by William Hooke, AMS Policy Program Director

A post from the AMS project, Living on the Real World

Back in the 1990s, while still working at NOAA, I was once part of a two-day U.S.-Japan bilateral discussion in Tokyo on science and technology issues. Bill Clinton was President. Walter Mondale, Jimmy Carter’s former Vice President, was then ambassador to Japan. Tim Wirth, who at that time was Under Secretary of State for Global Affairs, was leading this particular delegation. Wirth, Mondale and the rest of us from the U.S. side were in a big meeting room with the Japanese. Leaders from Japanese government and industry filled the room, under auspices of MITI, the Japanese Ministry for International Trade and Industry. The Japanese couldn’t comprehend why the United States was moving so haltingly on a range of environmental and hazards matters.

“You have to understand,” Tim Wirth was saying, “that if government and industry worked with each other in the U.S. the way you do in Japan, people would go to jail.”

Tim Wirth’s remark has everything to do with this week’s discussions at the AMS Summer Community Meeting in State College. Two points: First, and foremost, this is our history and our policy in America. Our nation decided long ago that we wanted a free-market society, with minimal government. We wanted government to focus primarily on regulations that would foster capitalism and business competition, and at the same time curb corruption, restraint of trade, monopolistic practices, and other abuses. Second, this approach is a policy, a choice, or framework of choices, not an inescapable reality. Other governments are free to adopt other approaches, and have, as the Japanese example illustrates.

Well, as is so often the case, you pick your poison. The Japanese approach spurred

Uncategorized

Civil War Sleuthing

Historians have long known—thanks to diaries and other first-person accounts—that weather played a small but possibly significant role in the Battle of Wilson’s Creek, August 10, 1861. This was the first important engagement of Union and Confederate forces west of the Mississippi River and was pivotal in determining the political alignment of Missouri early in the Civil War.

On the evening of August 9th the Confederate leader, General McCulloch, had decided to march on the nearby Union force, but rainfall starting around 9 p.m. convinced him to abandon the plan until morning, and to stay at camp to keep munitions dry. The rain delay enabled the smaller Union force, under Brigadier Nathaniel Lyon to creep up on Confederate encampment at dawn the next morning for a surprise attack.

All in all, the Confederates were able to rally themselves and ultimately force Union troops to back away—both sides suffering over a thousand casualties in the process. The Confederates parlayed their victory at Wilson’s Creek into control of a substantial portion of Missouri in the initial part of the war.

What historians lacked, however, was a good explanation of the weather situation that affected strategy in 1861. No weather stations were reporting from the area. Now, thanks to the enterprising research into analog synoptic maps, Mike Madden and Tony Lupo of the University of Missouri may have given students of the Civil War a credible meteorologist’s look at that fateful day in August 1861. For more on how Madden and Lupo did it, see the article by Randy Mertens in the Ozarks nature and science website, Freshare.net.

From Parallel Play to True Collaboration

by William Hooke, AMS Policy Program Director

A post from the AMS project, Living on the Real World

A few years ago, my daughter, who is a social worker, introduced me to a new term (at least new to me). We were watching my grandchildren (her children and their two cousins) sitting on a floor ankle deep in toys. There was occasional noise. I said something about how they were all doing together, and she laughed and said, “Oh, Dad, that’s only parallel play. Just give them a couple more years.” What she meant was, they were occupying the same space, but they were really engaged in toddler’s solitaire, focused on a few toys and oblivious to the others around them, except when possession of a toy would come into dispute.

Her forecast verified. Today, the oldest is only eight, but already when those same kids are together, the engagement is on an entirely different plane. There’s talk, there’s laughter. There’s common purpose and shared energy. They’re cooking up projects. It’s amazing. I can hardly wait until we hit the next level.

Something like that is happening in meteorology. Back in the postwar world of the late 1940’s (see Billionaires follow lead of former private-sector meteorologist), Lewis Cullman and his fellow private-sector meteorologists were sharing the same space with the Weather Bureau, and frustrated by what they saw as unfair competition in the service delivery. It was only this one aspect that concerned them. Everyone conceded that the government would be responsible for the observations, for the communication and compiling of all that information. Numerical modeling still lay a few years in the future. The issue was who would deliver the paltry weather information of the time that last mile to the public, and to specialized users.

Fast forward sixty years. Today public and private sector are partnering up across every link in the chain from weather observations to use of that information to save lives, grow the economy, protect the environment, and foster national security. The government still owns many of the observing instruments and platforms. But the radars, the satellite sensors, the satellite platforms themselves, the data links, and the big computing facilities are all built by the private sector. And when it comes to surface sensor networks, federal government agencies today own only a small fraction of the sensors. The rest are in multiple hands. Go into any government computing centers, where the big numerical weather predictions models are being run, and it won’t be uncommon to find contractors working side by side with government employees, in operations and maintenance, doing model development, etc. Virtually all of the service delivery is in private hands – and a wide range of those to boot. What once was the purview of the daily newspapers, radio stations, is now everywhere – on the internet, on laptops, handhelds, in cars – you name it. And at every step, it’s hard, and in some sense, rather pointless, for users to separate out the respective roles of public- and private-sector players in bringing this information to them.

And this collaboration is facing complex new challenges. Let’s look at just one – wind energy. Every evening, when you and I are watching television, we see advertisements touting green energy, and more likely than not, showing a farm of wind turbines, majestically towering above the terrain, and turning slowly in the background. But there’s a complicated reality behind all this.

The towers are now 100 meters high (think of a football field turned upwards on its end). Wind speeds are variable from top to bottom of the turbine blades. In fact the blades are now so big that wind direction can be substantially different between top and bottom of the blades. The resulting stresses increase the need for maintenance, and reduce the turbine lifetimes. Don’t believe me? Go to Google Images, and type in “wind turbine damage.” You’ll see pictures of turbines missing blades, of blades so warped they look like something from a Salvador Dali painting, of turbines on fire, of burnt-out turbine hulks. At the same time, the complexities of temporally-variable low-level winds over the irregular terrain where we find many of these wind farms mean power output is less than what may have been hoped.

One of the keys to reducing the need for turbine maintenance, and increasing the power output from wind farms is better numerical weather prediction, not on global scales, but on the scale of the wind farms themselves, and for just a few hours. Turns out that such forecast capabilities have other uses as well – for solar power, or for agriculture, or to support ground transportation. So what should we do? And who should do it? And how will we pay for it? To tackle these issues requires that government, corporations, and academic researchers all pull together. The conversations here at State College are partly about sorting all that out, on strategic as well as tactical levels.

Today, here in State College, as the private sector, the public sector, and academic researchers convene, we’re only eight years old in weather,-water,-and-climate-services-and-sciences years. Our field is still young. But there’s talk, there’s laughter. There’s common purpose and shared energy. We’re cooking up projects. It’s amazing. I can hardly wait until we hit the next level.

For more posts by William Hooke, visit his AMS blog, Living on the Real World.

Weathercasters in Multiple Exposures

A recent blog post by Bob Henson, author of the new AMS book, Weather on the Air, serves as a good summary of the growing news coverage of broadcast meteorologists’ take on global warming. Much of this coverage stems from a recent survey of weathercasters released by George Mason University, in which, as Henson notes:

…the most incendiary finding was that 26% of the 500-plus weathercasters surveyed agreed with the claim that “global warming is a scam,” a meme supported by Senator James Inhofe and San Diego weathercaster John Coleman. On the other hand, only about 15% of TV news directors agreed with the “scam” claim in another recent survey by Maibach and colleagues. And Maibach himself stresses the glass-half-full finding that most weathercasters are interested in climate change and want to learn more.

Henson cites The New York Times, National Public Radio, ABC’s Nightline, and Comedy Central’s The Colbert Report as some of those that have examined the issue recently. The most recent “exposé” was a 10-minute segment entitled “Weather Wars,” on Australian “Dateline”; it features a number of AMS members.

Cool Roofs Seen in Black, White, and Green

Science teaches us not to answer questions in black and white terms—the meaning of data usually has many shades of gray. So it is with figuring out the micro and macro effects that different roof coverings might have on global warming or energy efficiency. The answers are starting to look more complex, and more promising, than ever.

For example, it would seem natural when studying rooftops and their effects on climate large and small to focus on extremes of albedo—in other words, black and white surfaces. This is sometimes the case in simplified modeling studies. But at this week’s AMS 9th Symposium on Urban Environment, in Keystone, Colorado, Adam Scherba of Portland State University submitted findings that moved beyond simple comparisons of white (“cool”) roofs versus black roof coverings. He and his colleagues mixed roof coverings, notably photovoltaic panels and greenery (which has the advantage of staying cooler during the day but not, like white roofs, getting much colder at night). The mix makes sense when you consider that roofs are also prime territory for harvesting solar energy. Scherba et al. write that

While addition of photovoltaic panels above a roof provides an obvious energy generation benefit, it is important to note that such systems – whether integrated into the building envelope, or mounted above the roof – can also result in an increase of convective heat flux into the urban environment. Our analysis shows that integration of green roofs with photovoltaic panels can partially offset this undesirable side effect, while producing additional benefits.

This neither-black-nor-white-nor-all-green approach to dealing with surface radiation makes sense from both energy and climate warming perspectives, especially given the low sun angles, cold nights, and snow cover in some climates. For instance, a recent paper, in Environmental Research Letters, uses global atmospheric modeling to estimate that boosting albedo by only 0.25 on roofs worldwide—in other words, not a fully “cool” scenario of all white (albedo: 1.0) roofs—can offset about a year’s worth of global carbon emissions.

And the authors of a recent modeling study (combining global and urban canyon simulation) published in Geophysical Research Letters simulated a world with all-white roofs but showed that:

Global space heating increased more than air conditioning decreased, suggesting that end-use energy costs must be considered in evaluating the benefits of white roofs.

Delving directly into such costs this week at the AMS meeting is a paper from a team led by Anthony Dominguez of the University of California-San Diego. They looked at the effects of photovoltaic panels on the energy needs in the structure below the roof, not the atmosphere above it.

Did they find that a building is easier to keep comfortable when covered by solar panels? Well, if you need to air-condition during the day, yes. If, however, like many people on the East Coast this summer, you need to keep cooling at night, then no. This is science—don’t expect a black-and-white answer.

Remaking Stable Boundary Layer Research, From the Ground Up

A recently accepted essay for the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society by Joe Fernando and Jeff Weil is good background reading for this week’s AMS 19th Symposium on Boundary Layers and Turbulence in Keystone, Colorado.

Fernando and Weil point out that research into the lowest layer of the atmosphere where we all live and breathe will need to evolve to meet needs in numerical weather prediction. While progress is apparent in the modeling of the boundary layer when it is stirred into convection, those models have obvious shortcomings when the low-level air is not buoyant—the stable boundary layer typically encountered at nighttime. The stable boundary layer controls transport of pollution, formation of fog and nocturnal jets in the critical time before the atmosphere “wakes up” in daytime heating. Weil, in his presentation this Thursday at Keystone calls the still-flawed modeling of the stable situation “one of the more outstanding challenges of planetary boundary layer research.”

Fernando and Weil write in BAMS that study of the stable boundary needs to be retooled to embrace interactions of relevant processes from a variety of scales of motion. The weakness and multiplicity of relevant stable boundary processes means that investigations of individual factors will not be fruitful enough to improve numerical prediction. Scientists need to temper their natural tendencies to try to isolate phenomena in their field studies and modeling and instead seek

simultaneous observations over a range of scales, quantifying heat, momentum, and mass flux contributions of myriad processes to augment the typical study of a single scale or phenomenon (or a few) in isolation. Existing practices, which involves painstakingly identifying dominant processes from data, need to be shifted toward aggregating the effects of multiple phenomena. We anticipate development of high fidelity predictive models that largely rely on accurate specification of fluxes (in terms of eddy diffusivities) through computational grid boxes, whereas extant practice is to use phenomenological models that draw upon simplified analytical theories and observations and largely ignore cumulative effects/errors of some processes.

This new perspective, the authors argue, will be a “paradigm shift” in research and modeling.

Time to Tone Down Hurricane Season Prognostications?

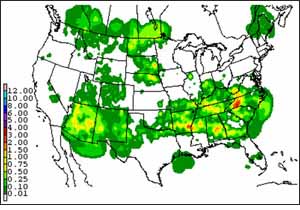

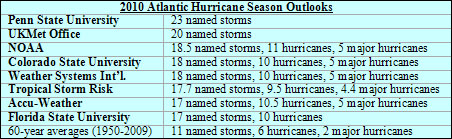

With a third of the Atlantic hurricane season over and just three storms named (albeit accompanied by one tropical depression), should hurricane season prognosticators consider backing down from their early season forecasts of a wild season? And we’re not just talking about one or two Punxatawny Phils here — this year realized eight separate forecasts of named storms and hurricanes for the six-month season, which began June 1. Predictions of the number of named storms ranged from 17 to a lofty 23 — far above the average of 11 named storms realized over the last 60 years.

The real meat of hurricane season is from mid August through mid October, when about 90% of a season’s storms form. Based on the May and June forecasts, that would equate to about 15-21 tropical storms and hurricanes — still a substantially busy season. But the chatter has begun on the blogs (2nd topic on this page) and in the online and mainstream news that this year will not be like 2005. By this point in that season the Atlantic had already seen eight named storms, including two major hurricanes. The 2005 season went on to realize 27 named storms, including Category 5 Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, and Wilma, and one unnamed storm added to the tally in the post-season.

So what drove the early season forecasts? And why might they need to be lowered? As in 2005, sea surface temperatures (SSTs) across the Atlantic basin have been well above average since spring. In fact, record warm SSTs have dominated the main tropical cyclone development region—from 10°N to 20°N between the coast of Africa and Central America (20°W – 80°W)—for five consecutive months (see the 2nd topic entry on this page). Combine that with lower-than-normal surface pressure basin wide and the fact that El Niño was not only ending but appeared poised to transition to La Niña conditions (which it did) in the tropical Pacific, both of which are factors that can lead to more than the usual number of storms, and forecasters had almost no choice but to set their sights rather high. Conditions appeared very favorable for a quick start to a long and busy season, not unlike 2005.

Problem is, that hasn’t happened. The tropical cyclones that have developed this year have struggled. Despite all the favorable features, it appears dry air and more importantly strong wind shear across the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico in June and July have kept storms in check. Typically, the atmosphere over the Atlantic Basin moistens significantly starting in August as the westward-moving Saharan dust outbreaks wane. And seasonal wind shear also becomes more conducive for storm development by August. Still, the next four months would need to see the pace of tropical storm and hurricane formation come fast and furious to realize the forecasts. It could happen: in 1995, 16 tropical storms and hurricanes, including five major hurricanes, formed one after another after another from the last days of July through the end of October, leaving just 10 days in the three-month period free of any storms. But that kind of hurricane history isn’t likely to repeat itself. Even 2005 had more storm-free days in the same portion of the season.

So what will forecasters do? Time will tell as two of the leading forecast teams—NOAA and the Colorado State University Tropical Meteorology Project, led by Phil Klotzbach and William Gray—update their forecasts this week. (Check these links for their updated forecasts: CSU (Aug. 4) and NOAA (Aug. 5).

Update …

Largely Unchanged Forecasts Point to Busy Months Ahead

With their August updates, hurricane season forecasters have left their predictions generally intact. The CSU forecast (pdf file) remains the same with 18 named storms total, 10 hurricanes, and 5 major hurricanes. After increasing its forecast in July by one named storm that was likely to be a hurricane, Tropical Storm Risk (TSR), a private British forecasting company, is back to its early June forecast numbers, with its August update (pdf file) again calling for about 18 named storms, 10 hurricanes, and 4-5 major hurricanes projected. NOAA shaved down the upper range of its seasonal forecast numbers while keeping the lower end of the range intact for named storms and hurricanes, and narrowing the range of major hurricane expected. Its updated forecast is for 14-20 named storms, 8-12 hurricanes, and 4-6 major hurricanes, versus its June forecast of 14-23 storms, 8-14 hurricanes and 3-7 major hurricanes. Florida State University lowered its prediction by 2, from 17 to 15 named storms and from 10 to 8 hurricanes.

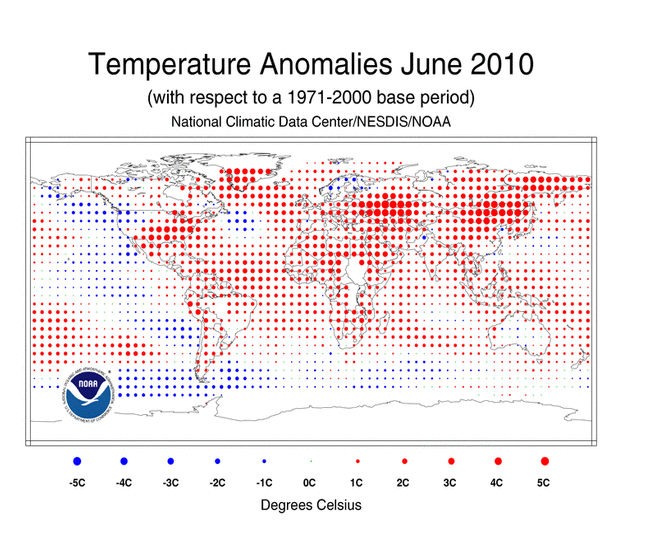

Mercury Rising, Snow Disappearing

This past June continued a recent spate of unprecedented heat around the world, as NOAA’s National Climatic Data Center (NCDC) announced it was the warmest June on record (the NCDC’s data extends back to 1880), making it the fourth consecutive month of record heat. The combined global land and ocean temperature for June was 16.2°C (61.1°F), placing it 0.68°C (1.22°F) higher than the twentieth-century average. Remarkably, it was the 304th consecutive month of global temperatures above the twentieth-century average. The last month that global temperatures were below that average was February of 1985.

March, April, and May of 2010 were also the warmest of their respective months on record, and the period of January-June is also the warmest ever recorded.

With the warmth came a striking decrease in snow, as NOAA announced that North American snow cover at the end of April was at its lowest point for that time of the year since satellite record keeping began in 1967, at 2.2 million square kilometers below average. This was just four months after the snowiest December on record, as well as significantly higher-than-n0rmal snow cover in January and February, demonstrating the profound ramifications of the warm temperatures that followed.

Oklahoma School of Meteorology Gets New Director

David Parsons started as the new director of the University of Oklahoma School of Meteorology this week. OU is the largest meteorology program in the nation, with nearly 400 undergraduate and graduate students. Parsons, who replaced Fred Carr, comes to the position from NCAR as a senior scientist and cochair of the THORPEX Project.

David Parsons started as the new director of the University of Oklahoma School of Meteorology this week. OU is the largest meteorology program in the nation, with nearly 400 undergraduate and graduate students. Parsons, who replaced Fred Carr, comes to the position from NCAR as a senior scientist and cochair of the THORPEX Project.

Parsons received his B.S. in meteorology from Rutgers University and his Ph.D. in atmospheric science from the University of Washington. His career has been multi-dimensional with major contributions to the field. He has written over 120 papers, book chapters, and reports, more than 40 of which appear in scholarly journals or refereed books. Parson’s research contributions span a wide range of subject matter, including advanced sounding and electromagnetic profiling technologies and techniques, mesoscale model parameterizations, extratroptical and tropical rainband physics and dynamics, and definitive dryline studies, to name just a few. Recent works include the role of transport and diffusion in the stable nocturnal boundary layer surrounding Salt Lake City, Utah. He has been nominated twice for the NCAR Publication Prize as well as the WMO Vaisala Award.

Named a Fellow of AMS in 2009. Parsons also served as panel chair on the Mesoscale Chapter for the AMS Monograph on Severe Local Storms, as editor of JAS, and was a member of the AMS Committee on Severe Local Storms.

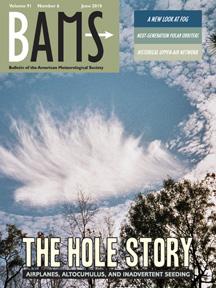

The Big Impact of BAMS

BAMS has done it again. After claiming the number one spot for Impact Factor on the Thompson Institute for Scientific Information (ISI) ranking in 2008, BAMS came in first in the Meteorology and Atmospheric Sciences category once again in 2009.

BAMS has done it again. After claiming the number one spot for Impact Factor on the Thompson Institute for Scientific Information (ISI) ranking in 2008, BAMS came in first in the Meteorology and Atmospheric Sciences category once again in 2009.

The impact factor, or IF, is a measure reflecting the average number of citations to articles published in science and social science journals. Devised by Eugene Garfield, the founder of the ISI (now part of Thomson Reuters), the IF is calculated yearly and journals are ranked taking into account two years of citations. The total number of citations for BAMS in 2009 was 9,074 with an IF of 6.123.

The IF is primarily used to compare different journals within a field, with larger impact factors suggesting greater influence, or impact, in the field. Four other AMS journals placed in the top twenty with Journal of Climate coming in at number five, Journal of Atmospheric Sciences at thirteen, Journal of Hydrometeorology at fifteen, and Monthly Weather Review at twenty. The newest AMS journal, Weather, Climate, and Society will appear in the IF rankings for the first time in 2011 when there is sufficient citation data to calculate a score.