Planetary, synoptic, meso-alpha, meso-beta, local, and more—there are atmospheric scales aplenty discussed at AMS meetings. Enter microtopography, a once-rare word increasingly appearing in the mix in research (for example, here and here).

The word is also coming up as researchers are getting new tools to examine the interaction of tornadoes with their immediate surroundings. Microtopography looks like a potential factor in tornadic damage and in the tornadoes themselves, according to an AMS Annual Meeting presentation by Melissa Wagner (Arizona State Univ.) and Robert Doe (Univ. of Liverpool), who are working on this research with Aaron Johnson (National Weather Service) and Randy Cerveny (Arizona State Univ). Their findings relate tornado damage imagery to small changes in local topography thanks to the use of unmanned aerial systems (UASs).

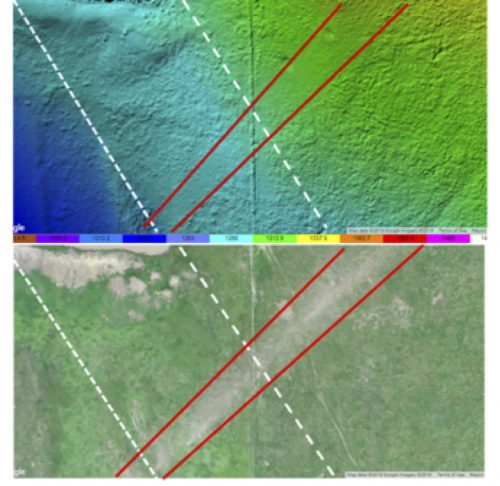

Microtopographic interactions of tornadic winds were captured in their UAS imagery. Here’s the 5-meter resolution RapidEye satellite imaging of a 30 April 2017 Canton, Texas, tornado path (panel a) versus higher-resolution UAS imaging:

The UAS surveys show that tornadic winds interact with sunken gullies, which appear as unscarred, green breaks (circled in red) in the track of browned damaged vegetation:

Erosion and scour are limited within the depressed surfaces of the gullies compared to either side. In another section of the track, track width increases with an elevation gain of approximately 74 feet, as shown in a digital elevation model and 2.5 cm resolution UAS imagery:

The advent of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) has opened new windows on tornado damage tracks. Decades ago, damage surveys took a big leap forward with airplane-based photography that provided a perspective difficult to achieve on the ground. Satellites also can provide a rapid overview but in relatively low resolution. UASs fly at 400 feet—and are still limited to line-of-sight control and the logistics of coordinating with local emergency and relief efforts, regulatory and legal limitations, not to mention still-improving battery technology.

However, UASs provide a stable, reliable aerial platform that benefits from high-resolution imaging and can discern features on the order of centimeters across. Wagner and colleagues were using three vehicles with a combined multispectral imaging capability that is especially useful in detecting changes in the health of vegetation. As a result their methods are being tested primarily in rural, often inaccessible areas of damage.

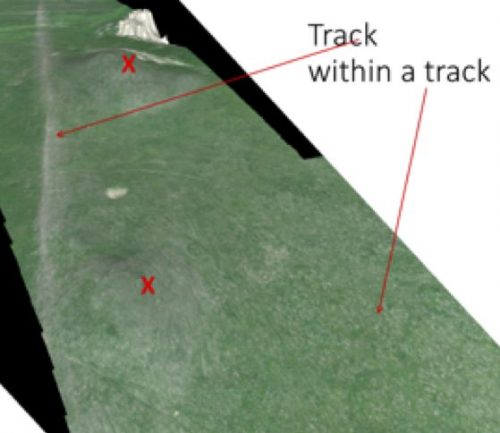

UAS technologies thus can capture evidence of multi-vortex tornadoes in undeveloped or otherwise remote, vegetated land. The image below shows a swath with enhanced surface scour over two hills (marked X). The arrow on the right identifies speckled white surface erosion, part of the main tornado wedge. Such imagery explains why, among other research purposes, Wagner and Doe are developing the use of UASs in defining tracks and refining intensity-scale estimates.

tornadoes

A Tale of Two Studies: Varied Perspectives at the AMS Meeting

by Maggie Christopher, Valparaiso University

On Sunday students presented nearly 200 posters of their research in grad school and summer internships. With so many topics covered, the session covered a variety of perspectives—often multiple perspectives on similar questions.

For example, two students from different universities did individual studies of the socioeconomic factors in fatalities due to tornadoes. But while Shadya Sanders from Howard University compared two case studies, Omar Gates, from the University of Michigan, set one tornado case in a climatological perspective.

Sanders compared the Joplin, Missouri, and Tuscaloosa, Alabama, tornadoes in 2011. Sanders looked at the differences in death rates for race, age, gender, and housing structures in each storm. She found, for example, a high rate of death amongst women, which she said is unusual compared to other data she looked at. Women generally will take the suggested protective action when warnings are issued.

Sanders also noticed that in Tuscaloosa people aged 21-30 died at a higher rate, probably because the University of Alabama is located in the city of Tuscaloosa. By contrast, in Joplin, more retail business were located in the path of the storm, rather than houses.

Similarly, Gates studied the effect of tornado outbreaks as climate changes. He hoped to show the risk of tornadoes striking cities. He focused his research on Oklahoma, and specifically the May 3, 1999 tornado in Moore. Gates used reanalysis data with the North American Regional Reanalysis (NARR), and also utilized 2010 Census Data, which included demographic information such as gender, race, age, and housing units.

Using ARCgis, Gates put together risk assessment maps for vorticity, moist static energy, and wind shear. These maps were then put together, along with the actual storm track, to locate the highest risk of tornadoes for that day.

Even with different approaches, Shayda and Gates had similar goals for their work. Shayda held focus groups in both cities to see what kinds of warnings citizens would find most helpful. She wants to insure that warnings get out to everyone, and she hopes to continue her research throughout the rest of the United States. Similarly, Gates hopes that continuing to look at the socioeconomic effects of tornadoes will lead to watches, outlooks, and warnings that are easier for people to decipher, saving lives.

New Standard Aims to Improve Tornado, Severe Wind Estimates

By Jim LaDue, NWS Warning Decision Training Branch

For more than four decades, the go-to for rating tornadoes has been the Fujita Scale, and in the last eight years, the Enhanced Fujita Scale, or EF Scale. Soon, scientists and NWS field teams will have a new and powerful benchmark by which to gauge the extreme winds in tornadoes and other severe wind events.

The American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) has approved the EF Scale Stakeholder Group’s proposal to develop a new standard for estimating wind speeds in tornadoes. This standard will allow, for the first time, a rigorous process to improve not only the EF-scale but to adopt new methods to assign wind speed ratings to tornadic and other wind events.

The intent is to standardize methods. According to the ASCE blog, “The content of the standard would include improvements to the existing damage-based EF scale to address known problems and limitations.” ASCE went on to state that the data used for estimating wind speeds would be archived.

The EF Scale Stakeholders Group, composed of meteorologists, wind and structural engineers, a plant biologist, and a hydrologist, held a series of meetings over the past year to discuss methods available to provide wind speed estimations. The consensus among the group is that many methods exist in addition to that used in the EF Scale today. These include mobile Doppler radar, tree-fall pattern analysis, structural forensics, and in situ measurements. The group also discussed ways that the EF Scale could be improved through the correction of current damage indicators and by adding new ones. The outcome of these discussions is available online.

The new standard will be housed under the Structural Engineering Institute (SEI) of the ASCE. Users of the standard include but are not limited to wind, structural, and forensic engineers, meteorologists, climatologists, forest biologists, risk analysts, emergency managers, building and infrastructure designers, and the media.

Interested parties are encouraged to apply to the committee, selecting Membership Category as either a General member with full voting privileges or as an Associate member with optional voting capabilities. Membership in ASCE is not required to serve on an ASCE Standards Committee.

The online application form to join the committee is available at http://www.asce.org/codes-standards/applicationform/.

The new committee will be chaired by Jim LaDue and cochaired by Marc Levitan of the National Institute of Standards and Technology. For more information or questions about joining the committee, please contact us at james . g . ladue @ noaa . gov and marc . levitan @ nist . gov.

Reassessing the Enhanced Fujita Tornado Scale

It’s been more than 40 years since Ted Fujita introduced his renowned Tornado Damage Scale – the Fujita Scale. And nearly a decade has passed since top tornado scientists first collaborated with structural engineers to create the Enhanced Fujita (EF) Scale for rating tornado winds more accurately based on advances in our understanding of the variety of damage they inflict. Now, an effort is underway to tweak the EF Scale further – and the National Weather Service is looking for input from AMS meeting attendees this week.

The effort stems from the observations and analysis of recent violent tornado events: the massive tornado outbreak across the South in April 2011; the violent (EF5) Joplin, Missouri tornado of May 2011; and the Newcastle-Moore, Oklahoma EF5 tornado of May 2013. Survey teams were able to use more than two dozen “damage indicators,” such as wood-frame homes, strip malls, and schools—each further categorized by multiple “degrees of damage”—to gauge tornadic winds. But questions and even discrepancies arose among the survey teams as they scoured the wreckage of entire neighborhoods.

Oral and poster presentations throughout this week at the AMS Annual Meeting in Atlanta share information about the damage surveys, findings from reports such as the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) technical investigation of the Joplin tornado and FEMA’s Mitigation Assessment Team Report on the Spring 2011 tornadoes, as well as thoughts for improving the EF-scale:

- The Joplin Tornado: Lessons Learned from the NIST Investigation (Tuesday, 9:15 a.m., Georgia Ballroom 2)

- Damage Survey and Analysis of the 20 May 2013 Newcastle-Moore, OK, EF-5 Tornado (Poster 828, Wednesday, 2:30-4 p.m., Hall C3)

- Aerial Damage Survey Analysis of the 20 May 2013 Moore Tornado (Poster 829, Wednesday, 2:30-4 p.m., Hall C3)

- Side-by-side tree and house damage in the May 2013 Moore, OK EF-5 tornado: Lessons for the Enhanced Fujita scale (Poster 831, Wednesday, 2:30-4 p.m., Hall C3)

- A related poster presentation looks at assigning EF-scale ratings to tree damage in severely damaged forests using only aerial photos.

- Photogrammetric analysis, from the ground and the air, was also used to survey the huge El Reno, Oklahoma of May 31, 2013,

- Terminal Doppler Weather Radar (TDWR) in Oklahoma City captured rare up-close velocity data of the Newcastle-Moore tornado that can be compared with survey estimates of tornado damage and intensity rankings.

All of these represent on-going thinking about the EF Scale and how to refine it.

If you’d like to get involved, NWS is hosting an open discussion of the EF Scale to acquire feedback on its strengths and deficiencies. Space is limited so sign up today.

The Moore Tornado from Above

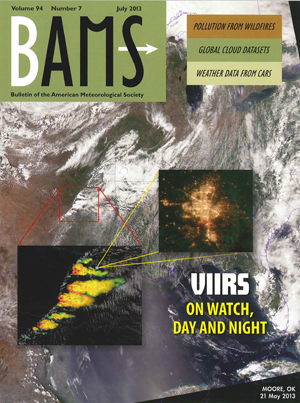

The July issue of BAMS includes a feature on the new and improved imaging capabilities of the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS), one of the five instruments aboard the Suomi NPP satellite. The cover montage highlights VIIRS’s expanded spectral aptitude and microscale resolution by depicting  three different perspectives on the tornado outbreak that swept across the Midwest on May 20, culminating in detailed nighttime evidence of the track of devastation in Moore, Oklahoma, as detected on May 21.

three different perspectives on the tornado outbreak that swept across the Midwest on May 20, culminating in detailed nighttime evidence of the track of devastation in Moore, Oklahoma, as detected on May 21.

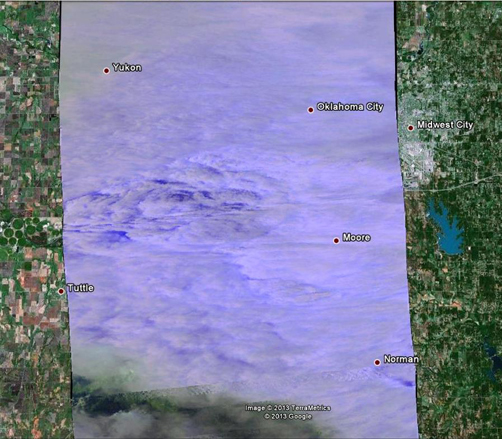

That month, the instruments on Suomi NPP were being calibrated by aircraft that in many cases flew directly under the path of the satellite. On May 20, one of these planes–an ER-2 flying above the cloud cover at approximately 65,000 feet–used the MODIS/ASTER Airborne Simulator (MASTER) to capture images of the storm that brought the EF5 tornado to Moore. The image below shows the tornado system minutes before it reached the city, and is overlaid on a Google Earth map to show the tornado location.

Twister that Killed 4 Storm Chasers Widest Ever

The tornado that killed 18 people in and around El Reno, Oklahoma on Friday, including three professional tornado researchers and an amateur storm chaser, was a record 2.6 miles wide, according to the National Weather Service (NWS).

(Source: NWS Forecast Office, Norman, Oklahoma)

The NWS in Norman, Oklahoma posted the image above to its Facebook page Tuesday. In addition to being the widest tornado in U.S. history, the El Reno tornado was also rated an EF-5 with winds “well over 200 mph,” the Norman NWS stated on Facebook.

According to a blog post by Jason Samenow of the Washington Post’s Capital Weather Gang, the previous record width of a tornado was 2.5 miles, belonging to the Wilber-Hallam, Nebraska twister of May 22, 2004. It was rated EF-4 in Hallam, south of Lincoln, and damaged or destroyed about 95 percent of the village of 200 people, killing one person and injuring 37.

Friday’s tornado in El Reno, a small city just west of Oklahoma City, was upgraded to an EF-5 on the 0-5 Enhanced Fujita Scale not because of its size but because of radar-measured winds in its enormous vortex of nearly 300 mph.

According to Samenow’s post, radar teams headed by renowned tornado researchers Howard Bluestein of the University of Oklahoma and Josh Wurman of the Center for Severe Weather Research were near the El Reno tornado gathering data. Bluestein said two of his graduate students measured winds of 296 mph in the tornado’s funnel, while Wurman’s team observed winds of 246-258 mph. Both teams were scanning the tornado with mobile Doppler radars, but from different locations.

The violent and deadly El Reno tornado occurred less than two weeks and a mere 20 miles from the EF-5 tornado that devastated Moore, Oklahoma on May 20. Two dozen people lost their lives in that tornado. It brought hard luck and hard lessons back to Moore, crossing the path of the infamous EF-5 tornado of May 3, 1999. Wurman’s Doppler on Wheels radar clocked winds in the 1999 Moore tornado at over 300 mph.

Over the weekend, numerous media outlets (KFOR-TV, CNN, The Weather Channel), cable TV channel websites (NatGeo, The Discovery Channel), and blog posts (Capital Weather Gang, Weatherunderground) covered the shocking news of the first-ever deaths of storm chasers by a tornado. Tim Samaras, a professional storm chaser and tornado researcher for nearly 30 years and an Associate Member of the AMS, along with his photographer son Paul and researcher Carl Young were killed when their chase vehicle was violently thrown and mangled by the El Reno tornado. The Daily Oklahoman reported Tuesday that amateur storm chaser Richard Charles Henderson was killed the same way. His pickup truck was overrun by the tornado winds moments after he sent a friend a cellphone photo of the El Reno tornado.

Hard Luck, Hard Lessons in Moore

While we hope, pray, and provide for survivors of Monday’s tragedy in Moore, Oklahoma, it is impossible to ignore the terrible turn of bad luck this tornado represents.

In 1999 Moore was struck by what has been considered the most powerful tornado ever observed on radar–winds over 300 miles an hour aloft. That was a billion dollar disaster that claimed 36 lives. Then, in 2003, the same path of destruction was crossed again–fortunately claiming no lives. Nonetheless at the time this powerful twister was rated an F-4 on the old version of the Fujita scale. And this week…unspeakable destruction and loss of loved ones as a mile-wide-plus tornado—an EF-5 on the Enhanced Fujita scale—yet again crossed the benighted path through Moore.

People in tornado country are vulnerable. It should be as simple as that. But the people of Moore are being tested beyond any threshold of resilience we might expect from the odds.

Clearly, lightning can strike in the same place twice. The people of Moore, and of Oklahoma in general, understood that, and have been open to the advice of the weather and climate community. For example, in 2002 the greater Oklahoma City metropolis spent $4.5 million to upgrade and expand its warning siren system. The Moore area alone has a network of 36 sirens and apparently took full advantage of the 16 minute warning lead time. Furthermore, areport from Oklahoma Climate Survey’s Andrea Dawn Melvin revealed the terrible vulnerability of schools in the 1999 disaster (she presented these findings at the 2002 AMS Annual Meeting; and at the symposium for the one-year anniversary of the tornado, in Norman). In response, school districts in the state have taken her advice to heart, revising emergency plans, and in some case building or reinforcing shelters.

But making good luck out of bad is an unceasing, and apparently unforgiving task, for meteorologists and citizens alike. Preparations are rarely perfect. Even though Melvin’s report helped spur Oklahoma City and other jurisdictions to create safe rooms in schools, other cities, like Moore, did not go this far in safety preparations. The two schools damaged in 1999 were rebuilt with safe rooms, but the other schools in the district–including those destroyed on Monday–were not upgraded in this manner.

Furthermore, while the 1999 tornado was among the most thoroughly analyzed of all severe storms in history, lessons drawn about building safety were not always heeded. A Weather and Forecasting paper by engineer and storm chaser Tim Marshall showed how the damage from the 1999 Moore tornado looked like the work of extreme winds until you examined how the houses had been built. Connections between frame and foundation, roof and walls had been compromised easily because of poor construction practices. Garage doors had been uncommonly weak points, forcing otherwise fine houses to yield to the storm. Marshall concluded, “Houses with F4 or F5 damage likely failed when wind gusts reached F2 on the original F scale.”

And yet, inspecting the rebuilding in Moore 40 days after the disaster, Marshall already found numerous instances of the same construction mistakes being repeated. It was rare for builders to exceed code standards in order to strengthen houses for a repeat tornado.

Unfortunately nature did repeat. While construction improvements would not prevent failure of a house in the worst case scenario, there are a lot of tornadoes in which safety can be improved by using the right kinds of fasteners, improving shelters, updating sirens, and the like. Monday’s disaster goes far beyond the placement of hardware and planks, but that is not the point. These tornadoes are a reminder that all this happened before and can happen again.

Pray that hard luck finally ends for Moore, but remember that we are a community that must keep on learning hard lessons.

Cool Weather Contributing to Historically Low Tornado Count

The lack of tornadoes in the United States from May of 2012 to April of this year has been “remarkable,” according to Harold Brooks of NOAA’s Severe Storms Laboratory. In that time, there have been an estimated 197 tornadoes rated EF1 or stronger (exact totals are available through January; estimates for February through April won’t be confirmed until July). That is 50 fewer tornadoes than the previous low for a 12-month period (not including overlapping periods, such as April 2012-March 2013), established from June 1991 through May 1992. (Reliable data go back to 1954.)

The even better news is that there have been only seven fatalities from tornadoes in the last year, which according to Tom Grazulis of the Tornado Project is the second-fewest on record, and his reliable records date back to 1875. The only yearlong period (again, not including overlapping periods) with fewer fatalities was September 1899-August 1900, with 5.

According to AccuWeather’s Alex Sosnowski, the dearth of twisters may be attributed to a pattern of dry, cold air east of the Rockies, which has affected the formation of thunderstorms in Tornado Alley. According to Sosnowski,

The wedge of cool air forces the base of the clouds from the thunderstorms to be higher off the ground.

This setup limits not only the number of tornadoes but also damaging wind gusts, since most of the action is occurring several thousand feet above the ground. The pattern can still produce a number of storms with hail.

Additionally, the jet stream has been farther south than normal, stifling the movement of warm, moist air from the Gulf of Mexico to the southern United States. If this large southward dip in the jet stream continues through the spring and into the beginning of summer, severe storms will be inhibited even as seasonal temperatures finally begin to arrive.

Investigating Tornado Fatalities

Men, particularly the elderly, die at a disproportionately higher rate than other population groups. It’s a well-known fact to those studying tornado fatalities, but what researchers are trying to find is a way to keep more of these high risk men responsive to alerts and therefore save lives.

Wednesday morning at the AMS Annual Meeting, several researchers discussed their research on tornado fatalities. The policy session, chaired by Kimberly E. Klockow of the University of Oklahoma, showed that social sciences and data collection methods are improving the way we can analyze deadly storms and adequately warn the public before these storms strike.

Amber Cannon of the University of Oklahoma started the discussion with a comparison of data from tornado outbreaks in Alabama on 3 April 1974 and 27 April 2011. She noted that, although more people died in the 2011 outbreaks than in 1974, the population density had increased during that time. As a result, the fatality rates very similar.

If the death rate isn’t going up, then maybe we can bring it down. Shadya Sanders, from Howard University, presented her research regarding the super outbreak of tornadoes in 2011. She found that, while a 45% tornado risk seems huge to a meteorologist, the average person may not see the gravity of such a situation. Her work with focus groups has shown the importance of education for children and risk awareness for adults.

Soon, according to Hope-Anne Weldon of the University of Oklahoma, there will be a “one-stop shop” for killer tornado information from the NOAA/NWS Storm Prediction Center. Weldon spent an entire summer filling in gaps in data about tornado victims, clarifying tags of age, gender, and domicile in statistics for 1991-2010–in all 400 tornadoes killing more than 1,100 people. With more detailed data, she noted, social scientists will be able to draw even better conclusions.

New Warnings, New Words

National Weather Service offices in Missouri and Kansas recently initiated an experiment testing new tornado warnings that combine more specific information with more descriptive language than have been used in the past to describe the potential effects of storms. The experiment is called “Impact Based Warning,” and is meant to bluntly tell residents in the path of tornadoes what could result if they don’t seek shelter. By using phrases such as “complete destruction” and “unsurvivable if shelter not sought below ground,” the NWS is hoping to “better convey the threat and elevate the warning over a more typical warning,” according to Dan Hawblitzel of the Pleasant Hill, Missouri NWS office.

The new alerts got their first big test last weekend when more than 100 twisters were reported in Kansas, Oklahoma, Nebraska, and Iowa. While the NWS’s Storm Prediction Center issued a warning of possible life-threatening storms in several midwestern states days before they touched down, in Kansas the words used in the new alerts were particularly trenchant: “You could be killed if not underground or in a tornado shelter. Many well-built homes and businesses will be completely swept from their foundations.” And the warnings seem to have worked. Despite the large number of storms, only six people were killed—all in an overnight tornado that hit Woodward, Oklahoma. In Wichita, Kansas, a twister tore through a mobile-home park during nighttime hours, but there were no fatalities.

The Impact Based Warning experiment was developed by the NWS in consultation with social scientists. Along with the new vernacular, it includes some key additions to regular tornado warnings, including information that identifies the hazard (hail, winds, tornado, etc.), indicates whether the hazard has been spotted by radar or by people on the ground, and describes potential effects of the hazard (loss of life, damage to trees or buildings, etc.). The warnings can be used not only for tornadoes, but also to signify life- or property-threatening thunderstorms. The experiment is scheduled to run through the end of November, at which point it will be evaluated and considered for more widespread use.

The initiative comes  just one year after tornadoes killed more than 500 people in the United States—the deadliest season in almost 60 years. The 2011 year in tornadoes is examined in the new AMS book, Deadly Season: Analysis of the 2011 Tornado Outbreaks, by Kevin M. Simmons and Daniel Sutter. The book is a follow-up to the authors’ Economic and Societal Impacts of Tornadoes, published by AMS in 2011. The new title looks at possible factors contributing to the outcomes of 2011 tornado outbreaks, including assessments of Doppler radar, storm warning systems. and early recovery efforts. Both books can be purchased here.

just one year after tornadoes killed more than 500 people in the United States—the deadliest season in almost 60 years. The 2011 year in tornadoes is examined in the new AMS book, Deadly Season: Analysis of the 2011 Tornado Outbreaks, by Kevin M. Simmons and Daniel Sutter. The book is a follow-up to the authors’ Economic and Societal Impacts of Tornadoes, published by AMS in 2011. The new title looks at possible factors contributing to the outcomes of 2011 tornado outbreaks, including assessments of Doppler radar, storm warning systems. and early recovery efforts. Both books can be purchased here.