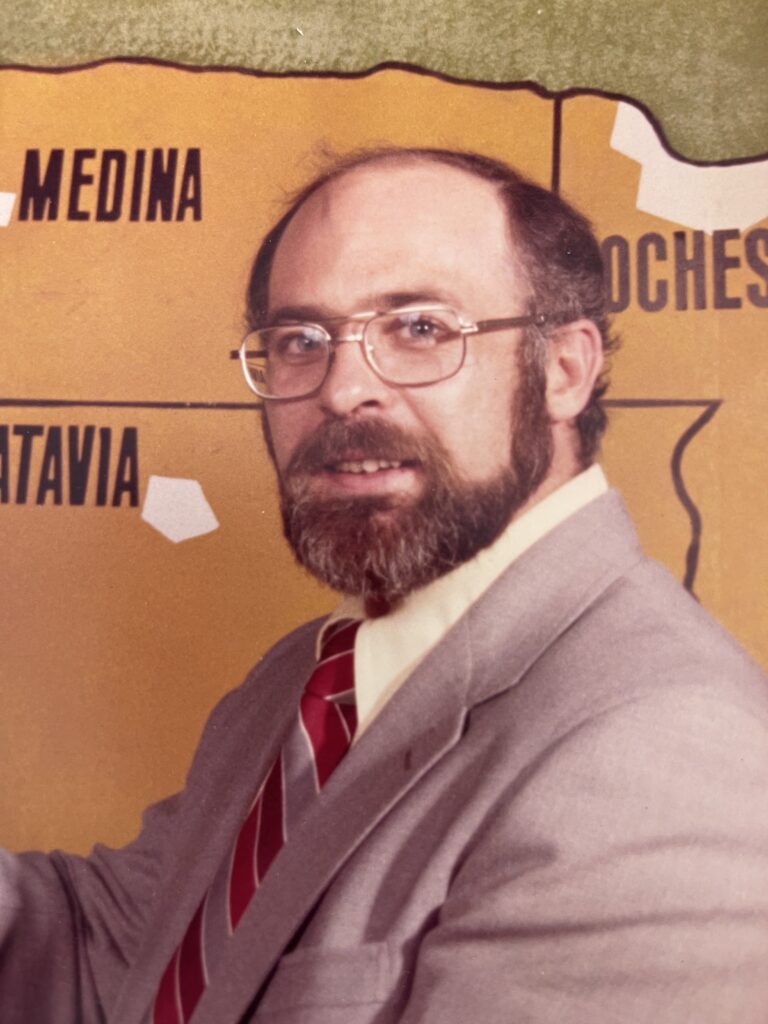

Lessons from Longtime Broadcast Meteorologists

In the third of three posts celebrating the 50th Conference on Broadcast Meteorology, we asked longtime broadcast meteorologists about what it means to do what they do, and their advice for others in the field.

What are some historic weather events you’ve covered, and what did you learn?

“It’s easy to joke with the news anchors and talk about a beautiful 75-degree day. But when severe or extreme weather approaches, the true essence of a broadcast meteorologist’s role is public safety. The first two weeks of 1999 was one of the harshest stretches of winter weather the Detroit area has ever seen, and I was out reporting live [when] people were struggling to get to work… [It was so cold] that roads salted the previous afternoon had an overnight refreeze … I cautioned people [that] if they were the first car at a stop light and it turned green, to pause a moment to make sure that nobody was skidding through the intersection before proceeding through. Later in the day, a viewer e-mailed to tell me that I had directly saved her life … that she was stopped at a light and, when it turned green, was about to hit the accelerator like normal, then remembered what I had said. She put her foot back on the brake. At that moment, a panel truck came barreling across the intersection from the left. Had she proceeded without pausing, she likely would have been broadsided and killed.

Paul Gross, AMS Fellow, CCM and CBM

No matter if it’s a severe winter storm, thunderstorm, tornado, hurricane, flash flood, or any other significant natural hazard, our job as broadcast meteorologists is to take the viewers by the hand and help them make informed decisions that could save their lives. Nobody [else] in broadcast media has this responsibility on a daily basis. And there is no greater compliment than when somebody says ‘you saved my life.’”

“There have been many historic weather events from Hurricanes Andrew, Fran, and Floyd to numerous tornado outbreaks in Middle Tennessee. The one event that stands out the most is the Great Flood of 2010 that impacted Tennessee with record rainfall totals and historic flooding. Interstates became raging rivers; neighborhoods were submerged in water and even downtown Nashville was flooded with several feet of water coving streets. Over 30 people lost their lives.

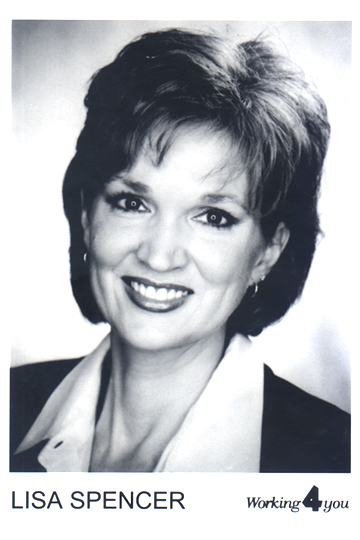

Lisa Spencer, Chief Meteorologist, News4, Nashville, Tennessee

From all these events I have learned how much people in my community rely on me for critical information to help them prepare, survive and recover. It’s so important for me to deliver that information in a calm but urgent tone.”

“The Barneveld F-5 Tornado in June 1984 was an early event that I covered. Nine people lost their lives in that terrible storm and it hit at 1 a.m. It had a major impact on me in terms of staying late into the night if necessary to issue warnings. In my St. Louis years, there were often times that I would stay after the late news to cover thunderstorm complexes and not get home until 5 a.m. In Denver, our thunderstorms tend to be in the afternoon and evening – but I have spent many nights here covering blizzards!

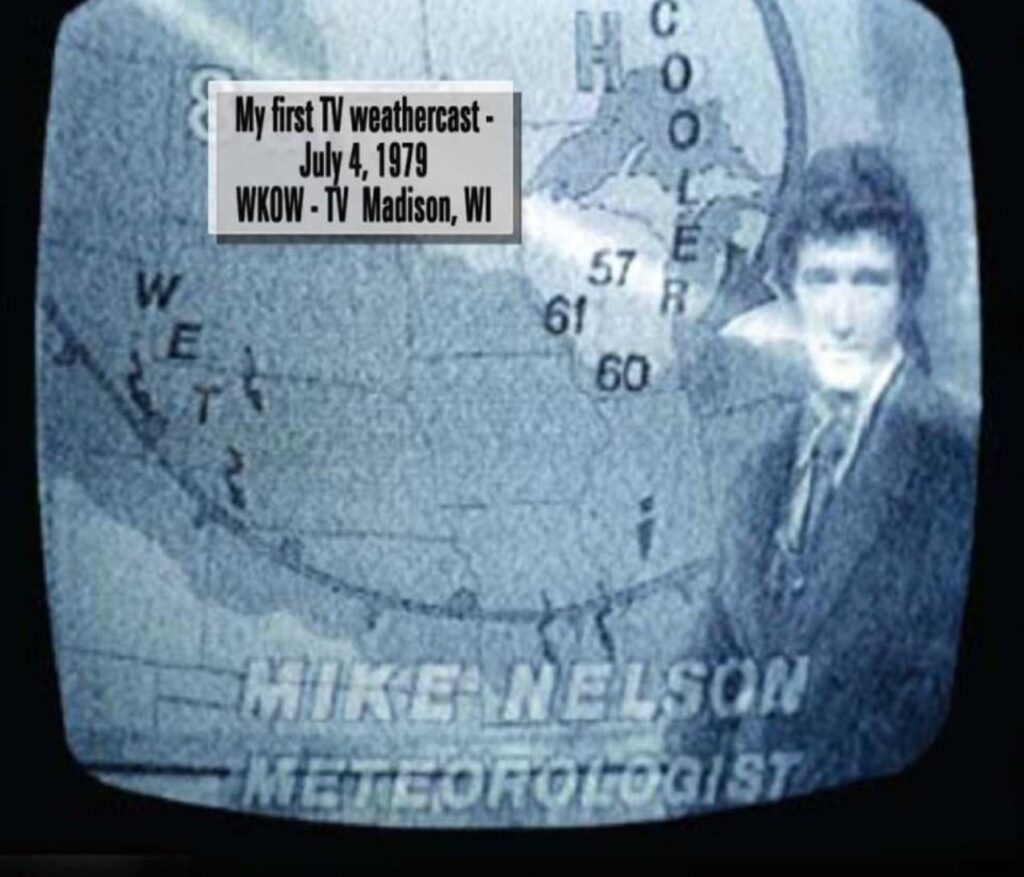

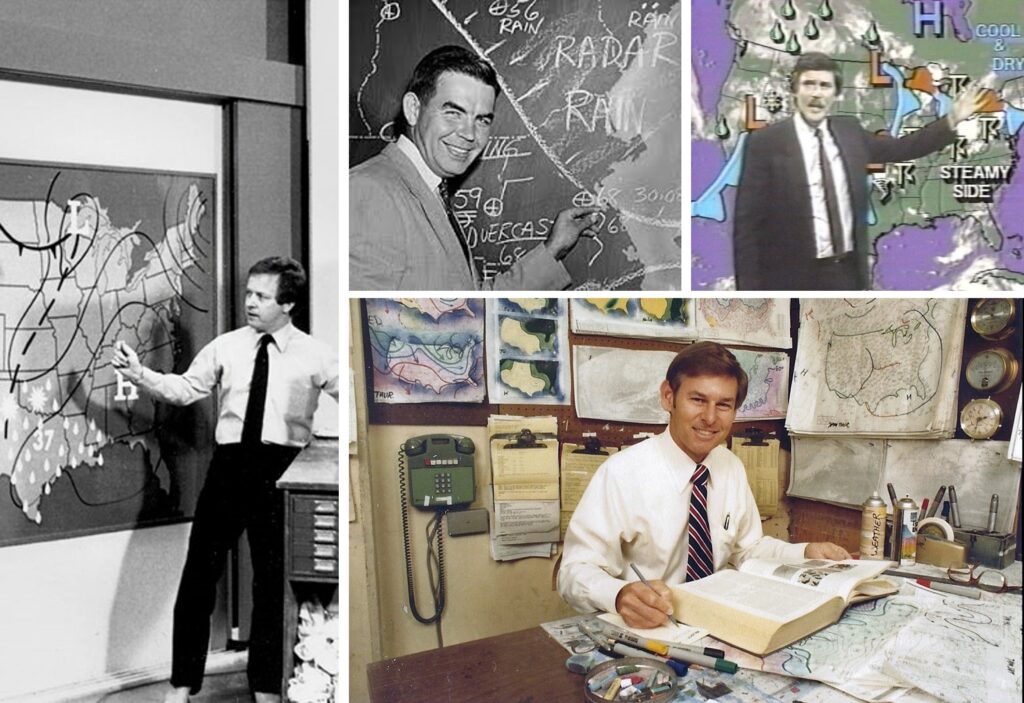

Mike Nelson, Denver7 Chief Meteorologist, KMGH, Denver, Colorado

Most recently, we had a massive wildfire in December 2021 that destroyed nearly 6,000 buildings just south of Boulder, Colorado. The Marshall Fire was a huge firestorm caused in part by very warm and dry weather – related to climate change. I try to incorporate the climate change connection into my weather reports as often as possible.”

What does being a Certified Broadcast Meteorologist mean to you?

“I find great value in the CBM program. I served on the committee to develop the seal program. In addition, I also helped develop the first test and testing guide.

Lisa Spencer, Chief Meteorologist, News4, Nashville, Tennessee

When I see that someone has earned the CBM seal, I know that they have gone through a rigorous test to demonstrate their expertise in the field. Additionally, I am confident in their communication skills knowing their work has been reviewed by a group of experienced peers. CBM seal holders have gone the extra mile to make sure they are equipped to deliver critical weather and science information to their communities.”

“I am CBM number 50, so I have had the designation for a while. The CBM represents the highest level of certification that the AMS can provide to a broadcast meteorologist and it should be held with high esteem. It takes a lot of work to achieve and should merit respect from the TV stations, networks and – most important – the viewer. As CBMs, we have a unique opportunity and responsibility to educate our viewers about weather, science and climate change.”

Mike Nelson, Denver7 Chief Meteorologist, KMGH, Denver, Colorado

What are some lessons you’d like to share with other broadcasters?

“Be active in the community, visit schools, answer all your email, educate the public about climate change. Also, the years go by faster than you will imagine – be sure to plan for your financial future as this business is not getting easier and will never pay as well as it did during my career (sorry)!”

Mike Nelson, Denver7 Chief Meteorologist, KMGH, Denver, Colorado

“Be yourself, be humble, stay focused, set goals and have fun!”

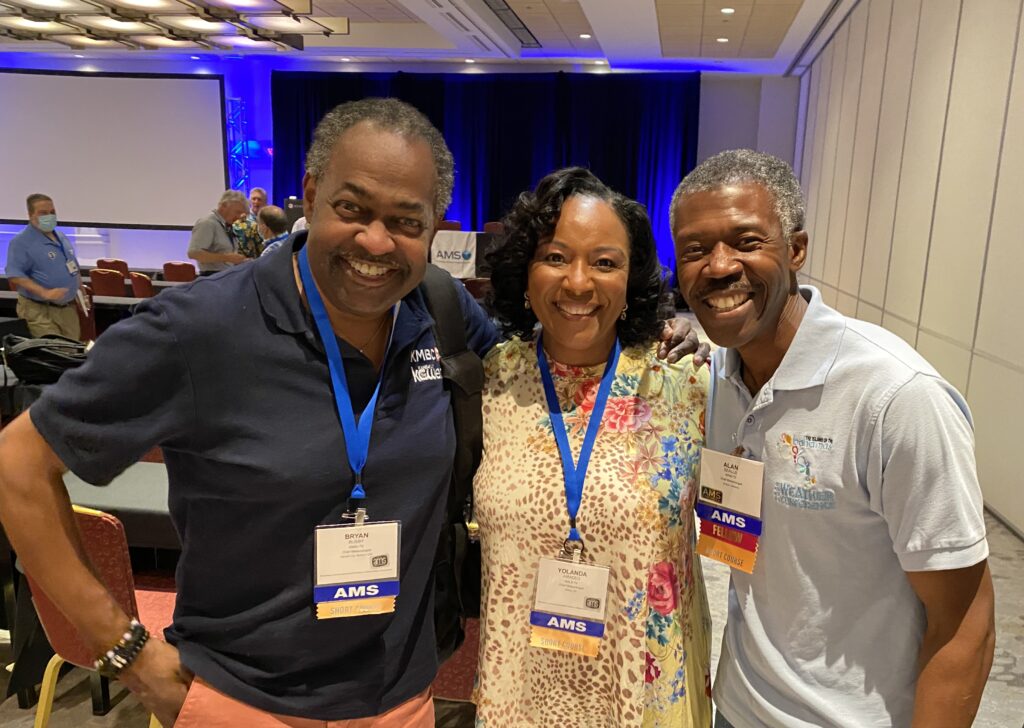

Yolanda Amadeo, Chief Meteorologist, WALB News, Albany, Georgia

“From my over-35-year career as a broadcast meteorologist, I have learned the one thing you can count on is change… change in management at all levels, change in responsibilities, and change in the technology and the way we present the weather. But with all those changes we have to remember what we are there for… to serve our communities with the most accurate, informative weather information especially in critical times. When someone recognizes you in public and acts like they know you personally… that’s a good thing. You have made a connection and are welcomed in their home, on the TV or whatever device they are using to watch you. I try to always be gracious.”

Lisa Spencer, Chief Meteorologist, News4, Nashville, Tennessee

About 50Broadcast

The 50th Conference on Broadcast Meteorology took place in Phoenix, Arizona, June 21-23, 2023. It was organized by the American Meteorological Society Board on Broadcast Meteorology and chaired by Danielle Breezy and Vanessa Alonso.

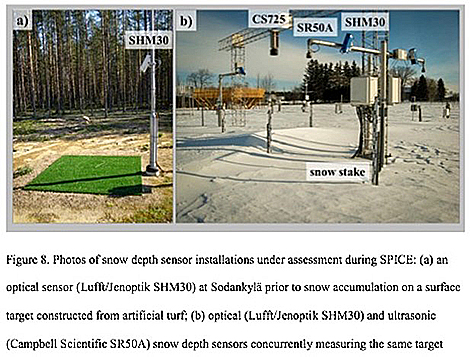

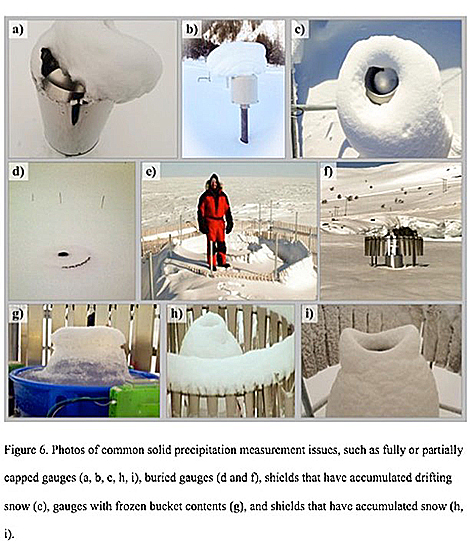

Meanwhile, Kochenderfer et al. note a proliferation of automated gauges and new non-catchment methods that involve using laser disdrometers and “present-weather” detectors to remotely determine what type of precipitation is falling.

Meanwhile, Kochenderfer et al. note a proliferation of automated gauges and new non-catchment methods that involve using laser disdrometers and “present-weather” detectors to remotely determine what type of precipitation is falling.