Even though Earth’s atmosphere is laced by more than a billion brilliant discharges of electricity every year, lightning itself never seems ordinary. But there’s a broad range of lightning, and sometimes, at the extreme, it’s possible to recognize a difference between the ordinary and amazing, even among lightning flashes. The challenge is finding and observing such extremes.

New research by Walt Lyons and colleagues, published in BAMS, reports such a perspective-altering observation of long lightning flashes. To appreciate the observation, consider first the “ordinary” lightning flash. The charge center of the cloud itself is typically 6–10 km above ground. And from there the lightning doesn’t necessarily go straight down: it may extend horizontally, even 100 km or more. Typical lightning might be best measured in kilometers or a few tens of kilometers.

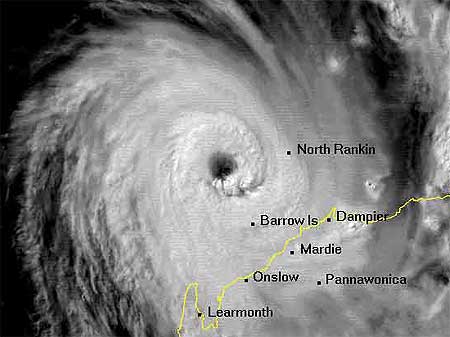

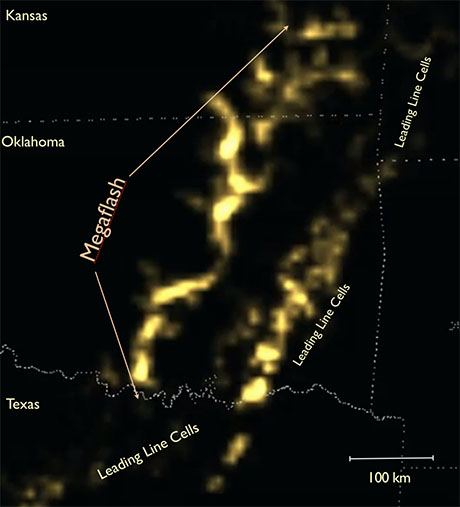

A world record flash in 2007 meandered across Oklahoma for “approximately 300 km.” But that may be a mere cross-counties commute compared to newly discovered interstate “megaflashes” that are almost twice as long. One such megaflash, as the BAMS paper names them, sparked across the sky for ~550 km from northeast Texas across Oklahoma to southeast Kansas in October 2017. And this megaflash, too, may not be the longest ̶ it just happened to occur within the Oklahoma lightning mapping array (OK LMA), allowing for its full study.

Also, just like the official record flash, which produced 13 cloud-to-ground (CG) lightning strikes, including two triggering sprites that shot high into the atmosphere, this horizontal megaflash also triggered a plethora of CG bolts, in-cloud discharges, and upward illuminations during its 7.18 second lifespan.

The new Geostationary Lightning Mapper sensor on the GOES-16/17 satellite has become the latest tool suited to investigating long-path lightning. The BAMS paper says the sensor is showing that a megaflash “appears able to propagate almost indefinitely as long as adequate contiguous charge reservoirs exist” in the clouds. Such conditions seem to be present in mesoscale convective systems—large conglomerates of thunderstorms that extend rainy stratiform clouds across many hundreds of km. The paper adds,

Megaflashes also pose a safety hazard, as they can be thought of as the stratiform region’s version of the ‘bolt-from-the blue,’ sometimes occurring long after the local lightning threat appears to have ended. But some key questions remain – what is the population of megaflashes and how long can they actually become?

The authors conclude:

Is it possible that a future megaflash can attain a length of 1000 km? We would not bet against that. Let the search begin.