Uncontrollable sources of ozone from stratospheric intrusions, wildfires, and intercontinental transport are complicating efforts in California to further reduce this pollutant, which is particularly harmful to our health.

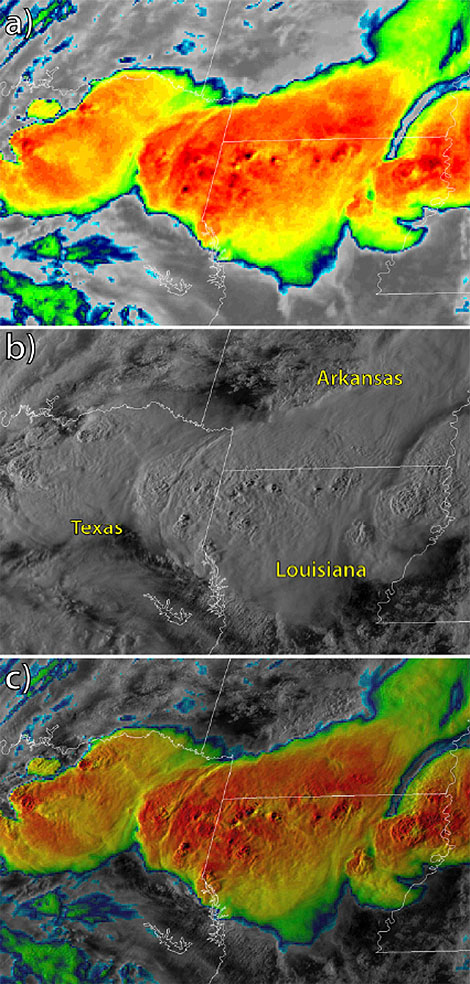

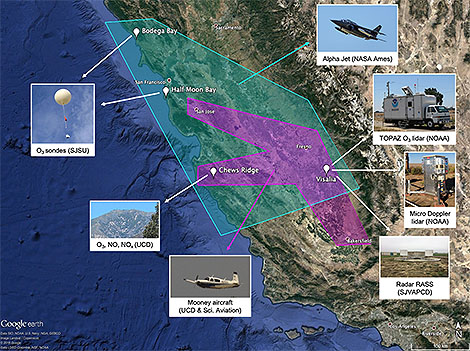

Scientists measured daily fluctuations in ozone in the air across Northern and Central California in 2016 during a coordinated field campaign known as the California Baseline Ozone Transport Study. They particularly focused on ozone crossing the shoreline and accumulating in low level air over the San Joaquin Valley.

Ian Faloona (University of California, Davis) and colleagues summarize the measurements and unique meteorological context for this novel dataset in a recent article published in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Faloona et al. draw attention to the dataset’s potential for future modeling studies of the impacts of long-range transport on regional air quality.

Falloona, in his cockpit perch during aerial measurements for CABOTS.

We asked lead author Faloona to help us understand CABOTS and his motivations for this work.

BAMS: What would you like readers to learn from this article?

Faloona: I think this article presents a nice overview of the mesoscale flow over the complex terrain of Central and Northern California, and I would like readers to become more appreciative of the global nature of air pollution. The field of air quality was once considered in terms of emissions and receptors within “air basins” but as our knowledge of the global nature of greenhouse gases in terms of climate change has developed, I believe that we have similarly become more and more aware of the global aspects of many air pollutants in general.

How did you become interested in the topic of this article?

Some colleagues from the UC Davis Air Quality Research Center and I became interested in long-range transport of air pollution to California and how it might be best sampled along the coastal mountains where local emissions might be minimal and the surface was well above the strong temperature inversion of the marine boundary layer. We eventually found the site on Chews Ridge where a group of renegade astronomers had been operating an off-the-grid observatory with the Monterey Institute for Research in Astronomy. They allowed us to build a climate monitoring site collocated with their observatory (the Oliver Observing Station) and then some airborne work for the San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District allowed us to link the inflow at the coast to air quality issues within the leeward valley.

What got you initially interested in meteorology or in the related field you are in?

While an undergraduate studying physical chemistry I wrote a term paper on acid rain for a chemical oceanography class. I was floored by how few details were thoroughly understood about the chemical mechanisms of an environmental problem that at the time was considered quite serious. I figured I should throw whatever brainpower heft I could into this type of atmospheric oxidation chemistry. But then, while working for a private consulting company in Colorado after college, many of my colleagues there were trained in meteorology and I knew there would be little progress without a fundamental understanding that field. So I went to Penn State to do chemistry research but get trained in all aspects of meteorology.

What surprises/surprised you the most about the work you document in this article?

The first thing that surprised me about the data we collected for CABOTS was how deep the daytime up-valley flow was (~1.5 km), but how shallow the convective boundary layers tended to be (~0.5 km). The scale interactions that need to be taken into account when analyzing boundary layers among the complex terrain of California make it a great place to study in meteorology. But the other major discovery that came out of this work was the evidence we found of significant NOx emissions from certain agricultural regions in the San Joaquin Valley. For instance, we found that the agricultural region between Fresno and Visalia was responsible for as much NOx emitted to the valley atmosphere as from all the mobile sources in the CARB inventory across the three county region.

What was the biggest challenge you encountered while doing this work?

The sensible heat at the Fresno airport. Our airborne deployments attempted to target high ozone episodes, which are best forecast by their correlation with ambient temperatures. I like to tell my students that I am a chaser of extreme weather. It just so happens that the weather features most important to air quality are heat waves. Heat waves are extremely easy to catch, and can be brutal in their persistence. Some days we observed temperatures in the plane on the tarmac of >115 ºF, which made it challenging to keep the equipment up and running. I remember dragging bags of ice in and out of the plane covered in sweat, and still having the instruments give up in heat exhaustion before one of our midday flights.

What’s next? How will you follow up?

I would like to continue studying the various scales at play in the transport of intercontinental pollution to North America, and my preferred tools are aircraft laboratories. I would like to follow up with a study of wintertime stagnation events that lead to particulate matter air quality problems – an entirely different meteorological beast. But I would also like to follow up with a study of agricultural NOx emissions in the Imperial Valley of Southern California. This region is expected to have the largest soil emissions and the lowest urban sources to confound the measurements. It is also a region of important environmental justice issues being made up largely of migrant agricultural workers who have to bear the burden of the air quality problems engendered by agriculture.

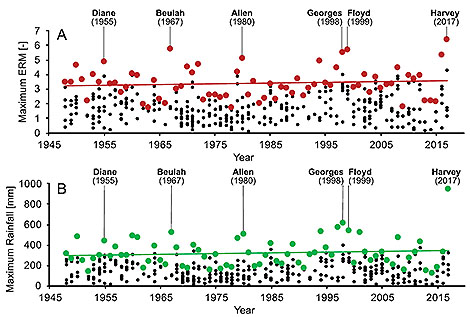

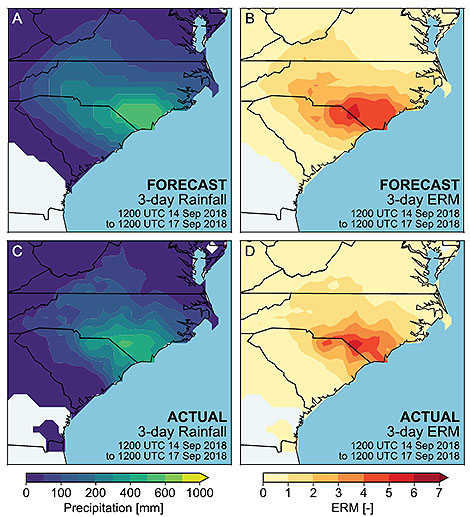

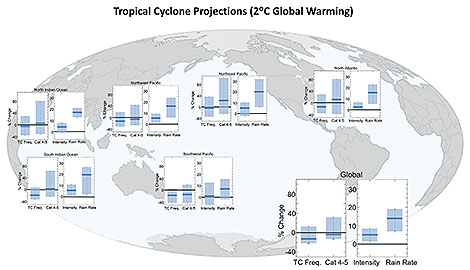

Flooding rainfall already is the most deadly hazard from tropical cyclones (TCs), which include hurricanes and tropical storms. Yet the widely recognized tool for conveying potential tropical cyclone destruction is the

Flooding rainfall already is the most deadly hazard from tropical cyclones (TCs), which include hurricanes and tropical storms. Yet the widely recognized tool for conveying potential tropical cyclone destruction is the

North American meteorologists, welcome to the snow climate of western Japan. Every year in winter lake effect-like snow events bury coastal cities in northern and central Japan under 20-30 feet of snow. Above is the “snow corridor” experienced each spring when the Tateyama Kurobe Alpine Route through the Hida Mountains reopens, revealing the season’s snows in its towering walls. The Hida Mountains, where upwards of 512 inches of snow on average accumulates each winter, are known as the northern Japanese Alps.

North American meteorologists, welcome to the snow climate of western Japan. Every year in winter lake effect-like snow events bury coastal cities in northern and central Japan under 20-30 feet of snow. Above is the “snow corridor” experienced each spring when the Tateyama Kurobe Alpine Route through the Hida Mountains reopens, revealing the season’s snows in its towering walls. The Hida Mountains, where upwards of 512 inches of snow on average accumulates each winter, are known as the northern Japanese Alps.