By AMS President Anjuli S. Bamzai

I grew up in a family that valued intellectual pursuits, discipline, and the importance of women’s education—and was provided the support to make sure I received that education despite external social and cultural barriers. In the 1930s, when my mother was young, such values were uncommon outside of her family. My mother was the first woman in our community in the town of Srinagar, Kashmir, to receive a college degree, back in the late 1930s. She was followed by her younger sisters, one of whom went on to become the principal of the women’s college in town. Thus, I grew up with the important privilege of having strong women as role models.

As I entered the atmospheric sciences, one of the women who embodied the undaunted courage and determination in that generation of path-breakers was Dr. Joanne Simpson, the first U.S. woman to obtain a doctorate in meteorology, which she earned from the University of Chicago in 1949. In 1989 she became the first female president of the AMS. She researched hot towers and hurricanes, and was the project lead of the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) at NASA. While I never got a chance to meet Dr. Simpson, she was a beacon of inspiration.

I worked at the National Science Foundation under Dr. Rita Colwell—NSF’s first female director. An eminent biologist, she is recognized for her groundbreaking work on global infectious diseases such as cholera and their connection to climate. At an NSF holiday party during her directorship, I was astounded and inspired by the number of awards and honorary degrees on her office wall, from institutions all over the world! I admire her efforts in developing programs that support the advancement of women in academic science and engineering careers, such as NSF ADVANCE.

This Women’s History Month, as I reflect about women pioneers who inspired me, I thought I’d share with you a few important figures from my mother’s generation and before. Their contributions have indeed made our field a richer place.

June Bacon-Bercey (1928–2019)

When June Bacon-Bercey went to UCLA, her adviser told her she should consider studying home economics, not atmospheric science. Considering that she’d transferred to UCLA specifically for its meteorology degree program, she didn’t believe this was good advice. We’re all lucky she followed her heart.

Bacon-Bercey graduated from UCLA in 1954, the first African American woman to obtain a bachelor’s degree in meteorology there, and early in her career worked for what is now the National Weather Service as an analyst and forecaster. Later, as a senior advisor to the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, she helped us understand nuclear fallout and how atomic and hydrogen bombs affected the atmosphere.

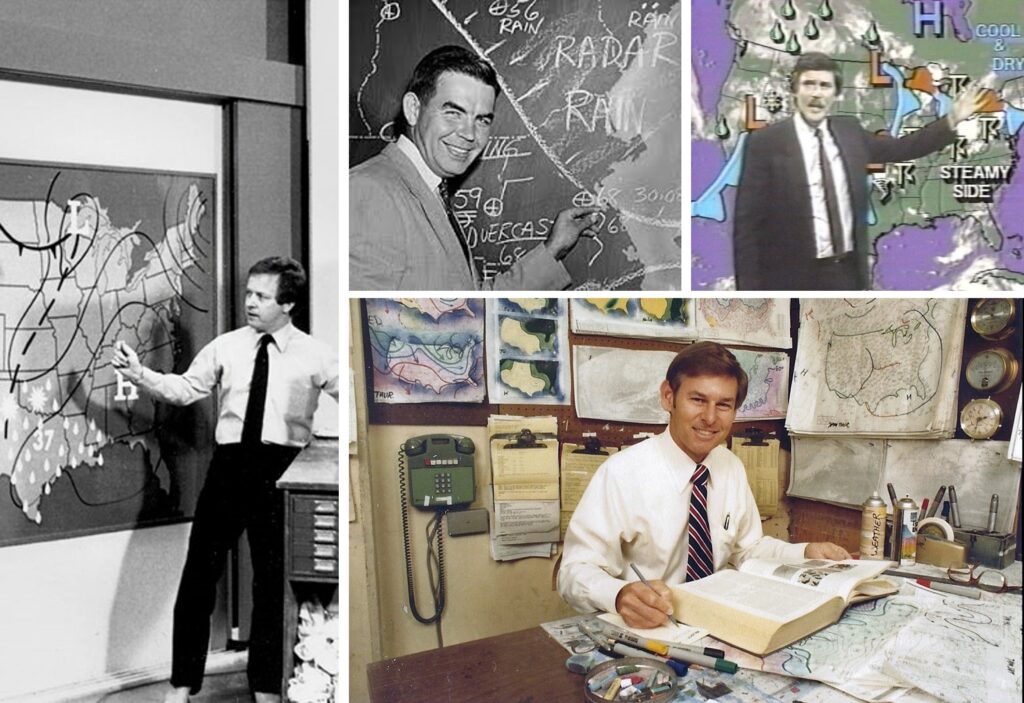

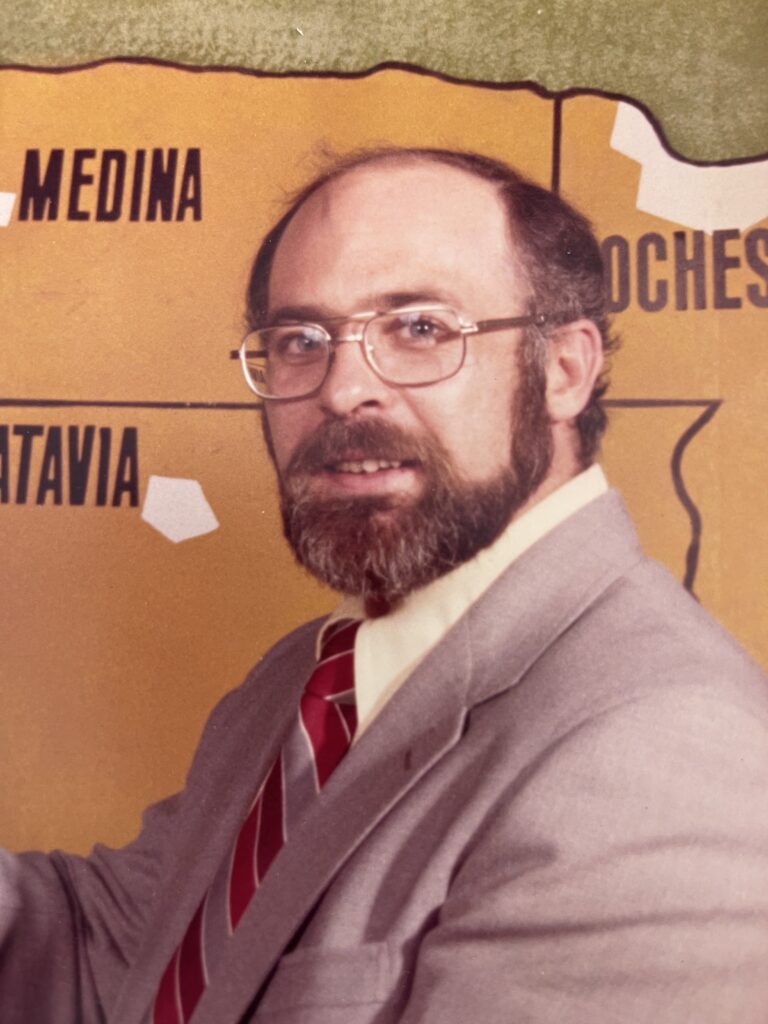

In 1972, she became the first on-air African American female meteorologist, working for WGR-TV in Buffalo, New York (and soon after, became the station’s chief meteorologist). That same year, she was the first woman and first Black American to be given the AMS Seal of Approval for excellence in broadcast meteorology. In 1975, she co-founded the AMS Board on Women and Minorities, now called the Board on Representation, Accessibility, Inclusion, and Diversity (BRAID).

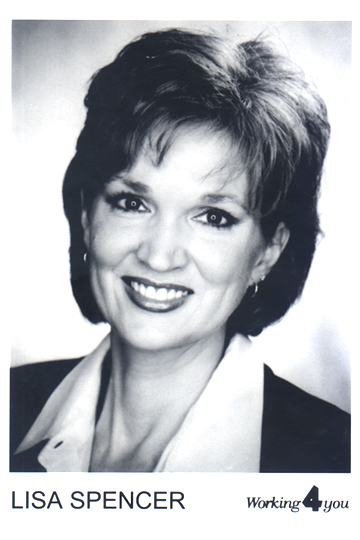

June Bacon-Bercey. Image: AMS.

June Bacon-Bercey was a truly multifaceted scientist: over the course of her life, she was an engineer, a radar meteorologist, and a science reporter. She established a meteorology lab at Jackson State University, created a scholarship with the American Geophysical Union, earned a Master of Public Administration, and even served as a substitute math and science teacher well into her 80s. Not only did she achieve so much personally, but she was instrumental in making atmospheric sciences more accessible to minorities and to women.

I’m grateful to her for leaving all of us at AMS such a rich legacy, and hope you are too! Her determination and foresight benefit us all to this day.

Anna Mani (1918–2001)

Despite growing up in the same city where Anna Mani worked at the India Meteorological Department, I learned of her immense contributions to the field only recently. She followed her passion to study meteorology at a time when it was uncommon for women to pursue science. Although it went unseen by many, Mani’s work was instrumental (literally) in advancing meteorological research in India. Anna Mani once said, “Me being a woman had absolutely no bearing on what I chose to do with my life.”

Thwarted from studying medicine as a young woman, she developed a passion for physics, studied the properties of diamonds, and eventually earned a scholarship to study abroad, learning as much as she could about meteorological instruments. Returning to India just after the country’s independence, Mani played an important role in developing Indian-made weather and climate observing instruments, helping the country become more self-reliant. Her ozonesonde—the first developed in India—was created in 1964 and used by India’s Antarctic expeditions for decades; in the 1980s, these ozonesonde data helped corroborate the presence of the ozone hole in the Antarctic.

She eventually became deputy director-general of the India Meteorological Department. She also held multiple elected positions with the World Meteorological Organization related to instrumentation, radiation climatology, and more.

After (nominally) retiring in 1976, she spent the next few decades—almost till the end of her life—heading up a field research project unit assessing wind and solar energy resources. That work paved the way for many wind and solar farms across the country, advancing India’s leadership in renewable energy. How prescient her thinking was in terms of the need to move away from fossil fuels to renewable energy resources for the health of the environment!

Eunice Newton Foote (1819–1888)

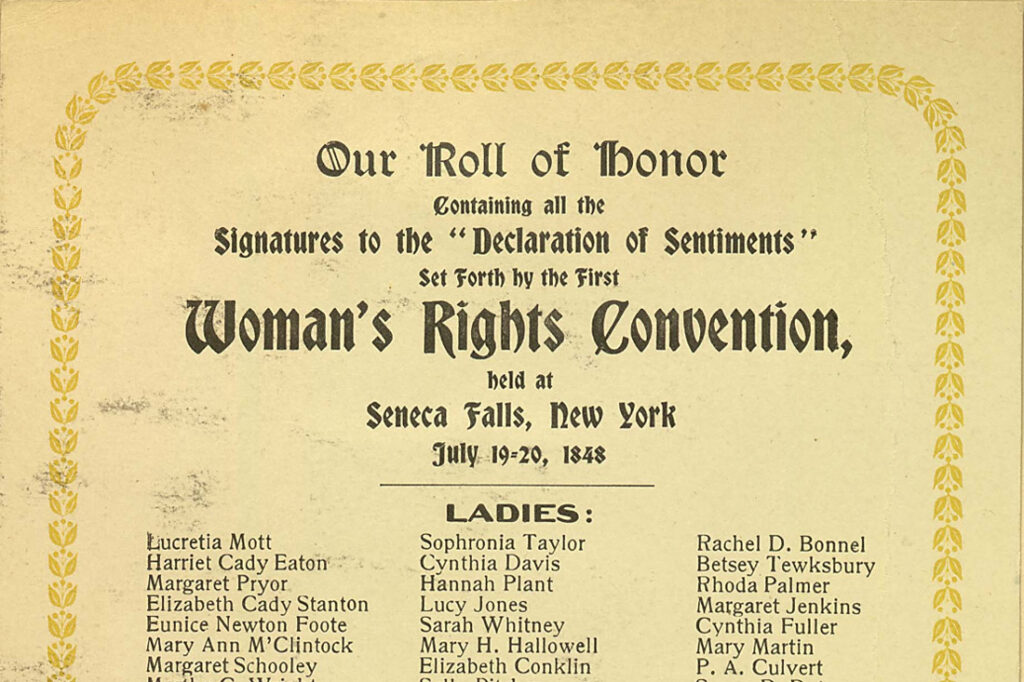

By all counts, Eunice Foote was a remarkable woman. She was a dedicated women’s rights campaigner and suffragist, who attended the historic 1848 Seneca Falls Convention, helped publish its proceedings, and was among the first signatories on its Declaration of Sentiments.

In 1856 she was also the first person to demonstrate heat absorption by atmospheric gases and their potential climate impacts. Using a mercury thermometer inside glass cylinders, Foote found that the heating effect of the sun was greater in moist air than dry air, and highest of all for carbon dioxide. She even suggested that higher proportions of atmospheric CO2 could have caused warmer climates over the course of Earth’s history.

Yet the findings of a female amateur scientist—including the first non-astronomical physics paper published by an American woman—were ignored or dismissed by many at the time. Possibly unaware of Foote’s work, a few years later John Tyndall from Ireland wrote his seminal paper on the topic of atmospheric gases and solar radiation in 1861, and he was credited with the discovery of the greenhouse effect.

That didn’t stop Foote, who would publish another physics paper and produce several patented inventions including a temperature-controlled stove. Though she spoke out about women being forced to file her patents under their husbands’ names for legal reasons, she still filed three under her own name, including rubber shoe-inserts and a paper-making machine. As a scientist, inventor, and women’s right campaigner, Eunice Foote was a trailblazer in the true sense of the word.

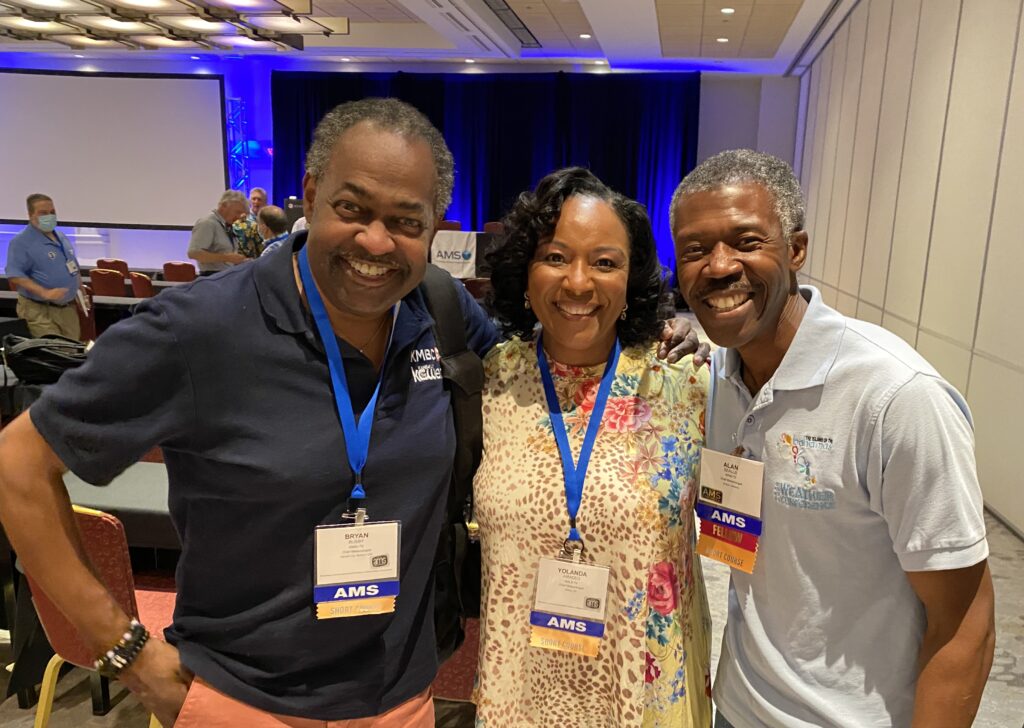

Women continue to break barriers!

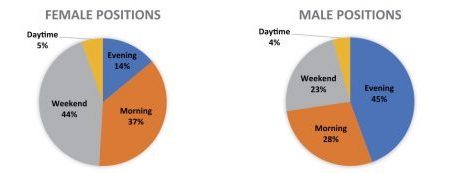

Women, and especially women of color, still face barriers to equal participation and recognition within our fields. There are women whose names we *should* all recognize, but whose work has been buried, others whose ambitions may have been thwarted, or who are still struggling to be taken seriously. Whoever and wherever you may be, you can do your bit to help change that. By giving credit where it is due, we do right by each other and help make the meteorological ecosystem an attractive place to join, work, and collaborate in.

I would invite all of us to make a special effort to recognize the women we know who are making important contributions in Earth systems sciences—not just the ones who’ve already made a name for themselves, beating the odds. Mentor the early career scientists you know. Appreciate their talents and potential. Champion their careers. Consider nominating those you consider meritorious for AMS awards (including the Joanne Simpson Award and the June Bacon-Bercey Award!). If you’re part of the AMS community, consider following in the footsteps of June Bacon-Bercey by getting involved with BRAID’s efforts to make our field more welcoming for all who have a passion to be part it—including women, people of color, LGBTQ+ people, and those with disabilities. Or you might simply view and share this month’s AMS social media posts, celebrating women in our community. Happy Women’s History Month!

Anjuli is grateful to Katherine ‘Katie’ Pflaumer for providing useful edits as well as contributing material.

Listen from the

Listen from the