Hurricanes like rapidly-changing Harvey are still full of surprises for forecasters.

The remnants of Caribbean Tropical Storm Harvey made a startling burst Thursday from a tropical depression with 35 mph winds to an 85 mph hurricane in a little more than 12 hours. It has been moving steadily toward a collision with the middle Texas coast and landfall is later Friday. If intensification continues at the same rate, Harvey is likely to be a major hurricane by then, according to a Thursday afternoon advisory from the National Hurricane Center, with sustained winds of 120-125 mph and even higher gusts.

That’s a big “if.”

The drop in central pressure, which had been precipitous all day—a sign of rapid strengthening—had largely slowed by Thursday afternoon. Harvey’s wind speed jumped 50 mph in fits during the same time, but leveled off by late afternoon at about 85 mph. Harvey was a strong Category 1 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale by dinner time.

The intensifying process then slowed. But it turns out this was temporary.

Many signs pointed to continued rapid intensification: a favorable, low-shear environment; expanding upper-air outflow; and warm sea surface temperatures. Overnight and Friday morning, Harvey continued to traverse an eddy of water with high oceanic heat content that has detached from the warm Gulf of Mexico loop current and drifted westward toward the Texas coast. Its impact is apparent as the pressure resumed its plunge and winds have responded, blowing Friday morning at a steady 110 mph with higher gusts.

Further intensification is possible.

In fact, the SHIPS (Statistical Hurricane Intensity Prediction Scheme) Rapid Intensification indices “are incredibly high,” Hurricane Specialist Robbie Berg wrote in the Thursday morning forecast discussion. Guidance from the model then showed a 70 percent chance of another 50 mph jump in wind speed prior to landfall. The afternoon guidance lowered those odds a bit, but still showed a a 64 percent probability.of a 35 mph increase.

It wouldn’t the first time a hurricane has intensified rapidly so close to the Texas coast. In 1999 Hurricane Bret did it, ramping up to Category 4 intensity with 140 mph winds before crashing into sparsely populated Kennedy County and the extreme northern part of Padre Island.

Hurricane Alicia exploded into a major hurricane just prior to lashing Houston in 1983. And 2007’s Hurricane Humberto crashed ashore losing its warm water energy source and capping its intensity at 90 mph just 19 hours after being designated a tropical depression that morning off the northern Texas Coast, a similar boost in intensity as Hurricane Harvey.

Rapid intensification so close to landfall is a hurricane forecasting nightmare. An abundance of peer-reviewed papers reveal that there’s a lot more we need to learn about tropical cyclone intensity, with more than 20 papers published in AMS journals this year alone. Ongoing research into rapidly intensifying storms like Harvey, is helping solve the scientific puzzle, including recent cases such as Typhoon Megi and Hurricane Patricia. Nonetheless, despite strides in predicting storm motion in past decades, intensification forecasting remains largely an educated guessing game.

forecasting

Improving Tropical Cyclone Forecasts

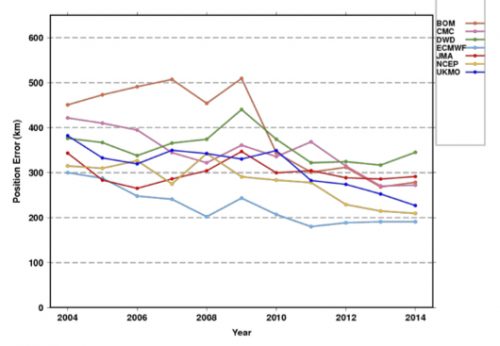

Tropical cyclones are usually associated with bad news, but a long-term study about these storms now posted online for publication in BAMS has some good news–about the forecasts, at least. The authors, a Japanese group lead by Munehiko Yamaguchi, studied operational global numerical model forecasts of tropical cyclones since 1991.

Their finding: the model forecasts of storm positions have improved in the last 25 years. In the Western North Pacific, for example, lead time is two-and-a-half days better. Across the globe, errors in 1 – 5 day forecasts dipped by 6 to 14.5 km, depending on the basin.

Here are the improvements for the globe as a whole. Each line is a different modeling center:

While position forecasts with a single model are getting better (not so much with intensity forecasts), it seems natural that the use of a consensus of the best models could improve results even more. But Yamaguchi et al. say that’s not true in every ocean basin. The result is not enhanced in the Southern Indian Ocean, for example. The authors explain:

This would be due to the fact that the difference of the position errors of the best three NWP centers is large rather than comparable with each other and thus limits the impact of a consensus approach.

The authors point towards ways to improve tropical cyclone track forecasts, because not all storms behave the same:

while the mean error is decreasing, there still exist many cases in which the errors are extremely large. In other words, there is still a potential to further reduce the annual average TC position errors by reducing the number of such large-error cases.

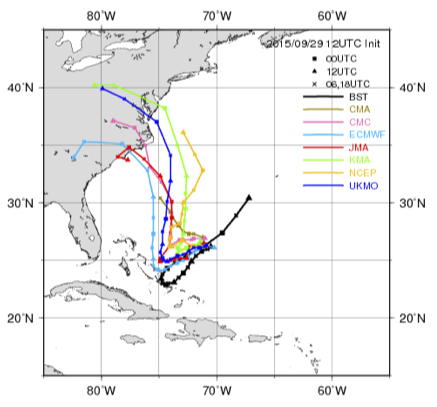

For example, take 5-day track forecasts for Hurricane Joaquin in 2015. Hard to find a useful consensus here (the black line is the eventual track):

Yamaguchi et al. note that these are types of situations that warrant more study, and might yield the next leaps in improvement. They note that the range of forecast possibilities now mapped as a “cone of uncertainty” could be improved by adapting to specific situations:

For straight tracks, 90% of the cyclonic disturbances would lie within the cone, but only 39% of the recurving or looping tracks would be within the cone. Thus a situation-dependent track forecast confidence display would be clearly more appropriate.

Check out the article for more of Yamaguchi et al.’s global perspective on how tropical cyclone forecasts have improved, and could continue to improve.

How does it feel?

Sunday was supposed to be National Weatherperson’s Day. Did you receive flowers? Did distant relatives call to congratulate you? Did adoring fans of your forecasts voice their support?

Or did the much anticipated holiday pass uneventfully while everybody was preoccupied by lesser events…oh, like the Super Bowl, for instance? Just a case of bad scheduling conflicts, or a conscious attempt to diss you?

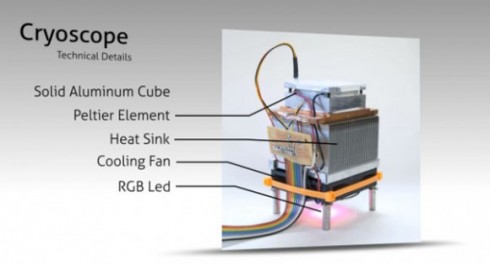

If you’re a meteorologist, especially a forecaster, you know how it feels to be underappreciated, to be told you’re not right often enough, that your job is going to be taken by a computer. Not only might you get ignored on the very day meant for you, now you get replaced…by a cube:

Hook the device to your smart phone weather app and it adjusts its temperature to match the forecast temperature. So that’s how the weather feels! And how does it feel to be replaced by an aluminum box with a heating element and simple sink inside it?

Bob Dylan stuck the knife in with “You Don’t Need a Weatherman to Know Which Way the Wind Blows,” but he twisted it cruelly with:

How does it feel

How does it feel

To be on your own

With no direction home

Like a complete unknown

Like a rolling stone.

A forecaster’s fate? We think not.

Clearly this invention leaves much to be desired. In addition to being unable to prognosticate without a web app, after a decade or more of good minds trying to develop better ways of conveying uncertainty information in weather forecasts in a few words or pictures, here comes a giant deterministic step backward for communicating tomorrow’s conditions. And of course, although inventor Robb Godshaw of Rochester Institute of Technology insists that the Cryoscope compensates for the difference between conducting heat with aluminum versus air (and also effects of wind chill), it is difficult to imagine equating the touch of the hand to how it feels to move and breathe in the atmosphere. No, this box is not how it feels at all.

In fact, there’s a lesson here. Much as it is difficult to teach any scientific concept to a wide audience, let’s keep in mind that over the years people have developed an uncanny sense of how they feel, personally, when it’s 40, or 50, or 60 degrees Fahrenheit and so on (not to mention wiser folks who’ve learned all this in terms of Celsius). In fact, people probably have a much more acute ability to imagine what a 10 degree rise in temperature will feel like than what carrying a 10 pound increase in load will feel like.

The depth to which the temperature scale is ingrained with exquisite sensitivity into our consciousness is summed up by a viewer’s comment on the Cryoscope promo video page:

The step after that would be to hook up a water hose to it to tell you when it is rainy.

Another Way to Work the Night Shift in Meteorology

Meteorologist A.J. Jain dispenses a lot of good advice for young professionals on his blog, Fresh AJ. But in a post last week he aimed his thoughts to employers, giving them a tip on how to keep their forecasting talent from drifting away from the rigors of shift work.

Turns out that Jain finds the demands of job, family, and health wearing him down when he’s working through the night four days and then trying to reset his body clock for the other three.

I know there are many meteorologists out there that currently feel the same way I did. Tired, groggy, and just wish there was another solution. Well I want to introduce you to a new model that is being successfully run at a top aviation weather company on the west coast (I won’t name names…but I am a huge fan!).

The company allows their meteorologists to work from home. Yes…home. Yes you can sit in your pajamas all day or night and work from the goodness of your laptop. How awesome is that!

And you know what is amazing…the turnover of the meteorology department at the aviation company has dropped considerably. The employees are much happier…and the product they put out is just as great…if not better. And they’re still doing shift work!

Read the rest of his points about how telecommuting can be a successful strategy for meteorological shift work.