and government, to learning one of the most amazing lessons about grace and forgiveness, and I’ll never forget that experience. Not all benefits are apparent when you start a program!

When I was nominated to run for the council of the AMS, it was an obvious niche that was needed. I made it one of my priorities to bring a formal program to all of our AMS members. With the help of others within AMS who also had our people as their passion, including Matt Parker, Keith Seitter, Wendy Marie Thomas, Wendy Abshire, Maureen McCann, and Donna Charlevoix, we were able to connect AMS with the American Geophysical Union’s (AGU) Mentoring365 program through a signed MOU. AMS members can join this program as either a mentee, a mentor or both. You also have access to mentors across the geophysical sciences, including members of the AGU, the Society of Exploration Geophysicists (SEG), Association for Women Geoscientists (AWG), and the Incorporated Research Institutions for Seismology (IRIS).

I’ve met the most amazing people thanks to AMS, from the enthusiastic students, to the eager early career professionals to the mid- and late-career professionals who have the most amazing resumes and curricula vitae! Let’s tap into all of that energy out there and build Mentoring 365 for the benefit of all! Join today!

Jeff

Jeff

It Used to Be "Inadvertent Climate Modification," Too

AMS Executive Director Keith Seitter sent a letter today to President Trump. It begins,

In an interview with Piers Morgan on Britain’s ITV News that aired Sunday, 28 January, you stated, among other comments:

“There is a cooling, and there’s a heating. I mean, look, it used to not be climate change, it used to be global warming. That wasn’t working too well because it was getting too cold all over the place”

Unfortunately, these and other climate-related comments in the interview are not consistent with scientific observations from around the globe, nor with scientific conclusions based on these observations. U.S Executive Branch agencies such as NASA and NOAA have been central to developing these observations and assessing their implications. This climate information provides a robust starting point for meaningful discussion of important policy issues employing the best available knowledge and understanding.

Read the whole letter here.

In response to the BBC interview, Bob Henson of Weather Underground’s Category 6 blog gave a detailed debunking of the President’s comments. It’s a useful read for those wanting to parse out the persisting misunderstandings about the climate change discourse.

One misconception Henson clarifies is the talking point about which came first, “climate change” or “global warming.”

The history of the phrases “climate change” and “global warming” is much more interesting than Trump gives it credit for. Researchers were using climatic change or climate change as far back as the early 20th century when writing about events such as ice ages. Both terms can describe past, present, or future shifts—both natural and human-produced—on global, regional, or local scales.

Climate change is a general term that has applied over the years to many forms of climate change. Per the AMS Glossary:

Any systematic change in the long-term statistics of climate elements (such as temperature, pressure, or winds) sustained over several decades or longer.

It applies to both natural and human-caused changes (and “anthropogenic climate change” gets its own Glossary entry).

Obviously, the term still applies. So does “global warming.” In 2018 already, “global warming” is in the title of several scientific papers accepted to AMS journals.

Henson traces the first usage of “global warming”—a term specific to the observed climate trend—to a paper by Wallace Broecker in the 8 August 1975 issue of Science.

This may indeed be the first paper to apply “global warming” to a changed worldwide condition, via carbon dioxide release. Broecker was writing in anticipation of this trend becoming an observed fact, surpassing the then-prominent cooling influence of dust and pollutants as

the exponential rise in the atmospheric carbon dioxide content will tend to become a significant factor and by early in the next century will have driven the mean planetary temperature beyond the limits experienced during the last 1000 years

The idea that the Earth would warm as a whole, if not in every locale or region, was not new at the time of Broecker’s paper. In 1971, the National Academy of Sciences had included an objective to study the “effect of increasing carbon dioxide on surface temperatures” in its report, “The Atmospheric Sciences and Man’s Needs” (summed up by Robert Fleagle in BAMS that year).

The term “global warming” itself appears in AMS journals at least five years before Broecker’s paper. Jacques Dettwiller addressed the means of collecting long term global temperature records in the February 1970 Journal of Applied Meteorology. Lamenting the difficulty of separating out urban heat island effects, Dettwiller advocated monitoring deep soil temperatures, which seemed to “afford a means to monitor the global increase in temperature during the first half of the 20th century.”

For our purposes, it’s a landmark paper in the way Dettwiller cited a 1964 paper in Monthly Weather Review by Stanley Changnon that used such techniques in rural Urbana, Illinois: Changnon, wrote Dettwiller, “was able to discern values for global warming….”

At the time, the “current” term for global warming or anthropogenic climate change through the greenhouse effect was actually, ”Inadvertent Climate Modification.” That was the title of a 1971 report by an international group of climatologists convened by MIT and the Royal Swedish Academies for a “Study of Man’s Impact on Climate.” It was one of the first large consensus reports to warn of sea level rise, polar ice cap melt, major Arctic warming, and more.

After nearly a half century of highly prominent scientific warnings, a word was indeed dropped from the climate lexicon because it no longer made sense. That word was “inadvertent.”

Pathways from Meteorology–Political, Commercial, Personal

The path from good science to good societal decisions is the central paradigm not only of the scientist’s perspective on how to impact the world, but also to the public’s faith in science itself. It also turns out to be a path of personal growth as well.

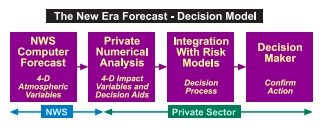

There’s a whole genre of attempts to depict these connections between science and its usage. One noteworthy example of such diagrams was published by the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society back in 2002. John Dutton (now of Prescient Weather, Ltd.; then dean at Penn State University), saw a need to update the flow of scientific information from numerical models to decision makers. He recognized the increased use of computerized decision models that were interpreting scientific forecast input; he also wrote eloquently about the feedback and blurring between economic sectors, users, and scientists. Here’s what he came up with:

While Dutton’s focus was on expanding economic opportunity, he wrote with a palpable sense of inexorably widening horizons from that kernel of numerical weather modeling into all corners of societal activity: “Wider distribution leads to enhanced creativity and advancing capability as a thousand flowers bloom,” Dutton wrote.

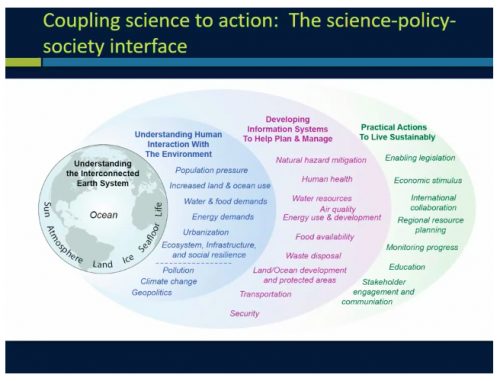

That same vision of the expansive horizons, all stemming from a mere act of meteorology, infused Susan Avery’s address to the AMS Student Conference in Austin this year. Only in this case, it is a parallel to Dutton’s economic view–a rippling from science to policy to society. In her talk, titled “Usable Science: Connecting Science to Action,” Avery, president emerita of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, depicted the pathway from science to society as a personal journey. Her ever-widening ellipses show an expansion of opportunities, knowledge, and horizons throughout a career as you move beyond the possibilities of a scientific education.

She explains:

Often those pathways, those learning opportunities, those experiences come about by the sciences themselves, and the evolution of the science. Believe it or not, the demands right now for you and predictive information—it’s not just about the weather forecast anymore.

I know this is the American Meteorological Society and everybody thinks it’s all about weather, but this Society itself, which has been an inspirational part of my personal and my professional growth, it also isn’t just about the weather anymore and the daily weather forecast.

I’d like you to think broadly as you go through your life and your career. Some of these learning experiences you might have will allow you to evolve your thinking in terms of what is knowledge of the atmosphere and how does it apply to something else other than the daily forecast.

Part of this idea of coupling science to use is associated with understanding the interdependency of what you’re trying to do and what you’re trying to solve. I like this diagram because—it looks kind of complicated—but it’s really the only one I can think of in trying to understand what is this connection between science, policy, society, and use.

First of all, the atmosphere is only one part of our planetary system. A lot of the atmospheric motions there are because of ocean-atmosphere interaction. You have to understand there’s an ocean driver there as well. When you worry about how that plays out in terms of people, you have to worry about where we live, on the land….A lot of atmospheric science departments today are really Earth system science departments. The science is pushing us that way.

If you want to apply that science to solving problems, it’s pretty important to understand what those problems are and the interdependencies particularly between the planet system and humans. So that second ellipse talks about those interdependencies—particularly population pressure, societal desires, and what that means in terms of consumption patterns, water use, energy use, where you live. We are a human forcing function on that planetary systems.

And so to the third ellipse and on to the last as the knowledge pushes us. Dr. Avery explained, “These are just some of the pathways that you might see yourself taking in the future.”

You now can hear Avery’s whole talk online.

Is It Just Us…or Was That the BBQ Talking?

So many conversations at the 2018 AMS Annual Meeting started–and ended–on the same note, and Dakota Smith captures it just right in his “Weather Nerds Assemble” vlog:

Communication is a huge aspect in this field….If a forecast is a hundred percent accurate, but no one understands it, it’s not a useful forecast. That in a nutshell was what this meeting was about.

According to Smith, all that geeked out conversation amongst 4,200 weather, water, and climate nerds added up to at least these four lessons:

- The future is bright: “I talked with so many intelligent, bright, passionate students who are bound to make an impact on our community. Keep up the grind!”

- Meteorologists are incredibly strong: The communications workshop reflecting on the experience of Harvey, Irma, and Maria showed that “meteorologists across the country used…love and passion to fuel them through this relentless hurricane season.”

- Austin has incredible BBQ.

- Meteorologists are awesome. “I already knew this before…we love weather, and we love science!”

The last two are obvious, right? The first two make our day. Share your own take-away points; meanwhile, you owe yourself the injection of enthusiasm–just in case you got lost in the trees since returning home:

A Letter from AMS President Roger Wakimoto

Dear AMS Community,

I am delighted to send this letter to you after the wonderful Annual Meeting in Austin. You told us that the Presidential Forum with Richard Alley and the Presidential Town Hall on the recent hurricane season were the highlights of the week (both can be viewed online) and I am glad that our efforts to arrange for these two events were well-received. The latter was possible owing to our breadth as a scientific and professional society. It allowed us to assemble a panel of experts from the university and broadcast communities, NWS, FEMA, and Flood Control District that could tell a story that was quite engaging.

I was honored to have completed President Matt Parker’s vision for the Annual Meeting. I believe that he would have been very pleased with the program. Of course, the AMS staff, Executive Committee, and Council are an amazing and supportive group to work with and I owe them a deep debt of gratitude for supporting me during the past year.

I wanted to take this opportunity to highlight a couple of priorities that I will be working on in the coming months. I am deeply committed to diversity, equity, and inclusion. The AMS supports a number of programs that illustrate their commitment to diversity. However, I believe it is time to step back and review diversity, equity, and inclusion across AMS in a holistic manner and assess the collective effectiveness of its broadening participation efforts. What is our strategic vision on this important topic? With the support from Council, I appointed and charged a task force to review what the Society has accomplished to date in this area and to deliver a set of recommendations, including bold ones if necessary, to guide us as we rapidly approach our Centennial celebration. Susan Avery has kindly agreed to Chair this task force and I hope you contact her with your advice and suggestions.

There have been a number of events across the nation this past year that few of us could have predicted. The withdrawal from the Paris Climate Agreement (currently the only nation to do so), the March for Science, a proposed tax on graduate student tuition waivers, controversy at the EPA on the subject of membership on advisory committees and climate-related issues, and no Science Advisor for the Administration (the longest time this position has been left unfilled since it was created). These and other events beg the question whether AMS should alter the direction of its advocacy program or stay the course in this age of disruption. I have asked the Council to discuss this topic in the coming months so that we can define a path forward and communicate it clearly to all of you.

Finally, I would like to remind you of my vision for next year’s theme for the 2019 Annual Meeting in Phoenix, “Understanding and Building Resilience to Extreme Events by Being Interdisciplinary, International, and Inclusive.” It is the first time that extreme events, international and inclusive have been specifically highlighted in a theme and it is a timely subject owing to the natural disasters that impact our society and the need to build resilience. Xubin Zeng and Wen-Chau Lee are the overall program co-chairs and they are working with a great team that includes Julie Demuth, Rebecca Haacker-Santos, Sarah Jones, and Chris Schultz. The 2019 Annual Meeting will be the kickoff for a year-long celebration leading up the 2020 Centennial Meeting in Boston (will it snow or not??).

AMS has been a great organization that has supported me personally throughout my long scientific and professional career. In the bigger picture, AMS has endeavored to remain relevant and has adapted to change when necessary. Of course, AMS only exists because of you and the enormous number of hours that you volunteer to the organization. It is the primary reason that I know that the Society will continue to be strong and impactful for years to come. I hope to both meet and interact with as many of you as possible this year.

Roger M. Wakimoto, President, American Meteorological Society

With Floods or Baseball, It's a Game of Percentages

Perhaps no one thought that Game 5 of the World Series would end the way it did. It started with two of the game’s best pitchers facing off; a low-scoring duel seemed likely. But the hitters gained the upper hand. In the extra-inning slugfest the score climbed to 13-12.

If you started that game thinking every at-bat was a potential strike-out, and ended the game thinking every at-bat was a potential home run, then you’ll understand the findings about human expectations demonstrated in a new study in the AMS journal, Weather, Climate and Society. University of Washington researchers Margaret Grounds, Jared LeClerc, and Susan Joslyn shed light on the way our shifting expectations of flood frequency are based on recent events.

There are two common ways to quantify the likelihood of flooding. One is to give a “return period,” which tells (usually in years) how often a flood (or a greater magnitude flood) occurs in the historical record. It is an “average recurrence interval,” not a consistent pattern. The University of Washington authors note that a return period “almost invites this misinterpretation.” Too many people believe a 10-year return period means flooding happens on schedule, every 10 years, or that in every 10-year period, there will be one flood that meets or exceeds that water level.

Grounds et al. write:

This misinterpretation may create what we refer to as a ‘‘flood is due’’ effect. People may think that floods are more likely if a flood has not occurred in a span of time approaching the return period. Conversely, if a flood of that magnitude has just occurred, people may think the likelihood of another similar flood is less than what is intended by the expression.

In reality, floods that great can happen more frequently, or less frequently, over a short set of return periods. But in the long haul, the average time between floods of that magnitude or greater will be 10 years.

One might think the second common method of communicating about floods corrects for this problem. That is to give something like a batting average–a statistical probability that a flood exceeding a named threshold will occur in any given time period (usually a year). Based on the same numbers as a return period, this statistic helps convey the idea that, in any given year, a flood “might” occur. A 100-year return period would look like a 1% chance of a flood in any given year.

Grounds and her colleagues, however, found that people have variable expectations due to recent experience, despite the numbers. The “flood is due” effect is remarkably resilient.

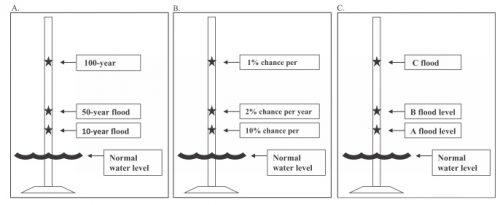

The researchers surveyed 243 college students. Each student was shown just one of the three panels below of flood information for a hypothetical creek in the American West:

Each panel showed a different method of labeling flooding (panel A showed return periods; panel B percent chance of flooding; panel C had no quantification, marking levels A-B-C). The group for each panel was further subdivided into two subgroups: one subgroup was told a flood at the 10-year (or 10% or “A”) marker had occurred last year; the other subgroup was told such a flood last occurred 10 years ago. This fact affected the students’ assessment of the relative likelihood of another flood soon (they marked these assessments proportionally, on an unlabeled number line, which the researchers translated into probabilities).

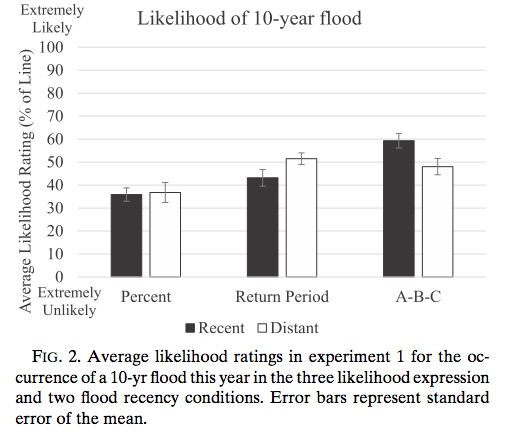

Notice, the group on the right, who did not deal with quantified risks (merely A-B-C), assessed a higher imminent threat if a flood had occurred last year. This “persistence” effect is as if a home run last inning made another home run seem more likely this inning. The opposite, “flood due” effect, appeared as expected for the group evaluating return period statistics. Participants dealing with percentage chances of floods were least prone to either effect.

This test gave participants a visualization, and also did not quantify water levels. Researchers realized both conditions might have thrown them a curve ball, skewing results, so the researchers tried another survey with 803 people (gathered through Amazon.com) to control test conditions. The same pattern emerged: an even bigger flood-is-due effect in the group evaluating return-period, a bigger persistence effect in the group with unquantified risks, and neither bias in the group assessing percentage risks.

In general, that A-B-C (“unquantified”) group again showed the highest estimation of flood risk. The group with percentage risk information showed the least overestimation of risk, but still tended to exaggerate this risk on the scales they marked.

Throughout the tests, the researchers had subjects rank their concern for the hypothetical flood-prone residents because flood communication stops not at understanding, but at concern that motivates a response. Grounds et al. conclude:

Although percent chance is often thought to be a confusing form of likelihood expression…the evidence reported here suggests that this format conveys the intended likelihood information, without a significant loss in concern, better than the return period or omitting likelihood information altogether.

How concerned these participants felt watching the flood of hits in the World Series…well, that depended on which team they were rooting for.

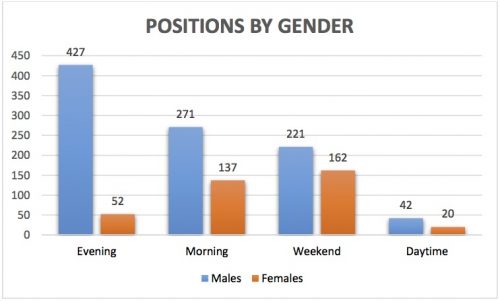

Persisting Gender Gap for Weathercasters

While the ranks of women weathercasters are growing slowly, they continue to lag behind their male colleagues in job responsibilities.

A new study to be published in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society shows that 29% of weathercasters in the 210 U.S. television markets are female. This percentage has roughly doubled since the 1980s.

Despite this progress, only 8% of chief meteorologists are female. Meanwhile, 44% of the women work weekends while 37% work mornings. Only 14% of the women work the widely viewed evening shifts.

Last year, 11% of evening or primetime weathercasters were female. That’s only about one-third the percentage reported in a study published in 2008, suggesting a possible decline in female representation in this high-profile broadcast slot.

Educational levels were gender dependent, as well. While 52% of the women had meteorology degrees, 59% of the men did.

Alexandra Cranford of WWL-TV in Slidell, Louisiana, the author of the new study, gathered her data in 2016 from TV station websites. The biographical information was compiled for 2,040 weathercasters, making the study the largest of its kind. Because it relied on self-reported, publicly available information, Cranford suggests that there may be some underrepresentation of various factors: online bios tend might tend to omit information that makes broadcasters look less qualified or experienced. The bios on males were somewhat less likely to omit their exact position at the a station, while the bios on females were somewhat less likely to omit education information.

Previous studies have shown that viewers tend to perceive men as more credible and thus more suited for a variety of broadcast roles, from serious news situations to commercial voice-overs. This perception was one of the motivations for Cranford’s study and may be weighing on hiring and assignment practices for weathercasters. In the article, Cranford notes that past research had indicated,

Constructs including the “weather girl” stereotype and gender-based differences in perceived credibility could potentially contribute to the percentage of women in broadcast meteorology remaining low, especially in chief and evening positions.

Based on the new data, Cranford concludes,

Additional research should explore if factors such as persistent sexism in hiring practices or women’s personal choices could explain why fewer female weathercasters have degrees and why women work weekend shifts while remaining underrepresented in chief meteorologist and evening positions.

Building AMS Community, Maximizing Value of Our Information

by Douglas Hilderbrand, Chair, AMS Board on Enterprise Communication

Early August seems forever ago. Hurricanes Maria, Irma, and Harvey were only faint ripples in the atmosphere. The nation was getting increasingly excited for the solar eclipse of 2017; the biggest weather question was where clear skies were expected later in the month.

During this brief period of calm in an otherwise highly impactful weather year, leaders and future leaders from the Weather, Water, and Climate Enterprise gathered together at the AMS Summer Community Meeting in Madison, Wisconsin, to better understand how “The Enterprise” could work in more meaningful, collaborative ways to best serve communities across the country and the world. Consisting of government, industry, and the academic sector, the Enterprise plays a vital role in protecting lives, minimizing impacts from extreme events, and enhancing the American economy.

The AMS Summer Community Meeting is a unique time when the three sectors learn more about each other, about physical and social science advances, and discuss collaboration opportunities. Strengthening relationships across the Enterprise results in collaborations on joint efforts, coordination in ways that improve communication and consistency in message, and discussion of issues on which those in the room may not always see eye-to-eye. Every summer, one theme always rises to the top — the three sectors that make up the Weather, Water, and Climate Enterprise are stronger when working together vs. “everyone for themselves.”

This “true-ism” becomes most evident during extreme events, such as the trifecta of devastating hurricanes to impact communities from Texas to Florida to Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. The AMS Summer Community Meeting (full program and recorded presentations now available) featured experts on weather satellites, radar-based observations, applications that bring together various datasets, communications, and even the science behind decision making. As Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria formed, strengthened, and tracked toward land, relevant topics discussed at the Summer Community Meeting were applied under the most urgent of circumstances. GOES-16 images, though currently “preliminary and non-operational,” delivered jaw-dropping imagery and critical information to forecasters. As Harvey’s predicted rainfall totals created a dire flooding threat, the entire Enterprise rallied together to set the expectation that the flooding in eastern Texas and southwestern Louisiana would be “catastrophic and life threatening.” This consistency and forceful messaging likely saved countless lives — partially due to the Enterprise coming together a month before Harvey to stress the importance of consistency in messaging during extreme events.

If you are unfamiliar with the AMS Summer Community Meeting, and are interested in participating in the summer of 2018, take some time and click on the recorded presentations over the past few years (2017, 2016, 2015). In 2016, the Enterprise met in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, home of NOAA’s National Water Center, and discussed recent advances in water forecasting and the launch of the National Water Model. A year earlier, in Raleigh, NC, future advances across the entire end-to-end warning paradigm were discussed.

We don’t know when or what the next big challenge will be for the Weather, Water, and Climate Enterprise, but a few things are certain… The state of our science — both physical and social — will be tested. Communities will be counting on us to help keep them safe. And to maximize the value chain across the Weather, Water, and Climate Enterprise, we will need government, industry, and academia continuing to work together and rely on each other. These certainties aren’t going away and provide the impetus for you to consider participating in future AMS Summer Community Meetings.

Peer Review Week 2017: 4. Shifting Demands of Integrity

For Journal of Hydrometeorology Chief Editor Christa Peters-Lidard, peer review upholds essential standards for a journal. “Maintaining that integrity is very important to me,” she said during an interview at the AMS Publications Commission meeting in Boston, in May. Historically, the burden of integrity has fallen on editors as much as authors and reviewers.

The peer review process we follow at the AMS is an anonymous process. Authors do not know who their reviewers are. So it’s really up to us, as the editors and chief editors, to ensure that the authors have a fair opportunity to not only get reviews that are constructive and not attacking them personally, but also by people that are recognized experts in the field.

Even when reviewers are not experts, “they know enough about it to ask the right questions, and that leads the author to write the arguments and discussion in a way that, in the end, can have more impact because more people can understand it.”

Anonymity has its advantages for upholding integrity, especially in relatively small field, like hydrometeorology. Peters-Lidard pointed anonymity helps reviewers state viewpoints honestly and helps authors receive those comments as constructive, rather than personal.

“In my experience there have been almost uniformly constructive reviews,” Peters-Lidard says, and that means papers improve during peer review. “Knowing who the authors are, we know what their focus has been, where their blind spots might be, and how we can lead them to recognize the full scope of the processes that might be involved in whatever they’re studying. Ultimately that context helps the reviewer in making the right types of suggestions.

But the need for integrity is subtly shifting its burden onto authors more and more heavily. Peters-Lidard spoke about the trend in science towards an end-to-end transparency in how conclusions were reached. She sees this movement in climate assessment work, for example, where the policy implications are clear. Other peer reviewed research developing this way.

We’re moving the direction where ultimately you have a repository of code that you deliver with the article….Part of that also relates to a data issue. In the geosciences we speak of ‘provenance,’ where we know not only the source of the data—you know, the satellite or the sensor—but we know which version of the processing was applied, when it was downloaded, and how it was averaged or processed. It’s back to that reproducibility idea a little bit but also there are questions about the statistical methods….We’re moving in this direction but we’re not there yet.

Hear the full interview:

Peer Review Week 2017: 3. Transparency Is Reproducibility

David Kristovich, chief editor of the Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology, explains how AMS peer review process, as a somewhat private process, ultimately produces the necessary transparency.

Peer review is an unpublished exchange between authors, editors and reviewers. It is meant to assure quality in a journal. At the same time, Kristovich noted that peer review is not just something readers are trusting, blindly. Rather, the peer review process is meant to lead to a more fundamental transparency—namely, it leads to papers that reveal enough to be reproducible.

“Transparency focuses on the way we tend to approach our science,” Kristovich said during an interview at the AMS Publications Commission meeting in Boston in May. “If someone can repeat all of the steps you took in conducting a study, they should come up with the same answer.”

“The most important part of a paper is to clearly define how you did all the important steps. Why did I choose this method? Why didn’t I do this, instead?”

Transparency also is enhanced by revealing information about potential biases, assumptions, and possible errors. This raises fundamental questions about the limits of information one can include in a paper, to cover every aspect of a research project.

“Studies often take years to complete,” Kristovich pointed out. “Realistically, can you put in every step, everything you were thinking about, every day of the study? The answer is, no you can’t. So a big part of the decision process is, ‘What is relevant to the conclusions I ended up with?’”

The transparency of scientific publishing then depends on peer review to uphold this standard, while recognizing that the process of science itself is inherently opaque to the researchers themselves, while they’re doing their work.

“The difference between scientific research and development of a product, or doing a homework assignment—thinking about my kids—is that you don’t know what the real answer is,” Kristovich said. Science “changes your thinking as you move along, so at each step you’re learning what steps you should be taking.”

You can hear the entire interview here.