Every journey begins somewhere—sometimes all you need to do is start heading down a path.

This year AMS Past-President Fed Carr has given our Annual Meeting a destination: a comprehensive consideration of our observing needs. He’s also given us a place to embark on our journey: the Presidential Forum this morning (9 AM, Ballroom 6ABC) in which moderator Vanda Grubišić and her distinguished panel take us on a guided tour of our community’s capabilities and a glimpse of the multidisciplinary realms just beyond our reach.

This year AMS Past-President Fed Carr has given our Annual Meeting a destination: a comprehensive consideration of our observing needs. He’s also given us a place to embark on our journey: the Presidential Forum this morning (9 AM, Ballroom 6ABC) in which moderator Vanda Grubišić and her distinguished panel take us on a guided tour of our community’s capabilities and a glimpse of the multidisciplinary realms just beyond our reach.

He’s given us everything but the actual path. That choice is yours.

One option that beckons right from the Forum is the path of innovative platforms and systems that continually expand the ways we observe. It’s a path that travels across land, through air and water. It requires vehicles of all kinds and sizes, and takes your quest through every byway of modeling, theory, services, products, and yes, even observations, in search of our observational needs for the future .

Let’s look at a few of the milestones along the path of alternative observing, if you choose to take it.

Roadways themselves are paths, of course, and the Annual Meeting will showcase the new ways roads are a vital part of observing. On Tuesday (9:15 AM), Jeremy Paul Duensing of Schneider Electric will examine the success of Alberta Transportation’s road weather sensor network. One of the largest intelligent road observing systems in North America, this network features sensors taking 100 readings per second directly on vehicles.

Also on Tuesday, at 9:30 AM, Amanda Anderson of NCAR will review the Wyoming Department of Transportation’s project to collect weather (and other) data from internet-connected vehicles traveling on the state’s portion of I-80, which is prone to all sorts of hazardous conditions from blizzards to wildfires.

Meanwhile, the Oklahoma DOT combines a roadside weather information system with modeling and GIS visualization software to monitor road icing hazards. Benjamin Toms of the University of Oklahoma will discuss this system on Tuesday at 11:15 AM.

Our emerging technologies pathway extends skyward, too. On Wednesday at 9:45 AM, learn more from Djamal Khelif of the University of California, Irvine, about the Controlled Towed Vehicle (CTV), which utilizes improved towed-drone technology to measure spatial and temporal variability of sea surface temperatures, wind, temperature, and humidity, as well as turbulent air-sea fluxes from observations made as low as eight meters.

Range into space as well—you no longer need big, complicated satellites to get there. On Wednesday at 8:45 AM, as William Blackwell of MIT Lincoln Laboratory explores the capabilities of CubeSats in microwave high-resolution atmospheric remote sensing. James Clemmons of The Aerospace Corporation will investigate the potential uses of CubeSats in space weather research on Monday at 4:30 PM .

The path even extends onto and into the water. On Monday at 4 PM, Maricarmen Guerra Paris of the University of Washington will review a project that utilizes ferries equipped with Acoustic Doppler Current Profilers to provide full-depth profiles of currents and distinguish tidal currents adjacent to Puget Sound.

The Annual Meeting is full of such unconventional paths—paths of invention paving the way to observation. It’s time to make the choice and your journey.

News

Good Enough for Ethics

At his blog, Living on the Real World, AMS Associate Executive Director William Hooke makes a compelling prediction for the next four years: Ethics will matter more than ever.

He’s not talking about politicians, necessarily. He’s talking about our ethics, as members of the atmospheric sciences community. His reasoning? Our capabilities in making predictions are getting that good:

In this high-stakes environment where the products and services we provide are the basis for action, ethics matter. When can and should a NWS field forecaster begin to act when numerical guidance appears to diverge from on-the-ground reality? What observations, products and services should be considered public goods? What can and should be privatized? What’s at stake with warn-on-forecast? To list these few examples doesn’t do justice to the dozens of ethical dimensions to the daily work of everyone in every corner of today’s Earth observations, science, and services community.

At the AMS Annual Meeting on Sunday, Tom Ackerman (meteorologist/climatologist) and Steve Gardiner (philosopher/ethicist) of the University of Washington will moderate a panel session on ethics (1:30 to 3:30 p.m.; Room 613).

Gardiner is the author of the book, A Perfect Moral Storm: The Ethical Tragedy of Climate Change, in which he describes the way this environmental hazard combines many of the classic types of ethical dilemmas found separately in other threats to civil society. The challenges include incomplete knowledge and the uneven distribution of exposures to risk, incentives for action, and burdens of cost—across geography as well as economic classes and generations.

To get a taste of the discussions this week, try this lecture in which Gardiner shows how 200 years ago Jane Austen anticipated the perfect storm of ethical challenges of climate change.

Then follow up Sunday’s sessions by attending “Shades of Gray: Panel Discussion on Ethics, Law, and Uncertainty in the Weather, Water, and Climate Community,” on Wednesday (8:30 a.m., Room 613):

Though our Enterprise is indeed motivated by altruistic interests, ethical gray zones emerge. How confident are we in that climate model, and what should we disclose? Should we attempt to create a forecast beyond 7-14 days? What is the proper balance between providing information and urging action? The presentation of scientific uncertainty can be fraught with misinterpretation and resistance, particularly from non-scientists.

For Climate Science, Transitions Continue

The Inauguration of Donald Trump yesterday marked the end of the Transition. Yet, the end of the Transition with a big “T” marks the beginning of small “t” transitions for everyone else—political winners and losers alike.

According to Reed College historian Joshua Howe, climate science is particularly affected by such changes, absorbing and adapting to shifts in political winds for many decades. The continually transitioning relationship climate science has forged with politics—especially environmental politics—is chronicled in Howe’s book, Behind the Curve: Science and the Politics of Global Warming (Univ. of Washington Press, 2014).

As a past recipient of the AMS Graduate Fellowship in the History of Science, Howe presented the basics of his book at the 2009 AMS Annual Meeting. His dissertation was expanded into the book. In a recent interview at New Books Network (listen here), Howe explains how climate scientists have had to reinvent their approach to environmental advocacy. In Howe’s view, the approach politically active scientists took to triggering action on climate change simply didn’t work well, making the field ripe for further transition.

It was clear early on that climate change, as an environmental concern, was unprecedented in scale and complexity. Following on the debate in the 1970s over the nation’s Supersonic Transport program, atmospheric science had won a place at the environmental table. But environmentalists were used to dealing with local pollution and wilderness access—clear quality of life issues that resonated with their middle class constituency, Howe says. They were interested in concrete, simple, nontechnical issues they could rally around—and climate change was too complex to fit those parameters. Climate change wasn’t a low-hanging fruit ripe for political victories.

Meanwhile, the issue of nuclear winter provided a further, politically loaded impetus to the climate community, Howe said. But the result was a split, with some scientists becoming more politically outspoken within the environmental movement, while others became more entrenched within a conservative physical science community. As a result, the relationship of government funding to climate science became politically fraught.

Scientists initially reached out on climate change through the government agencies in the 1970s. Howe points out that “working within government bureaucracies left scientists vulnerable to political change.” The Carter administration shifted directions; Reagan then arrived with budget cuts and curtailed access to bureaucracy.

In response, many climate scientists sought a technical consensus that might force political action by the shear power of knowledge. The scientists attacking the problem in the 1970s onward had, as Howe puts it, a “naïve” attitude.

“Better knowledge, climate scientists believed, would lead to better policy,” Howe said in his 2009 AMS presentation. “Perhaps it is time for scientists to drop the false veil of political neutrality and begin discussing science and politics as two sides of the same coin.”

The AMS Annual Meeting in Seattle is an ideal opportunity to ponder the future of the atmospheric sciences during the next four years. Check out the Monday Town Hall on “Climate Change – How can we make this a national priority?” (12:15 p.m., Room 613). Then attend the panel session on priorities of the Trump Administration and Congress later that day (4 p.m., same room). The panelists include Ray Ban, Fern Gibbons, and Barry Lee Myers.

The Network of Mutuality at the AMS Annual Meeting

“We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny” wrote Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., from a jail cell in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963. “Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly….Anyone who lives inside the United States can never be considered an outsider anywhere within its borders.”

On this day, each year, Americans honor Dr. King’s achievements. Yet realizing his goal of peace, justice, and empathy remains a challenge in a diverse society that continues to sort itself racially, ethnically, economically, and geographically. It takes action year-round to advance Dr. King’s social justice vision.

There are many members of our AMS community who, in their own ways, are answering that call to action. The themes of Martin Luther King Day will be fresh on our minds next week at our 97th AMS Annual Meeting in Seattle–consider taking time to weave your way into that “network of mutuality” by attending some of the many presentations on diversity in the sciences. For example:

- PROGRESS: PROmoting Geoscience Research Education and SuccesS Through Deliberate Mentoring will present preliminary analyses of online surveys and interviews with female undergraduate student participants of a mentoring program aimed at increasing the interest, persistence, and achievement of undergraduate women in geoscience fields, including atmospheric science.

- Achieving Greater Diversity in Atmospheric Science: Translating Best Practices into Success will highlight the methods the CSU Department of Atmospheric Science used to increase diversity in atmospheric science, in hopes that they can be replicated in other geoscience departments across the nation.

- UCAR/NCAR Equity and Inclusion (UNEION): Addressing Diversity, Equity and Inclusion at a Major National Laboratory addressed workplace climate through a 4-part intensive training series for employees, covering privilege, gender, race, and bystander intervention techniques to change attitudes towards diversity and inclusion in the workplace.

- Exposing Underrepresented Groups to Climate Change and Atmospheric Science Through Service Learning and Community-Based Participatory Research explains how Tennessee State University is participating with six other institutions in this NASA-funded project to expose high school students from racial and ethnic groups traditionally underrepresented in STEM to atmospheric science and physical systems associated with climate change.

- The New York City College of Technology has forged Federal, Local, Private, and Institutional Partnerships for Promoting and Enhancing Diversity in the Geosciences as a way to train, equip, and retain students in the geosciences to successfully enter the geoscience workforce.

- Citrus College, a Hispanic-serving two-year public community college in northeast Los Angeles county, is Partnering for Diversity: A Year-Round Experiential Learning Project to Engage Community College Students in the Geosciences, working with the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) and UCAR to do the same thing as the New York City College of Technology but at the community college level. “A peak experience of the program is a ten-day mini-internship in Colorado where students are immersed in atmospheric research, training, and fieldwork,” the abstract of this presentation states.

There are posters, too, that look at diversity and programs that assist minority students and faculty teaching at minority-serving institutions:

- A Three-Year Success Story: AMS Climate Studies for the Diverse Student Population at the University of Hawaii West Oahu discusses the findings from three years of surveys of students enrolled in a meteorology course as a viable approach to STEM and Climate Literacy for a very diverse population of students.

- Improving Academic Performance and Retention for Environmental Sciences and Engineering Urban Students are the main goals of a partnership among minority and Hispanic-serving institutions in New York City, and results of the five-year program exemplify the successful coordination and integration of modular programs and intervention strategies.

- Latin American Network of students in Atmospheric Sciences and Meteorology (RedLAtM) promotes the integration of young people towards a common and imminent future: Facing the still unstudied various weather and climate events occurring in Latin America and Mexico.

- The AMS Education Program highlights several initiatives Using Real-World Data to Train Faculty at Minority-Serving Institutions that promote the use of real-world data while increasing diversity in the AMS-related fields.

GOES-R: Are You Ready for Something Awesome?

By Jonathan Malay, AMS Past-president and retired Lockheed Martin Washington Operations

I’m sorry to say, the word “awesome” seems way overused these days. OK, it’s pretty funny when Cecily Strong’s character on Saturday Night Live’s “Girl Talk” sketch keeps saying “Awesome!” That’s amusing, but it’s not awesome. Awesome is a word we simply can’t help ourselves from using when we’re really blown away by something, like when we gaze at the natural miracle of the Grand Canyon below us, or when we behold the immensity, both in size and raw emotional impact, of the new One Trade Center in southern Manhattan, or when we see an Olympic record being broken.

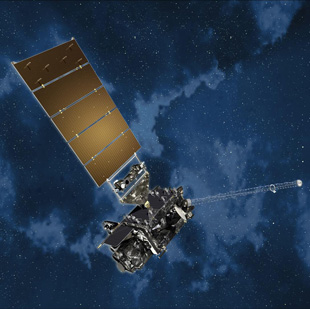

As a meteorologist and a space guy, I’ve been fortunate enough to look up at the Space Shuttle from the foot of its launch pad at Cape Canaveral. I’ve seen the brilliant flames when the mission lifted off, and, a few seconds later, felt the vibrations of sound waves penetrate all the way to my bones. I stood in a clean room at the Stennis Space Center a few years ago where I saw, and actually touched, the initial structure and propulsion module of GOES-R, a spacecraft destined to become the first of a new and revolutionary generation of geostationary meteorological satellites. I can honestly say these things I saw and felt were really and truly awesome.

If the schedule holds, at 5:42 p.m. this Saturday, November 19, that satellite will be launched. Thousands of eyes, either in spectator locations, or in mission control rooms, at National Weather Service centers, on big-screen TVs, on computer monitors, or even on handheld devices, will watch the magnificent white- and copper-colored Atlas V as its powerful RD-180 engines ignite and send the GOES-R spacecraft toward its assigned orbit in space. It will be awesome. Really and truly.

GOES-R, which has been some 15 years in the making, is going to deliver to meteorologists, oceanographers, and space weather forecasters at NOAA and everywhere—and to the people of the United States and all the Americas—a truly awesome set of capabilities, such as:

- Three times more spectral information

- Four times greater spatial resolution

- Five times faster coverage

- Real-time mapping of total lightning activity

- Increased thunderstorm and tornado-warning lead time

- Improved hurricane track and intensity forecasts

- Improved monitoring of solar x-ray flux

- Improved monitoring of solar flares and coronal mass ejections

- Improved geomagnetic storm forecasting

By now, AMS members and the meteorological community are probably aware of the improvements GOES-R and the other birds in the series—S, T, and U—will provide over the current GOES-N/O/P-series satellites, which have been in orbit since 2006. This new generation of GOES satellites will far exceed anything we’ve seen before. As someone who lived the GOES-R experience while working at Lockheed Martin in Washington, D.C., I’ve had the privilege of knowing and working with many of the fantastic people who have made it a reality. These folks at NOAA and NASA, on the White House staff, on Capitol Hill, at my great company, at our industry partners, and across the meteorological, oceanographic, and space weather communities . . . there are too many of you to acknowledge individually (except program director Greg Mandt, my good friend and colleague, who truly deserves a special shout-out)—you have all been awesome!

So, along with all my friends in government and at Lockheed Martin Space Systems and the Advanced Technology Center, United Launch Alliance, Harris, Exelis, ATC, LASP, and all the great contractors on the team, we’ll all be watching Saturday’s rocket launch, saying with all our hearts: “GO GOES-R! GO ATLAS!” And then, as the mission disappears in the sky, we’ll all involuntarily say, “Awesome!”

Weathering the North Atlantic in a Rowboat

If you’re planning on rowing 3,300 miles across the North Atlantic Ocean in a 24-foot boat during hurricane season, you can imagine how important a reliable weather forecast would be. Cynthia Way, a chief learning officer at NOAA, is not just going to imagine making this journey; she’s going to do it. This week, she’ll set out from Cape Cod, Massachusetts, to Ireland with her boyfriend, James Caple, a software engineer. The journey will take three to four months, depending on weather and other obstacles they may encounter. If they make it across, they’ll be the first American pair to succeed in the endeavor.

“We want to challenge ourselves to do something amazing, something that is also scary and way out of our comfort zones and will stretch our capabilities,” Way says. And stretch their capabilities is certainly what they’ll be doing. The two will face the grueling physical challenge of constant rowing, sleep deprivation, and mental exhaustion. Way is pursuing a Ph.D., researching how immersion outdoor experiences help people reconnect with nature and is hoping this journey will give her an up-close perspective she’ll be able to utilize in her doctoral research.

For his part, Caple has been planning and preparing for this trip since he read a news article about Roz Savage, a solo ocean rower, who in 2007 rowed across the Indian Ocean. Last year, the couple got in touch with Savage, who has been advising them on safety. “It is a dream come true to have Roz as our expedition mentor after stalking her all these years,” says Caple.

While the challenges will be numerous, what Way fears most is the possibility of encountering bad weather. They’ll be provided with forecasts from a private weather service through satellite phones every three days. Weather reports are crucial to planning. Rowing shifts may need to be altered based on inclement weather. If there will be minimal sun, Way and Caple need to cautiously manage their use of power, as all their power is generated by solar. Also, the couple needs to be alerted to upcoming weather forecasts for preparation in case of a hurricane and challenging winds or waves. However, even if they’re alerted to rough weather ahead it will be difficult to change course far enough to avoid it.

When they do encounter rough weather—which is likely given the majority of their trip falls smack dab in the middle of hurricane season—the plan is to hunker down. Way and Caple will tie down everything aboard and employ a para-anchor, an underwater parachute that creates drag to stabilize the boat, then wait out the storm in the cabin. The boat is designed to roll back up if flipped over.

But what if they’re faced with a hurricane? Way and Caple say that staying with the boat is the safest option for both them and any potential rescuers. When faced with severe weather, they will deploy the para-anchor, alert their shore team manager, and seatbelt themselves in the stern cabin. If in life-threatening trouble, they’ll be able to activate a distress signal from radio beacons on their life vests, which would be picked up by a satellite and then transmitted to search and rescue authorities.

They plan to leave any time this week when a five-day stretch of decent weather will enable them to get to open sea safely. “In our society, it can be hard to even fathom stepping away from our office cubicles and daily routines,” says Way. “We want to show that it can be done—we want to inspire people to get out and do something great.”

You can track the team’s progress on their website and blog, 1000Leagues.com, which they will update by satellite.

New Survey Shows AMS Members' Positions on Climate Change

The vast majority of members of the American Meteorological Society agree that recent climate change stems at least in part from human causes, and the agreement has been growing significantly in the last five years.

According to a new survey of AMS members, 67% say climate change over the last 50 years is mostly to entirely caused by human activity, and more than 4 in 5 respondents attributed at least some of the climate change to human activity.

Only 5% said that climate change was “largely or entirely” due to natural events (while 6% said they “didn’t know.”)

The findings are from the initial results of a 2016 national survey of more than 4,000 AMS members just released today by George Mason University. The joint GMU/AMS study was conducted in January with support from the National Science Foundation.

Four in five respondents say their opinion on the issue has not changed over the last five years, but of the 17% who did shift, 87% said they feel “more convinced” now that human-caused climate change is happening. Two-thirds of them based this change on new scientific information in the peer-reviewed scientific literature, although in general respondents report basing these changes on multiple sources of information, such as peers and personal observation. Indeed, 74% think that their local climate has changed in the past 50 years.

AMS membership is largely constituted of professionals in the weather, water, and climate fields. One-third of the respondents hold a Ph.D. in meteorology or the atmospheric sciences, and overall just more than half have doctorates in some field.

Yet, while highly educated, the AMS membership represents a different selection of the profession than the climate-expert community commonly cited in statistics about the scientific consensus on climate change. Only 37% of AMS respondents self-identified themselves as climate change experts.

As a result, despite the growing agreement among the membership, there are differences in the results of the new survey compared to the position of climate scientists reflected in the reports of the IPCC.

On one key basic point the difference between the climate expert community and the AMS community as a whole is nearly negligible: AMS members are nearly unanimous (96%) in thinking that climate change is occurring and almost 9 in 10 of them are either “extremely” or “very” sure of this change. Only 1% say climate change is not happening.

However, the AMS Statement on Climate Change, which basically reflects the IPCC findings, not only says “warming of the climate system now is unequivocal” but also says, “It is clear from extensive scientific evidence that the dominant cause of the rapid change in climate of the past half century is human-induced increases in the amount of atmospheric greenhouse gases.” The new survey shows the AMS community as a whole is still moving toward this state of the science position. Furthermore, the new GMU/AMS survey does not probe members’ views on specific mechanisms of human-caused climate change.

Full results of the survey, including what members think of the future prospects for climate change, are posted here.

Milestones for the AMS Education Program

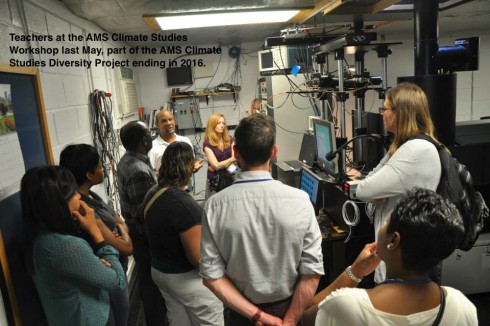

In a milestone year for the now 25-year-old AMS Education Program, one of the proudest achievements was the successful completion of the five-year AMS Climate Studies Diversity Project. This NSF-funded initiative introduced and enhanced geoscience and/or sustainability teaching at nearly 100 minority-serving institutions (MSIs) since 2011.

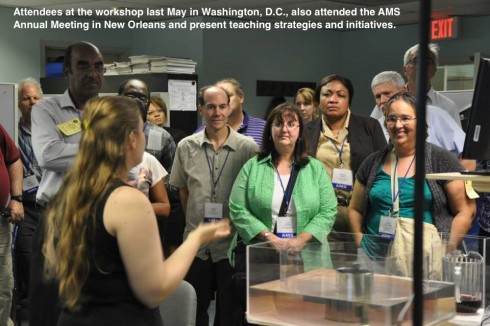

The recent AMS Annual Meeting in New Orleans was the final event in the project; it included a Sunday workshop bringing together 18 faculty from minority-serving institutions who had attended the project’s May 2015 workshop on implementing the AMS Climate Studies course. The faculty not only attend the workshop; they also presented at the subsequent Education Symposium of the Annual Meeting.

Overall in the Climate Studies Diversity Project, AMS was able to partner with Second Nature, a nonprofit working toward societal sustainability through a network of colleges and universities, to recruit 101 faculty to attend Climate Studies workshops in Washington, D.C. to learn from top scientists at Howard University, NOAA, and NASA. The attendees then incorporated the AMS Climate Studies course materials, real-time data, and lessons in their teaching.

Since 2001, in faculty enhancement through the AMS Weather Studies and Ocean Studies courses and now the Climate Studies Diversity Project, AMS has engaged 24,000 students through 220 MSIs.

Two of the MSI faculty who presented their climate science teaching in New Orleans shared with The Front Page blog their impressions of the May 2015 AMS Climate Studies Course Implementation Workshop:

Ivetta Abramyan, Professor, Florida State College at Jacksonville:

The combination of noteworthy speakers and fascinating field trips made the workshop a very informative and engaging environment and I found myself absorbing a plethora of information. Upon walking out of our meeting room on the last day, I realized that I not only gained a wealth of knowledge on a variety of climate-related topics, but also gained a support system that I will hopefully have for the rest of my career.

We were armed with valuable resources to help us tackle the challenge of teaching a brand new course or incorporating new material into existing courses. I learned about so many new websites, programs, initiatives, and funding opportunities. The field trips to NCEP, the Beltsville Center for Climate System Observation (BCCSO), and NASA Goddard provided an opportunity to see the operational side of the field. They were inspirational and motivating to say the least. In fact, I had a student email me a few days later asking for some ocean data. It felt good to be able to direct him to one of the NOAA Ocean Prediction Center sites that was shown to us during the NCEP tour.

In addition to the arsenal of tools and resources we were given, the workshop provided indispensable insight and sense of community. There were quite a few quotes that left an impression on me, some of them being: “We did not get out of the Stone Age because we ran out of stones,” by Rear Admiral David Titley, and “every state is an ocean state.” However, the one that really resonated with me was from Frank Niepold, the Climate Education Coordinator at NOAA’s Climate Program Office, who mentioned that students are getting the majority of their climate information from unskilled, unreliable, nonscientific sources. That statement is overwhelmingly true, and it made me realize just how much of an impact we, as educators, can potentially have on our students.

Another aspect of the workshop that I found intriguing was the diversity among the faculty in attendance. So many different institutions were represented, both large and small. The faculty also had various educational backgrounds. Our group of approximately 30 professors consisted of meteorologists, geologists, oceanographers, biologists, geographers, and everything in between.

Regional differences were also very evident. For example, I teach on a campus that is approximately nine minutes from the coast, and found it fascinating that other workshop attendees and fellow colleagues have classes in which the majority of students had never been on a boat. These conversations sparked ideas for collaboration projects within the cohort and we were excited to present our results at the AMS Annual Meeting. The connections we made at the workshop can be just as important as content in making us effective leaders in an effort to help change the world with respect to climate education.

On a more personal note, it can be a challenge for minority serving institutions to encourage their student body to pursue the STEM fields. The Earth science and physical science majors are extremely underrepresented in our population. We have few traditional students. My students range in age from 16 to 66. Some have full-time jobs. Some have families. Some are active military. Although they have the same drive, aptitude, and interests as traditional students, they may not have the resources. Many of them have academic dreams, but don’t know what opportunities exist. They don’t realize that NASA, NSF or other federal agencies would be willing to fund them if they were to pursue those dreams. They may be interested in the atmosphere or the oceans, but lack the motivation or confidence to make it a career path. It could be something as minor as not having the right information. Some of these students have a potential fire within and it is up to us to provide the spark to truly make them shine. We are on the front lines, not just for climate education, but STEM disciplines in general. Our voice is the bridge between can’t and absolutely can and I truly feel like the AMS Climate Diversity Project Workshop helped strengthen that voice.

In fact, as I was writing this, I received another email from the aforementioned student that I gave the OPC link to. He is declaring that he wants to change his major to a physical science and wants to meet to discuss his options. This student also happens to be a minority. It’s pretty rewarding to see the impact that this workshop is already having before the course has even been taught. I hope to utilize everything I learned during that week to inspire my students the way that the workshop inspired me.

María Calixta Ortiz, MSEM, (PhDc), Associate professor, Universidad Metropolitana, San Juan Puerto Rico:

One of the best decisions I have made was to apply for an announcement from Second Nature inviting professors to be part of the Climate Diversity Project from the American Meteorological Society. Our climatology course, which I have not taught, had not incorporated climate change. I was searching for more experience with climate change to integrate it to the curriculum at my school.

Climate change has mixed meanings for students living in an island in the Caribbean. Most of the time, students underestimate and misunderstand the topic, mainly because it is seen as a future event, and because models have many uncertainties. Traditionally, water sources in Puerto Rico have been considered vast and sufficient for all purposes. However, this availability could be impacted by future challenges of climate change. Puerto Rico has experienced climate variability in terms of alternated extremely heavy precipitation in some areas and droughts in other areas that have driven potable water rationing.

In addition, being an island, 67% of the population lives in coastal municipalities. Demand for the occupation of coastal land increased 25% over the period 2000-2005. The amount of population living in coastal areas signalled a challenge for policymakers and environmental planners.Change and climate variability combined with social, economic, and environmental factors produce synergistic effects on human health. Climate change is definitely a threat to human health, so “it is about people.”

As the dean of the school, my AMS experience will help me in different ways to update the curriculum. First, I intend to include knowledge and evidence on climate change—NOAA data, NASA simulations, and current references—as part of the course of climatology. Then, we will include the topic in related courses: environmental science, Earth science, and oceanography. Finally, when I feel comfortable with the topic, I will teach the course of climatology myself.

In the future, the school can move to consider a master degree in climate studies focused on preparing the population for mitigation and adaptation. We are responsible for preparing professionals for building resilience within communities, and to develop leaders who will have the ability to cope with external perturbations to society and its infrastructure caused by climate variability. More students need to understand Earth’s climate system and the evidence of climate change to evaluate potential impacts on human health and to improve the decision-making process.

2015: The Hottest Hiatus

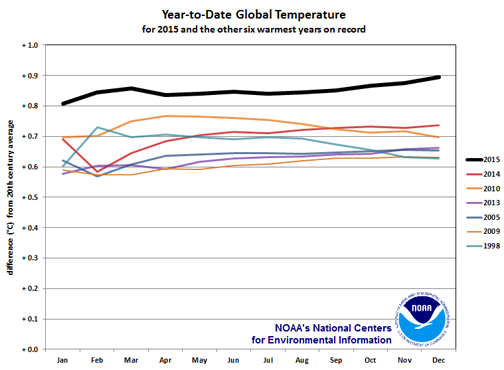

It was predicted early and often—and now, finally, it’s official. Throughout 2015, climate-watchers at NOAA and NASA were giving indications that the world’s surface temperature was going to top every annual mean measured since records began in 1880. Today, the two agencies with independent analyses jointly confirmed that global surface temperatures in 2015 blew away the record set in 2014.

The mean global temperature in the analysis by NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies was 0.13°C above the 2014 record, and NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information had it as 0.16°C above. In all, according to NCEI, 2015 was 0.90°C above the 20th-century average.

The temperature record was no surprise, even though 2015 set a new record by the largest margin ever recorded. In the horse race of annual temperatures, 2015 jumped out of the gate ahead of the pack and never looked back at previous record holders like 1997, 2005, and 2014 (see the NOAA graphic below). It was a wire-to-wire victory in which 10 of 12 months were the hottest ever on record for their respective periods. Indeed, going into the homestretch, NCEI pointed out that December 2015 would have to stumble to more than 0.81°C below average to avoid setting a record. Instead, December extended the year’s lead by registering 1.11°C above the 1880-2015 century average—in other words, it was the hottest month in the century-plus of measurement history.

Inevitably, the question arises: does this record conflict with the notion of a “hiatus,” which the IPCC addressed in its Fifth Assessment Report in 2013? Trend aside, 15 of the 16 hottest years on record have occurred in this still-young 21st century, according to NASA; NOAA says four different years in that brief period have now reset the global surface temperature record.

Not surprisingly, a decade or so is a mere blip in climatology terms, and the short-term trend of global warming depends on where you mark the start and end point of your analysis. The warming has been relatively fast since 1970—about 0.16 or 0.17°C per decade, depending on your dataset. If you just look at only 1998-2012, as IPCC did, during sustained warmth near record levels, the upward trend is half what it is over the longer period. Of course, starting with 1998 means starting out very warm—hence a trend with major handicapping.

As a result, there’s been scientific backlash against use of the term “hiatus.” As Stephan Lewandowsky, James Risbey, and Naomi Oreskes point out in a newly released article in BAMS, the word doesn’t fit:

The meaning of the terms “pause” and “hiatus” implies that the normal fluctuations in warming rate have been surpassed such that warming has stopped.

They show that warming looks slower or faster depending on the start date of any given 15-year period, but that none of the slowest-warming periods, including the last 15 years, is any slower than one might expect in a warming climate post-1970 (or indeed less remarkable with longer periods one might choose). They conclude,

The “pause” is not unusual or extraordinary relative to other fluctuations and it does not stand out in any meaningful statistical sense.

Lewandowsky and colleagues go on to show that, objectively, “hiatus” doesn’t pass the eye test. When tested by looking at a curve resembling the global temperature curve, experts and nonexperts alike perceived a long-term, uninterrupted upward trend. The authors conclude that misuse of the word “hiatus” distorts how the data look, and thus impedes not only public perception of global warming but also scientific work.

One benefit of the “hiatus” talk is that scientists have been motivated to ask more questions about the normal short-term fluctuations of climate. One purpose of the Community Earth System Model’s Large Ensemble Project, for example, is to produce large numbers of climate model simulations to help “disentangle” model error from internal climate variability—that is, the fluctuations caused by climate irrespective of anthropogenic forcing.

In an article in the August issue of BAMS, the ensemble project’s investigators show a sample experiment in which the slower warming of the last 15 years has actually been a pace well within normal variability, with or without greenhouse gas forcing (see figure below).

As the world continues to warm, this year’s record is prone to fall. Meanwhile, the ensemble also shows that the odds of a 10- or 20-year fluctuation stopping the warming—let alone a brief cooling—keeps getting tinier and tinier.