After a year of substantial social injustice-fueled upheavals, the 101st AMS Annual Meeting builds on social justice themes all week and you could make social justice the theme of you own virtual programming, picking and choosing your way through the sessions if you’re so inclined, right from the centerpiece Presidential Forum on Sunday, “Building a Culture of Anti-Racism in the Weather, Water and Climate Community.”

The session promises to be a frank conversation on racism and its impacts on the weather, water, and climate community. The panel will explore and discuss how racism against blacks, indigenous, people of color (BIPOC+) and other marginalized groups has not only denied opportunities to a wide range of people but also limited our ability to advance the weather, water and climate sciences and services. We will revisit our past and explore how even today social inequities are reflected in the provision of services to people living in underserved areas throughout the United States. The panel will discuss what actions have helped in combating racism, steps that have been taken to address social inequities in the provision of environmental services, and highlight steps we, as a community and individually, need to take to make further progress. AMS’s on-going activities in this area will also be highlighted.

Many presentations pick up on this keynote. Certainly, If you are interested in social justice issues, you will want to attend the Symposium on Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, which has valuable programming.

Addressing Social Justice within the Scientific Community

Session 8: “Advancing a Culture of Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility in the Geosciences” is the most inward looking of this key symposium in the social justice pathway through the AMS Annual Meeting—this session is a self-examination of these issues within the scientific community.

The Symposium is also holding a joint session with the Conference on Education: “The Dr. Janet Liou-Mark Memorial Session on Effective Strategies for Increasing Minority Participation in the Atmospheric Sciences.”

Also at the Conference on Education, Valerie Sloan (NCAR) et al. are presenting, “What Worked for Us? Student Experiences with Geoscience Summer Research Internships during Both COVID-19 and Heightened Racist Violence.” They write:

The successful engagement through remote internships this summer suggests that virtual programs prepare students to face new work environments, as conferences, courses, and collaborations continue to shift online. These may come to attract a broader range of students than those who have participated in the past. It is our hope that it will result in more equitable, accessible opportunities for students pursuing geoscience careers.

Session 1 of the Conference for Early Career Professionals invites attendees “to come together and create and experience inclusive environments—an improvscience workshop.” to explore simple, creative ways to cultivate diverse voices, equity, and inclusion.”

Also, there’s Town Hall Meeting—”Her Career, Her Stories“—from the 35th Conference on Hydrology:

This event will bring women of all career stages together to share experience, challenges, and success, to inspire and empower one another, and to foster the development of mentoring relationships. A diverse group of scientists will speak at the event as panelists, including Ana Barros, Terri Hogue, Ruby Lai-Yung Leung, Christa Peters-Lidard, and Britt Westergard.

In the Mesoscale Symposium: Posters Kristen Rasmussen et al. will present, “Best Practices for Preventing Harassment in Atmospheric Science: Leveraging the RELAMPAGO and WE-CAN Field-Campaign Networks for Collaborative Change.” They report:

This project implemented and studied sexual harassment training, awareness, and experiences during the WE-CAN and RELAMPAGO field campaigns ….Both women and men who attended the training were more likely than those who did not attend to report feeling more trusting of coworkers, comfortable with reporting, and more willing to intervene in situations of harassment. We will present findings about attitudes and experiences of harassment in field work, and we will conclude with a discussion around how the atmospheric science community can facilitate collaborative change around sexual harassment within existing networks.

In the Conference on Education, K. Ryder Fox (University of Miami, Florida) et al. present on “Mental Health Interventions for Marginalized STEM Individuals.”

Also in this conference, Leticia Williams (Howard University) will present “How to Have Difficult Conversations with Underrepresented Students: Best Communication Practices for Multicultural Mentoring to Increase Minority Participation in the Atmospheric Sciences.” In part, they write:

This study examined STEM faculty mentors multicultural mentoring practices and strategies to discuss protégés’ issues and challenges, and the ways that gender and race influenced their communication. Findings revealed that STEM faculty mentors communicated about discrimination and diversity, did not communicate about discrimination and diversity, or did not feel qualified to communicate about discrimination and diversity.

A Legacy of Racism in Science

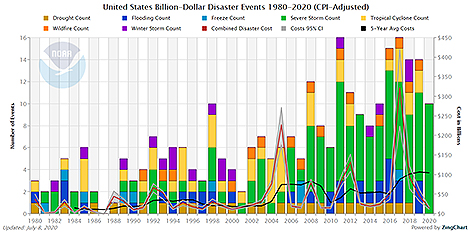

The Symposium on History at the Annual Meeting also picks up on topics of past injustices in the science community—from the treatment of women scientists and the treatment of scientists from other underrepresented groups, to such issues as the under counting of disaster victims from socioeconomically disadvantaged groups, thus potentially skewing scientific and services priorities for many years. One presentation, for example, discusses how “land theft, eugenics, and scientific racism are interwoven into the history of geosciences.”

Social Justice in the Broader Society

Many presentations in the Annual Meeting show that scientists are realizing they have a role in society that is so that social justice issues for the scientific community, go far beyond the diversity and equity inclusiveness within the scientific workforce and its pipeline of future members. Your track of social justice in the Annual Meeting should include such insights.

For example, In one of the Core Science Keynotes, Vernon Morris (Arizona State Univ) tells “A Tale of Two Cities: Comparing Lessons Learned from Community Engagement in Geohealth/Environmental Justice Studies in Washington, D.C., and Gondar, Ethiopia.” Morris “will highlight what has been learned from ‘community-inspired’ environmental health projects at the nexus of air quality – health research, … centered in Washington, DC, and involv[ing] collaboration with activists and residents in low SES and politically disenfranchised communities whose air quality challenges have been exacerbated by gentrification.” Further:

One of the DC studies was able to demonstrate that neighborhood residents were already at risk for airborne particulate matter (PM) exceedances even without the presence of additional point sources. The results were provided in expert testimony at two District of Columbia hearings and a two-year stay from 2012 to 2014 was a direct result of the efforts. Unfortunately, the stay was later overturned and the battle to protect these citizen’s health continues. The other is a study in an open-air hospital in Northern Ethiopia (Gondar). This collaboration involves medical doctors, pharmacists, virologists, and microbiologists at the University of Gondar The Gondar study project combined environmental monitoring, atmospheric sampling, and atmospheric data analysis with the genomic mapping of sampled airborne microflora. Ambient aerobiological samples were collected in order to identify the changes in taxonomically diverse and novel bacteria present on airborne particulate. One specific application of this work was the development of a better understanding of the distribution and transmission of opportunistic microflora within the open-air hospital environment at the University of Gondar Health Sciences Campus. In each case, the original design and scope of the study was significantly modified based on community engagement. The additional diversity in perspective inspired novel inquiry, drove creativity in the implementation of the study, and resulted in greater use-inspired research.

In the Conference on Environment and Health, David Sittenfeld (Museum of Science) et al. are presenting “Wicked Hot Boston: Community Science for Building Extreme Heat Resilience and Addressing Public Health Disparities.” They write:

Urban communities face growing concerns from heat waves that endanger public health, threaten infrastructures, and exacerbate existing social inequities. These impacts fall disproportionately upon people of color, low-income communities, and the elderly. Using a machine learning algorithm. MOS researchers have been working with environmental and community members to produce high-resolution, hyperlocal heat maps that are being actively used by city and regional planners. This session will present results from the mapping activities, with a particular focus on emergent analysis about the heat impacts of urban form in the greater Boston metro area, historic redlining practices, and spatial correlations with … socioeconomic covariates and negative public health outcomes.

We mentioned this next one in our previous blog post delineating a COVID pathway through the Annual Meeting, as it intersects with social justice themes as well, much in the way everything in the production of knowledge, including science, can, either directly or indirectly. The presentation is by Gaige Hunter Kerr et al. in the Conference on Atmospheric Chemistry, “Impact of Coronavirus Lockdowns on NO2: Successes and Challenges for Environmental Inequality in the United States.” They explain in their abstract:

This study highlights the potential for shrinking the gap in pollution exposure between population subgroups in the U.S. but simultaneously underscores the perennial challenges in reducing environmental inequalities.

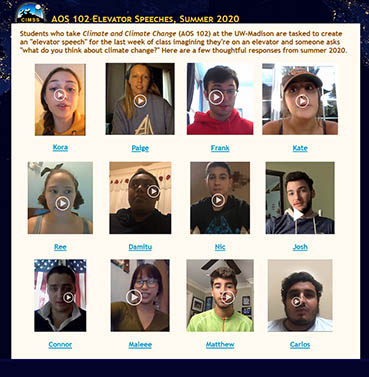

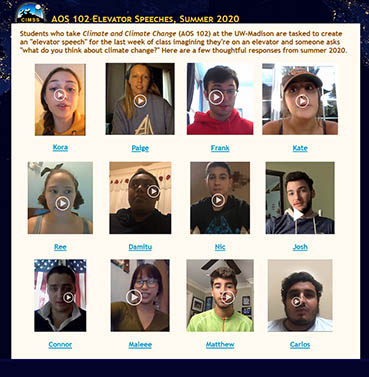

In the Symposium on Societal Applications: Policy, Research, and Practice, Margaret Mooney and Steve Ackerman (both of CIMMS) give voice to student perspectives in a presentation “University Undergraduates Speak Out on Climate Change and Climate Justice.” From their abstract:

NOAA’s Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies (CIMSS) at the University of Wisconsin – Madison collaborates with the Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences (AOS) to offer an online 3-credit course on “Climate and Climate Change” each summer. The class is structured to actively engage students in learning about and communicating about climate change, the later through a weekly discussion forum. Week 1 students upload a video describing their background and motivation for taking the course. Other weeks students respond and interact to varying topics that regularly feature current events. As a capstone activity, students upload an “elevator speech” imagining someone asks “what do you think about climate change?” 2020 prompted uniquely thoughtful discussion posts and passionate elevator pitches referencing racial disparities, climate justice, economics, and a global pandemic. This AMS presentation will share select anonymous responses to the week 5 discussion topic: “identify a scenario in the state or region you grew up where climate and environmental injustices combine to affect people of color more negatively than white people, then research the COVID19 cases for that location” and twelve particularly powerful elevator pitches sanctioned for distribution.  In addition, responses to questions seeking to gauge frequency and comfort around discussing climate change and environmental issues obtained via a follow-up survey will will also be shared in this session.

In addition, responses to questions seeking to gauge frequency and comfort around discussing climate change and environmental issues obtained via a follow-up survey will will also be shared in this session.

In the Conference on Environment and Health, Adora Shortridge, Jennifer Vanos, and William Walker (Arizona State University) present a program to protect children in South Phoenix from extreme heat by preparing neighborhood schools. They write:

In Phoenix, heat is a priority for preparedness and policy plans at the city-level, yet these policies do not always encompass the most vulnerable regions and populations: elementary schoolchildren and low-income neighborhoods. South Phoenix has experienced historical environmental racism and injustice. Residents currently face challenges including higher air temperatures, air pollution, and economic disparities, which can impact children’s health, physical activity, and cognitive abilities. Although children are routinely stated to need additional heat-coping resources, no formal policy or evaluation toolbox exists nationwide to support systematic and effective efforts to protect children from negative consequences of heat at schools. The overarching goal of this research is to create an evaluation tool for “HeatReady Schools.”

In the same conference, Alexis Merdjanoff and Gabriella Meltzer (NYU) present “Falling from Grace”: A Qualitative Study of Disaster Exposure and Downward Mobility among Middle Class Families,” a study of emotional and financial impacts of on families due to Hurricane Sandy:

Prior to Hurricane Sandy, many families had steady paychecks, owned their homes, and had enough discretionary income that they were not constantly constrained by monthly expenses (i.e., middle class). Following Sandy, however, parents expressed that they were unable to participate in activities that they once enjoyed. Instead, once-discretionary income was spent entirely on home repairs, paying bills, or other essential expenses. While parents were clearly conscious of these financial difficulties and attempted to lessen any additional disruptions to their children … this qualitative data reveals the tenuous nature of being middle class in an era of more frequent and severe extreme weather events.

Social Justice Issues with AI in Geosciences

In the Conference on Artificial Intelligence for Environmental Science, Nicol Turner Lee (Brookings Institute) delivers a core science keynote on “The Importance of Fairness in Algorithmic Decision-Making.” Dr. Lee is a senior fellow in Governance Studies, the director of the Center for Technology Innovation, and serves as Co-Editor-In-Chief of TechTank. Her current research portfolio also includes artificial intelligence (AI), particularly machine learning algorithms and their unintended consequences on marginalized communities.

In another invited keynote in the same conference, Ann Bostrom (University of Washington) explores “Three Risk Decision Traps for the Ethical AI Geoscientist.” Shew notes:

Three crises have gripped the sciences in recent years, each stemming from abuses of power. The first, irreproducibility, resulted arguably from incentives to publish and the use and abuse of statistical power in underpowered and overpowered studies. Inattention to power has resulted in, for example, spurious and unreliable findings capturing the limelight and inspiring fatal choices in some instances (e.g., COVID19 self-medication choices), and in other instances may have diverted attention from larger effects and the possibility of disastrous extremes (e.g., sea-level rise). The second, exclusivity—that is, lack of inclusivity and representativeness—results from the internal and societal power dynamics of the scientific enterprise, wherein those with power have tended to reproduce themselves and their epistemologies, to the exclusion of others. Our understanding of how power disparities in science have increased disparities between people continues to evolve, but the use of purportedly scientific arguments to perpetuate racism, and the unintended consequences of science-informed risk policies (e.g., early air bags) for women, children, and vulnerable populations come to mind. The third, inexplicability, has been enabled by exponential growth in computational technology and power, and is evident in the ever-growing complexity and scale of modeling across the sciences (e.g., genetics, climate and weather modeling, pathogeography), increasingly powered by AI. Each of these crises represents a class of power decisions and presents a risk decision trap for AI geoscientists who hope to be ethical. Addressing how these risk decision traps manifest in research designs and science behaviors requires understanding the default decisions and their roots in human judgment and decision making and social context.

The now pervasive use of AI in the sciences and in information and communication technologies (ICT) has captured the spotlight in recent years, bringing to light, for example, the insidious and devastating effects of algorithmic reinforcement of data biases, and the apparently socially destructive consequences of applying, for private profit, social and behavioral science on attention, persuasion, addiction and risky choice to massive microscale observational data. All three crises contribute to these, illustrating how the risk decisions that AI geoscientists now face have trapped other AI scientists. Ethical research design and behavior require AI geoscientists to attend to these risk decision traps. Echo chambers and an absence of common sources of information dominate information use even at the highest levels of government—including for scientific information—increasing the spread of misinformation and disinformation and the exploitation of scientific uncertainties for private ends. Thus, at the same time as science in general has continued to enjoy a relatively high level of confidence and trust from diverse publics, increasing use of social media for news has contributed to the social amplification of scientific risk and uncertainty, with concomitant damage to public good. The three crises highlighted—irreproducibility, exclusivity, and inexplicability—have gained notoriety primarily in other sciences and contexts. But in the AI geosciences too, missteps in risk decisions are likely to have unanticipated consequences. AI geosciences have immediate applications to and consequences for global health and the environment, and for trust in science. Understanding risk decision traps is imperative for the ethical AI geoscientist.

The Themes Keep Coming

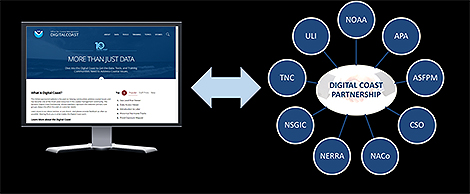

So far we have introduced four themes that cut across conferences and symposia of all types in the 2021 AMS Annual Meeting, and viewing any  number of the video presentations and posters highlighted is easy despite our enormous conference … because for the first time it’s virtual. View at your convenience. Part 1 in our blog series has taken a closer look at major weather events and impacts in 2020 outside of that main program; Part 2 extended our crosscutting approach to weather extremes and climate change; Part 3 was everything COVID-19; and of course Part 4, here, the critical discussions of social justice. The link to the right or here takes you to the Part 5: Community Engagement, now posted.

number of the video presentations and posters highlighted is easy despite our enormous conference … because for the first time it’s virtual. View at your convenience. Part 1 in our blog series has taken a closer look at major weather events and impacts in 2020 outside of that main program; Part 2 extended our crosscutting approach to weather extremes and climate change; Part 3 was everything COVID-19; and of course Part 4, here, the critical discussions of social justice. The link to the right or here takes you to the Part 5: Community Engagement, now posted.