A session spotlight from the 31st Conference on Severe Local Storms

By Katie Pflaumer, AMS Staff

The session “Perception and Risk Associated with Severe Weather” at the 31st Conference on Severe Local Storms highlighted the interactions between severe weather and societal impacts. Here are a few takeaways.

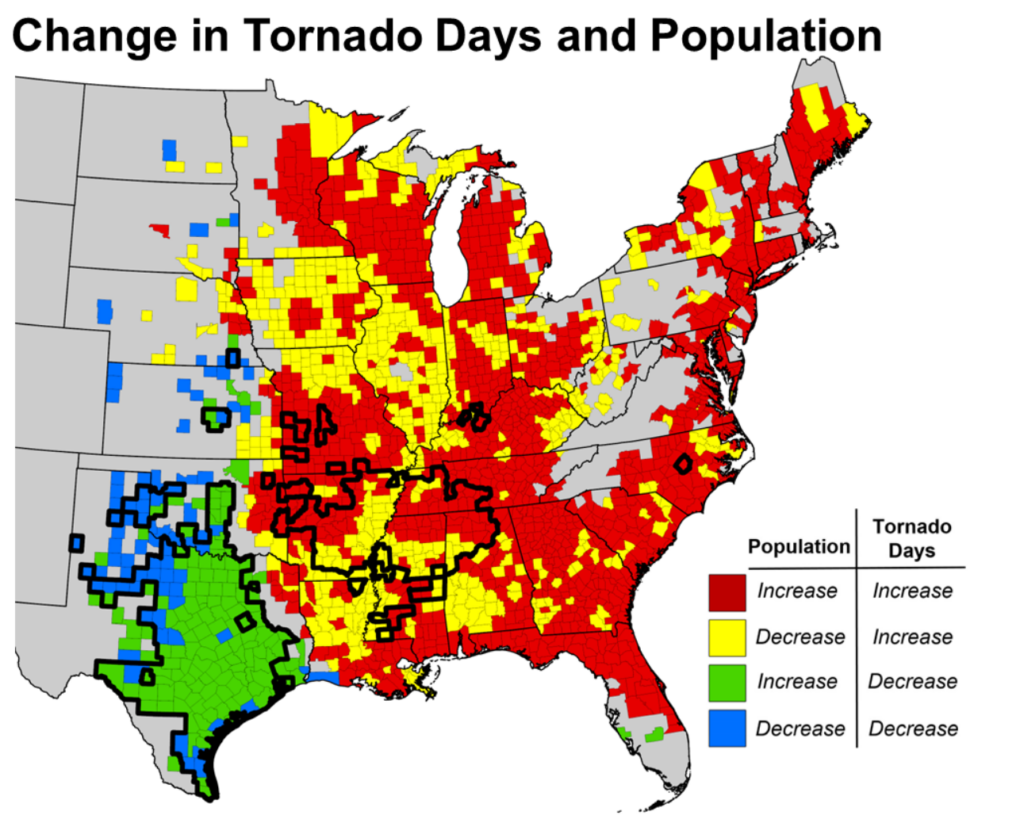

Tornado impacts are increasing across the United States–despite variation in where tornadoes hit. A presentation by Stephen Strader (Villanova University) highlighted the importance of considering all factors to understand tornado impacts, not just climate. Using 40 years of observational data, plus a statistical model depicting changes in societal factors, researchers found that increased housing and population growth in tornado-prone areas is a key driver of increased tornado damage/human risk.

While the number of days with tornadoes is trending down in the U.S. Southern Plains and trending upward in the mid-South; the likelihood of tornado damage has increased in both regions due to increased human occupation. However, the combination of tornado increases with population growth and spread has tripled tornado impact potential in the mid-South since 1980, surpassing the Southern Plains. Strader noted that stricter enforcement of building codes, investments in tornado shelters and safe rooms, and public education could help mitigate tornado damages–if scientists can get across the message that human factors matter.

“We have to get away from this idea that climate change is a cause of a disaster … climate change is a contributor to a disaster, not a cause. [Disaster] is inherently linked to societal factors. … With environmental changes and exposure changes/housing growth, you see an increasingly disaster-prone society.”

—Stephen Strader

Graphic from: Strader, S.M., Gensini, V.A., Ashley, W.S., and A.N. Wagner (2024) “Changing Tornado Environments Vs. Changing Societal Vulnerability and Exposure.” (Poster presented at 31st Conference on Severe Local Storms, October 21.) Originally from Strader et al. (2024), “Changes in tornado risk and societal vulnerability leading to greater tornado impact potential.” NPJ Natural Hazards, 19 June. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44304-024-00019-6

Wireless Emergency Alerts are critical—and confusing—for Spanish speakers in the U.S. Southeast. A study presented by Joseph Trujillo-Falcón (University of Illinois) found that Spanish-language wireless emergency alerts (WEAs, phone notifications about severe weather) from the National Weather Service are crucial safety tools. For some tornado survivors in Kentucky, for example, the WEA had been their only trigger to get to safety. In-depth conversations with 27 Spanish speakers from across the U.S. found that WEAs were highly respected and useful, yet needed some redesign to avoid confusion. For example, the Spanish translation of the NWS acronym (SNM) called to mind medical conditions or kink. The word “proyectiles” (projectiles), used to warn about airborne debris, evoked war zone imagery rather than weather. Using the word “aviso” for “warning” struck many as less urgent than the term “alerta.” In addition, 360-word warnings (versus those of 90 words or less) helped readers better understand what was going on and what to do in response. This was especially important for people who hadn’t encountered a tornado in their country of origin. Direct links to information and instructions on how and where to shelter were also seen as key, especially in areas with many mobile or manufactured homes.

“The information source that I take most seriously as a recently arrived immigrant are WEAs. Since everyone gets it at the same time, if one ignores it, the other reads it.”

—Gabriela, Venezuelan immigrant who has limited English proficiency (Trujillo-Falcón 2024).

People want different forecast information as a threat evolves. A study presented by Makenzie Krocak (National Severe Storms Laboratory) analyzed data from the Severe Weather and Society survey to determine what information members of the public want and need at different times in relation to weather threats. They found that respondents’ priorities changed over time. In longer time frames (e.g., three days in advance) survey respondents overwhelmingly ranked location information and event probability as the most valuable information; people wanted to know, ‘Should I prepare for severe weather to occur in my area?’ A day to an hour in advance, people wanted to know about the timing of the event, as well as its potential severity. In the warning time frame (60 minutes or less) their desire for information about potential impacts and necessary protective actions increased.

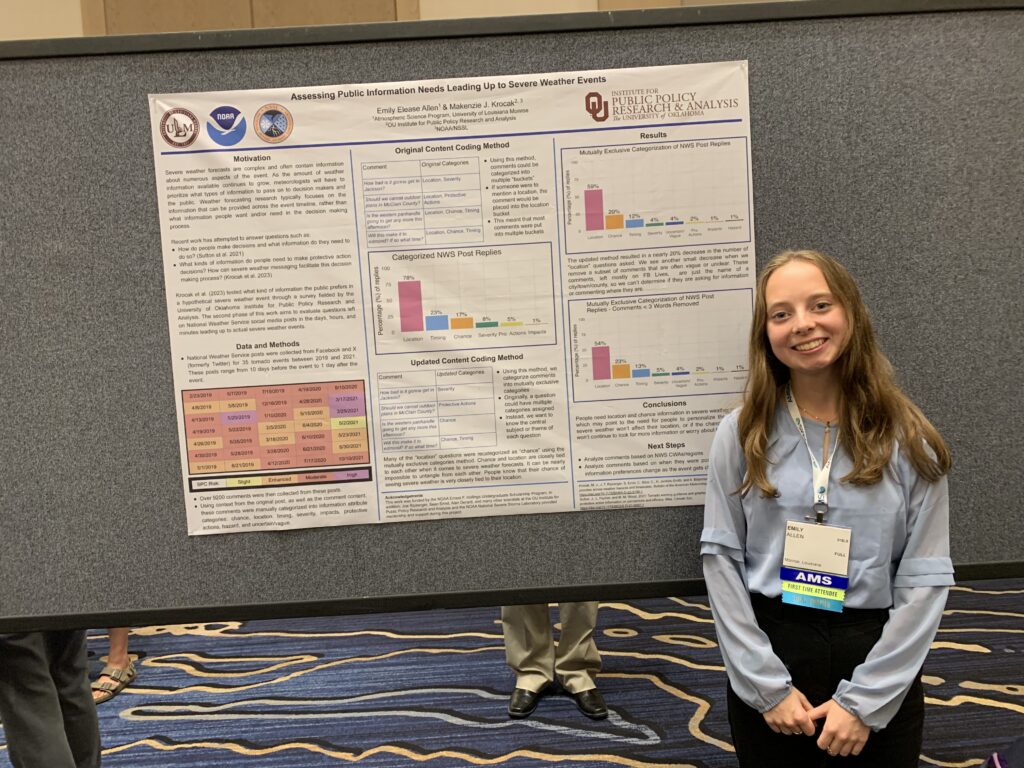

For additional insight, the researchers painstakingly categorized, geo-located, and analyzed 9000+ social media comments from the National Weather Service Facebook and Twitter/X accounts before and after severe weather events. A poster presented by undergraduate student Emily Allen (University of Louisiana Monroe) delved into this side of the equation.

Three days out from an event, commenters largely asked about the chance of an event happening, but for nearer time frames, location became the dominant question—i.e., ‘Will this hit my specific area?’ Krocak emphasized the need to include very clear landmarks in warning graphics to help people find their location. She also noted that certain groups still require information about protective actions to take—especially those with the least experience dealing with a particular hazard.

Making severe weather products usable and understandable. Two presentations dealt with public perceptions of evolving probabilistic weather forecast information—that is, communicating changes in severe weather risks across time and geography.

Christopher Wirz (NSF NCAR) presented preliminary results of a study about public perceptions of evolving probabilistic tornado forecasts and warnings. On average, respondents’ sense of risk was about the same as for a deterministic (e.g., warning vs no-warning) forecast; most were likely to be on high alert during a tornado warning in any case, and not underestimate their risk. However, there were differences in how participants responded based on where they were located relative to a given warning polygon. For example, some felt they were in more danger if they were ‘in front’ of the warning polygon, despite the graphics showing equal tornado risk in other directions. Warn-on forecasts—alerts issued when a significant risk is predicted, often long before a tornado is detected by radar—were seen as less actionable by some, but others appreciated knowing to ‘keep an eye out.’ Overall, the study found that members of the public don’t take probabilistic information at face value—rather, they interpret it based on context, including existing local knowledge and other warning products they encounter. In addition, for half of the respondents, level of trust in a forecast didn’t change when they received more/updated information, because trust was instead based on how much they trusted the source of the forecast.

Kristin Calhoun (NOAA National Severe Storms Laboratory) presented about new products and communications that are in development to help NWS forecasters and emergency managers use storm-based probabilistic hazard information (PHI) in the severe weather watch-warning timeframe. These included PHI tools layered with threats-in-motion (TIM) information, in which warning polygons are moved (and removed) with the motion of the storm, helping downstream areas prepare sooner and allowing those for whom danger has passed to redeploy their resources more strategically; potential new protocols for the NOAA/NWS Storm Prediction Center, rather than local weather forecast offices, to add or remove an area from a watch/warning once the threat has passed; a blended PHI plus warn-on forecast product that can help emergency managers plan better by seeing storms in motion along with trends in likelihood and potential impact; and a new product based on SPC’s ‘Mesoscale Discussions,’ created by local NWS forecasters and called ‘Local Discussions,’ with an increased focus on potential impacts, timing, and location of hazards versus highly technical information.

Social pressure may impact campus tornado safety. Alicia Klees (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign) presented work conducted largely by undergraduate student Kyla Wolski that has implications for student safety. The University of Illinois’s Illini-Alert system warns students when tornado threats are approaching; most students are aware of the alerts, and most have experienced a tornado warning before. Students were asked in a survey what they would do if they were in a vulnerable location—such as a fourth-floor classroom with glass windows—and received a tornado warning. 75% said they would change their location to seek shelter. However, when a hypothetical professor kept teaching through a tornado warning (as some faculty reportedly did during the last real tornado warning on campus), 22% of students who had planned to seek shelter said they would probably stay in class. These students said they trusted the professor’s judgment—yet professors do not receive extensive formal training on tornado safety. Klees recalled an anecdote from a student in which one faculty member remarked, “I don’t hear the sirens anymore, so it’s fine.”

In addition, most students did not view tornadoes as a major risk, and most were unaware that tornadoes could happen at any time of year. Klees identified future collaborations with Emergency Management to survey faculty and TAs on tornado warning response, with the goal of keeping students safe.

If you are registered for the 31st Conference on Severe Local Storms, you can view the full session recording at this link.

About the 31st Conference on Severe Local Storms

The American Meteorological Society’s 31st Conference on Severe Local Storms takes place 21-25 October, 2024, in Virginia Beach, VA, and online. The conference is the premiere gathering for scientists, forecasters, educators, and communicators engaged in all aspects of work related to hazardous deep convective weather phenomena. Attendees present and discuss cutting-edge research regarding the analysis, prediction, communication, and theoretical understanding of the structure and dynamics of severe thunderstorms, including their associated hazards of tornadoes, damaging winds, large hail, lightning, and flash floods. View the conference program here.