The AMS 2024 Presidential Panel Session “Transition to Carbon-Free Energy Generation” discusses crucial challenges to the Energy Enterprise’s transition to renewables, and the AMS community’s role in solving them. Working in the carbon-free energy sector on research and development including forecasting and resource assessment, grid integration, and weather and climate effects on generation and demand, the session’s organizers know what it’s like to be on the frontlines of climate solutions. We spoke with all four of them–NSF NCAR’s Jared A. Lee, John Zack of MESO, Inc., and Nick P. Bassill and Jeff Freedman of the University at Albany–about what to expect, and how the session ties into the 104th Annual Meeting’s key theme of “Living in a Changing Environment.” Join us for this session Thursday, 1 February at 10:45 a.m. Eastern!

What was the impetus for organizing this session?

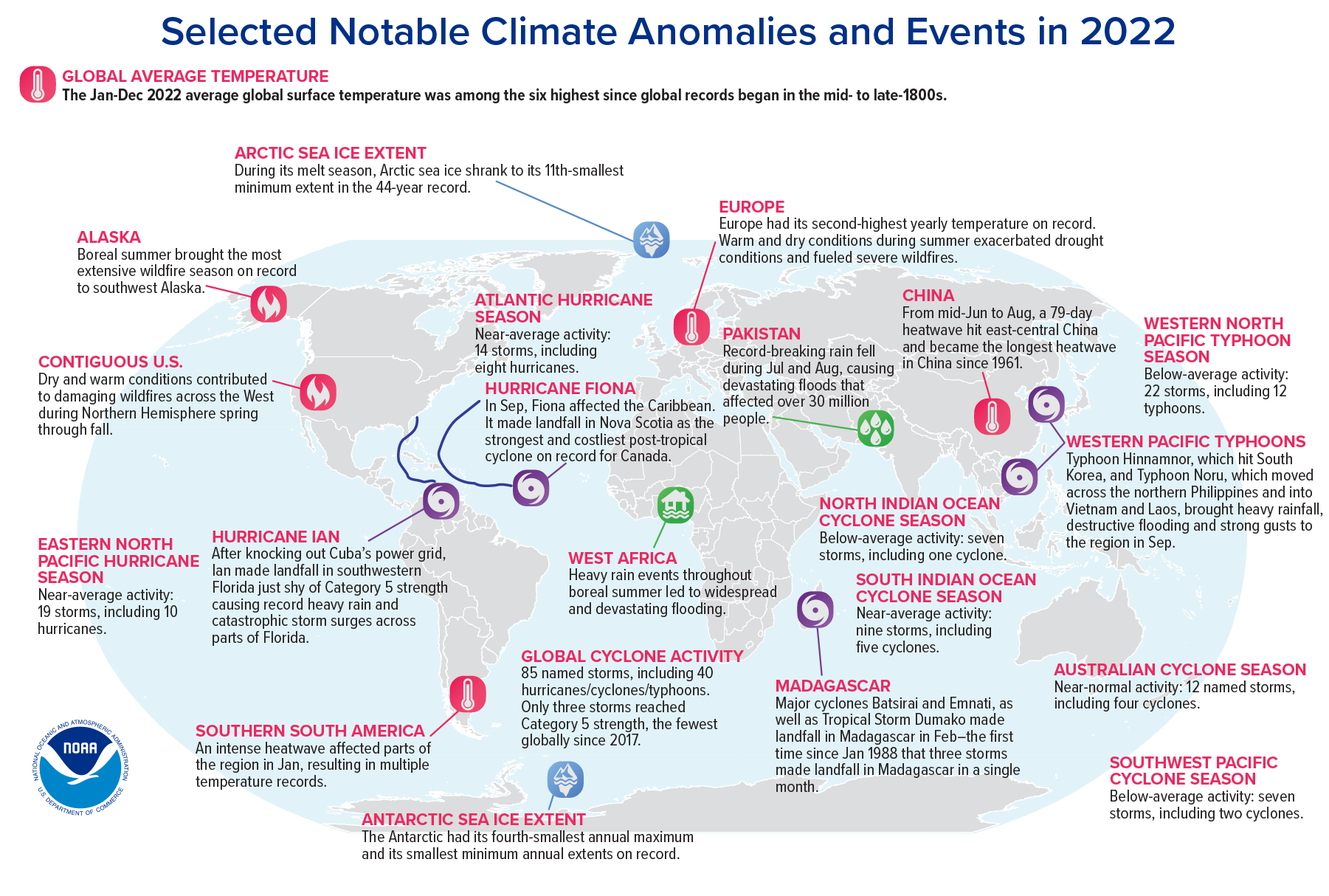

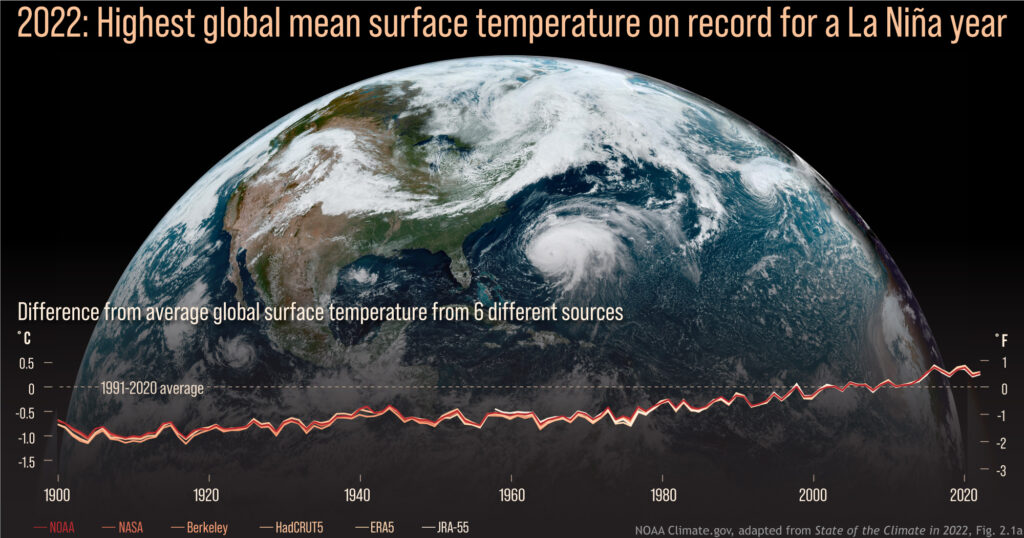

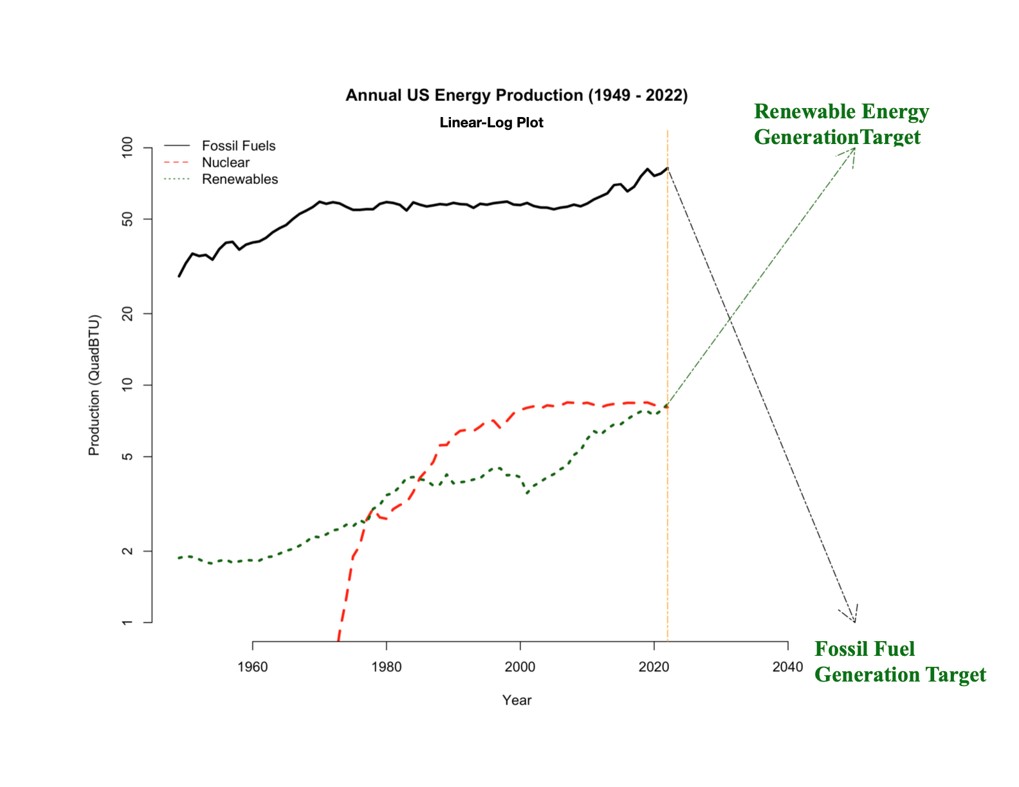

Jared: With the theme of the 2024 AMS Annual Meeting being, “Living in a Changing Environment,” it is wonderfully appropriate to have a discussion about our in-progress transition to carbon-free energy generation, as a key component to dramatically reduce the pace of climate change. But instead of merely having this be yet another forum in which we lay out the critical need for the energy transition, we organized this session with these panelists (Debbie Lew, Justin Sharp, Alexander “Sandy” MacDonald, and Aidan Tuohy) to shine a light on some real issues, hurdles, and barriers that must be overcome before we can start adding carbon-free energy generation at the pace that would be needed to meet aggressive clean-energy goals that many governments have by 2040 or 2050. The more that the weather–water–climate community is aware of these complex issues, the more we as a community can collectively focus on developing practical, innovative, and achievable solutions to them, both in science/technology and in policy/regulations.

Jeff: We are at an inflection point in terms of the growth of renewable energy generation, with hundreds of billions of dollars committed to funding R&D efforts. To move forward towards renewable energy generation goals requires an informed public and providing policy makers with the information and options necessary.

Since now both energy generation and demand will be dominated by what the weather and climate are doing, it is important that we take advantage of the talent we have in our community of experts to support these efforts. We are only 16 years out from a popular target date (2040) to reach 100% renewable energy generation. That’s not very far away. Communication and the exchange of ideas regarding problems and potential solutions are key to generating public confidence in our abilities to reach these goals within these timelines without disruption to the grid or economic impacts on people’s wallets.

What are some of the barriers to carbon-free energy that the AMS community is poised to help address?

Jeff and John: From a meteorological and climatological perspective, we have pretty high confidence in establishing what the renewable energy resource is in a given area. .. We have, for the most part, developed very good forecasting tools for predicting generation out to the next day at least. But sub-seasonal (beyond a week) and seasonal forecasting for renewables remains problematic. We know that the existing transmission infrastructure needs to be upgraded, thousands of miles of new transmission needs to be built, siting and commissioning timelines need to be shortened, and we need to coordinate the retirement of fossil fuel generation and its simultaneous replacement with renewables to insure grid stability. This panel will discuss some of the potential solutions we have at hand, and what is/are the best pathway(s) forward.

On the other hand, meeting the various state and federal targets regarding 100% renewable energy generation also implicates other unresolved issues, such as: how will we accelerate the necessary mining, manufacturing, and construction and operation by a factor of nearly five in order to achieve these power generation goals? Not to mention how all this is affected by financing, the current patchwork of … regulatory schemes, NIMBY issues, and a constantly changing landscape of policy initiatives (depending on how the political wind is blowing–sorry for the pun!). And of course, there is the question of the “unknown unknowns!”

What will AMS 104th attendees gain from the session?

Nick: Achieving the energy transition is fundamental for the health and success of all societies globally, and indeed, may be one of the defining topics of history books for this time. With that said, the transition to carbon-free energy will not be a straight line, and many factors are important for achieving success. This session should provide an understanding of the current status of our transition, and what obstacles and key questions need to be overcome and answered, respectively, to complete our transition.

Header photo: Wind turbines operating on an oil patch in a wind farm south of Lubbock, Texas. Photo credit: Jeff Freedman.

About the AMS 104th Annual Meeting

The American Meteorological Society’s Annual Meeting brings together thousands of weather, water, and climate scientists, professionals, and students from across the United States and the world. Taking place 28 January to 1 February, 2024, the AMS 104th Annual Meeting will explore the latest scientific and professional advances in areas from renewable energy to space weather, weather and climate extremes, environmental health, and more. In addition, cross-cutting interdisciplinary sessions will explore the theme of Living in a Changing Environment, especially the role of the weather, water, and climate enterprise in helping improve society’s response to climate and environmental change. The Annual Meeting will be held at the Baltimore Convention Center, with online/hybrid participation options. Learn more at annual.ametsoc.org.