by Bob Henson, AMS Councilor and Chair, AMS Committee on Environmental Stewardship (ACES)

Those of us involved with climate change in our professional lives—researchers, educators, authors, students—often feel the need to “walk the walk” in a demonstrable way. AMS is one of the world’s premier organizations involved with peer-reviewed research on our changing atmosphere, so it’s only fitting that the Society is finding ways to demonstrate its environmental bona fides in its own operations. For example, AMS has been a leader this past decade in working toward “green meetings.” An upcoming BAMS article will feature some green-meeting highlights, and a summary can also be found in the “About AMS” section of the AMS website.

Just in time for the Society’s 100th birthday, AMS has now ensured that the electricity supply in its offices in Boston and Washington, D.C., is effectively 100% renewable. The Boston shift involved working with the nonprofit Green Energy Consumers Alliance (GECA), a spinoff of Massachusetts Energy that works to maximize the use of renewables in the state’s electricity supply.

AMS recently finalized a renewable two-year agreement (retroactive to January 2019) to purchase Class I renewable energy certificates (RECs) from GECA. These certificates are equal to the full amount of electricity consumed at the AMS buildings at 44 and 45 Beacon Street. Each certificate mandates the production of one megawatt hour of renewable energy, documenting where, how, and when the energy (in this case, wind energy) was produced. In 2019, energy providers in Massachusetts were required to purchase in-state Class I RECs for 14% of all electricity they generate, a percentage that goes up each year by 1%. When entities such as AMS also purchase Massachusetts Class I RECs, it further stimulates the market for clean energy. In other words, Massachusetts Class I RECs don’t simply buy green energy that is already government-mandated; they actually promote the creation of new green-energy supplies within the state.

AMS Controller Joe Boyd worked with the AMS Committee on Environmental Stewardship (ACES) to research options for renewable energy at the Boston building and shepherded the final agreement with GECA.

“Given the Society’s strong commitment to environmental issues, it was natural that we include 100% renewable electricity sourcing to our efforts to maintain a small carbon footprint,” says AMS Executive Director Keith Seitter.

In Washington, AMS leases office space within the headquarters of the American Association for the Advancement of Science at 1200 New York Avenue NW. This building’s electrical supply is also effectively 100% renewable, via RECs that are purchased through a Constellation New Energy contract for transmission and generation. (The RECs do not include electric distribution, and the building also uses a small amount of natural gas.)

“ACES continuously strives to promote the Society’s environmentally progressive standards, complementing the research and efforts of AMS members. Thanks to felicitous timing, the Society is celebrating its transition to 100% renewable energy on its 100th anniversary,” says incoming 2020 ACES Chair C. Todd Rhodes (Coastal Carolina University).

climate change

It Used to Be "Inadvertent Climate Modification," Too

AMS Executive Director Keith Seitter sent a letter today to President Trump. It begins,

In an interview with Piers Morgan on Britain’s ITV News that aired Sunday, 28 January, you stated, among other comments:

“There is a cooling, and there’s a heating. I mean, look, it used to not be climate change, it used to be global warming. That wasn’t working too well because it was getting too cold all over the place”

Unfortunately, these and other climate-related comments in the interview are not consistent with scientific observations from around the globe, nor with scientific conclusions based on these observations. U.S Executive Branch agencies such as NASA and NOAA have been central to developing these observations and assessing their implications. This climate information provides a robust starting point for meaningful discussion of important policy issues employing the best available knowledge and understanding.

Read the whole letter here.

In response to the BBC interview, Bob Henson of Weather Underground’s Category 6 blog gave a detailed debunking of the President’s comments. It’s a useful read for those wanting to parse out the persisting misunderstandings about the climate change discourse.

One misconception Henson clarifies is the talking point about which came first, “climate change” or “global warming.”

The history of the phrases “climate change” and “global warming” is much more interesting than Trump gives it credit for. Researchers were using climatic change or climate change as far back as the early 20th century when writing about events such as ice ages. Both terms can describe past, present, or future shifts—both natural and human-produced—on global, regional, or local scales.

Climate change is a general term that has applied over the years to many forms of climate change. Per the AMS Glossary:

Any systematic change in the long-term statistics of climate elements (such as temperature, pressure, or winds) sustained over several decades or longer.

It applies to both natural and human-caused changes (and “anthropogenic climate change” gets its own Glossary entry).

Obviously, the term still applies. So does “global warming.” In 2018 already, “global warming” is in the title of several scientific papers accepted to AMS journals.

Henson traces the first usage of “global warming”—a term specific to the observed climate trend—to a paper by Wallace Broecker in the 8 August 1975 issue of Science.

This may indeed be the first paper to apply “global warming” to a changed worldwide condition, via carbon dioxide release. Broecker was writing in anticipation of this trend becoming an observed fact, surpassing the then-prominent cooling influence of dust and pollutants as

the exponential rise in the atmospheric carbon dioxide content will tend to become a significant factor and by early in the next century will have driven the mean planetary temperature beyond the limits experienced during the last 1000 years

The idea that the Earth would warm as a whole, if not in every locale or region, was not new at the time of Broecker’s paper. In 1971, the National Academy of Sciences had included an objective to study the “effect of increasing carbon dioxide on surface temperatures” in its report, “The Atmospheric Sciences and Man’s Needs” (summed up by Robert Fleagle in BAMS that year).

The term “global warming” itself appears in AMS journals at least five years before Broecker’s paper. Jacques Dettwiller addressed the means of collecting long term global temperature records in the February 1970 Journal of Applied Meteorology. Lamenting the difficulty of separating out urban heat island effects, Dettwiller advocated monitoring deep soil temperatures, which seemed to “afford a means to monitor the global increase in temperature during the first half of the 20th century.”

For our purposes, it’s a landmark paper in the way Dettwiller cited a 1964 paper in Monthly Weather Review by Stanley Changnon that used such techniques in rural Urbana, Illinois: Changnon, wrote Dettwiller, “was able to discern values for global warming….”

At the time, the “current” term for global warming or anthropogenic climate change through the greenhouse effect was actually, ”Inadvertent Climate Modification.” That was the title of a 1971 report by an international group of climatologists convened by MIT and the Royal Swedish Academies for a “Study of Man’s Impact on Climate.” It was one of the first large consensus reports to warn of sea level rise, polar ice cap melt, major Arctic warming, and more.

After nearly a half century of highly prominent scientific warnings, a word was indeed dropped from the climate lexicon because it no longer made sense. That word was “inadvertent.”

Withdrawal from the Paris Agreement Flouts the Climate Risks

by Keith Seitter, AMS Executive Director

President Trump’s speech announcing the U.S. withdrawal from the Paris Climate Agreement emphasizes his assessment of the domestic economic risks of making commitments to climate action. In doing so the President plainly ignores so many other components of the risk calculus that went into the treaty in the first place.

There are, of course, political risks, such as damaging our nation’s diplomatic prestige and relinquishing the benefits of leadership in global economic, environmental, or security matters. But from a scientific viewpoint, it is particularly troubling that the President’s claims cast aside the extensively studied domestic and global economic, health, and ecological risks of inaction on climate change.

President Trump put it quite bluntly: “We will see if we can make a deal that’s fair. And if we can, that’s great. And if we can’t, that’s fine.”

The science emphatically tells us that it is not fine if we can’t. The American Meteorological Society Statement on Climate Change warns that it is “imperative that society respond to a changing climate.” National policies are not enough — the Statement clearly endorses international action to ensure adaptation to, and mitigation of, the ongoing, predominately human-caused change in climate.

In his speech, the President made a clear promise “… to be the cleanest and most environmentally friendly country on Earth … to have the cleanest air … to have the cleanest water.” AMS members have worked long and hard to enable such conditions both in our country and throughout the world. We are ready to provide the scientific expertise the nation will need to realize these goals. AMS members are equally ready to provide the scientific foundation for this nation to thrive as a leader in renewable energy technology and production, as well as to prepare for, respond to, and recover from nature’s most dangerous storms, floods, droughts, and other hazards.

Environmental aspirations, however, that call on some essential scientific capabilities but ignore others are inevitably misguided. AMS members have been instrumental in producing the sound body of scientific evidence that helps characterize the risks of unchecked climate change. The range of possibilities for future climate—built upon study after study—led the AMS Statement to conclude, “Prudence dictates extreme care in accounting for our relationship with the only planet known to be capable of sustaining human life.”

This is the science-based risk calculus upon which our nation’s climate change policy should be based. It is a far more realistic, informative, and actionable perspective than the narrow accounting the President provided in the Rose Garden. It is the science that the President abandoned in his deeply troubling decision.

For Climate Science, Transitions Continue

The Inauguration of Donald Trump yesterday marked the end of the Transition. Yet, the end of the Transition with a big “T” marks the beginning of small “t” transitions for everyone else—political winners and losers alike.

According to Reed College historian Joshua Howe, climate science is particularly affected by such changes, absorbing and adapting to shifts in political winds for many decades. The continually transitioning relationship climate science has forged with politics—especially environmental politics—is chronicled in Howe’s book, Behind the Curve: Science and the Politics of Global Warming (Univ. of Washington Press, 2014).

As a past recipient of the AMS Graduate Fellowship in the History of Science, Howe presented the basics of his book at the 2009 AMS Annual Meeting. His dissertation was expanded into the book. In a recent interview at New Books Network (listen here), Howe explains how climate scientists have had to reinvent their approach to environmental advocacy. In Howe’s view, the approach politically active scientists took to triggering action on climate change simply didn’t work well, making the field ripe for further transition.

It was clear early on that climate change, as an environmental concern, was unprecedented in scale and complexity. Following on the debate in the 1970s over the nation’s Supersonic Transport program, atmospheric science had won a place at the environmental table. But environmentalists were used to dealing with local pollution and wilderness access—clear quality of life issues that resonated with their middle class constituency, Howe says. They were interested in concrete, simple, nontechnical issues they could rally around—and climate change was too complex to fit those parameters. Climate change wasn’t a low-hanging fruit ripe for political victories.

Meanwhile, the issue of nuclear winter provided a further, politically loaded impetus to the climate community, Howe said. But the result was a split, with some scientists becoming more politically outspoken within the environmental movement, while others became more entrenched within a conservative physical science community. As a result, the relationship of government funding to climate science became politically fraught.

Scientists initially reached out on climate change through the government agencies in the 1970s. Howe points out that “working within government bureaucracies left scientists vulnerable to political change.” The Carter administration shifted directions; Reagan then arrived with budget cuts and curtailed access to bureaucracy.

In response, many climate scientists sought a technical consensus that might force political action by the shear power of knowledge. The scientists attacking the problem in the 1970s onward had, as Howe puts it, a “naïve” attitude.

“Better knowledge, climate scientists believed, would lead to better policy,” Howe said in his 2009 AMS presentation. “Perhaps it is time for scientists to drop the false veil of political neutrality and begin discussing science and politics as two sides of the same coin.”

The AMS Annual Meeting in Seattle is an ideal opportunity to ponder the future of the atmospheric sciences during the next four years. Check out the Monday Town Hall on “Climate Change – How can we make this a national priority?” (12:15 p.m., Room 613). Then attend the panel session on priorities of the Trump Administration and Congress later that day (4 p.m., same room). The panelists include Ray Ban, Fern Gibbons, and Barry Lee Myers.

New Survey Shows AMS Members' Positions on Climate Change

The vast majority of members of the American Meteorological Society agree that recent climate change stems at least in part from human causes, and the agreement has been growing significantly in the last five years.

According to a new survey of AMS members, 67% say climate change over the last 50 years is mostly to entirely caused by human activity, and more than 4 in 5 respondents attributed at least some of the climate change to human activity.

Only 5% said that climate change was “largely or entirely” due to natural events (while 6% said they “didn’t know.”)

The findings are from the initial results of a 2016 national survey of more than 4,000 AMS members just released today by George Mason University. The joint GMU/AMS study was conducted in January with support from the National Science Foundation.

Four in five respondents say their opinion on the issue has not changed over the last five years, but of the 17% who did shift, 87% said they feel “more convinced” now that human-caused climate change is happening. Two-thirds of them based this change on new scientific information in the peer-reviewed scientific literature, although in general respondents report basing these changes on multiple sources of information, such as peers and personal observation. Indeed, 74% think that their local climate has changed in the past 50 years.

AMS membership is largely constituted of professionals in the weather, water, and climate fields. One-third of the respondents hold a Ph.D. in meteorology or the atmospheric sciences, and overall just more than half have doctorates in some field.

Yet, while highly educated, the AMS membership represents a different selection of the profession than the climate-expert community commonly cited in statistics about the scientific consensus on climate change. Only 37% of AMS respondents self-identified themselves as climate change experts.

As a result, despite the growing agreement among the membership, there are differences in the results of the new survey compared to the position of climate scientists reflected in the reports of the IPCC.

On one key basic point the difference between the climate expert community and the AMS community as a whole is nearly negligible: AMS members are nearly unanimous (96%) in thinking that climate change is occurring and almost 9 in 10 of them are either “extremely” or “very” sure of this change. Only 1% say climate change is not happening.

However, the AMS Statement on Climate Change, which basically reflects the IPCC findings, not only says “warming of the climate system now is unequivocal” but also says, “It is clear from extensive scientific evidence that the dominant cause of the rapid change in climate of the past half century is human-induced increases in the amount of atmospheric greenhouse gases.” The new survey shows the AMS community as a whole is still moving toward this state of the science position. Furthermore, the new GMU/AMS survey does not probe members’ views on specific mechanisms of human-caused climate change.

Full results of the survey, including what members think of the future prospects for climate change, are posted here.

2015: The Hottest Hiatus

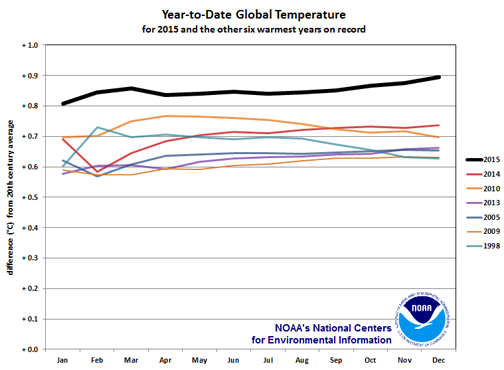

It was predicted early and often—and now, finally, it’s official. Throughout 2015, climate-watchers at NOAA and NASA were giving indications that the world’s surface temperature was going to top every annual mean measured since records began in 1880. Today, the two agencies with independent analyses jointly confirmed that global surface temperatures in 2015 blew away the record set in 2014.

The mean global temperature in the analysis by NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies was 0.13°C above the 2014 record, and NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information had it as 0.16°C above. In all, according to NCEI, 2015 was 0.90°C above the 20th-century average.

The temperature record was no surprise, even though 2015 set a new record by the largest margin ever recorded. In the horse race of annual temperatures, 2015 jumped out of the gate ahead of the pack and never looked back at previous record holders like 1997, 2005, and 2014 (see the NOAA graphic below). It was a wire-to-wire victory in which 10 of 12 months were the hottest ever on record for their respective periods. Indeed, going into the homestretch, NCEI pointed out that December 2015 would have to stumble to more than 0.81°C below average to avoid setting a record. Instead, December extended the year’s lead by registering 1.11°C above the 1880-2015 century average—in other words, it was the hottest month in the century-plus of measurement history.

Inevitably, the question arises: does this record conflict with the notion of a “hiatus,” which the IPCC addressed in its Fifth Assessment Report in 2013? Trend aside, 15 of the 16 hottest years on record have occurred in this still-young 21st century, according to NASA; NOAA says four different years in that brief period have now reset the global surface temperature record.

Not surprisingly, a decade or so is a mere blip in climatology terms, and the short-term trend of global warming depends on where you mark the start and end point of your analysis. The warming has been relatively fast since 1970—about 0.16 or 0.17°C per decade, depending on your dataset. If you just look at only 1998-2012, as IPCC did, during sustained warmth near record levels, the upward trend is half what it is over the longer period. Of course, starting with 1998 means starting out very warm—hence a trend with major handicapping.

As a result, there’s been scientific backlash against use of the term “hiatus.” As Stephan Lewandowsky, James Risbey, and Naomi Oreskes point out in a newly released article in BAMS, the word doesn’t fit:

The meaning of the terms “pause” and “hiatus” implies that the normal fluctuations in warming rate have been surpassed such that warming has stopped.

They show that warming looks slower or faster depending on the start date of any given 15-year period, but that none of the slowest-warming periods, including the last 15 years, is any slower than one might expect in a warming climate post-1970 (or indeed less remarkable with longer periods one might choose). They conclude,

The “pause” is not unusual or extraordinary relative to other fluctuations and it does not stand out in any meaningful statistical sense.

Lewandowsky and colleagues go on to show that, objectively, “hiatus” doesn’t pass the eye test. When tested by looking at a curve resembling the global temperature curve, experts and nonexperts alike perceived a long-term, uninterrupted upward trend. The authors conclude that misuse of the word “hiatus” distorts how the data look, and thus impedes not only public perception of global warming but also scientific work.

One benefit of the “hiatus” talk is that scientists have been motivated to ask more questions about the normal short-term fluctuations of climate. One purpose of the Community Earth System Model’s Large Ensemble Project, for example, is to produce large numbers of climate model simulations to help “disentangle” model error from internal climate variability—that is, the fluctuations caused by climate irrespective of anthropogenic forcing.

In an article in the August issue of BAMS, the ensemble project’s investigators show a sample experiment in which the slower warming of the last 15 years has actually been a pace well within normal variability, with or without greenhouse gas forcing (see figure below).

As the world continues to warm, this year’s record is prone to fall. Meanwhile, the ensemble also shows that the odds of a 10- or 20-year fluctuation stopping the warming—let alone a brief cooling—keeps getting tinier and tinier.

Letting Scientists Benefit Us All

Lately you may have noticed that AMS has garnered media attention by standing up for NOAA scientists who are the focus of Congressional scrutiny. This scrutiny was initiated after the scientists re-analyzed global surface temperatures with newly corrected data and found that the warming trend of the second half of the 20th century has been continuing unabated since 1998 instead of experiencing what sometimes has been portrayed as a warming “hiatus.”

AMS doesn’t step casually into political arenas. As a non-profit scientific and professional society, we remain solidly grounded in the world of science. We help expand knowledge and understanding through research and, as our mission states, we work to ensure that scientific advances benefit society. We engage the policy process to help inform decision making and to help ensure that policy choices take full advantage of scientific understanding.

This case is slightly different, however, because the scientific process itself is at risk. When the scientific process is disregarded or, worse yet, possibly derailed, a political issue can become an AMS issue.

The scientific process that AMS and other like-minded institutions have championed over the centuries is about taking careful observations, conducting controlled experiments, separating personal opinions and beliefs from evidence, and, perhaps most critically, exposing scientific conclusions to rigorous and repeated testing over time by independent experts. These repeated cycles of distribution and “trial by fire” happen most notably at meetings, in peer-review, and in publication.

Crucially, the process systematically removes as much as possible of our human tendency to see what we want to see and puts the burden of proof on reproducible steps. It is a disciplined, particular way of finding truths, no matter how elusive, while rendering biases, opinions, and motivations as irrelevant as possible.

This systematic approach to separating fact from opinion occasionally goes astray, of course, but its iterative nature means that science is continually self-correcting and improving; better data and understanding ultimately replace older thinking. Science encourages people to question and challenge thinking, certainty, and accuracy—but it requires they focus exclusively on what they can detect and measure and reason.

Even though all the data, logic, and methodologies are publicly available, the paper rejecting the global warming hiatus inspired Congressional requests for additional email and discussions. Asking for these correspondences—especially from scientists themselves—can easily weigh down the ingenious process by which science has continually advanced. And so AMS made public statements in favor of letting science freely work its wonders. It’s not the first time AMS has done so, and it probably won’t be the last.

We owe much of modern prosperity to an unencumbered scientific process, and it continues to provide some of the most profound and dramatic advancements in the world. This includes medicine, biology, chemistry, computing, agriculture, engineering, physics, astronomy, and, of course, meteorology, hydrology, oceanography, and climatology. Every one of us benefits every single day from what scientists have learned, shared, and provided.

And that’s yet another reason why occasionally AMS must speak out—because of our mission “for the benefit of society.” The point is not just to protect science but also to protect the benefits that knowledge can provide to all of us, no matter what we think of the results. In this, our scientific society actually has much in common with the politicians and policy makers in Washington, D.C.

AMS stands behind the scientific process and will defend that process when necessary, but our goal is to work with policy makers to promote having the best knowledge and understanding used in making policy choices.

From Florida, A Reminder About Freedom of Expression

The Florida Center for Investigative Reporting published allegations this week that the terms “climate change” and “global warming” were banned from state government communications in Florida, including state-agency sponsored research studies and educational programs. The Washington Post followed with claims, for example, that a researcher was required by state officials to strike such words before submitting for publication a manuscript about a epidemiological study.

No evidence of a written policy or rule has been reported, and state officials have denied any policy of the sort. Meanwhile, the media are hunting through Florida websites trying to find state documents produced during the administration of Gov. Rick Scott with contents that would contradict the charges of an unwritten policy, imperfectly enforced.

The controversy is one in a string of recent events reminding us how much scientists rely on their freedom of expression. Most often the problem has been the freedom of government scientists to speak about their work with the public. Lately this has caused a media blizzard in Canada.

Science ethicists may argue one way or another about where the limits of public expression are for government scientists when they contradict policy goals. And certainly—as well seen most obviously in the Cold War—such goals can include national security concerns. But the AMS stance on the filtering or tampering of science for nonscientific purposes is quite clear in the Statement on Freedom of Expression:

The ability of scientists to present their findings to the scientific community, policy makers, the media, and the public without censorship, intimidation, or political interference is imperative.

Freedom of expression is essential to scientific progress. Open debate is a necessary part of science and takes place largely through the publication of credible studies vetted in peer review. Publication is thus founded on the need for freedom of expression, and it is in turn a manifestation of freedom of expression.

One might think the job of journals is to screen out unwanted science, but it’s quite the opposite. Papers are published not because they are validated as “right” so much as they are considered “worthy” of further scientific consideration. In addition, the publication process itself—which AMS knows well in its 11 scientific journals—is not just for authors to report and interpret their work. It relies on free discussion. The peer review process usually allows reviewers maximum protection of anonymity to preserve the ability to speak freely about the manuscripts being scrutinized. The papers that pass review are then the starting point for documenting objections, alternative interpretations, and confirmation, among other expressions that only matter if made accessible to other scientists through peer reviewed journals.

The AMS Statement recognizes that such freedom implies responsibility:

It is incumbent upon scientists to communicate their findings in ways that portray their results and the results of others, objectively, professionally, and without sensationalizing or politicizing the associated impacts.

Scientists are not the only ones to treasure such freedoms, of course. Society benefits from the progress of science every day. This only happens when scientists freely, promptly, and prolifically report what they find—and that means exactly what they find, not what they are told to find. The alternative is to compromise the pursuit of truth and the very foundations of our health and prosperity.

We all become victims when science is not shared and cannot flourish. The fact that climate change has deep social, economic, and political implications today means it is even more important to recognize that with increasing value of climate change science comes the increasing temptation for policy makers to co-opt and alter that science. As the AMS Statement warns, the principles of free expression “matter most—and at the same time are most vulnerable to violation—precisely when science has its greatest bearing on society.”

AMS Presidential Town Hall Meeting to Stress Adaptation, Resilience to Climate Change

In weather forecasting, the past is often a harbinger of the future. In a rapidly urbanizing world facing climate change, however, the future looks less and less like the past. With a theme of Building, Sustaining, and Improving our Weather and Climate Hazard Resilience, we’re facing this problem head on at the AMS Annual Meeting, nowhere more so than in tonight’s Presidential Town Hall Meeting (7:00–8:30 p.m., Room C111 of the Georgia World Congress Center).

The speakers include FEMA Administrator Craig Fugate and an IPCC coordinating lead author, Donald Wuebbles—two key figures in communicating climate change hazards and adaptation. Helping all to visualize extremes in the weather will be NCAR’s Mel Shapiro—a master at telling a tale through stunning imagery. This time his tale is Superstorm Sandy, which crashed ashore in the Northeast in fall 2012 with deadly fury. Sandy exposed just how vulnerable our nation is to natural disasters. Storm surge flooding didn’t just wreck the beaches, our playgrounds at the shore. Seawater rushed inland, flooding airports and mass transportation routes and partially disconnecting the biggest city in America—and financial heart of the nation—from its neighbors. The price tag was enormous.

You’ll hear a lot at the Town Hall about how weather- and climate-driven disasters in America are costing us more and more. Multibillion-dollar weather disasters, once consisting solely of major hurricanes and extended drought, are becoming common—even from small-scale thunderstorms. With a climate that’s heating up–resulting in an increase in extreme weather, as Wuebbles will discuss–so too will we see an increase is such megadisasters.

Wuebbles’ playbook on Monday will be the fifth assessment report (AR5) of climate change by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Wuebbles was coordinating lead author of the Working Group 1 section, which was released in full form last week. He says he plans to overview its findings with “an emphasis on our state of understanding of severe weather events under a changing climate.” The presentation will include a preview of the U.S. National Climate Assessment to be released in April.

Wuebbles, who is an atmospheric science professor at the University of Illinois, will also report from a series of NOAA workshops evaluating attribution science (in BAMS here, here, and here), which currently supports making useful projections on some but not all types of severe-weather events. Projections of heat waves and cold spells as well as heavy precipitation events are now possible, and “meaningful trends in floods and droughts” are also discernible by region in the United States. Confidence in an increase in hurricane intensity as the climate warms is also growing. But forecasts of how climate change will affect severe thunderstorms and tornadoes, which in recent years have broken into the billion-dollar disaster range, remain out of reach for now, Wuebbles says, but he adds, “By the next assessment we may be able to make stronger statements.”

Even without the financial burden, today’s weather disasters are becoming debilitating. Look no further than last week’s shutdown of Atlanta due to a well-forecast snowfall. It shouldn’t have happened—particularly since the city went through the same thing just three years ago (January 2011), only with a slightly heavier snowfall. No one thought it could happen again, but it did.

Our ability to successfully communicate is challenged most when disaster strikes. That’s where Fugate comes in. As the top emergency manager in the nation, his job is to organize meaningful and rapid response, which relies on successful communication.

The key is to organize lines of communication beforehand, so when the weather becomes extreme, the avenues of information will remain open. But there are other forms of disaster response. Fugate sees resilience to disaster through increasing adaptation as the way forward in a changing climate. By reducing the risk, he believes we can manage to recover more quickly from extreme weather events. Most importantly, in his view, is to turn victims of disaster into what he prefers them to be called: survivors. He encourages neighbors and communities to get better at coming together when disaster occurs and to help each other overcome the odds and survive.

As AMS Associate Executive Director Bill Hooke explains in Sunday’s Living on the Real World column, there are many levels of disaster response, and all of them “need to be mastered.” When disaster strikes a community, its residents probably will look to the top command-and-control such as FEMA to make things right. But at the other end of disaster response is personal responsibility. Each of us has the task before us to take action to improve our situation. We can wait for disaster to strike, but better would be to plan now how to adapt and make ourselves resilient to weather and climate hazards so they won’t turn into catastrophes.

BAMS Report Editors Named "Leading Thinkers" of 2013

The September issue of BAMS included a special supplement, “Explaining Extreme Events of 2012 from a Climate Perspective,” edited by Thomas Peterson, Martin Hoerling, and Stephanie Herring of NOAA and Peter Stott of the UK Met Office. This was the second edition of this annual investigation of the causes of recent extreme events. The supplement consists of short, concise studies by various author teams and thus serves as a demonstration of the latest methodologies for attributing specific events to longer term trends in climate. For their work on the report, Peterson, Hoerling, Herring, and Stott are lauded in this month’s issue of Foreign Policy magazine as “Leading Global Thinkers of 2013.”

Foreign Policy called the report “a breakthrough in climate science” for connecting extreme events like Hurricane Sandy to human-influenced climate change. The magazine praised the report’s four editors for “point[ing] problem-solvers in the right direction” on better understanding the causes of extreme weather and climate events. Upon learning about the honor, the four noted that the recognition highlights the value that studying extreme events can provide to global security and sustainability.

“It is clearly an acknowledgement that attribution of extreme events is an important scientific topic—that the results of event attribution research can help guide real-world, climate-smart actions,” Peterson told Climate.gov.

The editors also noted that the tribute “honors the collective effort” of all climate scientists studying extreme events, and specifically the 18 different research groups that contributed to the BAMS report. Of course, extreme events will be a featured topic at the AMS Annual Meeting in Atlanta in February, as the theme of the meeting is “Extreme Weather–Climate and the Built Environment: New Perspectives, Opportunities, and Tools.”

Foreign Policy‘s 100 Leading Global Thinkers of 2013 are divided into 10 categories ranging from “the innovators” and “the healers” to “the artists” and “the decision-makers.” The coeditors of the BAMS report were cited in “the naturals” category. Others who made the list of 100 include Vladimir Putin, Pope Francis, the Mars Rover Team, Mark Zuckerberg, Shinzo Abe, and the IPCC. Foreign Policy will be honoring the 100 Global Thinkers at a special event this Wednesday in Washington, D.C.

Watch for the third extreme-events supplement to be released with BAMS next September.