An unusual atmospheric phenomenon over Norway (above, photographed by Jan Petter Jørgensen) and elsewhere in northern Europe recently led some people to believe they were witnessing alien activity. Only later did the Russian Defense Ministry reveal that a test of an intercontinental missile launched from a submarine in the White Sea had failed at the same time as the mysterious display in the sky appeared.

While the Russians didn’t directly connect the two, many military experts noted that a malfunctioning missile could give such a spiraling appearance. So while the Land of the Midnight Sun apparently isn’t also the Land of the Midnight UFO, it does bring up the question for you, our readers: How does a missile cause this spiralling effect? Here’s one possible explanation:

The Ballots Are In…Now Meet the Winners

With the New Year comes the season for annual awards and “Best of” lists of every kind, from Oscars to best beer to best iPhone apps. But how often do you actually get invited to the awards ceremony? Here in Atlanta you can practically walk the red carpet with the winners.

On Wednesday at 4:45 p.m. (Publisher’s Row, Exhibit Hall), Atmospheric Science Librarians International (ASLI) will be presenting its fifth annual ASLI Choice awards for the Best Books of 2009.

This year’s winner in the “science” category is Clouds in the Perturbed Climate System: Their Relationship to Energy Balance, Atmospheric Dynamics, and Precipitation, edited by Jost Heintzenberg and Robert J. Charlson. According to ASLI, it was selected for its “quality, authoritativeness, and comprehensive coverage of new and important aspects of cloud research.”

A new category for “popular” books was added to this year’s awards, and the winner is this class is Planet Ice: A Climate for Change, with photography by James Martin and essays by Yvon Chouinard. It was chosen for “beautiful photography accompanied by thoughtful essays on a topical and timely subject.”

Runners-up in the “science” category are Aerosol Pollution Impact on Precipitation : A Scientific Review, edited by Zev Levin and William R. Cotton, for an “authoritative, well organized, forum-based approach to the evaluation of a problem of global significance”; Hydroclimatology: Perspectives and Applications, by Marlyn L. Shelton, for a “well-considered, well-referenced text on an important topic”; and Climate Change and Biodiversity: Implications for Monitoring Science and Adaptive Planning, by D. C. MacIver, M. B. Karsh and N. Comer, for “good, clear authoritative statistical compilations, graphics, and charts on a important subject.”

And if we may blow our own horn for a moment, the runner-up in the “popular” category is Jack Williams’s AMS Weather Book: The Ultimate Guide to America’s Weather, with ASLI noting “its accessible and informative approach to all aspects of weather, and the richness of its illustrations.”

Publisher’s Row will also be the place to find the AMS books booth as well as some of the other leading publishers of atmospheric science books. In fact, along with the AMS Weather Book, two of the other ASLI’s Choice winners are published by companies that will be displaying their titles at the meeting: Aerosol Pollution Impact on Precipitation (published by Springer) and Hydroclimatology (published by Cambridge University Press).

Congratulations to all the winners!

Dress for the Ocean's Success

A group of organizations supporting the creation of a national policy to protect oceans, coasts, and lakes has declared Wednesday, January 13, “Wear Blue for Oceans” Day. Rallies will be held in 10 cities across the nation, including San Francisco, New Orleans, Honolulu, and Washington D.C. To show your support, organizers are asking you to wear blue, even if you’re not attending, so here are two of our suggestions for tomorrow’s attire.

A Minimum of Maximum Concern

There are a lot of questions about the current solar minimum, which has reached historic levels—“No solar physicist alive today has experienced a minimum this deep or this long,’’ according to NASA’s Madhulika Guhathakurta, lead program scientist for NASA’s Living With A Star program, which studies solar variability and its effects on Earth. Some of the effects of the minimum are fairly clear to scientists: the amount of cosmic rays entering our portion of the solar system is greater than normal, and Earth’s ionosphere has shrunk.

The debate is instead partly about the effect of the minimum on Earth’s climate. A recent study by Judith Lean of the Naval Research Lab and David Rind of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies suggests that decreased solar irradiance during the current minimum cycle may be slightly offsetting recent warming attributed to greenhouse gases. Even if the minimum is affecting climate, it may be of minimal consequence.

“. . . [O]nly about 10 percent of climate variation is due to the sun,” notes Leon Golub, senior astrophysicist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Institute for Astrophysics. “That means 90 percent isn’t.”

Just as importantly, the solar minimum won’t last forever, so any climatic effects are temporary, as well. But when will solar activity turn around? The current minimum began in 2000 and has been particularly deep for the last two years. At the AMS Annual Meeting, Joseph Kunches of NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center attempts to pinpoint the arrival of the next solar maximum and ponders its potential effects in his presentation, “Solar Cycle Update—Will the New Cycle Please Start?” (Monday, 2:15–2:30 p.m., B303). And Matthew J. Niznik and W. F. Denig of the National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service introduce a new indicator, the Genesis Minimum Quiet Day Index, which analyzes sunspot activity and suggests that the current solar minimum is not anomalous. Their index and the larger topic of the influence of solar activity on Earth’s climate are explored in their poster, “Impacts of Extended Periods of Low Solar Activity on Climate” (Monday, 2:30–4:00 p.m., exhibit hall B2).

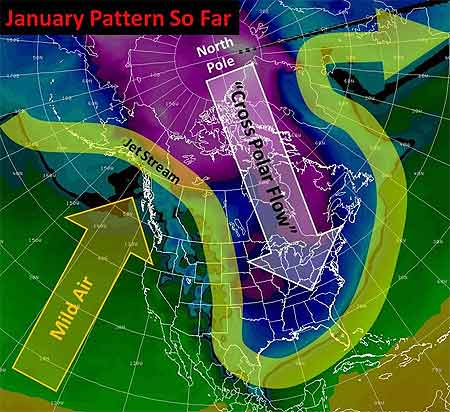

Harsh Cold Wave Slowly Retreating

Well, the big winter cold snap that has been gripping much of the United States since December is nearing its end. Temperatures in most places from the Plains to the East Coast have started to rebound and no renewed surges of Arctic air are on the horizon after a final weak front moves through the East Tuesday. But the damage is done in places from the Dakotas and Montana to Florida: burst pipes, roads that drifted shut, and wind chills lower than -50 in the North, and car crashes on icy roads, power outages, and record cold that has chilled the South.

Last Thursday, the wind chill in Bowbells, North Dakota hit 52° F below zero. That degree of cold “freezes your nostrils, your eyes water, and your chest burns from breathing — and that’s just going from the house to your vehicle,” said Jane Tetrault of Burke County. Her vehicle started, but the tires were frozen. “It was bump, bump, bump all the way to work with the flat spots on my tires,” she said, adding, “It was a pretty rough ride.”

Snow and icy winds whipped southward from the Midwest into Tennessee, Georgia, and Alabama late in the week, making travel a disaster in Memphis and Atlanta. Video of cars sliding off roads or into each other played every half hour on The Weather Channel into the weekend.

Even the Sunshine State had wintry precipitation with this unusual cold surge—something not seen in more than 30 years. The weekend into Monday was especially brutal by Florida standards. With temperatures in the 30s and low 40s, light rain enveloped the peninsula Friday night through Saturday. Sleet fell in spots from Jacksonville and Ocala southward through Orlando, Tampa, and Melbourne into Palm Beach. A few wet snowflakes mixed in here and there with snow reported by trained spotters as far south as Kendall, a southern suburb of Miami. In some places north of Tampa, enough sleet accumulated on cars and outdoor furniture to build little “sleet” men, complete with tiny hats and tree-twig arms, their photos rivaling those taken of snowmen built in Tampa on January 17, 1977. (View a of Florida sleet from a snow and ice slideshow on Tampa’s baynews9.com.)

Clearing led to record morning lows both Sunday and Monday that threatened harm to Florida’s $3 billion citrus industry. Temperatures bottomed out at 25° in Tampa, 29° in Orlando, and 31° in Ft. Myers. On Sunday, the temperature in Miami tied the 1970 record for the date with 35°, and a 36° low Monday morning broke the previous record for the date of 37° set in 1927. Despite the records, it has been the duration of the cold, especially in the South, that makes this cold snap memorable. Morning after morning since the previous weekend, photos of Florida strawberries encased in ice showed up on newscasts. Such protective measures against the frigid temperatures are expected for several more mornings in central Florida, even as the chill slowly moderates.

The cold was even long-lasting in the Midwest and Plains, as noted in TWC meteorologist Tim Ballisty’s article “It’s Cold But So What?” last week. He points out that Chicago hasn’t been above freezing since Christmas Day, at the time 11 straight days and counting. Cleveland had 10 consecutive days of snow, and that count continued right into the weekend.

Unlike the extensive heat waves of recent summers, this long and harsh cold snap resulted in relatively few new temperature records. At the Annual Meeting in Atlanta, Gerry Meehl of NCAR will explore the rising ratio of record high temperatures to record low temperatures, which is expected to markedly increase by the middle of the century with current projections of climate warming.

Innovations in Climate Adaptation

UPDATE, 1/17/10: Due to a last-minute scheduling change, Amanda Lynch will be unable to attend the Annual Meeting. Adaptive Governance and Climate Change will still be a featured release at the AMS Book Launch Party on Monday.

The recent Copenhagen conference provided yet more evidence that countries with completely different priorities are often reluctant to enter into complex and costly agreements with each other. While international negotiations may seem cumbersome at best, some scholars argue that climate change may best be solved at the local–rather than international–level. Local action may not only be more effective but also could also someday might lead to international agreements.

This local-first policy approach will be explored in a variety of ways at the AMS Annual Meeting, headlined by the release of a new AMS book, Adaptive Governance and Climate Change, by Ronald Brunner and Amanda Lynch. Brunner and Lynch show how locally based programs foster the necessary diversity and innovation for climate adaptation.  Their book focuses on the real-life climate issues faced by Barrow, Alaska—and analyzes how the policies developed to address those issues could be adopted by other communities.

Their book focuses on the real-life climate issues faced by Barrow, Alaska—and analyzes how the policies developed to address those issues could be adopted by other communities.

In Atlanta, Lynch will be available to discuss these policy perspectives when the book is released as part of the AMS Book Launch Party (Monday, 5:30 p.m., exhibit hall B1, booth 146). In addition, she will be signing copies of the book on Monday and Wednesday (2:45–4:00 p.m., exhibit hall B2).

Communities across the world are moving toward adaptive governance, as can be seen in a number of presentations at the Annual Meeting. Nanteza Jamiat’s poster on “Adaptation Challenges to Climate Change Disasters in the Karamoja Cluster (Cattle Corridor) in Uganda” (at the student poster session, Sunday, 5:30–7:00 p.m., exhibit hall B2) addresses the interrelationship of climate change and agriculture in a country where both are a way of life for most of the population. Barry Smit’s presentation on “Traditional Knowledge and Adaptation to Climate Change in the Canadian Arctic” (Wednesday, 9:00–9:15 a.m, B213) focuses on indigenous people in the Arctic and the cultural barriers that sometimes need to be broken in order to implement local adaptation initiatives. The Pacific Island nation of Tuvalu is the subject of “Weathering the Waves: Climate Change, Politics, and Vulnerability in Tuvalu,” a poster by Heather Lazrus (Monday, 2:30–4:00 p.m., exhibit hall B2) that shows how one of the most vulnerable areas in the world is in some cases reverting to traditional governmental methods to meet the perils of climate change. And Cynthia Fowler’s presentation on “Coping in Kodi: Local Knowledge about and Responses to Climate Change and Variable Weather on Sumba (Eastern Indonesia)” (Tuesday, 4:15-4:30 p.m., B213) notes that many people in Indonesia’s marginal environments relate climate change to local development, thus crystallizing in one small area many of the problems that were evident at Copenhagen between developing and developed countries.

NWS Increases Severe Hail Threshold

If you step outside in a thunderstorm and get bonked on the head with penny size hail, don’t blame your misfortune on a severe storm. On January 5, the National Weather Service changed the criteria for severe thunderstorms by upping the minimum size hail from ¾ to 1 inch—quarter size. The wind threshold—50 knots, or 58 mph—remains the same.

The reason for the change, according to a statement issued by the Fire and Public Weather Services Branch of the NWS, is that research reveals “significant damage” doesn’t occur from hail smaller than an inch. Hailstones the size of quarters or larger are the ones most destructive to cars, homes, buildings, and crops.

Over the years, and particularly in the Plains states, the statement reads, “the frequency of severe thunderstorm warnings issued for penny-size and nickel-size hail might have desensitized the public to take protective action during a severe thunderstorm warning.” Too many warnings for events that were not damaging garnered complaints and made the warnings somewhat meaningless.

Experimental warnings for 1-inch hail in Kansas the last few years expanded in the central and western United States in 2009. Emergency managers and media outlets in the areas that previously made the changes noted that people seem to take warnings for severe hail more seriously now as they carry more weight.

Of course observing hailstones 1 inch or larger and forecasting hail size are two different things. But, just as research has supported increasing the severe hail threshold, scientists are making strides toward more accurately predicting hail size from radar observations of severe thunderstorms. A poster that will be presented by Matthew Kramar of the NWS office in the Washington, D.C. area, et al., on Wednesday afternoon at the Annual Meeting (January 20, 2:30-4:00 PM, Exhibit Hall B2) reveals results of correlating radar hail cores to hail size for the Mid-Atlantic region—a study that piggybacks on successes in establishing operational hail prediction in the Plains states.

Shedding New Light on Night-Shining Clouds

Scientists have been making new progress in solving the mysteries of noctilucent clouds [also known as Polar Mesospheric Clouds (PMCs)], thanks to NASA’s Aeronomy of Ice in the Mesosphere (AIM) satellite. AIM recently recorded a series of complete polar seasons of these clouds, which form in the mesosphere and are only visible on Earth when illuminated by sunlight from below the horizon. The satellite’s findings “have altered our previous understanding of why PMCs form and vary,” according AIM principal investigator James Russell III of Hampton University in Virginia.

AIM observed the PMCs in each hemisphere’s summer season at all longitudes and over a latitude range of 60°–85°; this video shows the clouds in the northern skies from late May to mid-August of 2009.

AIM’s data revealed that the clouds form and dissipate at very high speeds and may be affected by high-altitude weather systems.

“The cloud season abruptly turns on and off going from no clouds to near complete coverage in a matter of days, with the reverse pattern occurring at the season end,” Russell said. Russell likens this seasonal on-off switch to a “geophysical light bulb” in the presentation he will make about the new findings at the Space Weather Symposium during the AMS Annual Meeting in Atlanta (Tuesday, 8:30 AM, B303).

Noctilucent clouds are made of ice crystals that form when water vapor condenses onto dust particles at extremely cold temperatures (around -210° to -235°F). Scientists are using the new imagery as well as computer models to figure out more about what conditions trigger the clouds. So far, the new data indicate that high altitude temperature determines the onset, variability, and end of the cloud season. Satellite imagery also seems to show relationships to planetary waves as well as smaller scale gravity waves in the atmosphere.

Charting the Course of Arctic Warmth…and Oceanography

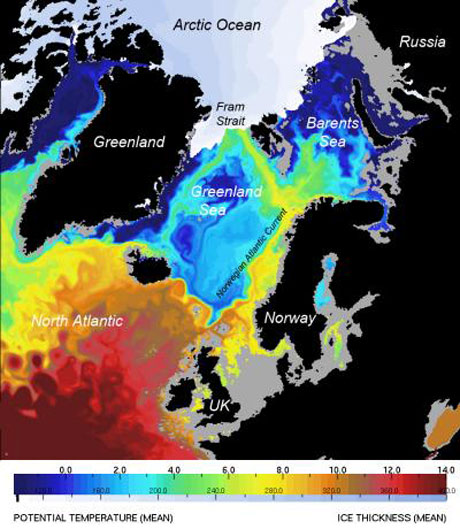

While many parts of the country have recently been experiencing conditions that residents might call “Arctic,” the Arctic region itself has been warming since at least the early 1990s, reaching warmth unprecedented in the last century. The consequences for global climate are potentially critical―particularly if fresh water from melting ice and increased atmospheric precipitation in the Arctic slow the overturning circulation of the North Atlantic. With Arctic sea ice melting dramatically in recent years, scientists are trying to understand the influence of the warmer water that flows into the Arctic from the North Atlantic.

At the National Oceanography Centre (NOCS) in Southampton, United Kingdom, scientists using high-resolution computer models found that from 1989 to 2009, about 50% of the salty North Atlantic water entering the Arctic Ocean came through Fram Strait, a deep channel between Greenland and the Norwegian island of Spitsbergen that connects the Nordic Seas to the Arctic Ocean. The Barents Sea contributes about as much Atlantic water to the Arctic, but the Fram Strait water carried most of the heat that has been a primary cause of Arctic ice melting.

An example of the modeling in this study, published in the January 2010 issue of Journal of Marine Systems, can be seen in the image below, which shows a computer simulation of ocean temperatures at a depth of 100 meters and sea ice thickness in September 2006. The pathways of warm saline water toward the Arctic have previously been poorly understood, but here the 8-km resolution defines three distinct pathways for this water to move under the more pure Arctic water, thus pumping heat northward between 50 and 170 meters below the surface.

“Computers are now powerful enough to run multidecadal global simulations at high resolution,” said NOCS scientist Yevgeny Aksenov. “This helps to understand how the ocean is changing and to plan observational programs so as to make measurements at sea more efficient.”

Ocean-climate interactions are a primary focus of the ocean science research priorities recommended by the U.S. National Science and Technology Council’s Joint Subcommittee on Ocean Science and Technology (JSOST) in their 2007 report, “Charting the Course for Ocean Science in the United States for the Next Decade: An Ocean Research Priorities Plan and Implementation Strategy.” As our understanding continues to evolve regarding the ocean and its influence on the Earth system, the priorities outlined in this report have also evolved. A town hall meeting on “Refreshing Our Ocean Research Priorities” (Monday, 12:15–1:15 p.m., B212) at the upcoming AMS Annual Meeting will explore some of these developments and give participants a forum to discuss topics of interest with the chairs of JSOST.

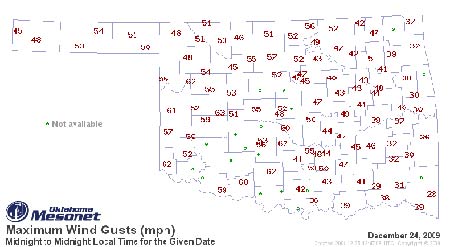

This Christmas, the Gift of Salience

Midwesterners take pride in their ability to handle blizzards and ice that make walking and driving miserable and harrowing, not to mention downright dangerous. Even so, yesterday, people generally stayed off the roads, canceling long awaited Christmas Eve events. Those who ventured out often ran into trouble, according to news reports:

Betsy Graupe lost count of the number of vehicles she saw in the ditch while driving from Chicago to see her family in Minneapolis, a journey of some 350 miles (570 kilometers).

“It was very, very bad out,” said Graupe, who ended up pulling off the highway and spending Wednesday night in a hotel.

“It was poor visibility, and icy and the road was rutted… it was quite an adventure.”

Were the people who spun out beside the road lacking experience with winter? Were they unaware of the situation? Were they making a bad calculation of the risks, or just unlucky?

We’ll probably never know unless some enterprising social scientist follows up. Scientists did follow up on one recent storm—the miserable icing in January 2007 that turned roads into skating rinks in the nation’s midsection during the AMS Annual Meeting in San Antonio.

If you remember, hundreds of attendees never made it to that meeting due to airport and road closures. Kim Klockow and Randy Peppler of the University of Oklahoma polled their peers about travel to that meeting. Their findings, presented at the 2008 AMS Annual Meeting (and published this summer in the NCAR newsletter, Weather and Society Watch), show that very few of their cohorts chose to stay home. Some avoided hopeless airline delays by choosing to drive despite road conditions. Some were anxious about the trip from Norman to San Antonio, some were not. Many left early, others left late, but they found ways to deal with the weather, minimizing but not eliminating travel risks. Access to information gave them enough confidence to brave the situation and make relatively bold choices.

Of course, these were weather savvy travelers—“weather salient,” in the psychological lexicon (see this BAMS paper by Alan E. Stewart for more on this). One wonders how seasoned natives navigated similar choices yesterday and today.

In Oklahoma, at least, the governor didn’t wait long to see what people would do. He closed interstates and state highways:

“I am urging all Oklahomans to take winter storm precautions and stay off the roads unless travel is absolutely necessary,” Gov. Brad Henry said earlier in the day after declaring a state of emergency. “This is a very serious winter storm, and we want Oklahomans to stay safe.”

Perhaps the governor didn’t read Klockow and Peppler’s study. Or maybe he did, and realized that the bar for weather salience this Christmas was a little too high.