Often our Annual Meeting week feels like a chance to get away from some of the day-to-day issues of work to focus on exchanging scientific ideas with colleagues. This year, the AMS Annual Meeting is a virtual gathering, however, so there’s little chance  any of us will escape entirely the everyday concerns of COVID-19 this week, whether it was the subject of research, a challenge to providing services, performing community engagement, educating future scientists, or even if it meant impacts on the world that obscured research results in other topics. The meeting programming itself is an indication that no scientific aspect of 2020 escaped the pandemic entirely. In fact, this is a good week to catch up on how the pandemic has impacted the weather, water, and climate enterprise in 2020, if you to want to navigate the Annual Meeting and hop through the conference schedules to look for pandemic-related topics. Some of these presentations are most obviously found in the Conference on Environment and Health, but in other conferences too. Below, we’ll give you some suggestions for following up on this unavoidable intersection of science and society . Meanwhile, keep it virtual, and be safe and healthy. After all, that’s one reason this is unlike any other AMS meeting week.

any of us will escape entirely the everyday concerns of COVID-19 this week, whether it was the subject of research, a challenge to providing services, performing community engagement, educating future scientists, or even if it meant impacts on the world that obscured research results in other topics. The meeting programming itself is an indication that no scientific aspect of 2020 escaped the pandemic entirely. In fact, this is a good week to catch up on how the pandemic has impacted the weather, water, and climate enterprise in 2020, if you to want to navigate the Annual Meeting and hop through the conference schedules to look for pandemic-related topics. Some of these presentations are most obviously found in the Conference on Environment and Health, but in other conferences too. Below, we’ll give you some suggestions for following up on this unavoidable intersection of science and society . Meanwhile, keep it virtual, and be safe and healthy. After all, that’s one reason this is unlike any other AMS meeting week.

The Pandemic Impact on the Global Earth Observing System and Forecasting Operations and Research Programs

In the Conference on Aviation, Range, and Aerospace Meteorology, Blake Sorenson (Univ. North Dakota) et al. discuss “Regional Impacts of Aircraft Observation Losses Caused by the COVID-19 Pandemic.” They point out:

Thousands of commercial aircraft in the United States and around the world provide meteorological observations every day, obtaining valuable measurements of temperature, wind, and (from a subset of aircraft) humidity. These aircraft are a critical source of upper-air observations for operational numerical weather prediction, especially over regions with limited radiosonde coverage such as the tropics and southern hemisphere. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, many airlines from around the world saw drastic decreases in flight activity, with portions of Europe seeing a near complete loss. The decrease in flights from January 2020 to April 2020 also resulted in a significant loss in aircraft observations, which is noticeable in both aircraft observation counts and Forecast Sensitivity to Observation Impact (FSOI), which is a measure of error reduction in 24-hr forecasts from a specific group of observations. In January 2020, aircraft observations accounted for 5.7% of the total number of observations assimilated into the U.S. Navy’s Navy Global Environmental Model (NAVGEM) and accounted for 9.5% of the total error reduction. In April 2020, aircraft obs accounted for only 2.2% of the total ob counts and 4.2% of the total error reduction. Interestingly, the total FSOI was nearly the same in the two months, which implies that the beneficial impact of the other observation types increased.

While the aircraft observations in the Northern Hemisphere dropped by nearly 50% from January 2020 to April 2020, the amount of error reduction due to aircraft obs at those latitudes only slightly decreased. Aircraft observation counts in the Southern Hemisphere and tropics dropped by nearly 100% and the error reduction from the aircraft ob group decreased almost completely, reflecting the importance of aircraft observations in data-sparse regions. This presentation will expand on the global FSOI statistics and delve into regional statistics of the changes caused by decreases in aircraft observations from the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic to the later stages of the pandemic, especially for South America, Australia and New Zealand, East Asia, Europe, and CONUS. The impacts of aircraft observation losses on FSOI in data rich areas will be contrasted with the impacts in data sparse areas.

Similarly, and also at the same conference, Eric P. James (CIRES) et al. present on “Commercial Aircraft-Based Weather Observations for NWP: Global Coverage, Data Impacts, and COVID-19.” They write:

Weather observations from commercial aircraft have been shown to be the most valuable observation source for short-range numerical weather prediction (NWP) systems over North America. However, the distribution of aircraft observations is highly irregular in space and time. In this study, we summarize the recent coverage of aircraft observations over the globe, and provide an updated quantification of their impact upon short-range NWP forecast skill. Aircraft observation coverage is most dense over the contiguous United States and Europe, with secondary maxima in East Asia and Australia / New Zealand. As of late November 2019, 665 airports around the world had at least one daily ascent or descent profile of observations; 400 of these come from North American or European airports. Flight reductions related to the COVID-19 pandemic have led to a 75% reduction in aircraft observations globally as of late April 2020.

A set of data denial experiments with the latest version of the Rapid Refresh NWP system for recent summer and winter periods quantifies the statistically significant positive forecast impacts of assimilating aircraft observations. Additional experiments excluding approximately 75% of aircraft observations reveal a statistically significant degradation of forecast skill for both winter and summer seasons; these results provide an approximate quantification of the short-range NWP impact of COVID-19 related commercial flight reductions, demonstrating that regional NWP guidance is degraded due to the availability of fewer observations. This finding further highlights the importance of aircraft observations for regional NWP data assimilation.

In the Conference on Atmospheric Chemistry, Laura L. Pan (NCAR) et al. note in a presentation on the airborne field program, The Asian Summer Monsoon Chemical and Climate Impact Project (ACCLIP), deployments of aircraft over the western Pacific were postponed from 2020 to 2021 due to the pandemic but “the positive side of the delay has been the opportunity to perform more extensive pre-campaign studies.”

The Pandemic Impact on the Earth System

In Friday’s sessions of Major Weather Events and Impacts of 2020, Paul Miller et al. (Louisiana State Univ.) report on how “China’s COVID-19 Quarantine Marginally Exacerbated a Warm February 2020.” They write:

In the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, east China experienced two consecutive months of exceptionally warm weather, with 28 cities observing their warmest January-February period on record. Coincident with these unseasonable temperatures, large areas of China faced restricted economic activity due to COVID-19 quarantines, which were subsequently associated with marked air pollution reductions. Because particulate pollutants can scatter, diffuse, and absorb incoming solar radiation, serving as net negative radiative forcing, a reduction in air pollution can yield warming at the surface. This study explores whether the warm February 2020 in east China was exacerbated by COVID-19 quarantines. [Insights from modeling show] The C19Q emissions reductions increased surface air temperatures, with warming concentrated in interior China due to the synoptic circulation pattern. A maximum temperature increase of 0.13°C was observed in Changde, roughly 300 km west of Wuhan. In contrast, warming was not observed over the haze-prone North China Plain, where mean northwest flow dispersed pollution offshore in both emissions scenarios. Though a seemingly minor increase in temperature, epidemiological research suggests marginal warming may have a non-trivial effect on SARS-CoV-2 transmission, especially when integrated over densely populated regions such as east China.

The shutdowns aimed at preventing the spread of COVID had measurable impacts on the atmosphere and air quality during 2020. So many (but not all) of these presentations are in sessions of the Conference on Atmospheric Chemistry.

In the Symposium of Lidar Atmospheric Applications, Simone Lolli (SSAI, and National Research Council, Tito, Italy) et al. present “Effects of the Lockdown Imposed by the COVID-19 Pandemic on Vertically Resolved Aerosol Profiles Assessed through Different Permanent Observational Sites of the NASA MPLNET Lidar Network.”

In the Conference on Atmospheric Chemistry, Qiyang Yan (Georgia Tech) et al. present a poster on, “Satellite observed reduction of nitrogen oxides emissions during the COVID-19 pandemic and its impacts over the United States.” Their discussion:

In response to the COVID-19 global pandemic, the state and local governments declared emergency and enforced lockdowns to slow the progress of infections in March 2020, which significantly reduced pollutant emissions in the United States. Satellite observations of nitrogen dioxide (NO2) have been used to estimate nitrogen oxides (NOx) emissions due to COVID-19 We monitored emission changes over the U.S. in correspondence to the enactments of varied virus control policies and social behavior changes in different states. The effects of NOx emission changes on surface ozone and the oxidation state of the boundary layer in the U.S. are assessed to evaluate the environmental impacts of COVID-19. The NOx emission changes are also applied in a Susceptible-Exposed-Infectious-Removed model to understand the values of satellite observations on the management of public health crises.

Similarly, in another session on air quality in the Conference on Atmospheric Chemistry for example, Doyeon Ahn (Univ of Maryland, College Park) et al. present on “Reduced Emissions of CO2 and NOx from Power Plants in the Eastern United States during the COVID-19 Pandemic Period: Separating the Impact of COVID-19 against Varying Weather and Fuel-Mix.” In part their abstract states:

During the COVID-19 pandemic period, electricity generation patterns in the United States were disrupted as people have spent more time at home while commercial and industrial activities were reduced. Reductions in electricity generation associated with decreased demand led to declines in emissions of air pollutants from power plants. In this study, we estimate the reduction in the emissions of CO2 and NOx from power plants in Eastern U.S. we estimate the “Business-as-usual (BAU)” gross electric outputs in Eastern U.S.: i.e., the likely gross electric outputs given the weather conditions and historical trend in fuel-mix usage without COVID-19. Then, we estimate the BAU emissions of CO2 and NOx during COVID-19 pandemic period. Preliminary results show that power plant emissions of CO2 and NOx were reduced most significantly in April 2020, with following months showing varying magnitudes of reduction. The relative magnitude of reduced emissions from power plants in Eastern U.S. will be compared to reduced emissions from transportation sector during Spring 2020.

Also at the same conference, Alexander Kotsakis (NASA Goddard) et al. present “Analyzing the Impact of COVID-19 on tropospheric NO2 Using Pandora observations across North America“:

As the primary precursor to ozone production, NO2 exhibits large amounts of heterogeneity on vertical and horizontal scales. The well documented decreases in NO2 pollution from pandemic shutdowns worldwide are seen in daily satellite observations. While satellite observations of NO2 from polar orbiting satellites (TROPOMI, OMI, etc) provide a unique high resolution spatial perspective, these satellites only provide a once daily snapshot. Pandora, a ground based spectrophotometer, allows us to measure column NO2 at a much higher temporal resolution that is on a similar scale to that of a traditional in-situ surface NO2 monitor. To quantify the changes in NO2 due to COVID19 from a ground based perspective, we utilize a combination of Pandora and in situ observations to investigate the changes in surface and column NO2. Using the combination of these observations we will provide better insight into changes in the diurnal variation of NO2. The results of this study are essential for understanding the sensitivity of column measurements to emission changes and for better interpreting future geostationary air quality observations.

Going the Other Way: The Effect of the Atmosphere on the Pandemic

While COVID impacted the atmosphere especially through societal changes, the weather, as expected in epidemiological models, impacted the outbreak itself.

In the Conference on Environment and Health, Beatriz Hervella (AEMET, Spanish Meteorological Agency) presents on the “Impact of Temperature on the Early Dynamics of the COVID-19 Outbreak in Spain.” She notes:

The role played by the weather in the outbreaks of the Covid-19 pandemic is being discussed and is still highly uncertain. There are studies that suggest that meteorology is only a minor factor in the evolution of the pandemic, once it has already started, compared to other more relevant factors such as policy measures, the lack of population immunity, social factors as human density, public transport, social habits or the evolutionary dynamics of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus itself. But what about initial pandemic stage of an emerging pathogen? Within the same country with the same cultural aspects and containment policies (without lockdown), why did the disease evolve exponentially in some areas while in others it did not?

Our hypothesis is that the weather is a relevant factor in this first stage of spread, favoring the development of this new virus for the population in some areas against others; it is in line with previous studies that point out cities with significant outbreaks of COVID-19 have very similar climates pattern with relatively cool and dry environment . In order to proof it, the covid-19 trigger incidence rate has been calculated, defined as the critical time for the onset of the epidemic spread, in each of the 50 Spanish provinces. Analysis has conducted to explore the association between this incidence rate and the average temperature over 14 and 7 days in order to take into account the covid-19 incubation period (the average incubation period is 5–6 days with the longest incubation period of 14 days. When the epidemic explodes, we have found an average temperature threshold below which the provinces have developed the most several outbreaks. Consequently, above it, the spread has been much milder or less relevant; in Spain it seems that the virus has harder time spreading in warmer temperatures.

The results that have been obtained may be useful in the future because when population immunity would be obtained and if the disease becomes endemic, meteorological factors will play a fundamental role again.

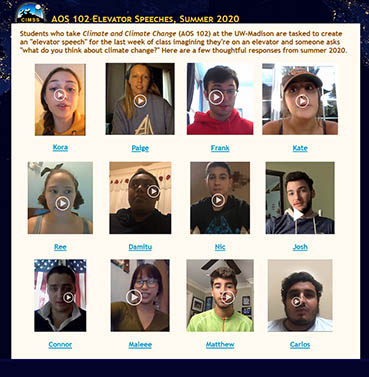

Education During a Pandemic

In the poster session of Sunday’s 20th Student Conference, Joshua Higgins et al., all with the University of Alabama-Huntsville, present on the COVID adaptations made to continue UAH’s “unique leadership and active-learning opportunities for undergraduates in the Department of Atmospheric and Earth Science as members of the student organization UPSTORM – the UAH Profile Sounding Team for Operational and Research Meteorology.” They continue:

UPSTORM is a necessary component of meteorological research and upper-air analysis for the National Weather Service (NWS)…. Safety is always UPSTORM’s number-one priority, and the existence of the Coronavirus Pandemic has strengthened that prerogative. The presence of COVID-19 has changed the way training is conducted, with a limited number of students able to be trained at a given time, all while wearing masks and adhering to social distancing guidelines. Although COVID-19 has altered the way operations are completed, each member continues to undergo training each semester on the preparation involved to launch weather balloons, Python and SHARPpy use, and the set-up process of several data collection instruments used in the field.

At the Conference on Education, Tiffany Fourment (UCAR) et al. present a poster entitled “Turn and Face the Strange: Lessons Learned for Digital K-12 Education in Changing Times.” They write:

The School and Public Programs team at the UCAR Center for Science Education implements K-12 field trips, public tours, and outreach events at the National Center for Atmospheric Research Mesa Lab.

In March 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic turned our daily lives and work upside down, we were forced to pivot abruptly in a number of ways. In the following months our team scrambled to shift our focus from in-person to online programming. This process called for a dynamic combination of flexibility, new skill acquisition, candid analysis of our team’s strengths and challenges, humility, and good old-fashioned trial and error (in fact, it still does today). It has resulted in a number of digital learning resources and opportunities for K-12 educators and students including live virtual activities, recorded videos with supplemental resources, and “Meet the Experts”—a series of presentations and Q&A with subject matter experts.

Nobody would ask for the challenges introduced by the pandemic, but we can appreciate that it pushed us to work on something we had been discussing for some time: developing digital education programming for K-12 students, teachers, and the general public. While this effort was instigated by a major global catastrophe, the outcome will prevail and evolve as we define our “new normal”. Our programming abilities have expanded, allowing us to reach more diverse and widespread audiences than we have in the past.

This presentation will detail the learning process that accompanied our shift from in-person to digital K-12 education programming, what worked and what didn’t, and the vision for sustaining our programs through whatever future changes may come.

Also in the Conference on Education, Valerie Sloan (NCAR) et al. write about lessons learned from student internships in the tumultuous summer of 2020:

Undergraduate students faced a challenging summer in which many missed out on summer research opportunities due to COVID-19-related cancellations. Some internships did proceed, with most running remotely and a few on-site. Unprecedented conditions faced this year’s cohort. This included living and working under the difficult conditions of the pandemic and witnessing the heightened police violence against people in the Black community. Puerto Rican students were also faced with earthquakes, a tropical storm, and an unpredictable power supply. In this presentation, students who participated in online REU experiences will discuss the challenges and successes of working remotely within this period of history. They will identify those strategies that promoted a sense of engagement and community, and effective mentoring. They will also discuss ways to support students in dealing with traumatic current events. The successful engagement through remote internships this summer suggests that virtual programs prepare students to face new work environments, as conferences, courses, and collaborations continue to shift online. These may come to attract a broader range of students than those who have participated in the past. It is our hope that it will result in more equitable, accessible opportunities for students pursuing geoscience careers.

And again in the Education Conference, K. Ryder Fox (Univeristy of Miami, Florida) et al. note in a poster that COVID exacerbated the ongoing mental health crisis in amongst STEM grad students, and especially heightens the need for interventions for marginalized STEM Individuals. They write:

… many marginalized individuals face greater personal crises, including greater health risks, as well as job, food, and home insecurity. The mental health crisis within STEM fields has been compounded by increased isolation, disrupted research and coursework, national discussions of police brutality and racial inequality, and living in unprecedented times of uncertainty.

We employ a radical approach of creating the first 24/7 text-based crisis hotline run by and for marginalized individuals in STEM.

Adapting and Enhancing Services during COVID

The meeting provides numerous examples of how the atmospheric science community had to work quickly to respond to the COVID challenges by enhancing products in all sorts of settings. Many scientists found COVID increased the need for applications of earth systems information and forecasts.

In the Symposium on Societal Applications, for example, Michael Brewer (NESDIS) et al. report on “The Value of Environmental Data from NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information.” Their abstract states:

For over 6 years, NCEI has systematically documented the interactions it has had with users. Information from over 70,000 users has led to an understanding of the uses and benefits that NCEI information provides to every sector of the US Economy. These user insights have also been used to drive products and services changes across NCEI’s product portfolio. This talk will focus on the product changes and benefits received, with an emphasis on the value NCEI has played in the current COVID-19 Pandemic response and understanding the spread of coronavirus. It will also highlight the need for a systematic approach to insights from bulk users that would provide critical understanding of how NCEI can make its products and services more valuable. This presentation will also summarize mechanisms NCEI uses and will use in the future to document the value of its information.

Brewer and student scholar Alexandra Grayson present a related poster in the Sunday sessions, “Applications of NOAA’s Environmental Data to Emerging Real-time Crises: A COVID-19, Public Health and Climate Solutions Example.” In it they state:

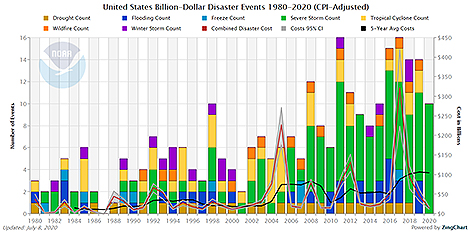

The Coronavirus pandemic has highlighted the application of NOAA’s climate information to researchers and decision-makers in the public health sector. This paper focuses on the impact that NCEI has had in providing climate information to those seeking to better understand the COVID-19 respiratory virus and the way it may be impacted by environmental parameters. The paper then addresses NCEI emerging activities related to COVID-19 and wildfire smoke data, wildfire responders’ health, and Western wildfire evacuation planning.

In the Conference on Environment and Health, Raymond B. Kiess (AWS) et al. present on “Creating Actionable Climate Intelligence and Communicating Uncertainty during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” They write:

The onset of the Covid-19 pandemic produced a wave of research investigating the potential impact of weather and climate on the spread of the novel coronavirus. As the Air Force’s authoritative provider of climate intelligence, the 14th Weather Squadron (14 WS) was charged with distilling the dynamically evolving body of research into products to inform Department of Defense (DoD) and National Intelligence Community (NIC) risk assessments. In this presentation, we outline how 14 WS leveraged medical research and interagency partnerships to produce tailored, actionable climate intelligence at the speed of relevance while at the same time communicating the uncertainty and limitations associated with emerging research.

Early in the pandemic, media coverage of research highlighting the similarities between weather conditions in the areas of initial Covid-19 spread motivated inquiries to the 14 WS. In response, 14 WS conducted an initial literature review focusing on temperature and humidity ranges that were associated with higher rates of Covid-19 transmission. Coordination with Air Force Weather colleagues and the Air Force’s Surgeon General Office was necessary to establish confidence and appropriately communicate uncertainty. Initial products showed when and where the temperature and humidity ranges associated with increased Covid-19 transmission occur on average globally, regionally, and locally. As research evolved, 14 WS updated and added products to reflect the current state of the science. Updates included the development of Ultraviolet Index climatology products and modeled risk metrics. Throughout the process, 14 WS accompanied product releases with caveat statements and explanatory documents to communicate uncertainty and help users accurately interpret tailored products….14 WS created map-based decision aids that identify the regions most at risk from environmental hazards such as tropical cyclones, tornadoes, floods, wildfire, and winter weather by month. These climatology-based products enable readiness by identifying risk windows with lead times sufficient to allow proactive preparation. 14 WS staged all climatology products relevant to the pandemic on a tailored webpage specifically built to deliver climate intelligence to inform the DoD and NIC response to Covid-19.…The speed of operations required products to be created and communicated as research became available “at the speed of relevance;” before the peer review process could be completed. This required 14 WS to be agile, iterating and adjusting as research evolved, and rely on interagency coordination to access medical and epidemiological expertise not organic to the unit. In addition, clear communication was critical to ensure that end users understood how to interpret climate intelligence to inform operations in the context of Covid-19 and, importantly, the limitations resulting from using products as research was rapidly evolving. The lessons learned from the Covid-19 pandemic will be applicable to other climate intelligence applications moving forward.

Albert Martis (WMO) et al. will present at the Conference on Environment and Health on “Forecasting Healthcare Capacity By Using the Mass Curve Technique.” They state in their abstract:

An Empirical Model was developed to predict shape of the COVID-19 curve a week after a COVID-19 outbreak. To initialize the model the daily new cases were fitted to an exponential function with an initial growth factor. Historical COVID-19 data of several countries like China, Italy Spain France and Austria were used to estimate the governmental intervention index that can change the growth factor. Social Distancing, school closure, curfew or lockdown are among the intervention taken by the governments. This Empirical Model was tested with the outbreak of the COVID-19 and the government interventions in the Netherlands successfully.

This model can assess the behavior of the curve after the outbreak based on the governmental intervention and can be tool for decision making to monitor the compliance of the governmental measures and indicate the time for further escalation or de-escalation. Furthermore by using the mass curve technique, a widely used method in climatology, the healthcare capacity can be determine and the capacity of the IC.

In the Conference on Environmental Information Processing Technologies, Charles D. Camp (NWS) and Parks Camp (NWS) present on “Using Cloud-Based GIS Solutions to Rapidly Develop and Deploy an IDSS Interface during a Pandemic.” They write that …

Translation of data into actionable information is one of many critical steps successful completion of…Impact-based Decision Support Services (IDSS) …To ensure successful completion of this IDSS mission, which can be further complicated by a variety of factors, most notably the sheer amount of information to be shared across a variety of communication platforms. The COVID-19 pandemic of 2020 further exacerbated this challenge as National Weather Service core partners at the federal, state, and local levels were presented with additional weather-related threats to life and property as mobile testing sites, triage centers, and other types of healthcare facilities became of utmost importance. As a result, National Weather Service meteorologists were increasingly providing critical IDSS to core partners with the responsibilities of overseeing activities at these locations. It soon became evident that a more organized effort of cataloging and monitoring these IDSS locations was needed.

In response, a team of GIS subject matter experts across the National Weather Service’s Southern Region organized and charted a path toward a rapid prototype solution. … The result was a publicly viewable dashboard that was highly data driven, organized, flexible, and IDSS focused as it enhanced situational awareness and decision making capabilities for both the National Weather Service and its core partners.

Disaster Response in COVID and Other Pandemic Lessons and Impacts

In the Symposium on Building a Weather-Ready Nation, Craig Croskery (Mississippi State University) is presenting, “Learning from the COVID-19 Pandemic: When Public Health and Tornado Threats Converge.” He notes:

The pandemic also made the process of protecting individuals from tornadoes more challenging, especially when their personal residence lacks suitable shelter, particularly for residents of mobile homes. The necessity of having to shelter with other families – either in a public shelter or at another residence – in order to protect themselves from a tornado threat conflicted with the advice of public health officials who recommended avoiding public places and limiting contact with the public to minimize the spread of COVID-19. There was also a perception that protecting against one threat could amplify the other threat and a survey was undertaken with the public to determine the general viewpoint to see if that was indeed the case.

The results found that it was possible to attenuate both threats provided that careful planning and actions were undertaken. Understanding how emergency managers should react and plan for such dual threats are important to minimize the spread of COVID-19 while also maintaining the safety of the public…..both short-term and long-term recommendations were suggested which may also be useful…even after this pandemic is over.

In the Conference on Environment and Health, Yihan Wu (Harvard Univ.) et al. present on “the successes of mobility interventions in curbing the spread of the SARS-CoV-2, [which] demonstrate how policies can help limit the person-to-person interactions that are essential to infection.”

We investigate mobility changes during the first major quarantine period in the United States, assessing how human behavior changed in response to policies and to weather. We look at a variety of mobility metrics, including distance traveled, visitation rates to different destinations, and potential encounters measured based on proximity of mobile devices. We show that consistent national behavioral change was associated with clear national messaging and independent of local policy. Not only is the timing of mobility changes nationally consistent, potential encounters are related to distance traveled by an exponential relationship with a nationally consistent growth rate and a scaling directly proportional to population density. To explore the effect of weather on mobility, we high-pass filter both the weather and mobility time series and estimate their correlations and uncertainties using a bootstrapping technique. We find that while the number of park visitations changed with favorable weather conditions, generally the changes did not increase encounters between people. Experts predict this virus will continue to be a threat until a safe and effective vaccine has been developed and widely deployed; the independence of encounters and temperatures suggests that behavioral changes will not impact any direct physical modulation of transmission by weather as the virus becomes endemic. Both of these results are encouraging for the potential of the country to be able to curb the virus with clear national messaging.

The Symposium on Building a Weather-Ready Nation has many presentations with COVID-based lessons including in this joint session: “Hurricane Messaging: Improvements in Communicating Impacts, Uncertainty, and the Forecaster’s Decision-Making and Joint Session: Preparing for and Responding to Weather Events during the COVID-19 Pandemic,” including presentations on COVID adjustments for operations at NWS in Norman Oklahoma and for maintaining NWS Weather Forecast Office operations more generally.

In Sunday’s Student Conference posters, Delián Colón-Burgos (Pennsylvania State University) is presenting on “Hurricane Evacuations in the Age of COVID-19: How Evacuation Zones and Concerns about Location of Residence influence Perceptions of Risk and Evacuation Decisions.” The presentation recognizes COVID as “an urgent call to study the evacuation behaviors for this year’s hurricane season, due to conditions in shelters that may lead to further outbreaks.” They continue:

The purpose of this research is to understand the perceived and real risk factors that individuals consider in making evacuation decisions during a pandemic and see if these vary amongst people living in different evacuation zones and with different concerns about their location of residence. Data were obtained from an online statewide survey sent to Florida residents and analyzed using SPSS v26. Chi-square tests were performed between responses to four statements about anticipated evacuation decisions considering COVID-19 and a resident’s a) Evacuation zone (Ranging from Evacuation Zone A to non-Evacuation zones), b) Concerns about location of residence, and c) Water-based concerns. …It was found that a resident’s evacuation zone does impact their perceptions of risk for going to shelters regardless of the COVID-19 pandemic. Residents from high risk evacuation zones were found to be less likely to evacuate to a shelter, but at the same time less likely to shelter in place. Residents are hesitant of evacuating to a shelter due to possible close-quarters conditions that will lead to getting infected with COVID-19. These results can provide guidance to emergency management and local government in order to plan for this hurricane season with compounded risks.

The Rare Beneficial Effects

In the Conference on Environment and Health, Jan Null (San Jose State Univ.) and Andrew Grundstein (Univ. of Georgia) report that “After the two worst years on record in 2018 and 2019, the number of children that died inside hot vehicles in the United States dropped dramatically in 2020.” And they investigate “How and why might this be related to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.”

Another possible silver lining of the pandemic appears in the air quality sessions of the Conference on Atmospheric Chemistry. Julianna Christopoulos (NOAA) et al. present an “Assessment of COVID-19-Related Emission Changes on Crop Yields across the Continental United States.” Specifically they “estimate the losses/gains in soybean yields from the changed crop exposure to ground-level O3.” They write:

The pandemic’s impact on ground-level O3 is quantified using NOAA’s National Air Quality Forecasting Capability (NAQFC). The NAQFC simulations use ground- and satellite-based adjustments to the National Emission Inventory 2014 data that are projected for each state to the “would-be,” 2020 level business-as-usual (BAU) emissions, and compare this to a simulation that uses the actual COVID-19 (C19) emissions. The differences between the predicted O3 concentrations for the BAU and C19 cases are attributed to the economic slowdown impacts of the pandemic. The O3 changes caused by COVID-19 are then combined with a dose-response function and the soybean production for this year to estimate the losses/gains in soybean yields from the changed crop exposure to ground-level O3.

The Double Whammy: COVID and Social Justice Issues

The COVID path through the AMS Annual Meeting forms an intersection with one of the other salient societal issues of 2020: the inequities and social injustices that fueled the news in 2020 in the U.S. and that themselves form yet another pathway through the presentations of the Annual Meeting.

Here’s an obvious crossing of the two main societal themes that 2020 imparted on the 101st AMS Annual Meeting: the presentation at the Conference on Atmospheric Chemistry by Gaige Hunter Kerr, Daniel Goldberg, and Susan Anenberg (all of George Washington University): they write about the “Impact of Coronavirus Lockdowns on NO2: Successes and Challenges for Environmental Inequality in the United States,” and examine neighborhood-scale data on air quality beside demographic data to show that the largest reductions in NO2 during lockdowns occur in urban tracts whose populations are more racially and ethnically diverse and have lower household income and educational attainment:

While this result is promising given the environmental injustices that have long plagued disadvantaged communities, we find that even the dramatic reductions in NO2 during lockdowns are not large enough to decrease NO2 to the pre-pandemic levels experienced by tracts with higher income, higher levels of educational attainment, and fewer racial and ethnic minorities. To further understand the uneven gains in NO2, we also use traffic data and assess changes in mobility following lockdowns. This study highlights the potential for shrinking the gap in pollution exposure between population subgroups in the U.S. but simultaneously underscores the perennial challenges in reducing environmental inequalities. Our results may inform long-term policies aimed at reducing air pollution and associated public health damages associated with emissions from transportation and other combustion sources.

Check out our next blog post in this series if you’re interested in following this fork in the road  to a pathway of exploring the AMS Annual Meeting’s numerous crosscutting discussions of the relation of science and scientists to the equity, diversity and social justice issues which emerged as never before in the weather, water, and climate community in 2020 and dominated national news at the same time. It’s a natural and timely track to follow in this week’s meeting—just as the COVID track is—touching on numerous specialties, scientific issues, and interdisciplinary dilemmas.

to a pathway of exploring the AMS Annual Meeting’s numerous crosscutting discussions of the relation of science and scientists to the equity, diversity and social justice issues which emerged as never before in the weather, water, and climate community in 2020 and dominated national news at the same time. It’s a natural and timely track to follow in this week’s meeting—just as the COVID track is—touching on numerous specialties, scientific issues, and interdisciplinary dilemmas.

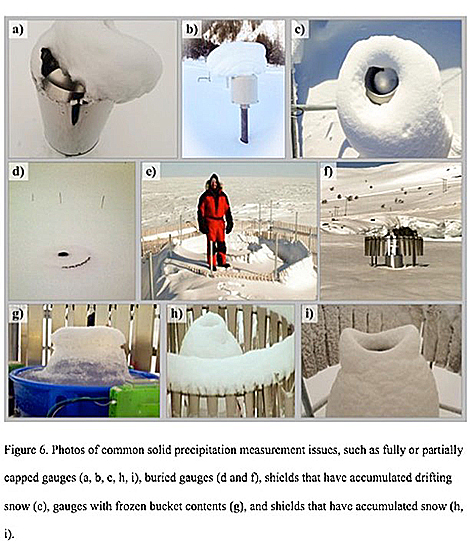

Meanwhile, Kochenderfer et al. note a proliferation of automated gauges and new non-catchment methods that involve using laser disdrometers and “present-weather” detectors to remotely determine what type of precipitation is falling.

Meanwhile, Kochenderfer et al. note a proliferation of automated gauges and new non-catchment methods that involve using laser disdrometers and “present-weather” detectors to remotely determine what type of precipitation is falling.

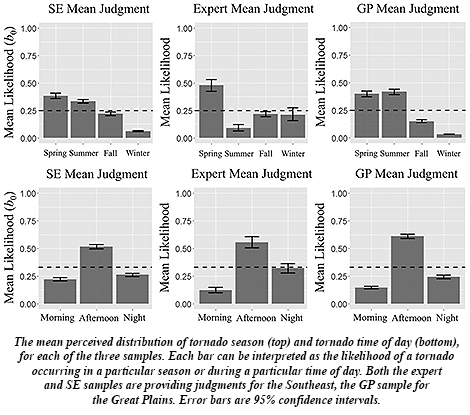

For starters, unlike in infamous “Tornado Alley” states of Texas and Oklahoma north through Nebraska and Iowa into South Dakota, the Southeast lacks a single, “traditional” tornado season, with tornadoes “spread out across different seasons,” Broomell along with his coauthors report, including wintertime. The Southeast also endures more tornadoes overnight, as happened last week in North Carolina. And they spawn from multiple types of storm systems in the Southeast, more so than in the Great Plains. This makes knowledge about residents’ regional tornado likelihood especially critical in Southeastern states.

For starters, unlike in infamous “Tornado Alley” states of Texas and Oklahoma north through Nebraska and Iowa into South Dakota, the Southeast lacks a single, “traditional” tornado season, with tornadoes “spread out across different seasons,” Broomell along with his coauthors report, including wintertime. The Southeast also endures more tornadoes overnight, as happened last week in North Carolina. And they spawn from multiple types of storm systems in the Southeast, more so than in the Great Plains. This makes knowledge about residents’ regional tornado likelihood especially critical in Southeastern states.