The AMS recently presented outgoing Journal of Climate Chief Editor Andrew Weaver with a plaque to thank him for his volunteer service to the Society. This is the beginning of a new tradition to honor every chief editor when they step down from their position, and it is appropriate that Weaver is the first to be recognized in this way, as during his term (2005-2009) the Journal of Climate grew significantly and earned consistently high ratings for its impact in the field of climatology.

“It just so happens that our recognition of chief editors ending their tenure begins with one of the most successful of all the CE’s,” notes AMS Director of Publications Ken Heideman. “Andrew built on the foundation that others established before him and took it to a new level.”

As Heideman describes it, Weaver’s predecessors as Journal of Climate chief editor–NOAA’s Alan Hecht (1988), the University of Oklahoma’s Peter Lamb (1989-1995), and Colorado State University’s David Randall (1996-2004)–helped to establish the fledgling journal as a leader in climate research. By the time Randall handed the reins to Weaver, it was, according to Heideman, a “hot journal. And then Andrew helped make it one of the hottest journals.”

During Weaver’s tenure, the Journal of Climate page count increased by almost 25%–from 5,400 to 7,000. More importantly, its ISI impact factor reached #1 in the category of meteorology and atmospheric sciences and was never lower than #4. The Journal of Climate has the most submissions and the most published papers of any AMS journal, as well as the most editors and editorial assistants. Weaver’s work sets a high standard for other chief editors.

“It’s amazing how much time Andrew put into the job,” says Heideman. “He routinely handled 100 papers a year by himself, and sometimes more. That was far above what we at AMS expected.”

For his part, Weaver found his time working with AMS “incredibly rewarding” and was especially pleased that he was able to keep up with what was happening in the field of climatology during a such a fertile period. His philosophy for the journal was simple and effective: do a good job in the editorial process, and the authors will come back.

“I’m most proud that the journal’s growth happened in the most tumultuous time in terms of climate politics, and we had no issues with that whatsoever,” he remembers. “Everything we did was just about the peer-reviewed science.”

As an organization led by its members, AMS relies on the volunteer spirit of people like Weaver not only to edit its journals but also to run nearly 100 boards, committees, and commissions.

AMS Gets Energized for Severe Weather

According to a survey last spring, almost seven out of ten Americans expressed little to no concern regarding possible emergency weather situations, and nearly half (43%) said they were unprepared for situations resulting from severe weather, such as power outages. According to the International Association of Fire Chief (IAFC), many people make the mistake of using candles instead of an emergency battery-powered kit in the event of a power outage, resulting in approximately 15,000 home fires annually.

To get this information about weather safety out to the public, AMS has joined the IAFC and Energizer in their weather preparedness initiative as part of the Change Your Clock Change Your Battery campaign. The public education program, Energizer Keep Safe. Keep Going®, which officially kicks off on the first day of spring, provides tips for building a power kit to keep critical lines of communication open.

AMS is encouraging on-air broadcasters to utilize the kits as informative props or possibly as giveaways to viewers. “Energizer sees the broadcast community as the perfect platform to spread this important message because they have the most direct conduit into homes,” says Keith Seitter, Executive Director of AMS. “Everyone turns to them when severe weather is threatening.”

Energizer will also be providing support for the Broadcast Conference in Miami this June, sponsoring travel for some of the severe weather experts and invited speakers and co-sponsoring the short course to enable more broadcasters to participate. “Their sponsorship of the Broadcast Conference is allowing the conference to offer an increased level of professional development for attendees,” comments Seitter. “This in turn benefits the meteorological community and our service to the general public. We’re expecting to have Energizer call on the AMS community for scientific expertise on storm safety and preparedness as this program continues to unfold.”

How Roguish Is a Rogue Wave?

For many travelers, lounging on the deck of a cruise liner with a fruity drink in hand is the ultimate in luxurious relaxation. According to the industry Web site cruisemarketwatch.com, more than 18 million people will vacation on a cruise ship this year. And while those idyllic visions of leisure are usually accurate, two recent disasters have spotlighted the potential hazards that unexpected severe weather can bring to cruise ships.

In early March, the Louis Majesty was cruising the Mediterranean off the coast of Marseille, France, with more than 1,900 people aboard when it was battered by three 30-foot waves. Two people were killed and 14 were injured after the waves broke glass, ripped out furniture, scattered debris, and flooded cabins. Marta de Alfonso, an oceanographer with the Spanish government, told the Associated Press that a powerful storm was influencing Mediterranean at that time, with reports of winds in excess of 100 km/h (60 mph).

Significant wave heights of around 20 feet were recorded by buoys in the area. “Rogue waves” are at least double the significant wave height, so the waves that struck the Louis Majesty are not considered rogue. As CNN’s Brandon Miller explains here, wind and current direction and sea floor topography can all cause abnormally large waves. Nevertheless, De Alfonso said that waves of the size that struck the ship generally appear in the Mediterranean only one or two times a year.

The previous week, the Costa Europa, a cruise liner in the Red Sea carrying almost 1,500 passengers, was docking at the Egyptian port of Sharm el-Sheik when it violently struck a pier, ripping open a six-foot-wide hole in the hull. Three crew members were killed and three passengers and one crew member went to a local hospital with injuries. The cruise line’s CEO blamed “exceptional bad weather conditions and an unexpected gust of wind” for the accident, although a marine official later said the cause was “100 percent human error.”

While it is clear that vacation cruises are generally safe, it isn’t entirely clear how common rogue waves are. Several papers in recent AMS journals have addressed the statistics of waves that stick out from the general sea state around them (for example, Gibson et al. and Janssen and Herbers in Journal of Physical Oceanography), mostly trying to show how it might be possible to for waves to combine and interact to produce exceptional heights only very rarely.

In another paper in the same journal, Johannes Gemmrich and Chris Garrett of the University of British Columbia, make an interesting point about what makes these waves so potentially deadly:

What is clear from many cited examples of what observers describe as “freak” waves is that they tend to be much larger than the waves in the surrounding sea state, often appearing either singly or in small groups, without warning. In many situations, this unexpectedness is more dangerous than the wave height itself, for example, if mariners interpret an interval of several minutes of relatively small waves as an indication of a decreasing sea state.

However they go on to show, in at least one interpretation of their evidence, that the unexpectedness of rogue waves may be in the eye of the beholder.

The frequency with which unexpected waves occur even without the extra possible physics of resonant nonlinear interactions is remarkable and of scientific interest. It suggests that many reported freak waves may not be so freakish after all, but merely the simple consequence of linear superposition. Our predictions could be incorporated into maritime safety manuals or coastal warnings. To be sure, we have based our simulations on deep water scenarios and further analysis is required for nearshore situations, but it seems likely that similar results will emerge. Thus, mariners and tourists can be warned that even a few minutes of waves can be followed by a wave at least twice as high, with such an event likely every few days.

Rarely fatal, the statistics of surprise are nonetheless consistently…well… surprising.

Nothing Will Stop Her from Being a Meteorologist

AMS President Peggy LeMone wrote a guest editorial in the UCAR Staff Notes in January, telling stories from the front lines of the struggle to give women equal footing in the sciences. Interestingly, several times during LeMone’s career at NCAR, women had to formally organize themselves to fight a particularly galling decision or simply to understand and improve their working conditions. None of these episodes, however, quite encapsulates the lonely, embattled situation of women meteorologists during the 1960s and ’70s more than LeMone’s observation that,

When I met Joanne Simpson, she greeted me like a long-lost sister—it was so exciting to meet another woman in the field!”

This little cameo just confirms that no history of women in science (this being, after all, National Women’s History Month) could be adequate without at least some mention of Joanne Simpson, the first woman Ph.D. meteorologist, whose distinguished research career brought her in contact with her female peers all over the country. She was the pioneer who made all the other pioneers possible.

While one would scarcely know it upon meeting and talking to Joanne, the weight of this responsibility blazing a path for her female colleagues took a toll. She said

I have always felt that I’ve been carrying a big burden for other women, because if I mess up then the chances for other women to get the same kind of job are going to be diminished.

Of course Joanne Simpson, who died early Thursday less than three weeks before her 87th birthday, did not mess up. She has long been a legendary pioneer of meteorology. Winner of the AMS Rossby Award (and our president, in 1989) as well as the IMO Prize, she turned meteorology on its head with the discovery that energetic processes in clouds don’t just signify the atmospheric circulation, they help drive it. She went on to extend her concept of “hot tower” clouds to explain the inner workings of the heat engine of hurricanes, then fought for the satellite observing systems that would later show such clouds in action.

Simpson basically created from scratch the discipline of cloud studies as we know it today, then mentored the people and fostered the technology to make sure it would thrive. (For more of Simpson’s inspiring story, be sure to read John Weier’s biographical article at NASA’s Web site, or the AMS monograph, Cloud Systems, Hurricanes, and the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission, A Tribute to Dr. Joanne Simpson.)

It was quite obvious to the multitudes who knew Simpson that she was in this science for the love of the science itself; consider what she told LeMone in a 1989 interview:

My greatest wish would be to be like Grady Norton, who died of a heart attack while forecasting a hurricane, or like my early hero, Rossby, who keeled over and died in the middle of giving a seminar. I don’t like the idea of when I won’t be a Meteorologist anymore. It’s just inconceivable to me.

Inconceivable indeed, with thousands of people following her path, studying the observations she made possible, using the ideas she formulated. Nothing could ever stop Joanne Simpson from being a meteorologist. Not then, not now.

No real story of meteorology could be written without telling hers. We invite you to do exactly that and share your own part of her story in the comments section.

To Don Kent, the Meteorology Was What Mattered

Guest Post by Bob Henson, UCAR

I consider myself forever lucky to have met Don Kent. On a bright, mild afternoon last September, I drove to New Hampshire with AMS archivist Jinny Nathans and NCAR archivist Kate Legg to interview Don for the AMS-UCAR oral history project. Knowing that I was at work on a history of television weathercasting (Weather on the Air, to be published this June by AMS), Jinny suggested the time was ripe to get the full interview that Don and his illustrious career so richly deserved.

We spent a delightful afternoon as Don recounted the saga of his involvement in weather and broadcasting. It began during his 1920s boyhood, listening on the radio to Boston’s original weathercaster, E.B. Rideout. There were obstacles along the way, including the ones Don hurdled as a volunteer weatherman for WMEX in the late 1930s, not long after high school. As was the case until the 1950s, radio stations couldn’t even get teletype reports, much less Internet feeds, so Don had to traipse back and forth each day:

“I went to the weather bureau at Boston at 11 a.m., got the first map off the press at 11:30, and got up to the radio station for the 12:55 broadcast.”

Don told us about experiencing and covering the great hurricanes of 1938 and the 1950s. He recounted his adventures and achievements during World War II and his serendipitous return to weathercasting years later. His eyes brightened as he recalled his defense of on-air meteorology during the 1960s, when a WBZ news director told him either Kent or the isobars on his maps would have to go. (In the end, of course, they both stayed.)

Interestingly, this legendary weathercaster and self-proclaimed “weather nut” told us that, of late, he’d been turning to the Internet rather than television for his atmospheric fix. Who needed TV, he said, “when you’ve got your own computer showing the satellite and all the other stuff.”

What mattered most to Don, it seemed, wasn’t the medium but the meteorology. His legacy is safe among the thousands of Bostonians who counted on his dependable, no-nonsense reports, as well as the many weather communicators he mentored and inspired. If he’d had a youth serum handy, I have no doubt that Don would be podcasting, blogging, and YouTube-ing for decades to come. Guest Post by Bob Henson, UCAR Communications Office.

Urbanization: Paving the Way for Floods

The Portuguese archipelago of Madeira, nestled in the Atlantic Ocean off the coasts of Portugal and northern Africa, is normally a subtropical island paradise. But severe flooding on the island last weekend created a disaster that killed dozens and has local environmental leaders blaming the urban planning in the region as much as recent heavy rainfall. They believe that extensive development on the island of about 250,000 people over the last few decades created conditions that exacerbated the severe weather that struck over the weekend, when more than 11 cm of rain per fell in 5 hours in the town of Funchal–more than 15% of what it normally receives in an entire year.

“The situation has gradually been aggravated due to land-use zoning problems and errors committed on the island,” said Hélder Spínola of Quercus, a Portuguese environmental organization. These “errors” include the development and paving of land along the coast and near waterways and disruption of the flow of Madeira’s three largest rivers. During the recent storm, the rivers overflowed, storm runoff did not effectively drain into the ground, and much of the water was forced into drainage channels that were unable to hold the tremendous amounts of rain. As a result, raging rivers of mud and debris stormed down the hillsides, plowing through roads, buildings, bridges, and anything else in their path. Adding to the problem was the absence of a weather radar in Madeira, which prevented an accurate forecast of the unusually strong storm.

While local government officials denied that faulty planning and overdevelopment were to blame for the catastrophe, research has long shown that urbanization increases frequency of flooding. For example, an upcoming article by Yang et al. in the Journal of Hydrometeorology finds that when the impervious surfaces cover more than a mere 3-5% of the total area in a watershed, there is a statistically significant effect on streamflow.

The Rules of Removal

Like everything in life, snow removal has its rules and someone is always going to be unhappy with them. This is particularly true in places with relatively mild winters that occasionally get walloped, like Washington, D.C. this February.

What happens after the snow stops falling and residents and business owners are left with the job of clearing parking spots and sidewalks? What rules do they follow? In Boston, a city law states that by digging your car out in a snow emergency, the spot can then be claimed for two days by “saving” it with a lawn chair or trash can. In Chicago, this is illegal. In D.C., residents were left wondering.

“I know this is public property, but if you spent hours laboring, I mean, come on, I think you have the right to say that is my spot,” Tanya Barbour told the Washington Post after spending two hours shoveling her car out.

The sidewalk etiquette question is not much clearer. In portions of Maryland, business operators and multifamily homeowners have 24 hours after the snow ends to clean off sidewalks, or face a $50 fine; in Prince George’s County, owners get 48 hours before they can be fined $100. Much of Virginia does not issue penalties for not shoveling, but rather encourages residents and business owners to do so to help neighbors and keep customers safe.

One sidewalk angel quoted in the Washington Post, however, turned snow clearing into a philosophical question:

Steven Williams…noted that some people wait until the snow melts to make shoveling easier. “When is too early or too late to do anything in life?” he asked. “Who makes the rules?”

[We’re tempted to turn that into a meteorological question: If you wait until some of the snow melts, doesn’t that make it likely your shovel loads will be a lot heavier than if you’d cleared the freshly fallen flakes? Can one use the meteorological variables to calculate an index of procrastination due to precipitation?]

In the meantime, the most important rule of snow etiquette seems to be that enumerated by the Arlington, Virginia, blog, “Shirlington Circle” in their list of “snow paux”:

5. Build snow sculptures. DC sees so few inches per year…so try attempting a piece of architecture or a family-friendly snowperson. It also shows a neighborhood that plays together stays together.

Now, how to extend the etiquette of snow to martial arts of blizzards? The Official Dupont Circle Snowball Fight Fan Page on Facebook reached 5,000 members in anticipation of their scheduled February 6 battle in downtown D.C. The local media estimated the turnout at 2,000. That’s a great way to settle disputes over parking spots.

"Carbon Copy" Satellite Budgeted

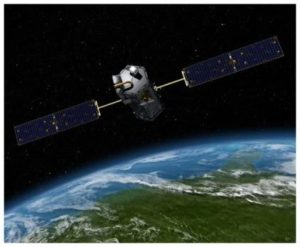

Last year, NASA’s Orbiting Carbon Observatory left climate scientists disappointed when it failed before it even  began. The $278 million satellite plunged into the Indian Ocean near Antarctica in February 2009 after a fairing on the probe’s Taurus XL rocket didn’t separate during launch. Now, the science community is hoping the sequel, OCO-2, will deliver what the first could not: measurements accurate enough to show for the first time the geographic distribution of carbon dioxide sources and sinks on a regional scale.

began. The $278 million satellite plunged into the Indian Ocean near Antarctica in February 2009 after a fairing on the probe’s Taurus XL rocket didn’t separate during launch. Now, the science community is hoping the sequel, OCO-2, will deliver what the first could not: measurements accurate enough to show for the first time the geographic distribution of carbon dioxide sources and sinks on a regional scale.

OCO principal investigator David Crisp of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and his team evaluated the possibilities of getting another satellite up in space and chose to try again with the same design. “This is a carbon copy of the original,” Crisp comments, “with just a few minor, now-obsolete parts replaced.” Within three days after the failed launch, the OCO science team created a proposal for an OCO-2.

A year ensued, but as part of the 2011 Earth and Climate Science Budget released this month, the White House has now slotted $170 million for NASA to develop and fly OCO-2.

The new satellite is scheduled to be rebuilt and launched in 28 months, after 1 October of this year, when the budget would take effect if approved.

OCO isn’t the only mission to benefit in the Obama Administration’s proposed 2011 budget. Existing missions such as the Global Precipitation Measurement and the Landsat Data Continuity Mission will receive a monetary boost as well as several planned missions, such as the Glory mission, the NPOESS Preparatory Project mission, and the Aquarius mission.

Climate scientist Ken Caldeira of Stanford University was happy with the news of OCO returning to space. “The Orbiting Carbon Observatory is a key piece [of] the monitoring system that we need to keep track of our changing Earth, so that we might better understand the complex interplay of Earth’s climate system and carbon cycle, and therefore help to better inform the difficult climate-related decisions that we will need to make over the coming years and decades.”

Olympic-Sized Fear: No Snow

The Vancouver Winter Olympics begin on Friday with the first-ever opening ceremonies held indoors. That decision seems prescient on the part of the organizers, given that Friday’s forecast is calling for rain, and some Olympic officials may be starting to wish they had scheduled the entire games to be conducted under controlled conditions. According to Environment Canada’s Mike McDonald, one of 30 meteorologists working at the Games, Vancouver’s average temperature of 7.19°C (44.9°F) in January was the highest ever recorded for that month and about 3°C warmer than the normal average. The unusual warmth has continued into February and caused a paucity of snow at some venues–particularly at Cypress Mountain, the site of the freestyle skiing and snowboarding events (moguls, aerials, ski cross, half-pipe, snowboard cross, and parallel giant slalom).

The situation is so extreme that snow is continuously being shipped from other local mountains to Cypress by both truck and helicopter to ensure there is enough for competition.

In addition to importing the snow, tubes filled with dry ice have been scattered across the mountain in a never-before-used technique that distributes cold air across the snow to help preserve it.

The weather conditions have many pointing to global warming and wondering if the number of potential host sites for the Winter Games may continue to decrease due to the spread of warmer weather. But as the University of Washington’s Cliff Mass explains in his blog, most meteorologists in the Vancouver region have an alternate suspect:

The problem, of course is El Niño. . . . As I have explained before El Niños are associated with above normal temperatures and below normal precip after January 1. And substantially lower than normal spring snowpacks. Now, lets be careful…this is a correlation, not an exact prediction. El Niño winters tend to have less snow, but some have had more than normal. Now the problem we have is that we are starting the El Niño season with a below normal snowpack. . . . Lots of the NW is 65-80% of normal.

The rising sea surface temperatures in the tropical Pacific that indicate an El Niño event were originally identified last summer, and what Mass calls a “moderate” El Niño has persisted through the winter and is expected to continue for months. Additionally, a flow of warm, moist air originating from around Hawaii known as the “pineapple express” could also be playing a part in the unusual warmth in the Pacific Northwest. And those blaming global warming should note that the Olympics have dealt with problems like these before, most notable in Innsbruck, Austria, in 1964, when a shortage of snow caused by a mild winter forced the Austrian army to carve out 20,000 bricks of ice to be used on the luge and bobsled runs, and also transport 40,000 cubic meters of snow to ski slopes, packing it down by hand.

With the additional snow arriving from other mountains, officials believe that the games will go on without a hitch, with Tim Gayda, vice president of sport for the Vancouver Olympic Organizing Committee, recently stating: “I am 100% confident that the events will take place and we’ll have enough snow to get the job done.”

This Day's for You

Paul Piorek, weathercaster for the local cable service News 12 in Connecticut, leads a busy life working a demanding shift schedule familiar to many meteorologists:

I wake up at 2 o’clock every morning, and I’m generally in the office by 3:05. People always ask me why I arrive so early if we don’t go on the air until 5:30. Believe me, it takes at least two hours to pour over the meteorological data, create customized graphics, provide local radio stations with recorded forecasts, write a weather discussion for the News 12 Connecticut Web site, begin working on a blog entry, and type the forecast for the info bar on the bottom of the screen. Despite what many people think, I just can’t “look out the window.”

The results don’t always bring accolades:

Although I’ve never been an umpire or referee, I think I know what it must feel like. It’s been said that nobody ever notices the umpire when he does a fine job. However, when the ump makes a bad call, everybody’s on his back. You see, I have been forecasting the weather for southwestern Connecticut on television and radio over the last 20-plus years. I never hear a word from anybody when the forecast is “right on the money.” But, if my forecast is off the mark, the phone doesn’t stop ringing and the emails keep coming.

But don’t feel sorry for Paul, because unlike so many other unsung heroes in life, he does it, like so many, because he loves the weather.

For me, though, it’s a labor of love. I often tell people, when you love what you do, you’ll never work a day in your life. Happy National Weatherperson’s Day!

What’s that? Oh yes, unlike so many unsung heroes in daily life, weather people get a day to celebrate being who we want to be. And it’s today because this is supposedly the birthday of John Jeffries, the Boston physician who was one of the first American weather enthusiasts of note; just in time for the American Revolution, before the age of storm chasing and broadcasting, he began 40 years of meticulous observing and indulged a daring penchant for ballooning to satisfy his hankering.

All in all it’s not bad to be into weather. Have a nice February 5th, whatever you call it, but keep your feet on the ground.