As society urbanizes, weather impacts are exacerbated in sometimes-unfamiliar ways. Case in point: the snow, ice, and cold that paralyzed much of the southeastern United States this week. More specifically–and more germane to AMS members attending this year’s AMS Annual Meeting–delays caused by gridlock in Atlanta were being measured in days, not hours, and thousands of people were stranded in schools, stores, their cars, and other places that weren’t their homes.

The timing of this unfortunate event is appropriate, given the Annual Meeting’s theme of “Extreme Weather–Climate and the Built Environment: New Perspectives, Opportunities, and Tools.” Even before this week’s events, the meeting was going to be buzzing with discussions about all aspects of weather and climate impacts in urban areas. In the wake of events of this week, that buzz may turn into a roar.

One topic certain to elicit a storm of interest is road transportation–the most visible of the vital, weather-prone infrastructure systems in any urban area. At the Ninth Symposium on Policy and Socio-Economic Research, a session on Wednesday (4:00-5:30 PM, Room C107) titled “Observing Weather and Environment along the Nation’s Transportation Corridors” will feature a look at weather-observation sensors for cars, which offer “the potential of turning vehicles into moving weather stations to fill road weather observation gaps.” An equally salient presentation in that session will explore best practices for getting timely and accurate weather and climate information to transportation decision makers.

The 30th Conference on Environmental Information Processing Technologies will include a session on “Road Weather Applications” (Monday, 1:30-2:30 PM, Room C105). One talk will explore the Maintenance Decision Support System, which “blends existing road and weather data sources with numerical weather and road condition models in order to provide information on the diagnostic and prognostic state of the atmosphere and roadway.” Another presentation will analyze driver awareness during two 2013 winter storms in Utah to examine ways to improve communication of hazard information to the public.

The Second Symposium on Building a Weather-Ready Nation will have a session on “Innovative Partnerships in Public Outreach and Decision Support Services” (Tuesday, 3:30-5:30 PM, Georgia Ballroom 2). Included in that session will be an exploration of how the NWS and Federal Highway Administration are collaborating to improve communication and data sharing before, during, and after weather events that have a significant impact on transportation, public behavior, and emergency response. Another talk will take a broader view by examining ways to enhance nationwide environmental education and create a more weather-ready nation–a goal that this week’s events make clear remains of vital import.

surface transportation

Intelligent Transportation Systems: A Drive-By Opportunity

A market research report released this month predicts that vehicle fleet management solutions, involving both software and hardware, will balloon from a $10 billion to a $30 billion industry within five years. The Dallas-based company Markets and Markets cites not only growing numbers of planes, trucks, cars, and ships, especially in Asia, but also several trends that tap the expertise of atmospheric scientists: “The environmental concerns, CO2 emission reduction norms, and fleet operators’ need for operational efficiencies are expected to serve as major drivers for the fleet management market.”

The report echoes the message of another report issued just a month ago by the market research firm, Technavio, which touted double-digit growth in the global intelligent transportation systems markets through 2016.

This can only be good news for a weather community that is already essential to fleet management in the aviation and maritime industries, right? Well, maybe. Especially in the area of smart surface transportation, the opportunities are huge, but everything depends on yet-to-be specified, rapidly evolving markets and technologies. This is a formative moment in that market–a drive-by opportunity. The chance to embed meteorological priorities in this burgeoning field–specifically, equipping vehicles to report key environmental variables to the meteorological community–may pass by quickly. Hence, several years ago an AMS Annual Partnership Committee on Mobile Observations was asked to “articulate a clear vision for mobile data that captures the immense opportunities for these data to improve surface transportation weather services.”

The resulting report is available on the web (here). However, in case you don’t have time to read all 88 pages there, or if you missed the multiple sessions on transportation at this week’s AMS Summer Community Meeting, you have another option. Read the shorter version of the report, by William Mahoney and James O’Sullivan, in the July issue of BAMS.

The article, “Realizing the Potential of Vehicle-Based Observations,” stresses that the involvement of meteorology in intelligent vehicle systems is not a given—our community has to be engaged in the broader technological efforts that are already underway.

Whether this opportunity is acted upon or missed (at least initially) will depend greatly on the weather community’s technical understanding and eventual adoption of … unique datasets and their level of participation in connected vehicle initiatives within the transportation community.

The stakes are obvious, both in getting real-time weather information to drivers and in getting that data into the hands of the atmospheric science community. More than 7,000 people are killed, and more than 600,000 are injured, annually in weather related accidents on the road. Meanwhile,

the availability of hundreds of millions of direct and derived surface observations based on vehicle data will have a significant impact on the weather and climate enterprise. The potential improvements in weather analysis, prediction, and hazard identification should have a large positive effect on all weather-sensitive components of the U.S. economy and the capability to sense the lower atmosphere at finer scales than traditional observation systems, which will improve the detection and diagnosis of extreme weather events that affect lives and property.

It’s no accident, then, that meteorologists are eyeing your car as the observing platform for this future transformation. Mahoney and O’Sullivan detail some of the possibilities:

Vehicle-based air temperature observations could provide additional temporal and spatial specificity required to more clearly identify rain/snow boundaries; also, antilock brake and vehicle stability control event data could support the diagnosis of slippery pavement conditions. Even the most common components of the vehicle can begin to tell a story about the near-surface atmospheric and pavement conditions through the intelligent utilization of vehicle data elements, such as windshield wiper state, external air temperature, headlamps, atmospheric pressure, sun sensors, vehicle stability control, and the status of an antilock breaking system.

For all the benefits of vehicle-based observing networks, however, there are significant challenges. For example, Mahoney and O’Sullivan note, “Traditionally, near-surface weather observations have been generated by stationary platforms. Taking observations from mobile platforms, particularly passenger and fleet vehicles, introduces new dimensions of complexity.” In addition, among other obstacles:

Many of the normal concerns associated with dedicated weather sensors—siting, maintenance, and calibration—are exacerbated with mobile sensors, especially when large numbers are to be sited on a wide variety of vehicles driven by people with varying interest in those sensors. The best place to site a temperature sensor on a particular model of car may not be the best location for a pressure sensor, and the best place for a particular sensor on one model of car might not even exist on another model.

Beyond the hopes of placing dedicated weather sensors on cars, there are, of course, existing engine sensors and weather-related vehicle behavioral data:

This type of information could be made available quickly without deployment of new sensors, it is considered to be the “low-hanging fruit” of mobile weather sensing. However, it presents some very challenging calibration issues and may ultimately not provide consistent enough information for weather applications.

There are also communications challenges: one intelligent transportation solution that is gaining traction involves direct, dedicated short-range vehicle-to-vehicle communications links between cars sharing the road. The weather community, by contrast, will require longer-range communications solutions to gather information from vehicles; somehow short-range, on-the-road links will need to be integrated with other options such as existing cellular networks creates new challenges .

Meanwhile, there are not just technical but also fiscal and institutional—perhaps legal and regulatory—barriers to successful implementation of the roadway network goals. The report emphasizes that there are solutions to these barriers, even though “a litany of barriers…may leave … the impression that mobile weather observing is too difficult, too costly, or otherwise too problematic to achieve on any useful scale.”

The institutional barriers make plain why improving forecast services for transportation was a vital one for consideration during the high-level considerations at the AMS Summer Community meeting, and by all of us in the weather and climate community. Mahoney and O’Sullivan show that the challenge of emerging roadway systems is an opportunity to shape development of the weather community and how it works:

Management of highways and the traffic they carry involves a large number of active participants, including the federal government, states, counties, municipalities, and regional authorities. In addition, the immature nature of road weather management offers numerous opportunities for entrepreneurial innovation, opening the door for commercial entities with potentially unconventional approaches to deploying mobile weather sensors and managing and exploiting the data from those sensors. At this point, it is not clear that, with all the various participants with their differing needs and agendas, the mobile weather observing enterprise is manageable in the normal sense of the word. In any case, there is no overall authoritative vision for the deployment, operation, management, and governance of mobile weather observing capability, let alone a high-level strategy, concept of operations, or implementation plan.

The Hazards of the Winter Roads

- 17% of all fatal accidents and 7,130 persons are killed in weather-related accidents each year.

- The Midwest has the greatest average intra-annual variability for both trucks and passenger vehicles. For large commercial trucks, the average monthly peak occurs in January with 38.29% of accidents occurring with adverse-weather, and a minimum in June of 8.27%. For passenger vehicles, accidents are less affected by adverse-weather with an average intra-annual peak of 30.28% in January and a minimum of 6.32% in June.

- The South has the least average intra-annual variability of accidents in adverse-weather.

- Adverse-road related accidents are greater in all regions than adverse-weather due to the fact that accidents can occur on wet or snow/ice covered roads in the absence of adverse-weather.

Commutageddon, Again and Again

Time and again this winter, blizzards and other snow and ice storms have trapped motorists on city streets and state highways, touching off firestorms of griping and finger pointing at local officials. Most recently, hundreds of motorists became stranded on Chicago’s Lake Shore Drive as 70 mph gusts buried vehicles during Monday’s mammoth Midwest snowstorm. Last week, commuters in the nation’s capital became victims of icy gridlock as an epic thump of snow landed on the Mid Atlantic states. And two weeks before, residents and travelers in northern Georgia abandoned their snowbound vehicles on the interstate loops around Atlanta, securing their shutdown for days until the snow and ice melted.

Before each of these crippling events, and historically many others, meteorologists, local and state law enforcement, the media, and city and state officials routinely cautioned and then warned drivers, even pleading with them, to avoid travel. Yet people continue to miss, misunderstand, or simply ignore the message for potentially dangerous winter storms to stay off the roads.

Obviously such messages can be more effective. While one might envision an intelligent transportation system warning drivers in real time when weather might create unbearable traffic conditions, such services are in their infancy, despite the proliferation of mobile GPS devices that include traffic updates. Not surprisingly, the 2011 AMS Annual Meeting in January on “Communicating Weather and Climate” offered a lot of findings about generating effective warnings. One presentation in particular—”The essentials of a weather warning message: what, where, when, and intensity”—focused directly on the issues raised by the recent snow snafu’s. In it, author Joel Curtis of the NWS in Juneau, Alaska, explains that in addition to the basic what, where, and when information, a warning must convey intensity to guide the level of response from the receiver.

Key to learning how to create and disseminate clear and concise warnings is understanding why useful information sometimes seems to fall on deaf ears. Studies such as the Hayden and Morss presentation “Storm surge and “certain death”: Interviews with Texas coastal residents following Hurricane Ike” and Renee Lertzman’s “Uncertain futures, anxious futures: psychological dimensions of how we talk about the weather” are moving the science of meteorological communication forward by figuring out how and why people are using the information they receive.

Post-event evaluation remains critical to improving not only dissemination but also the effectiveness of warnings and statements. In a blog post last week following D.C.’s drubbing of snow, Jason Samenow of the Washington Post’s Capital Weather Gang (CWG) wondered whether his team of forecasters, and its round-the-clock trumpeting of the epic event, along with the bevy of weather voices across the capital region could have done more to better warn people of the quick-hitting nightmare snowstorm now known as “Commutageddon.” He concluded that, other than smoothing over the sometimes uneven voice of local media even when there’s a clear signal for a disruptive storm, there needs to be a wider effort to get the word out about potential “weather emergencies, or emergencies of any type.” He sees technology advances that promote such social networking sites as Twitter and Facebook as new ways to “blast the message.”

Even with rapidly expanding technology, however, it’s important to recognize that simply offering information comes with the huge responsibility of making sure it’s available when the demand is greatest. As CWG reported recently in its blog post “Weather Service website falters at critical time,” the NWS learned the hard way this week the pitfalls of offering too much information. As the Midwest snowstorm was ramping up, the “unprecedented demand” of 15-20 million hits an hour on NWS websites led to pages loading sluggishly or not at all. According to NWS spokesman Curtis Carey: “The traffic was beyond the capacity we have in place. [It even] exceeded the week of Snowmageddon,” when there were two billion page views on a network that typically sees just 70 million page views a day.

So virtual gridlock now accompanies road gridlock? The communications challenges of a deep snow continue to accumulate…

On the Road Again!

by William Hooke, AMS Policy Program Director. From the AMS project, Living on the Real World

The meetings and discussions will be of interest in and of themselves. In some areas of our lives, weather is vital, but we can do little more than sigh. Give a

farmer thirty minutes notice of a coming hailstorm? He’s going to lose his wheat crop anyway; he can just start the grieving process half an hour sooner. In other venues, we’ve got plenty of weather information, but we’ve made it less relevant. That’s why offices are housed in buildings… and why we have domed football stadiums.

But roadways are an intersection (forgive me…too tempting!) where (1) weather affects safety and the economy, and where (2) those affected – the drivers, the traffic managers, the roadway maintenance folks, the businesses dependent on supply lines fed by road – if given the right information in the right way, can actually do something about it. A hailstorm is coming? Traffic managers can put out the word; drivers in the hailstorm’s path can divert or stand down until the hazard passes. Snow is on the way? We can get out the trucks with the plows and salt. And people are using the roadways to get from home to the office, or to that football game, aren’t they? Even in this age of virtual connectivity, physical connection still matters, commercially and socially, and much of that connection is made by roadway.

So road weather is a very special topic, rich with potential for improving the human condition.

We also find road weather to be an interesting example – a microcosm, if you will – of policy issues that play across what appears at first blush to be a “stovepiped” landscape. But let’s probe a little deeper. In this instance, we find leaders who see their institutions as the organ pipes they are, and are jamming, playing a little music together (to build on yesterday’s metaphor from my post, “Stovepipes! The Musical“). They’re effectively working across boundaries – boundaries separating::

Federal agencies. The DoC/NOAA/National Weather Service and the DoT/Federal Highway Administration each have a piece of the puzzle, don’t they? To be valuable, weather information must be applied. As the FHWA tries to make road travel and commerce safer and more efficient, it must integrate weather with traffic conditions, road maintenance, and other elements of the mix. To be useful, the agencies need each other! At the policy forum, they’ll be signing an memorandum of understanding (MOU) – a policy document – committing to another five years’ collaboration on road weather research and services.

And by the way, there are policy interfaces within each of those two Cabinet-level Departments, aren’t there? FHWA is competing with its rather larger sister agency, the Federal Aviation Administration, the Federal Railroad Administration, the Maritime Administration (MARAD), and many more, for attention at the top. NWS is always trying to make sure

The Road to Safer Driving Is Paved with Meteorology

Storm chasing is sometimes as much a gripping challenge of driving through nasty weather as it is a calculated pursuit of meteorological bounties.

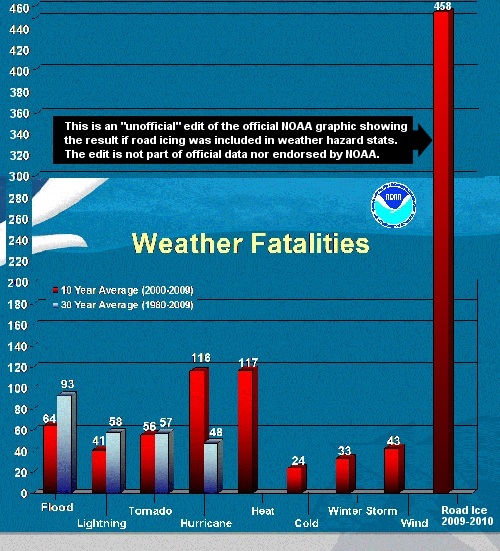

So perhaps it’s not so surprising that it took a storm chaser…Dan Robinson’s his name…to start a web site about the fatal hazard of ice and snow on our roads. Over half of the weather-related deaths on American roads each year are in wintry conditions.

Robinson took the liberty of tacking road statistics into the preliminary NOAA numbers for weather hazards (recently released for 2009 here).

The effect is striking, indeed, and a good lead in to Bill Hooke’s report from a Federal Highway Administration workshop today on road weather and the future of intelligent transportation systems.

Clearly we’ve got a lot of work to do and a lot of lives to save…Hooke, the AMS Policy Program Director, makes the case and points out some of the bumps in the road to better weather safety in your car.

Making a MoPED with Big Rigs

Speaking of the future of weather information along transportation corridors, one of the presenters in the Weather and Transportation sessions Monday (1:30 p.m.) is Brian Bell of Global Science & Technology, an exhibitor at the upcoming Annual Meeting. His topic is a project that will show NOAA how well the commercial trucking fleet can serve as an automated system to gather and report weather information on the road, just as airliners do in the air.

Last year at the AMS meeting GS&T demonstrated a novel mobile weather station with an inflatable satellite dish for easy deployment. But this fall the West Virginia company won the 9-month contract from NOAA to build the Mobile Platform Environmental Data observation network (MoPED). To learn more about the project before the Annual Meeting, see this article from the Times West Virginian.

Are Smarter, Safer Roads Good for Us?

It’s not often you hear that congested traffic arteries are good for you. But this is what you find in a thought-provoking recent Op-Ed in the Wall Street Journal on managing traffic problems in an environmentally sustainable way:

Congestion isn’t an environmental problem; it’s a driving problem. If reducing it merely makes life easier for those who drive, then the improved traffic flow can actually increase the environmental damage done by cars, by raising overall traffic volume, encouraging sprawl and long car commutes. A popular effort to curb rush-hour congestion, freeway entrance ramp meters, is commonly seen as good for the environment. But they significantly decrease peak-period travel times—by 10% in Atlanta and 22% in Houston, according to studies in those cities—and lead to increases in overall vehicle volume. In Minnesota, ramp metering increased overall traffic volume by 9% and peak volume by 14%. The increase in traffic volume was accompanied by a corresponding increase in fuel consumption of 5.5 million gallons.

The author, David Owen, goes on to recommend solutions—part pricing and part planned scarcity—to maintain congestion while raising funds and demand for more sustainable urban transportation systems.

This counter-intuitive argument sets a good context for the Interactive Information and Processing Systems conference at the AMS Annual Meeting in Atlanta. Much of Monday’s agenda for IIPS (and other conferences) focuses on the coming age of intelligent transportation—intelligent cars, roadways, and drivers based in part on ingenious means of collecting and using high resolution weather data. You’ll want to get a glimpse of this safer and more efficient future in Paul Pisano’s report on the “Clarus Regional Demonstration” project and other talks Monday starting at 11 a.m.

Because the presentations in Atlanta focus on engineering systems for more roadway efficiency, it would be disconcerting to think of them as contributing to the environmental morass rather than helping to solve it. But that would be an oversimplification of Owen’s essay as well as market-based solution in general. Don’t economists generally tell us that uninhibited flow of information helps balance markets? Better weather information may be the essence of economical solutions to the environmental dilemmas of roadway planning and use.

The talk that addresses congestion from a weather perspective most directly will be Monday afternoon. Ralph Patterson of Utah’s Department of Transportation will discuss results from a study of vehicle speed, spacing, and other factors in winter traffic last year. He also adds in psychological dimensions, looking at the way drivers respond to various forms of weather information. The fast growing state is looking for ways to decrease the $250 million annual costs of traffic congestion. This session should give us a glimpse at the myriad ways meteorologists can help improve an international urban quandary.