While the ranks of women weathercasters are growing slowly, they continue to lag behind their male colleagues in job responsibilities.

A new study to be published in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society shows that 29% of weathercasters in the 210 U.S. television markets are female. This percentage has roughly doubled since the 1980s.

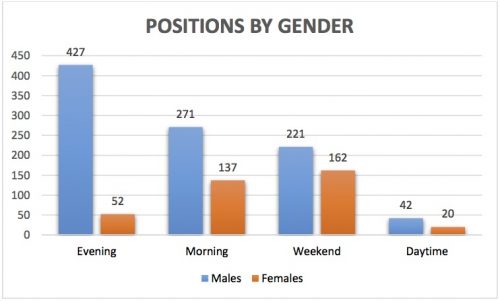

Despite this progress, only 8% of chief meteorologists are female. Meanwhile, 44% of the women work weekends while 37% work mornings. Only 14% of the women work the widely viewed evening shifts.

Last year, 11% of evening or primetime weathercasters were female. That’s only about one-third the percentage reported in a study published in 2008, suggesting a possible decline in female representation in this high-profile broadcast slot.

Educational levels were gender dependent, as well. While 52% of the women had meteorology degrees, 59% of the men did.

Alexandra Cranford of WWL-TV in Slidell, Louisiana, the author of the new study, gathered her data in 2016 from TV station websites. The biographical information was compiled for 2,040 weathercasters, making the study the largest of its kind. Because it relied on self-reported, publicly available information, Cranford suggests that there may be some underrepresentation of various factors: online bios tend might tend to omit information that makes broadcasters look less qualified or experienced. The bios on males were somewhat less likely to omit their exact position at the a station, while the bios on females were somewhat less likely to omit education information.

Previous studies have shown that viewers tend to perceive men as more credible and thus more suited for a variety of broadcast roles, from serious news situations to commercial voice-overs. This perception was one of the motivations for Cranford’s study and may be weighing on hiring and assignment practices for weathercasters. In the article, Cranford notes that past research had indicated,

Constructs including the “weather girl” stereotype and gender-based differences in perceived credibility could potentially contribute to the percentage of women in broadcast meteorology remaining low, especially in chief and evening positions.

Based on the new data, Cranford concludes,

Additional research should explore if factors such as persistent sexism in hiring practices or women’s personal choices could explain why fewer female weathercasters have degrees and why women work weekend shifts while remaining underrepresented in chief meteorologist and evening positions.