The Space Weather Symposium at the AMS Annual Meeting once again will discuss the radiation exposure that airplane passengers get from outer space. This year the presentations in this area of space weather cover future suborbital flights as well (Tuesday, 1:30 p.m., B315).

A typical flight exposes airline passengers to minimal levels of extraterrestrial radiation; such occasional exposures are not considered harmful. The radiation concern is usually reserved for high-flying pilots who spend a lot of time in the air, especially on long polar routes, or for flights during a solar storm.

But one source of gamma rays and typical x-rays might indeed be quite problematic, though very rare, for ordinary air travelers. The radiation is not from outer space, but instead from Earth.

A research group led by Joe Dwyer, professor of physics and space sciences at Florida Institute of Technology, shows that terrestrial gamma-ray flashes (TGFs) produced by thunderclouds could expose nearby airplanes to a radiation dose of 10 rem. That’s about 400 chest X-rays, three CAT scans, or 7,500 hours of normal flight time, what the researchers describe as

News

3, 2, 1…You're On the Air

Yes, this blog is on the air…but it’s about a lot of other subjects, too.

There was a time when meteorology meant all things atmospheric. But that’s not enough anymore. The air we breathe reflects the crops we grow, the cities we build, and the cars we drive. Air picks up water and salt from the oceans, and mixes dust from our barren fields and sand from hostile deserts. It absorbs and relays radiation from above and below, responding to solar eruptions from afar. It mixes all of that and more to make weather.

In short, the air is a convergence of physics, chemistry, biology, sociology, economics—practically every branch of knowledge. Long ago meteorology morphed into “atmospheric, oceanographic, hydrologic, and related sciences” and then it became something even more complicated—bigger and more interconnected.

When you look at the 90-year-old AMS seal, though, what you see is not an enumeration of sciences—physical and social—convening under one big umbrella. Rather, what you see is a circle of applications—public health, engineering, agriculture, commerce, aerial navigation, and so on. Science and service converge on weather.

When you look at the 90-year-old AMS seal, though, what you see is not an enumeration of sciences—physical and social—convening under one big umbrella. Rather, what you see is a circle of applications—public health, engineering, agriculture, commerce, aerial navigation, and so on. Science and service converge on weather.

Isn’t it striking, then, that we keep circling back to that spirit of 1919, the founding of AMS. The theme of the upcoming AMS Annual Meeting is “Weather, Climate, and Society: New Demands on Science and Services.” The Presidential Forum brings together public health and air transportation experts; the meeting also delves into renewable energy and insurance. One of the plenary talks is aptly titled, “A Science of Service.”

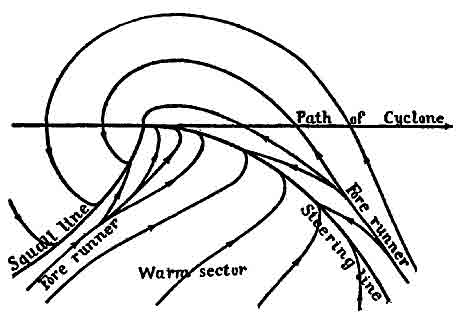

Just weeks after AMS was born, Monthly Weather Review introduced American readers to Jacob Bjerknes’ landmark paper, “On the Structure of Moving Cyclones.” It was part of the scientific revolution in forecasting based on the convergence of airstreams. Ever since, those convergences—“fronts”—have been synonymous with weather, and oceans too.

Fronts and the AMS thus have shared nine decades of mutual history. The Front Page will be informal and spontaneous, like the weather, airing all sorts of perspectives. It is the latest in a long line of everyday convergences of science and service.