Imagine you live in a part of the country where few people have experienced tornadoes. It would make sense that your neighbors wouldn’t know the difference between a tornado watch or warning, or know how to seek safety.

A new, openly available online tool shows exactly that, by combining societal databases with survey results about people’s understanding of weather information. But there are some surprising wrinkles in the data. For example, the database drills down to county-level information and finds “noteworthy differences” within regions of similar tornado climatology.

How is it that Norman, Oklahoma, residents score higher in what people think they know of severe weather information than those in Fort Worth, Texas? And why is there a similar gap between what people actually do know, as tested in Peachtree City, Georgia, versus Birmingham, Alabama?

“Differences like this create important opportunities for research and learning within the weather enterprise,” say Joseph T. Ripberger and colleagues, who describe the weather demographics tool in a recently published Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society article. “The online tool—the Severe Weather and Society Dashboard (WxDash)—is meant to provide this opportunity.”

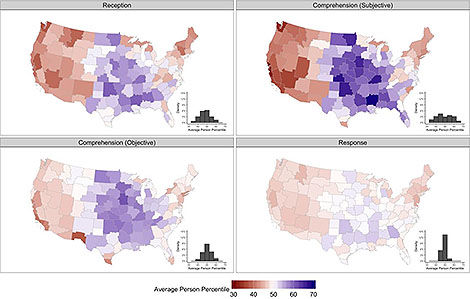

For example, in one key set of metrics, the WxDash website looks at survey data on how well people receive and pay attention to tornado warnings (reception), how well they understand that information (both “subjective” comprehension—what people think they know—and “objective” comprehension—what they actually know), and response to tornado warnings.

WxDash combines U.S. Census data with an annual Severe Weather and Society Survey (Wx Survey) by the University of Oklahoma Center for Risk and Crisis Management. The database then “downscales” the broader scale information to the local level, in a demographic equivalent to the way large scale climate models downscale to useful information on regional scales.

The site also provides information on public trust in weather information sources, perceptions about the efficacy of protective action, vulnerability to beliefs about a variety of tornado myths, and other weather-related factors that can then be studied in light of regional and demographic factors.

Some of the key findings seen in the database:

- Men and women demonstrate roughly comparable levels of reception, objective comprehension, and response, but men have more confidence in subjective warning comprehension than women.

- Tornado climatology has a relatively strong effect on tornado warning reception and comprehension, but little effect on warning response.

- The findings suggest that geography, and the community differences that overlap with geographic boundaries, likely exert more direct influence on warning reception and comprehension than on response.

Even the relatively expected relation of severe weather climatology to severe weather understanding is problematic, Ripberger and colleagues write.

Tornadoes are possible almost everywhere in the US and people who live on the coasts can move—both temporarily and permanently— throughout the country. These factors prompt some concern about the low levels of reception and comprehension in some communities, especially those in the west.

In addition to interacting with these data, you can download one of the calculated databases for community-scale information, the raw survey data, and the code necessary to reproduce the calculations.

The idea is social scientists can dig in and figure out why what we know about weather isn’t nearly as closely correlated with what we experience as we might think. The hope is an improvement in public education and risk communication strategies related to severe weather.