by Ray Ban, Andrea Bleistein, and Paul Croft, of the AMS Committee to Improve Climate Change Communication (CICCC)

Most AMS Members apparently agree that there is conflict among their colleagues in the Society on the issue of climate change. Those who perceive the conflict on this issue generally see it as at least a partly or somewhat positive thing, but at least some of them—29%, feel reluctance to bring up the topic of global warming at AMS meetings and functions.

Despite the perception of conflict, 82% of voting Members feel AMS should help to educate the public about global warming and 67% think AMS should help educate policy makers about it.

In fact, Members themselves are already involved in this outreach. They are spending significant time educating the public and policy makers about climate change—the median is 10 hours for this past year, and the mean is 55 hours!

Those are some of the key preliminary findings so far from our recent survey of AMS voting Members, e-mailed in December 2011. The survey was a collaboration between our committee, CICCC, and Dr. Ed Maibach at George Mason University. We asked all 7,197 AMS voting Members about their varied perspectives about climate change. Specifically, we hoped to learn about Members’ assessment of the evidence, perception of conflict among our members, views about AMS’s role in public education, and personal involvement in public education activities.

With a response rate of 26%, the survey results may not be easy to extrapolate to the membership as a whole. Nonetheless, we’ve made the preliminary results, which have been vetted by CICCC members and GMU researchers, available for you on the AMS website.

The AMS Commission on the Weather and Climate Enterprise established CICCC in early 2011 to facilitate communication among members of the weather and climate community so as to foster greater understanding about the spectrum of views on climate change. In addition to evaluating responses, the Committee and its partners held two workshops at the 2012 AMS Annual Meeting to facilitate dialogue about climate change within the AMS membership. More such events are planned for the near future.

climate change

The Next Steps for the USGCRP

This week, the National Research Council issued a report of a blue-ribbon panel arguing that the United States Global Change Research Program (USGCRP) may not be able to meet the new decadal goals it’s setting for itself. In less than two weeks, in New Orleans, you’ll get a chance to have your say, too.

USGCRP guides research and disseminates information about climate change, and comprises 13 governmental agencies ranging from the Department of Defense to NASA. The USGCRP assists policymakers; federal, state, and local decision makers; and the public in understanding and adapting to global change.

The program’s new 10-year plan (see draft here; a final version is due next month) broadens USGCRP’s scope from climate to include “climate-related global changes,” building “from core USGCRP capabilities in global climate observation, process understanding, and modeling to strengthen and expand our fundamental scientific understanding of climate change and its interactions with the other critical drivers of global change, such as land-use change, alteration of key biogeochemical cycles, and biodiversity loss.”

The new strategic plan was created to help promote four primary goals of the Program:

- advance scientific knowledge of the integrated natural and human components of the Earth system;

- provide the scientific basis for timely adaptation and mitigation;

- build sustained assessment capacity that improves our understanding, anticipation, and response to global change; and,

- broaden public understanding of global change.

At the AMS Annual Meeting in New Orleans, a Town Hall Meeting (Tuesday, 12:15 p.m., Room 239) will discuss the new strategic plan and examine forthcoming USGCRP initiatives, including integrated modeling and observations, an interagency global change information system, adaptation research, and the National Climate Assessment. The meeting will also discuss how attendees can become involved in USGCRP activities, and will review current and future products, tools, and services that might be useful to both scientists and decision makers.

Implementation of the decadal strategy won’t be without its challenges, however. The recent National Research Council report praises the USGCRP’s ambition in expanding its scope, but it also points out that the Program needs greater expertise in certain areas to sufficiently undertake its new plans.

The USGCRP and its member agencies and programs are lacking in capacity to achieve the proposed broadening of the Program, perhaps most seriously with regard to integrating the social and ecological sciences within research and observational programs, and developing the scientific base and organizational capacity for decision support related to mitigation and adaptation choices. Member agencies and programs have insufficient expertise in these domains and lack clear mandates to develop the needed science.

Additionally, the NRC report notes the lack of overarching governance in the USGCRP, which prevents a cohesive foundation of research areas among the Program’s 13 contributing agencies. As a result, those agencies tend to focus on their own pet projects.

“We were hoping there would be a way to coordinate better, especially on the congressional side,” says NCAR’s Warren Washington, who chaired the NRC committee that prepared the report.

Ultimately, the NRC report notes that “a draft federal plan to coordinate research into how to respond to climate change is unlikely to succeed without added resources and new ways to manage the Program.”

“We do recognize there are some gaps in our capacity,” says the NSF’s Timothy Killeen, the USGCRP vice chair who helped develop the new strategic plan. Program officials welcomed the recommendations outlined in the report and have already made plans to bring in more expertise from academia and other agencies to augment research areas that are lacking, as well as form interagency working groups that could help unify the Program.

IPCC's New Special Report: Adapt to Extremes, but Prepare for the Presentation

For a first reaction to the new Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change special report, Special Report on Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation, read William Hooke’s full post here, but keep in mind his take away message for now:

The world need not just this and the other IPCC reports themselves but also the body of diverse analysis and reaction the reports trigger. IPCC reports should and do stimulate thought and action. They don’t prescribe it.

What should you and I keep in mind as we read?

1. We should remember that the Earth does its business through extreme events and always has. Extremes are not suspensions of the normal order; they are its fulfillment.

2. Extremes leave no sphere of the natural or social or technological world unaffected and the disruptions in all those normally distinct spheres intereact with each other, compounding the challenge.

3. Social change matters more to what extreme events and disasters portend for our future than does climate change. .

4. We’ve got to get past reacting to the crisis of the moment

This will be good preparation not only for reading the full report when it’s available online in February 2012 (the summary is now available here) but also for discussions with Roger Pulwarty and colleagues when the present the reports findings on the first day of the upcoming AMS Annual Meeting in New Orleans (23 January, 11:30 a.m., Room 243). If you’re interested in hearing from the report authors now, check out the video from Friday’s press conference:

Weathercasters in Multiple Exposures

A recent blog post by Bob Henson, author of the new AMS book, Weather on the Air, serves as a good summary of the growing news coverage of broadcast meteorologists’ take on global warming. Much of this coverage stems from a recent survey of weathercasters released by George Mason University, in which, as Henson notes:

…the most incendiary finding was that 26% of the 500-plus weathercasters surveyed agreed with the claim that “global warming is a scam,” a meme supported by Senator James Inhofe and San Diego weathercaster John Coleman. On the other hand, only about 15% of TV news directors agreed with the “scam” claim in another recent survey by Maibach and colleagues. And Maibach himself stresses the glass-half-full finding that most weathercasters are interested in climate change and want to learn more.

Henson cites The New York Times, National Public Radio, ABC’s Nightline, and Comedy Central’s The Colbert Report as some of those that have examined the issue recently. The most recent “exposé” was a 10-minute segment entitled “Weather Wars,” on Australian “Dateline”; it features a number of AMS members.

Is Science Messy Enough for You?

Brooks Garner, broadcast meteorologist with WIS-TV in Columbia, South Carolina, shares on his blog some interesting impressions from the climate variability and change sessions at the recent AMS meeting in Atlanta. He notes that the process of science we witnessed at the AMS meeting doesn’t fit the pace of the contemporary mindset:

In a culture characterized by the hunger for “instant gratification” (“IG”) in everything from consumerism to relationships, naturally science is struggling through the same tide….

He witnesses some contentious arguments, glaring discrecpancies in interpretations, and clashing priorities that fueled some occasionally tense sessions in Atlanta, like a science “reality show.” Even amid this scientific culture of constant debate and disagreement and incremental progress in understanding, Garner can see that experts overwhelmingly agree that warming is happening and we can’t ignore the consequences. He can also see why the public is not always convinced

[I]nstant gratification will never occur on the topic of global warming. Science will never agree completely in its effects or a solution. But one thing I can guarantee you: the research will never stop, the debate will never cool, and the naysayer’s will never rest. If they did, it would no longer be ‘science’, but instead ‘belief’.

Then he adds a piece of good advice:

Do you “believe” in global warming? I hope not. I hope that everyone would stop “believing” and instead spend that energy learning as much as possible about the subject.

This attitude is the antithesis of instant gratifcation; one striking aspect of Garner’s viewpoint is how similar it is to another blogger-scientist who posted not long after the East Anglia e-mails made the news.

Thomas Zurbuchen is Associate Dean at the Center for Entrepreneurship in the College of Engineering of the University of Michigan. In a posting titled, “Messy Science,” Zurbuchen wrote that the scientists’ e-mails didn’t tell him anything new about climate change, but the huge number of comments about the e-mails he’d received were disturbing.

I am left with a deep sense that most people don’t understand science, or its pursuit. Doing science is more like orienteering, and less like a 100 meter dash. Doing science is messy!

“Most people” includes science grad students, Zurbuchen says. A lot of grad students expect quick success–or at least steady success with every project. They don’t realize that a lot of ideas and hard work are flushed away by competing evidence.

To most budding scientists, this leads to a major crisis. Now, they have to decide whether they want to be a scientist! As they go forward, they notice that science is about search, and struggles. It is about false starts, about failed projects. It’s not about victory [laps]….

The East Anglia e-mails, he said, showed how frustrated scientists can become, which leads to all sorts of behavior, including lashing out at the peer review system. While an instant gratification culture may not be able to embrace scientists’ oft-fallible responses to a rock-solid, rock-slow process, Zurbuchen, like Garner, sees signs of the health of the enterprise despite the humanity of the participants:

Yes, science is not an orderly, straightforward path. It is littered with messy turns and twists. For me, that has been the only reason I have become a scientist. If it was predictable, everybody could be a successful scientist!

AMS on NPR

NPR reporter Jon Hamilton was in Atlanta for the AMS Annual Meeting, searching for the effects of the hacked climate scientists’ emails. He interviewed a number of people at the meeting, with the resulting segment (transcript and audio here) that aired on Morning Edition on Thursday.

The quoted scientists were: Kevin Goebbert, Valparaiso University; Dave Gutzler, University of New Mexico; Chris Folland, UK Met Office; Marcus Williams, Florida State University; and Bill Hooke, AMS Policy Program.

A Minimum of Maximum Concern

There are a lot of questions about the current solar minimum, which has reached historic levels—“No solar physicist alive today has experienced a minimum this deep or this long,’’ according to NASA’s Madhulika Guhathakurta, lead program scientist for NASA’s Living With A Star program, which studies solar variability and its effects on Earth. Some of the effects of the minimum are fairly clear to scientists: the amount of cosmic rays entering our portion of the solar system is greater than normal, and Earth’s ionosphere has shrunk.

The debate is instead partly about the effect of the minimum on Earth’s climate. A recent study by Judith Lean of the Naval Research Lab and David Rind of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies suggests that decreased solar irradiance during the current minimum cycle may be slightly offsetting recent warming attributed to greenhouse gases. Even if the minimum is affecting climate, it may be of minimal consequence.

“. . . [O]nly about 10 percent of climate variation is due to the sun,” notes Leon Golub, senior astrophysicist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Institute for Astrophysics. “That means 90 percent isn’t.”

Just as importantly, the solar minimum won’t last forever, so any climatic effects are temporary, as well. But when will solar activity turn around? The current minimum began in 2000 and has been particularly deep for the last two years. At the AMS Annual Meeting, Joseph Kunches of NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center attempts to pinpoint the arrival of the next solar maximum and ponders its potential effects in his presentation, “Solar Cycle Update—Will the New Cycle Please Start?” (Monday, 2:15–2:30 p.m., B303). And Matthew J. Niznik and W. F. Denig of the National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service introduce a new indicator, the Genesis Minimum Quiet Day Index, which analyzes sunspot activity and suggests that the current solar minimum is not anomalous. Their index and the larger topic of the influence of solar activity on Earth’s climate are explored in their poster, “Impacts of Extended Periods of Low Solar Activity on Climate” (Monday, 2:30–4:00 p.m., exhibit hall B2).

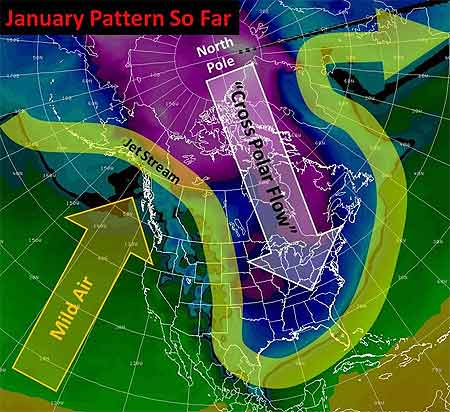

Harsh Cold Wave Slowly Retreating

Well, the big winter cold snap that has been gripping much of the United States since December is nearing its end. Temperatures in most places from the Plains to the East Coast have started to rebound and no renewed surges of Arctic air are on the horizon after a final weak front moves through the East Tuesday. But the damage is done in places from the Dakotas and Montana to Florida: burst pipes, roads that drifted shut, and wind chills lower than -50 in the North, and car crashes on icy roads, power outages, and record cold that has chilled the South.

Last Thursday, the wind chill in Bowbells, North Dakota hit 52° F below zero. That degree of cold “freezes your nostrils, your eyes water, and your chest burns from breathing — and that’s just going from the house to your vehicle,” said Jane Tetrault of Burke County. Her vehicle started, but the tires were frozen. “It was bump, bump, bump all the way to work with the flat spots on my tires,” she said, adding, “It was a pretty rough ride.”

Snow and icy winds whipped southward from the Midwest into Tennessee, Georgia, and Alabama late in the week, making travel a disaster in Memphis and Atlanta. Video of cars sliding off roads or into each other played every half hour on The Weather Channel into the weekend.

Even the Sunshine State had wintry precipitation with this unusual cold surge—something not seen in more than 30 years. The weekend into Monday was especially brutal by Florida standards. With temperatures in the 30s and low 40s, light rain enveloped the peninsula Friday night through Saturday. Sleet fell in spots from Jacksonville and Ocala southward through Orlando, Tampa, and Melbourne into Palm Beach. A few wet snowflakes mixed in here and there with snow reported by trained spotters as far south as Kendall, a southern suburb of Miami. In some places north of Tampa, enough sleet accumulated on cars and outdoor furniture to build little “sleet” men, complete with tiny hats and tree-twig arms, their photos rivaling those taken of snowmen built in Tampa on January 17, 1977. (View a of Florida sleet from a snow and ice slideshow on Tampa’s baynews9.com.)

Clearing led to record morning lows both Sunday and Monday that threatened harm to Florida’s $3 billion citrus industry. Temperatures bottomed out at 25° in Tampa, 29° in Orlando, and 31° in Ft. Myers. On Sunday, the temperature in Miami tied the 1970 record for the date with 35°, and a 36° low Monday morning broke the previous record for the date of 37° set in 1927. Despite the records, it has been the duration of the cold, especially in the South, that makes this cold snap memorable. Morning after morning since the previous weekend, photos of Florida strawberries encased in ice showed up on newscasts. Such protective measures against the frigid temperatures are expected for several more mornings in central Florida, even as the chill slowly moderates.

The cold was even long-lasting in the Midwest and Plains, as noted in TWC meteorologist Tim Ballisty’s article “It’s Cold But So What?” last week. He points out that Chicago hasn’t been above freezing since Christmas Day, at the time 11 straight days and counting. Cleveland had 10 consecutive days of snow, and that count continued right into the weekend.

Unlike the extensive heat waves of recent summers, this long and harsh cold snap resulted in relatively few new temperature records. At the Annual Meeting in Atlanta, Gerry Meehl of NCAR will explore the rising ratio of record high temperatures to record low temperatures, which is expected to markedly increase by the middle of the century with current projections of climate warming.

Innovations in Climate Adaptation

UPDATE, 1/17/10: Due to a last-minute scheduling change, Amanda Lynch will be unable to attend the Annual Meeting. Adaptive Governance and Climate Change will still be a featured release at the AMS Book Launch Party on Monday.

The recent Copenhagen conference provided yet more evidence that countries with completely different priorities are often reluctant to enter into complex and costly agreements with each other. While international negotiations may seem cumbersome at best, some scholars argue that climate change may best be solved at the local–rather than international–level. Local action may not only be more effective but also could also someday might lead to international agreements.

This local-first policy approach will be explored in a variety of ways at the AMS Annual Meeting, headlined by the release of a new AMS book, Adaptive Governance and Climate Change, by Ronald Brunner and Amanda Lynch. Brunner and Lynch show how locally based programs foster the necessary diversity and innovation for climate adaptation.  Their book focuses on the real-life climate issues faced by Barrow, Alaska—and analyzes how the policies developed to address those issues could be adopted by other communities.

Their book focuses on the real-life climate issues faced by Barrow, Alaska—and analyzes how the policies developed to address those issues could be adopted by other communities.

In Atlanta, Lynch will be available to discuss these policy perspectives when the book is released as part of the AMS Book Launch Party (Monday, 5:30 p.m., exhibit hall B1, booth 146). In addition, she will be signing copies of the book on Monday and Wednesday (2:45–4:00 p.m., exhibit hall B2).

Communities across the world are moving toward adaptive governance, as can be seen in a number of presentations at the Annual Meeting. Nanteza Jamiat’s poster on “Adaptation Challenges to Climate Change Disasters in the Karamoja Cluster (Cattle Corridor) in Uganda” (at the student poster session, Sunday, 5:30–7:00 p.m., exhibit hall B2) addresses the interrelationship of climate change and agriculture in a country where both are a way of life for most of the population. Barry Smit’s presentation on “Traditional Knowledge and Adaptation to Climate Change in the Canadian Arctic” (Wednesday, 9:00–9:15 a.m, B213) focuses on indigenous people in the Arctic and the cultural barriers that sometimes need to be broken in order to implement local adaptation initiatives. The Pacific Island nation of Tuvalu is the subject of “Weathering the Waves: Climate Change, Politics, and Vulnerability in Tuvalu,” a poster by Heather Lazrus (Monday, 2:30–4:00 p.m., exhibit hall B2) that shows how one of the most vulnerable areas in the world is in some cases reverting to traditional governmental methods to meet the perils of climate change. And Cynthia Fowler’s presentation on “Coping in Kodi: Local Knowledge about and Responses to Climate Change and Variable Weather on Sumba (Eastern Indonesia)” (Tuesday, 4:15-4:30 p.m., B213) notes that many people in Indonesia’s marginal environments relate climate change to local development, thus crystallizing in one small area many of the problems that were evident at Copenhagen between developing and developed countries.

Charting the Course of Arctic Warmth…and Oceanography

While many parts of the country have recently been experiencing conditions that residents might call “Arctic,” the Arctic region itself has been warming since at least the early 1990s, reaching warmth unprecedented in the last century. The consequences for global climate are potentially critical―particularly if fresh water from melting ice and increased atmospheric precipitation in the Arctic slow the overturning circulation of the North Atlantic. With Arctic sea ice melting dramatically in recent years, scientists are trying to understand the influence of the warmer water that flows into the Arctic from the North Atlantic.

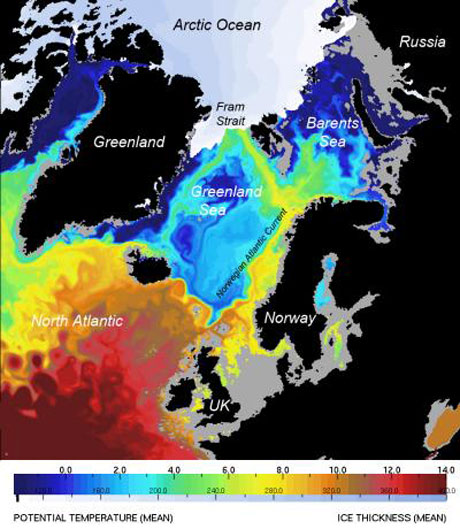

At the National Oceanography Centre (NOCS) in Southampton, United Kingdom, scientists using high-resolution computer models found that from 1989 to 2009, about 50% of the salty North Atlantic water entering the Arctic Ocean came through Fram Strait, a deep channel between Greenland and the Norwegian island of Spitsbergen that connects the Nordic Seas to the Arctic Ocean. The Barents Sea contributes about as much Atlantic water to the Arctic, but the Fram Strait water carried most of the heat that has been a primary cause of Arctic ice melting.

An example of the modeling in this study, published in the January 2010 issue of Journal of Marine Systems, can be seen in the image below, which shows a computer simulation of ocean temperatures at a depth of 100 meters and sea ice thickness in September 2006. The pathways of warm saline water toward the Arctic have previously been poorly understood, but here the 8-km resolution defines three distinct pathways for this water to move under the more pure Arctic water, thus pumping heat northward between 50 and 170 meters below the surface.

“Computers are now powerful enough to run multidecadal global simulations at high resolution,” said NOCS scientist Yevgeny Aksenov. “This helps to understand how the ocean is changing and to plan observational programs so as to make measurements at sea more efficient.”

Ocean-climate interactions are a primary focus of the ocean science research priorities recommended by the U.S. National Science and Technology Council’s Joint Subcommittee on Ocean Science and Technology (JSOST) in their 2007 report, “Charting the Course for Ocean Science in the United States for the Next Decade: An Ocean Research Priorities Plan and Implementation Strategy.” As our understanding continues to evolve regarding the ocean and its influence on the Earth system, the priorities outlined in this report have also evolved. A town hall meeting on “Refreshing Our Ocean Research Priorities” (Monday, 12:15–1:15 p.m., B212) at the upcoming AMS Annual Meeting will explore some of these developments and give participants a forum to discuss topics of interest with the chairs of JSOST.