Imagine being awoken late one night by the near constant glow of lightning overhead—often flickering silently but occasionally rumbling deeply with a strike nearby. Then it happens the same time the next night—and the next, and the next, sometimes lasting for many hours at a time.

Now imagine the nocturnal fireworks happening nearly 300 days per year.

Welcome to Lake Maracaibo, Venezuela.

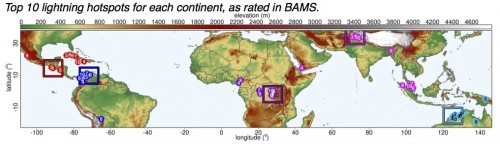

Based on a scientific paper just released by the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society (BAMS), the Lake Maracaibo region is the newly crowned lightning capital of the world, taking the throne from a celebrated thunderstorm-prone region of Africa.

Lake Maracaibo, the largest lake in South America, is already well known for its lightning. Boats take tourists onto the water to watch the storms, and the flag of the region—the State of Zulia—features a lightning bolt in honor of the lake’s prolific displays.

Nonetheless, Africa’s Congo Basin had previously been identified by scientists as the world’s lightning hotspot. It stayed that way for several years until the new BAMS article (available online) recalculated rankings based on a new, high-resolution dataset of satellite observations of the lightning flash-rate density.

Lake Maracaibo’s pattern of convergent wind flow–mountain–valley, lake, and sea breezes–occurs over warm lake waters nearly year-round and contributes to nocturnal thunderstorm development 297 days per year on average, with a peak in September. These thunderstorms are very localized and their persistent development anchored in one location accounts for the high flash-rate density. While practically the whole lake is averaging 50 flashes per year, only a small portion qualifies as the world leading hotspot, with more than 232 flashes per square kilometer per year (including cloud-to-ground and cloud-to-cloud lightning).

The BAMS article, “Where are the Lightning Hotspots on Earth?” by Rachel I. Albrecht, Steven J. Goodman, Dennis E. Buechler, Richard J. Blakeslee, and Hugh J. Christian, is derived from 16 years of observations by the Lightning Imaging Sensor aboard the now defunct NASA Tropical Rainfall Measurement Mission satellite.

The team—representing the University of Maryland, Universidade de São Paulo (Brazil), NOAA, NASA, and the University of Alabama in Huntsville—cites several factors for the new lightning champion, including its unique geography and climatology. Storms mostly form during the nighttime hours, after the tropical heating of the day allows warm Caribbean air to mix with colder Andes Mountain air. According to the article, “Nocturnal thunderstorms over Lake Maracaibo are so frequent that their lightning activity was used as a lighthouse by Caribbean navigators in colonial times.”

The authors noted that previous studies, using the same satellite capabilities, missed the localized peak at Lake Maracaibo for several reasons. Coarser resolution was one problem (the new study partitions the lake into 20 times more sectors than earlier studies), but so were filtering of high-density outbursts of lightning and calculations made to compensate for limited samples of sparse lightning areas. Where the previous studies were aimed at getting the first useful global overviews, the new study is calibrated to identify hotspots.

Located near the border of the Congo and Rwanda, the now second-ranked Kahuzi-Biéga National Park in Kabare has its own mountainous geography that allows five different locations in the region to rank in the top 10 for lightning flash-rate density. Previous research had shown that the Congo basin boasted the largest flash rate per thunderstorm, and the region still has the world’s largest average flash rate density for any particular part of the day. It averages 5.5 flashes per hour at about 5:30 p.m. local time within a 1° latitude x 1° longitude box. That rate is nearly matched by Lake Maracaibo averaging more than 5.4 flashes per hour at about 3 a.m., when nighttime winds descending the mountain valleys converge over the ever-warm lake waters.

Both of the top two hotspots have lengthy lightning “seasons” but neither had a peak spell matching the 90 flashes per day in early August in the 1° x 1° region of Majagual, Colombia.

Before satellite observations were available, scientists estimated that the whole Earth at any one time experienced about 100 flashes per second. Satellite evidence has reduced that estimate to about 44 to 46 flashes per second, which means Earth experiences nearly 1.4 billion lightning flashes per year. The rate is 20% higher during Northern Hemisphere summer. This variation is in part due to the larger amount of land north of the equator, which lends itself to the surface heating that fuels thunderstorms.

The new BAMS study confirms previous findings showing that lightning activity tends to happen at night in areas closer to mountain ranges and/or coasts but continental-wide lightning activity peaks during the afternoons. And yet the new king of lightning is over water and peaks at night.

The new list of the world’s top 10 lightning flash-rate density hotspots (shown below) includes no sites from North America. Four locations, in Guatemala, Cuba, and Haiti, had more than 100 flashes per square km per year (led by 117 in Patulul, Guatemala). The most lightning prone U.S. location, ranked 122nd globally, was in the Everglades not far from Ft. Myers, Florida, with 79 flashes per square km per year.

|

World rank

|

Flash-rate density

|

Location

|

|

1

|

232.52

|

Lake Maracaibo, Venezuela |

|

2

|

205.31

|

Kabare, Dem. Rep. of Congo |

|

3

|

176.71

|

Kampene, Dem. Rep. of Congo |

|

4

|

172.29

|

Caceres, Colombia |

|

5

|

143.21

|

Sake, Dem. Rep. of Congo |

|

6

|

143.11

|

Dagar, Pakistan |

|

7

|

138.61

|

El Tarra, Colombia |

|

8

|

129.58

|

Nguti, Cameroon |

|

9

|

129.50

|

Butembo, Dem. Rep. of Congo |

|

10

|

127.52

|

Boende, Dem. Rep. of Congo |

Flash-rate density indicates the average number of times lightning flashes each year over an area 1 square kilometer in size.