If ever there was a day meteorologists might like to do over, it was exactly 20 years ago today, on 28 August 1990. Somehow, on an afternoon originally projected to have a mere moderate risk of severe weather, an F-5 tornado—the only such powerful tornado in August in U.S. history—struck northern Illinois, killing 29 people in the small town of Plainfield, just 30 miles southwest of Chicago.

The sky turned black, and few people knew what happened as the rain-wrapped tornado ripped through the landscape. Almost no one saw the funnel. (Paul Sirvatka, just then starting up his College of DuPage storm chasing program was a rare exception.) Even though another tornado was spotted earlier in the afternoon in northern Illinois, no sirens wailed in Plainfield until too late. No tornado warnings were issued until too late.

Tom Skilling (WGNE-TV) broadcast a report this week for the 20th anniversary of the tragic tornado, explaining why warnings would likely be much better should similar weather now threaten the Chicago area.

The gist of the story: back in 1990 Chicagoland didn’t have NEXRAD Doppler radar and other recent advances in observing and modeling. Also, the aftermath led to a reorganization of the overworked Weather Service meteorologists in Illinois, narrowing the purview of the Chicago office and adding more offices to help cover the state.

While most stories in the media (for example, also here) have been showing why 20 years have made a repeat of Plainfield’s helplessness less likely, Gino Izzo of the NWS Chicago office decided to have a do-over anyway–on the computer. At his presentation for the AMS Conference on Broadcast Meteorology in June, Izzo described how he reran the severe weather forecasts for 28 August 1990 using the North American Regional Reanalysis and the most up-to-date model of 2010, the Weather Research & Forecast model (WRF) from UCAR.

With a nested 4 km grid at its most detailed, Izzo ran the WRF overnight–it took 10 hours on the available computer in the office–and found that in fact, with the observational limits of 1990, the latest, greatest numerical forecasting doesn’t really improve the severe weather outlooks for the Plainfield disaster. The WRF moved the likely areas of severe weather (not tornadoes necessarily, but probably winds associated with a bow echo) too far eastward. Only when the model time horizon was getting within a few hours of the killer tornado did the severe weather outlook for northern Illinois start to look moderate, as the model begins to slow down the eastward progress of the cold front.

Audio and slides from Izzo’s striking presentation are available on the AMS meeting archive. The message is pretty clear: no matter how good the models get, Doppler radar, wind profilers, aircraft-based soundings, and satellites make a huge difference in our severe weather safety these days.

Of course, with or without better warnings, a repeat of the Plainfield disaster would be potentially catastrophic. The area has more than doubled its population since 1990. And 28 August just happened to be one day before school resumed for the fall—few people were at the high school that was totally destroyed that day. Even just a day’s difference, let alone two decades, could have been critical. Nobody wants a do-over.

Weather Systems

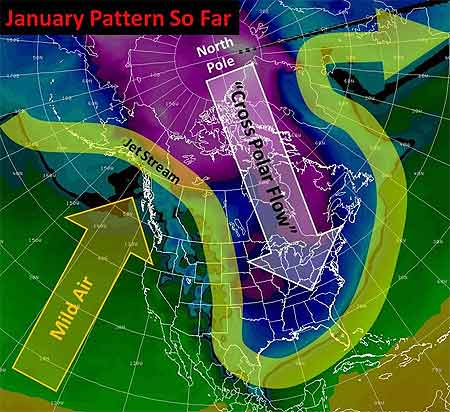

Harsh Cold Wave Slowly Retreating

Well, the big winter cold snap that has been gripping much of the United States since December is nearing its end. Temperatures in most places from the Plains to the East Coast have started to rebound and no renewed surges of Arctic air are on the horizon after a final weak front moves through the East Tuesday. But the damage is done in places from the Dakotas and Montana to Florida: burst pipes, roads that drifted shut, and wind chills lower than -50 in the North, and car crashes on icy roads, power outages, and record cold that has chilled the South.

Last Thursday, the wind chill in Bowbells, North Dakota hit 52° F below zero. That degree of cold “freezes your nostrils, your eyes water, and your chest burns from breathing — and that’s just going from the house to your vehicle,” said Jane Tetrault of Burke County. Her vehicle started, but the tires were frozen. “It was bump, bump, bump all the way to work with the flat spots on my tires,” she said, adding, “It was a pretty rough ride.”

Snow and icy winds whipped southward from the Midwest into Tennessee, Georgia, and Alabama late in the week, making travel a disaster in Memphis and Atlanta. Video of cars sliding off roads or into each other played every half hour on The Weather Channel into the weekend.

Even the Sunshine State had wintry precipitation with this unusual cold surge—something not seen in more than 30 years. The weekend into Monday was especially brutal by Florida standards. With temperatures in the 30s and low 40s, light rain enveloped the peninsula Friday night through Saturday. Sleet fell in spots from Jacksonville and Ocala southward through Orlando, Tampa, and Melbourne into Palm Beach. A few wet snowflakes mixed in here and there with snow reported by trained spotters as far south as Kendall, a southern suburb of Miami. In some places north of Tampa, enough sleet accumulated on cars and outdoor furniture to build little “sleet” men, complete with tiny hats and tree-twig arms, their photos rivaling those taken of snowmen built in Tampa on January 17, 1977. (View a of Florida sleet from a snow and ice slideshow on Tampa’s baynews9.com.)

Clearing led to record morning lows both Sunday and Monday that threatened harm to Florida’s $3 billion citrus industry. Temperatures bottomed out at 25° in Tampa, 29° in Orlando, and 31° in Ft. Myers. On Sunday, the temperature in Miami tied the 1970 record for the date with 35°, and a 36° low Monday morning broke the previous record for the date of 37° set in 1927. Despite the records, it has been the duration of the cold, especially in the South, that makes this cold snap memorable. Morning after morning since the previous weekend, photos of Florida strawberries encased in ice showed up on newscasts. Such protective measures against the frigid temperatures are expected for several more mornings in central Florida, even as the chill slowly moderates.

The cold was even long-lasting in the Midwest and Plains, as noted in TWC meteorologist Tim Ballisty’s article “It’s Cold But So What?” last week. He points out that Chicago hasn’t been above freezing since Christmas Day, at the time 11 straight days and counting. Cleveland had 10 consecutive days of snow, and that count continued right into the weekend.

Unlike the extensive heat waves of recent summers, this long and harsh cold snap resulted in relatively few new temperature records. At the Annual Meeting in Atlanta, Gerry Meehl of NCAR will explore the rising ratio of record high temperatures to record low temperatures, which is expected to markedly increase by the middle of the century with current projections of climate warming.