Predicting–as opposed to actually voting in–elections has become a national  past-time, if one is to judge the media’s obsession with who’s going to win what in today’s midterm contests in the United States. And what better way to make predictions than to ponder the weather map?

past-time, if one is to judge the media’s obsession with who’s going to win what in today’s midterm contests in the United States. And what better way to make predictions than to ponder the weather map?

Tony Wood of the Philadelphia Inquirer, however, disputes the oft-cited connection between weather and election results. In a post last week on “Weather, Democracy, and Mythology“, he looked into the old theory that rain dampens voter turnout and concluded that it doesn’t hold water:

Consider the 2004 presidential election. Recall that it all came down to Ohio in a close race between President Bush and Democratic nominee John Kerry.

That Election Day was a nasty one all over the state. It rained almost everywhere. The result? The voter turnout in Ohio was believed to be highest in at least 40 years. Some folks were said to be waiting up to nine hours to vote.

We did our own analysis of 30 years of election returns and weather in Philadelphia found no evidence of a link between the two. It rained on half of the Election Days with the 10 highest turnouts, while seven of the 10 lowest-turnout days were rain-free.

What about the oft-told story of the 1960 election? In his classic, The Weather Factor, meteorological historian David M. Ludlum claimed that rain in Illinois (on an otherwise mostly fair day across the country) hindered Nixonian rural voters more than Kennedy liberals in Chicago? Wood counters with political analyst Terry Madonna of Franklin & Marshall University, who says weather took a back seat to the behind-the-scenes intervention of Mayor Richard Daley:

“It [the rain] didn’t matter,” said Madonna, “because Daley had those votes already counted.”

We’re not sure how that explanation is logical (given that Ludlum’s theory is more about the lack of rural voters than about any surge in urban voters), but more specifically it would be great to see more of Wood’s 30-year study. In the meantime, the one recent study, by political scientist Brad Gomez and colleagues, quantifies a correlation between weather and voter turnout. The paper, published in 2007 by the Journal of Politics, was discussed at the 2008 AMS Broadcast Meteorology conference (audiovisual version here) by Allan Eustis.

Gomez et al. found that every inch of rain above normal correlates significantly 1% reduction in voter turnout. Similarly, every inch of snow correlates significantly to a 0.5% drop in voter turnout.

Eustis pointed out some limitations in this seemingly exhaustive study involving 22,000 weather observations (to resolve weather effects locally) across 14 national presidential elections. For instance, there’s no mention of extreme temperatures or windy weather. Eustis believes extreme weather, not deviations from norms, are more significant in turnout (therefore a linear relationship between precipitation and voting might not be valid).

Cliff Mass of the University of Washington discusses the Gomez paper in his blog and quickly throws a bucket of cold water on the the relevance of those numbers for today’s election, anyway:

Now an inch of rain is quite a bit of precipitation, only occurring during major storms (like Monday in the NW) or in thunderstorm areas.

Furthermore, these results were for presidential elections where people are generally highly engaged and motivated. What about midterm elections like Tuesday’s? If we assume that people would be less excited than for presidential runs would one expect the influence of precipitation to be greater for this election?

And what about the influence of the greater proportion of absentee ballots and of extended balloting times (some places in the U.S. allow voting in the weeks before the election)?

Playing along with the Gomez et al. paper for the moment, however, Mass predicted (on Sunday) that if Republicans are indeed favored by lower turnout and thus precipitation, the relatively small areas of rain today will have little impact because it will fall areas that are already leaning heavily toward Republicans.

Eustis, however, notes that other studies of weather and elections, unlike Gomez et al., don’t support the adage that Republicans pray for rain (for instance this 1994 paper by Steve Knack of American University).

What Eustis has learned while working for the National Institutes of Standard and Technology, however, is that the weather effects the voting systems, not the voting people: apparently optical scanners can incorrectly process paper ballots, which expand in excessive humidity causing misalignment (see the 2005 SAT scoring controversy).

Ah, for the simple days when gentleman farmers slogged through the mud and rain, got further sloshed with liquor, shouted their preferences to the poll takers, and went home waiting weeks for the results with nary a prognosticating pundit to second-guess them.

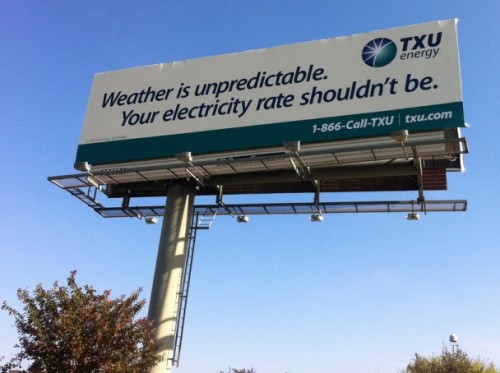

Broadcast meteorologist Kevin Selle posted this picture to his blog, Digital Meteorologist, with the spot-on comment: “Note to self. Switch energy providers.”

Broadcast meteorologist Kevin Selle posted this picture to his blog, Digital Meteorologist, with the spot-on comment: “Note to self. Switch energy providers.”