By Akanksha Singh, Graduate Student in Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences at the University of Maryland, College Park

Note: This is a guest blog post; it represents the views of the author alone and not the American Meteorological Society or the AMS Policy Program. The Science Policy Colloquium is non-partisan and non-prescriptive, and promotes understanding of the policy process, not any particular viewpoint(s).

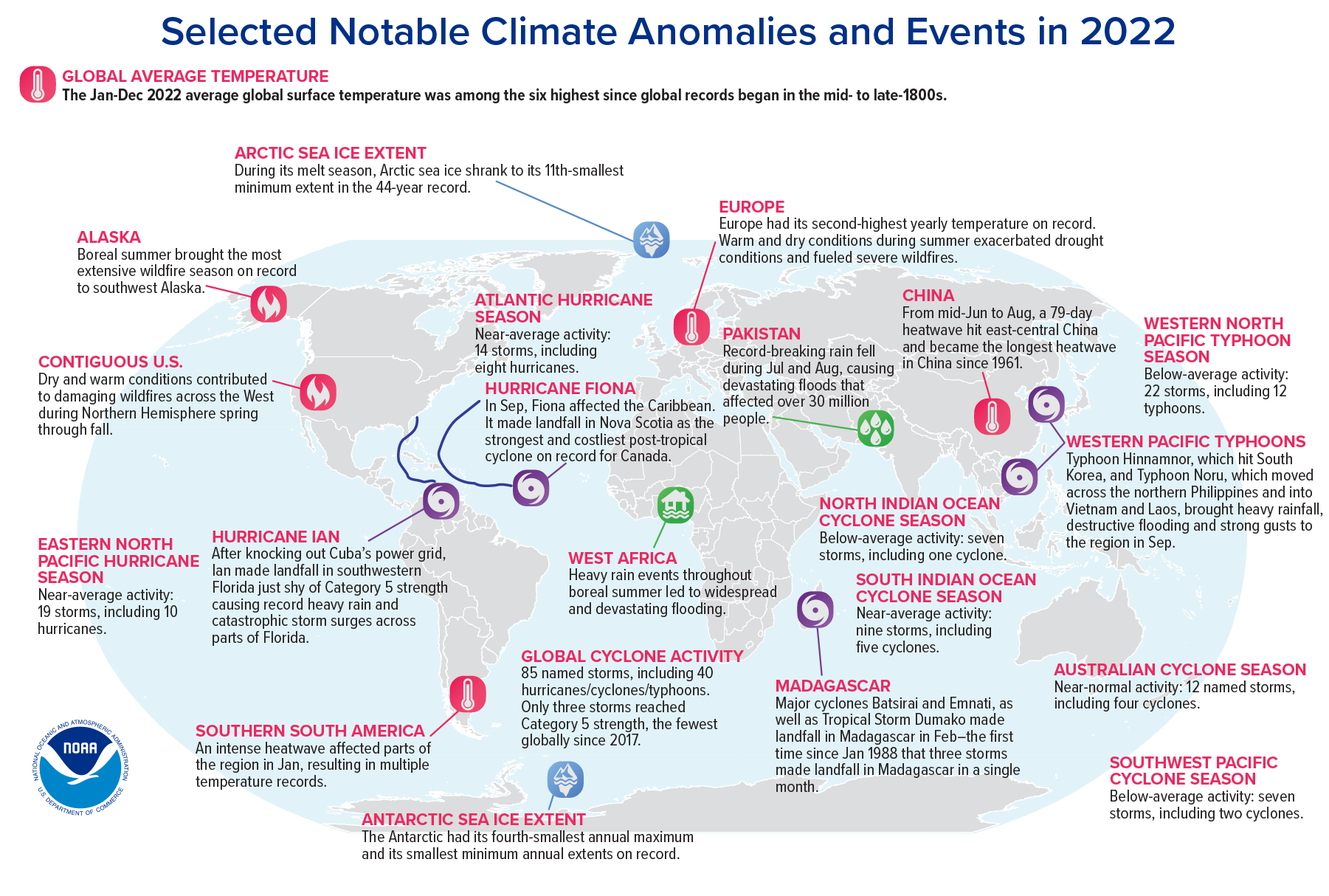

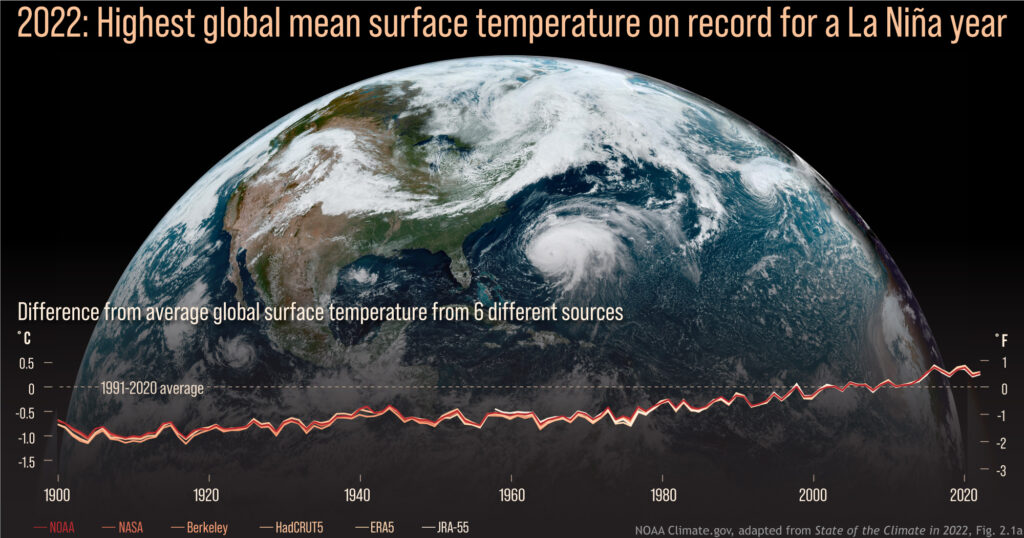

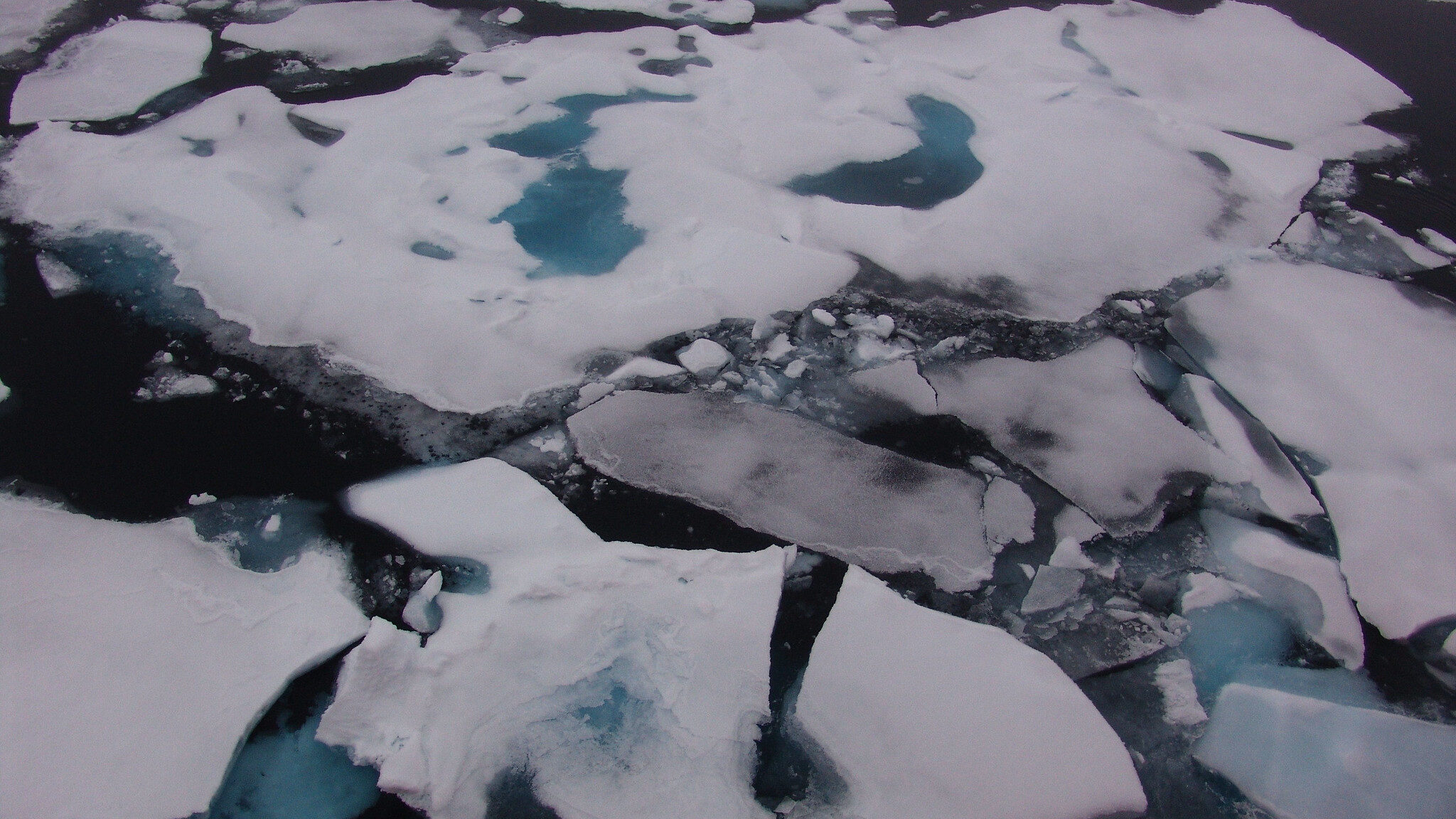

I moved to the United States in 2019 to pursue my PhD in Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences at the University of Maryland. As a scientist, I have always been passionate about the potential of science to positively transform lives worldwide. Growing up and being trained in the Global South, I have witnessed firsthand the profound effects of environmental changes. The Global North (definition) is primarily responsible for the excess CO2 in the atmosphere, considering historical emissions. However, it is the Global South that disproportionately suffers from the impacts of climate change caused by these emissions. This unfair burden underscores the need for environmental justice and policies not only locally but also globally. Therefore, I was excited to attend the AMS Science Policy Colloquium (SPC) to learn how an immigrant scientist like myself can navigate the U.S. policy process and conduct research that helps hold the U.S. accountable for its impact on the Global South.

During one talk, I found myself particularly interested in an account of a famous World War II-era debate between Vannevar Bush, author of “Science, the Endless Frontier,” and West Virginia Senator Harley Kilgore about how government-funded research should be managed and directed. Bush advocated for funding the “best” scientists to pursue research, without specific social aims, whereas Kilgore pushed for more equitably distributed funding for research, with a focus on addressing urgent social problems. Bush’s viewpoint ultimately prevailed, leading to the creation of the National Science Foundation, which emphasizes and advances his merit-based approach.

However, this debate made me wonder: how do we define merit? How do we determine who the “best” scientists are, particularly in the context of climate science? As several speakers noted, research funding and university resources are overwhelmingly concentrated in wealthy, coastal, urban areas. As a result, climate research often fails to fully consider all relevant stakeholders, particularly to the detriment of rural, marginalized, and indigenous populations. How can we ensure that the contributions of indigenous knowledge systems are valued and integrated into scientific research? How do we bridge the rural-urban disparity in research opportunities and resources to foster a more inclusive and comprehensive approach to addressing global challenges like climate change? Can we reimagine how NSF funding is granted to develop a more equitable solution?

Left: Akanksha at the SPC’s 2024 Hooke Lecture in Science and Society (Photo: AMS staff). Right: Akanksha at the U.S. Capitol (Photo: Akanksha Singh).

We also learned a lot about the growing political divide across the United States, and how it has led to a significant decrease in the productivity of both the House and the Senate. The number of swing districts has dwindled significantly, and ideological divisions over relevant topics have grown steep and bitter, raising concerns about the future of science policy and legislature. This subject is particularly pertinent as a number of recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions have limited the authority of federal agencies, most notably the EPA. If federal agencies are increasingly limited in their power to direct science policy, and Congress is too gridlocked to pass necessary legislation, how will we promote and direct scientific advancement as a nation?

Changing topics, I was surprised by many speakers’ focus on China as a significant economic and national security threat, and how these concerns manifested as suspicion of Chinese scientists. While I understand that many of these concerns are valid, as an Asian immigrant and a member of the scientific community, it is upsetting to hear fellow scientists portrayed as a threat. As future policymakers, we must oppose such rhetoric. Immigrant scientists have significantly advanced American science and form the backbone of our scientific community. Targeting them with suspicion and xenophobic rhetoric is not only unjust but also detrimental to our scientific progress.

That being said, I appreciated other speakers’ suggestions that we view China as the most important international scientific collaborator for the United States, and that the best scientific advancements come from collaboration and a sense of global good. I agree that changing our attitudes towards China and advancing science peacefully should be our goal, especially when forming policies to combat climate change. Climate change does not differentiate between nationalities and it does not respect borders; as scientists, neither should we.

I was struck by one thing I felt was missing from the SPC: there was no discussion of the military-industrial complex, its impact on science policy, and how relying on for-profit defense contractors for funding will never lead to equitable scientific advancements. While I understand the need for private investments, I think it’s high time we push for the triple bottom line—economic, social, and environmental considerations—when calculating the success of a project, rather than focusing solely on economic profitability, especially when these ventures ultimately profit from conflict and involve large amounts of unregulated and untracked greenhouse gas emissions.

Overall, I had a fantastic time at the AMS Science Policy Colloquium. It was truly a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to engage with a diverse group of individuals involved in the formidable U.S. science policy space. It was also wonderful to interact with fellow attendees, fostering collaborations and connections that will last a lifetime. I’ve gained a deeper appreciation for the challenges of science policy and have come to recognize the importance and necessity of compromise in achieving progress. My research focuses on understanding tropospheric ozone chemistry and conveying that into policy-relevant tropospheric ozone reduction strategies. In this regard, the SPC has helped me understand the priorities of key stakeholders in the policy making and implementation process, as well as the importance of translating scientific research into policy directives. This SPC has also encouraged me to pursue a career in science policy and/or environmental justice post-PhD.

Last but not least, I would like to thank the people who made this colloquium possible: Paul Higgins, Emma Tipton, and Isabella Herrera, for their passion and commitment in creating such a rich environment of learning opportunities and experiences.

Featured image: Akanksha Singh, second from left, with her SPC legislative exercise working group. (Photo courtesy of Akanksha Singh).

About the AMS Science Policy Colloquium

The AMS Science Policy Colloquium is an intensive and non-partisan introduction to the United States federal policy process for scientists and practitioners. Participants meet with congressional staff, officials from the executive office of the President, and leaders from executive branch agencies. They learn first-hand about the interplay of policy, politics, and procedure through legislative exercises. Alumni of this career-shaping experience have gone on to serve in crucial roles for the nation and the scientific community including the highest levels of leadership in the National Weather Service, the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP), the National Science Foundation, and the U.S. Global Change Research Program (USGCRP), and AMS itself.