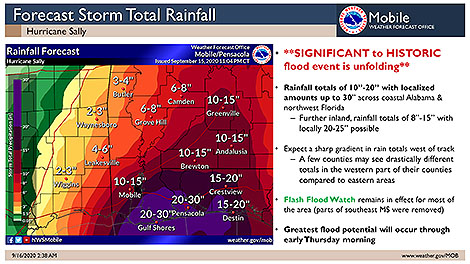

Hurricane Sally is inching ashore in southeast Alabama Wednesday morning and has started to flood parts of the central Gulf Coast with an expected 1-2 feet of rain, maybe more. With that much rain forecast, it seems likely to join other recent catastrophic flood disasters Harvey (2017) and Florence (2018) in ushering in a new era of rainier storms at landfall that bring with them an extreme rain and flooding threat.

Recent research by NOAA’s Tom Knutson and a team of tropical weather and climate experts in the March Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society and blogged about here determined with medium-to-high confidence that more and more hurricanes in our future warming world will be wetter at landfall.

And with more wetter storms on the way, better communication about these potentially deadly impacts from copious rainfall is needed. Another BAMS article we blogged about addressed this by creating an Intuitive Metric for Deadly Tropical Cyclone Rains. Its authors designed the new tool—the extreme rainfall multiplier (ERM)—to easily understand the magnitude of life-threatening extreme rain events.

Co-author James Kossin explained to BAMS:

Water presents a much greater hazard in a hurricane than wind does, but the Saffir-Simpson categories are based on wind-speed alone. Salt-water hazards along and near the coast are caused by storm surge. Coastal residents are warned about these hazards and are provided with evacuation plans. Fresh-water flooding from extreme hurricane rainfall, however, can happen inland away from evacuation zones, and pose the greatest threat to life and property in these areas where people tend to shelter-in-place. Compound hazards such as dam failures and land-slides in mountainous regions pose additional significant threats. In this case, effective warnings and communication of the threats to inland populations is paramount to reduce mortality. This work strives to present a tool for providing warnings based on people’s past experience, which gives them a familiar reference point from which to assess their risk and make informed decisions.

Lead author Christopher Bosma:

We started out this project focused on analyzing the catastrophic and record-breaking rainfall associated with Hurricane Harvey. But, as we started to finish our analysis of that system, just a year later, Hurricane Florence brought devastating and torrential rainfall to the Carolinas, which forced us to go back and revisit some of our initial analysis. The fact that multiple major storms happened in quick succession grabbed a lot of headlines, but, from a research and scientific perspective, it also provided a chance to note how the messaging used to describe these systems had changed (or not) and think of other ways to use the metric we had developed.

ERM is not yet operational, but that is the researchers’ goal, to “convey effective warnings to people about fresh-water flooding threats,” Kossin says.

Hurricane Sally is one such extreme rainfall flood threat, with “significant to historic flooding” likely, the National Weather Service says.

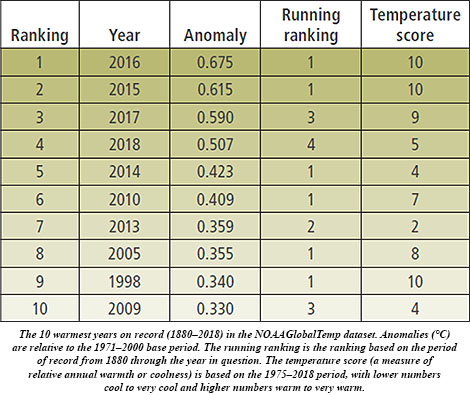

The temperature score from 1 (a very cold year) to 10 (very warm) is useful to distinguish between warmer and colder years relative to the long-term trend. As examples, the authors note that 2008 and 2011 were considerably cooler than surrounding years and below the overall trend, whereas 1998 and 2016 were not only the warmest years on record but were also notably warmer than surrounding years.

The temperature score from 1 (a very cold year) to 10 (very warm) is useful to distinguish between warmer and colder years relative to the long-term trend. As examples, the authors note that 2008 and 2011 were considerably cooler than surrounding years and below the overall trend, whereas 1998 and 2016 were not only the warmest years on record but were also notably warmer than surrounding years. BAMS: What would you like readers to learn from your study of record global temperatures?

BAMS: What would you like readers to learn from your study of record global temperatures?