While a major winter storm last month was plastering the United States from Texas and New Mexico to New England with heavy snow and ice, volatile conditions in the Southeast (SE) spawned damaging and deadly tornadoes. One of these overnight Monday, February 16, tragically took the lives of 3 people and injured 10 in coastal North Carolina. Such nocturnal tornadoes are common in the Southeastern U.S.—a unique trait—and represent an extreme danger to sleeping residents.

From the first 🌪️🌪️ in #flwx & #gawx to the #tornado preliminarily rated EF3 in #ncwx — radar imagery and CAPE pic.twitter.com/Ow02xSwlaP

— Stu Ostro (@StuOstro) February 16, 2021

Compounding this problem, new research in the AMS journal Weather, Climate, and Society suggests there may be a deadly disconnect between tornado perception and reality in the region right when residents instead need an acute assessment of their tornado potential.

The article “Do We Know Our Own Tornado Season? A Psychological Investigation of Perceived Tornado Likelihood in the Southeast United States,” by Stephen Broomell of Carnegie Mellon University, with colleagues from Stanford and NCAR, notes the tragic results of the regional misperception:

The recurring risks posed by tornadoes in the SE United States are exemplified by the significant loss of life associated with recent tornado outbreaks in the SE, including the 2008 Super Tuesday outbreak that killed over 50 people and the devastating 27 April 2011 outbreak that killed over 300 people in a single day.

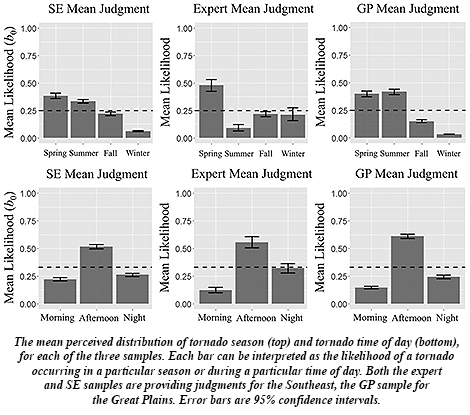

Their survey of residents in seven states, from Louisiana and Arkansas to Georgia and Kentucky, representing the Southeastern region, finds that the residents perceive their tornado likelihood differently than meteorologists and experts familiar with Southeastern tornado risk. This puts them at great risk because residents’ experiences don’t match what actually happens where they live.

Broomell and his fellow researchers contend that Southeast residents may be misusing knowledge of Great Plains tornado events, ubiquitous in tornado chasing reality shows and social media videos, when determining their own risk. A fatal flaw since tornado behavior is different between the two regions.

For starters, unlike in infamous “Tornado Alley” states of Texas and Oklahoma north through Nebraska and Iowa into South Dakota, the Southeast lacks a single, “traditional” tornado season, with tornadoes “spread out across different seasons,” Broomell along with his coauthors report, including wintertime. The Southeast also endures more tornadoes overnight, as happened last week in North Carolina. And they spawn from multiple types of storm systems in the Southeast, more so than in the Great Plains. This makes knowledge about residents’ regional tornado likelihood especially critical in Southeastern states.

For starters, unlike in infamous “Tornado Alley” states of Texas and Oklahoma north through Nebraska and Iowa into South Dakota, the Southeast lacks a single, “traditional” tornado season, with tornadoes “spread out across different seasons,” Broomell along with his coauthors report, including wintertime. The Southeast also endures more tornadoes overnight, as happened last week in North Carolina. And they spawn from multiple types of storm systems in the Southeast, more so than in the Great Plains. This makes knowledge about residents’ regional tornado likelihood especially critical in Southeastern states.

Another recent study published in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, “In the Dark: Public Perceptions of and National Weather Service Forecaster Considerations for Nocturnal Tornadoes in Tennessee,” by Kelsey Ellis (University of Tennessee, Knoxville), et al., surveyed residents of Tennessee and came away with similar findings about tornado timing: about half of Tennessee’s tornadoes occur at night, and yet less than half of those surveyed thought they would be able to receive nighttime tornado warnings.

Local forecasters and broadcast meteorologists as well as emergency managers are tuned into the mismatch. In the BAMS study, NWS forecasters said they fear for the public’s safety, particularly with nighttime tornadoes, because they “know how dangerous nocturnal events are”—fatalities “are a given,” some said.

Ellis and her colleagues recommended developing a single, consistent communication they term “One Message” to focus on getting out word about the most deadly aspect of the tornado threat. Forecasters, broadcasters, and emergency managers through regular and social media would then be consistent in their messaging to residents, the researchers state, decreasing confusion. For example:

Nighttime tornadoes expected. Sleep with your phone ON tonight!

With severe weather season ready to pop as spring-like warmth quickly overwhelms winter’s icy grip in the next couple of weeks, the nation’s tornado risk will blossom across the South and Southeast. And nocturnal tornado threats will only increase, particularly in the Southeast, as February turns into March, and then April—a historically deadly month.

For residents in places more prone to nighttime tornadoes, Ellis et al. say the ways to stay safe are clear:

Have multiple ways to get tornado warnings, do not rely on outdoor sirens, sleep with your phone on and charged during severe weather, and do not stay in particularly vulnerable locations such as mobile homes or vehicles.