Derechos are less common than Midwestern tornadoes, but occur almost every year in that region as well as other parts of the United States. Yet they remain exotic and mystifying. Even to meteorologists.

The reason appears to lie in the complex way the long-lived windstorms form. Derechos are often incorrectly referred to as inland hurricanes; their damaging winds can reach hurricane force, but they are straight-line in nature, rather than circulating around a common center. When people suffer, though, they can be forgiven for using the wrong windstorm term. By definition derechos have to meet specific criteria, such as causing damage continuously or intermittently in a lengthy line of at least 400 miles that’s at least 60 miles wide. But just like hurricanes, they come in a variety of intensities.

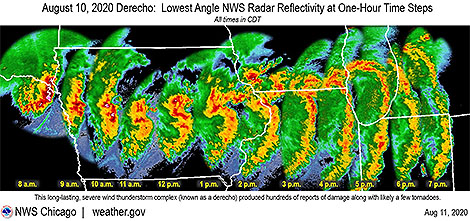

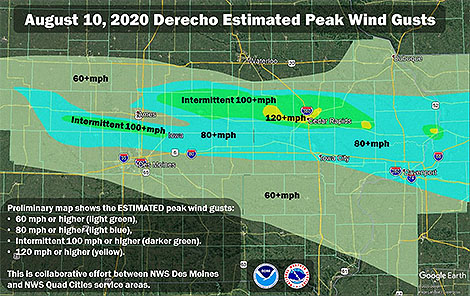

Last week’s derecho, roaring 750 miles from eastern Nebraska across Iowa, Illinois and Indiana, was particularly ferocious with winds in multiple swaths across Iowa gusting to over 100 mph. The National Weather Service found damage to an apartment complex in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, consistent with wind gusts of an astonishing 130-140 mph. But even these extreme winds and the severe damage they wrought don’t tell the whole story of the variation in these windy storms with the seemingly odd name.

Last week’s derecho, roaring 750 miles from eastern Nebraska across Iowa, Illinois and Indiana, was particularly ferocious with winds in multiple swaths across Iowa gusting to over 100 mph. The National Weather Service found damage to an apartment complex in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, consistent with wind gusts of an astonishing 130-140 mph. But even these extreme winds and the severe damage they wrought don’t tell the whole story of the variation in these windy storms with the seemingly odd name.

The AMS Glossary of Meteorology states: “The term derecho derives from a Spanish word that can be interpreted as “straight ahead” or “direct” and was chosen to discriminate between wind damage caused by tornadoes, which have rotating flow, from straight-line winds.” It defines derechos as widespread convectively induced straight-line windstorms.

The AMS Glossary of Meteorology states: “The term derecho derives from a Spanish word that can be interpreted as “straight ahead” or “direct” and was chosen to discriminate between wind damage caused by tornadoes, which have rotating flow, from straight-line winds.” It defines derechos as widespread convectively induced straight-line windstorms.

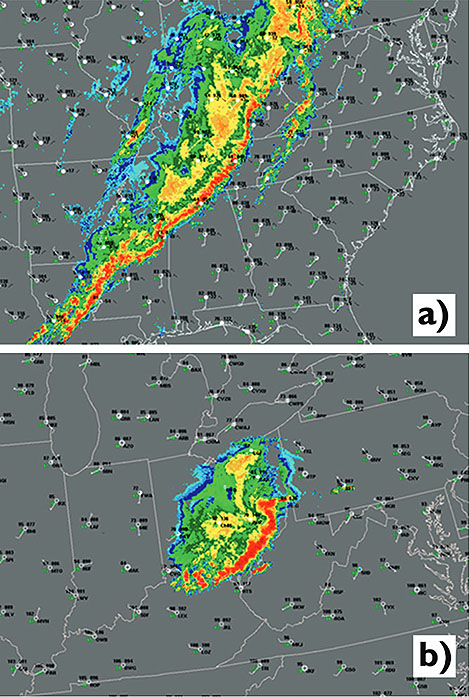

Specifically, the term is defined as any family of particularly damaging downburst clusters produced by a mesoscale convective system. Such systems have sustained bow echoes with book-end vortices and/or rear-inflow jets and can generate considerable damage from straight-line winds.

http://spc.noaa.gov/misc/AbtDerechos/casepages/apr042011page.htm and

http://spc.noaa.gov/misc/AbtDerechos/casepages/jun292012page.htm.

This updated definition was the work of a team of meteorologists about five years ago who compared different straight-line windstorms—all meeting the damage criteria of derechos at the time but clearly having different mechanisms driving them. Their published paper in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society was “A Proposed Revision to the Definition of ‘Derecho’.” With it, the authors made the case to improve the definition of derecho to make it more physically based and more closely mirror other definable meteorological terms such as tornadoes, extratropical cyclones, and cirrus clouds.

While the paper had a positive effect among the meteorological community, a web search still turns up different definitions of derecho among meteorological websites, including within the NWS.

We asked the lead author of the BAMS paper, Stephen Corfidi (NOAA NWS, CIMMS, University of Oklahoma), for his thoughts on last week’s Midwestern derecho, to put it in perspective and also to help explain the reasons behind the difficulty with meteorologists not only defining but using the meteorological term differently.

BAMS: Was last week’s Midwest fast-moving line of severe thunderstorms with damaging winds a derecho? If so, did it fit the Glossary definition of a derecho?

Stephen Corfidi: Last Tuesday’s Midwest wind storm met the AMS Glossary definition of a derecho. Most significantly, it satisfied the criterion for the presence of “one or more sustained bow echoes with mesoscale vortices and/or rear-inflow jets.” A large mesoscale vortex, located on the north end of the larger-scale bow-shaped convective system from central Iowa to Lake Michigan, appears to have been associated with some of the strongest and longest-duration surface winds that accompanied the event. While the swath of organized damaging winds was not particularly long (on the order of 500 miles (800 km)) in comparison to some past events, the length well exceeded the somewhat flexible 400-mile (~ 650 km) cut-off used to distinguish derecho storms.

BAMS: Among derechos, how does this one rank?

SC: The Iowa-Illinois storm is certainly one of the most memorable of 2020—a year that already has seen other noteworthy events (e.g., those in Colorado, the Dakotas, and Pennsylvania in June). What made the Iowa-Illinois event especially noteworthy was the sizable number of reliably-observed significant surface gusts. There were numerous reports in excess of 80 mph (35 meters/second), and incidental evidence that some locations experienced speeds greater than 100 mph (45 m/s). The strong winds—likely enhanced by the presence of the mesoscale vortex—in some places persisted for more than 30 minutes. The vortex to some extent resembled the “warm-core” (hurricane-like) circulation that formed within the Kansas-Missouri-Illinois derecho of 8 May 2009.

BAMS: What made this one stand out?

SC: The duration of the storm’s high winds over eastern Iowa and western Illinois—again, likely due in part to the presence of the large mesoscale vortex—was certainly outstanding. This is quite a statement considering that the event occurred in a region known for its propensity for derechos (Recall that Gustave Hinrich’s nineteenth century studies of straight-line wind events were based in Iowa).

BAMS: Why are derechos so perplexing and difficult for meteorologists to acceptably define?

SC: There are several reasons why derechos are not only difficult to define, but also challenging to forecast. Unlike supercell thunderstorms that, in most cases, are well-delimited in time and space, broad swaths of damaging convective winds can arise in many different ways. Some of the processes involved in derecho development remain poorly understood and / or are only partly resolved by current observational platforms.

More significantly, unlike weather phenomena like supercells, derechos may or may not be accompanied by meteorological structures that readily are apparent to human observers. For example, most meteorologists recognize a supercell when one appears in the sky. But specific cloud formations are not associated with derechos, and the characteristic meteorological structures that do accompany many derechos (e.g., embedded vortices and rear-inflow jets) are too large or subtle to be recognized by human observers without the aid of remote-sensing devices such as radar and satellite.

These same aspects make derechos difficult to forecast. One can say that derechos arise when a unique combination of known and unknown necessary ingredients is present over a sufficiently broad area to support rapid, repetitive, downshear thunderstorm development. That said, applying this concept in practice presents a formidable challenge. In some cases, the known ingredients are present, but the extent of the favorable environment is too limited for derecho status to be realized. Conversely, expansive environments sometimes appear that are supportive of widespread destructive winds, but not those strongly dependent on the smaller-scale processes associated with rear-inflow jets and mesoscale vortices.

As with any weather forecast, when “missed” derecho events occur, the root causes can be traced to the existence of too many unknowns—both observational and theoretical. In the case of derechos, both unknowns, at present, remain sizable.

BAMS: What has been the impact of your 2016 BAMS paper and proposed new definition?

SC: It does appear that the updated definition proposed in the paper has been adopted to at least some extent in the severe weather community; the updated definition in the AMS’ Glossary likely abetted the effort. There is, of course, no “official” arbiter of general meteorological terms. This explains, in part, the range of derecho “definitions” that appear in some sources. The lack of consistency in the use of the term “derecho” was, in fact, a motivating factor in drafting the paper. We’d like to think that the paper focused needed attention on the value of increased precision in meteorological terminology, but that is not something that is easy to measure. It is probably safe to say that the definition of “derecho” will continue to change as the underlying processes responsible for the most intense storms become better understood.

BAMS: What would you like readers of your 2016 paper to learn about and from the re-defining of derecho?

SC: I think perhaps the most important take-aways are that (1) the existing definition was outdated because of the significant changes that have occurred in observational data, record-keeping, and understanding since the mid-1980s, and (2) that if we are to better understand and forecast high-wind-producing convective systems, we need to first better classify those systems that are observed.

BAMS: You and your colleagues at NOAA-NWS-NCEP put together a comprehensive and impressive website About Derechos. How did you become interested in them?

SC: Convective systems, in general, are interesting because there are so many “moving parts” involved in their development, sustenance, and motion. It is especially challenging—but also rewarding—to try to assess the strength and likely longevity of those processes in real-time so as to prepare useful forecasts. Derechos are high-impact events; they are one area where society would benefit greatly from increased meteorological knowledge.

BAMS: What was the biggest challenge you encountered in your work to update the derecho definition?

SC: Having thoughts on introducing any new idea is one thing, but putting those concepts into words is another. Unlike most other papers in our “business,” in this one I felt we had to be somewhat persuasive. I was not at first comfortable with taking such an approach. But the contrasts presented by the two derecho events introduced in the first part of the paper furthered my conviction that persuasion was needed to both defend and encourage discussion on the definition topic.

BAMS: What got you initially interested in meteorology?

SC: My interest in clouds and storms goes back to my earliest days as a young kid growing up in a house kept super-clean by my mom. Because I was forbidden to play in the yard when the grass was wet (I’d track dirt into the house, of course!), I soon came to appreciate “Mr. Sun.” In particular, I noticed that I’d often not see the sun the next day if certain cloud formations had appeared in the sky on the previous one. A bit later, in first grade, my dad introduced me to weather books in the local library. Some had cloud pictures indicating which formations were “bad,” and which were associated with good weather. I was hooked! Thunderstorm days were always a favorite because the clouds on such days seemed to change the most rapidly—and provided the most surprises. I was very interested in things like rocks and plants, too—but weather was always #1.

Your article states that “The National Weather Service in Des Moines found damage to grain storage bins consistent with wind gusts of an astonishing 130-140 mph”.

I believe this was actually NWS Quad Cities area and those winds were estimated that high (130-140 mph) due to damage to an apartment complex in Cedar Rapids, IA and to a radio transmission tower that collapsed (130 mph) near Marion and Clinton (see NWS Quad Cities Overview section: https://www.weather.gov/dvn/summary_081020)

Thanks for the information, Andrew…we’ve corrected the post.