The 2017 Atlantic hurricane season has begun. If they haven’t already, people who could be affected by tropical storms and hurricanes should prepare now for the six-month season, which ends November 30 and encompasses the Atlantic Ocean, Caribbean Sea, and Gulf of Mexico.

The 2017 Atlantic hurricane season has begun. If they haven’t already, people who could be affected by tropical storms and hurricanes should prepare now for the six-month season, which ends November 30 and encompasses the Atlantic Ocean, Caribbean Sea, and Gulf of Mexico.

Here’s what you need to know. Follow the links for more detailed information:

What’s New

Two new products this year will be issued by the National Hurricane Center in addition to the typical tropical storm and hurricane watches, warnings, and advisories:

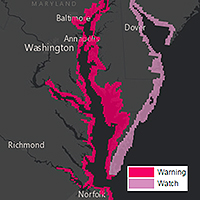

Storm surge watches will be issued within 48 hours of possible life-threatening coastal inundation. Storm surge warnings will be issued at least 36 hours before the danger of life-threatening coastal inundation is realized. The new graphical products will be issued in tandem with NHC’s Potential Storm Surge Flooding Map, which quantifies the expected inundation from storm surge and indicates the depth of the flooding on land.

Storm surge watches will be issued within 48 hours of possible life-threatening coastal inundation. Storm surge warnings will be issued at least 36 hours before the danger of life-threatening coastal inundation is realized. The new graphical products will be issued in tandem with NHC’s Potential Storm Surge Flooding Map, which quantifies the expected inundation from storm surge and indicates the depth of the flooding on land.- Potential tropical storms and hurricanes growing out of disturbances that have not yet become tropical depressions or storms but that pose the threat of bringing tropical storm or hurricane conditions to land areas in 48 hours will be treated as regular storms, with NHC issuing watches, warnings, advisories, and related graphical products as needed.

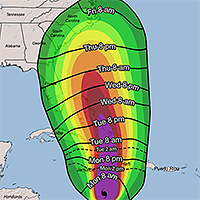

Additionally, NHC will introduce a map to provide guidance on when users should have their preparations completed before a storm. These experimental graphics will show Time of Arrival of Tropical-Storm-Force Winds—a critical planning threshold for coastal communities. Many preparations become difficult or dangerous once tropical storm conditions begin.

Additionally, NHC will introduce a map to provide guidance on when users should have their preparations completed before a storm. These experimental graphics will show Time of Arrival of Tropical-Storm-Force Winds—a critical planning threshold for coastal communities. Many preparations become difficult or dangerous once tropical storm conditions begin.

Prepare

People living in states bordering the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico, as well as in The Bahamas, Bermuda, and Caribbean islands, should know that water could be a life-threatening hazard when a hurricane hits. This threat includes storm surge—the sudden rise of seawater at the coast near and to the right of where a hurricane’s center makes landfall. In the United States, hurricane evacuation maps account for the flooding from storm surge and show areas along the coast that people should evacuate if a hurricane threatens. Or it could be from freshwater flooding triggered by a storm’s torrential rain. If either is a risk, make a plan now to leave when threatened.

If water is not a risk, and your area will only face the threat of strong, damaging winds, the official recommendation from the National Hurricane Center is to shelter in place. Meaning, stay put—rather than evacuate. But stay only if your residence is sufficient to weather the storm. Now is the time to prepare your home and property for the possibility of high winds and heavy rain.

Forecasts

A wide variety of academics, private forecasting companies, and the U.S. government issue seasonal hurricane predictions. They generally tend to agree, particularly when a season is expected to be well above or below average. But this year could be a bit different with some predicting fewer tropical storms and hurricanes than is typical in an average year, and others predicting more than the usual numbers of storms and hurricanes. An average Atlantic hurricane season sees a dozen named storms, with a half-dozen of these becoming hurricanes and two going on to become major hurricanes with sustained winds greater than 110 mph.

A quick look at the five longest-running seasonal forecasts for named storms, hurricanes, and major hurricanes, respectively:

- NOAA 11-17, 5-9, 2-4 (midpoints of each range yield 14,7,3) [issued May 25, 2017]

- Colorado State University 14,6,2 [updated June 1, 2017, from 11,4,2]

- The Weather Company 14,7,3 [updated May 22, 2017, from 12,6,2]

- Tropical Storm Risk 14,6,3 [updated May 26, 2017, from 11,4,2]

- Penn State 11-20 named storms with a best estimate of 15 [issued April 25, 2017]

The reason for the low numbers in those forecasts with ranges: there’s uncertainty about whether another El Niño may form midway though the season—El Niño is an anomalous warming of the eastern tropical Pacific that causes air to rise and spread out there, creating wind shear over the Atlantic that inhibits tropical development—as well as whether warmer-than-usual sea surface temperatures in the tropical Atlantic favorable for development will remain that way or cool through the season. Increasing numbers in several forecasts updated since earlier in the spring seem to indicate a lower likelihood of both, although forecasters caution they could reduce the numbers if more than a weak El Niño develops and Atlantic SSTs consequently cool.

Bottom Line

Nearly every weather entity states what Acting FEMA Administrator Robert J. Fenton, Jr. recently expressed after NOAA released its hurricane season forecast last week: “Regardless of how many storms develop this year, it only takes one to disrupt our lives.”

The advice of hurricane forecasters and emergency managers alike is to prepare early and as if this will be the year your neighborhood is hit.

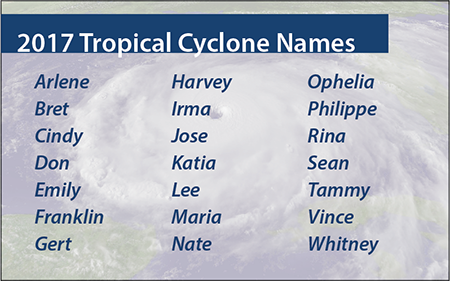

Storm Names

If this year’s list of names the National Hurricane Center will use to keep track of Atlantic storms seems familiar, it’s because it is. NHC made it all the way through this list in the 2005 season. The names of five memorable and deadly hurricanes that year were retired: Dennis, Katrina, Rita, Stan, and Wilma. The updated list was used again in 2011, since NHC rotates through six sets of names, and Irene that year also was retired and replaced.