A break from serious thinking for a moment….

They got too close. Way too close. But thanks to Mike Smith for pointing out this close encounter with a waterspout, which was fun until it was no longer so fun…Which led us to find this even more slick, calculated approach:

So is waterspout hunting the latest crazy extreme sport? Let’s hope not, though sometimes you’re in the right place at the right time:

That’s far cry from what this waterspout does to a ship off Singapore :

Camerman to child: “You want to go up in an airplane? I don’t think it’s a good idea!”

Hmmm, maybe airplanes are how all this got started in the first place:

Uncategorized

Stephen Schneider: Scientist, Communicator

by Peggy Lemone, AMS president (with thanks to Bob Chervin)

On 19 July, our community lost both a great scientist and a great communicator, Stephen H. Schneider. Dedicating his life to quantitative analysis of the physics of climate and climate change while still a graduate student, he soon became a leader in and major spokesman for the field. He spent most of his professional life at NCAR and then at Stanford.

My first real encounter with Steve Schneider was at an NCAR retreat in the 1970s. He was presenting a “back-of-the –envelope” calculation (on a hand-drawn envelope on the transparency) on climate change at a retreat in the Colorado mountains. He was energetic and enthusiastic, and able to distil his arguments into simple, easy-to-understand language. In the coming years, we all began to recognize that here was not only a gifted scientist, but a gifted communicator. It was not long before people in the media recognized that Steve had the ability to distil a complex problem into a short sound bite that was a lot more than “ear candy.”

Steve at the time was focusing on the cooling effects of aerosols, while his colleague Will Kellogg was investigating the warming effects of carbon dioxide. This inspired a display on our group bulletin board, with two newspaper articles, one about Steve and cooling, and one about Will and warming, beneath a copy of Robert Frost’s poem “Fire and Ice.” In his aerosol research, Steve rapidly moved on from “nuclear winter” to “nuclear autumn” and the impact of carbon dioxide. Like a good detective, he refined his opinions as the evidence came in, and he drew in colleagues from multiple disciplines to track the causes and impacts of climate change. He quickly became NCAR’s ambassador for climate change, writing several books, and continuing to explain the rapidly-evolving science to the public through the news media.

Sadly, he ended up having to do far more than simply explain the science to the public and policy-makers: increasing resistance to the findings of climate-change science put him and other climate scientists on the defensive – not so much against other atmospheric scientists as to private citizens. Indeed, in recent years, he, like other climate scientists, have received multiple threatening emails. As in the title of his last book, climate science has in some sense become a “contact sport,”with confrontation rather than reasoned discussion. In Steve’s words (from an interview in Stanford’s alumni magazine)

…in the old days when we had a Fourth Estate that did get the other side [of debates]—yes, they framed it in whether it was more or less likely to be true, the better ones did—at least everybody was hearing more than just their own opinion. What scares me about the blogosphere is if you only read your own folks, you have no way to understand where those bad guys are coming from. How are you going to negotiate with them when you’re in the same society? They’re not 100 percent wrong, you know? There’s something you have to learn from them and they have to learn from you. If you never read each other and you never have a civil discourse, then I get scared.

Only time will quiet the vigorous and sometimes unpleasant debate. But, in the meantime, I hope that we in the community can also find times and opportunities to share this important science with the public in non-confrontational and user-friendly ways. We owe that to Steve, the public, and ourselves.

For more details on Steve’s rich and productive life, see the Stanford University web site, and also the 13 August 2010 issue of Science, and the 19 August 2010 issue of Nature

The Road to Safer Driving Is Paved with Meteorology

Storm chasing is sometimes as much a gripping challenge of driving through nasty weather as it is a calculated pursuit of meteorological bounties.

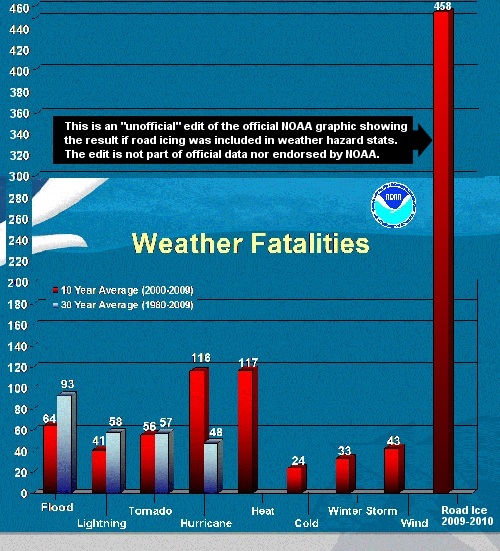

So perhaps it’s not so surprising that it took a storm chaser…Dan Robinson’s his name…to start a web site about the fatal hazard of ice and snow on our roads. Over half of the weather-related deaths on American roads each year are in wintry conditions.

Robinson took the liberty of tacking road statistics into the preliminary NOAA numbers for weather hazards (recently released for 2009 here).

The effect is striking, indeed, and a good lead in to Bill Hooke’s report from a Federal Highway Administration workshop today on road weather and the future of intelligent transportation systems.

Clearly we’ve got a lot of work to do and a lot of lives to save…Hooke, the AMS Policy Program Director, makes the case and points out some of the bumps in the road to better weather safety in your car.

The Aerographer's Advice

Ray Boylan, former chair of the AMS Broadcast Board, who died yesterday at age 76, was a Navy enlisted man who found his way into meteorology by a fluke. Maybe that’s why he never lost a homespun attitude toward celebrity and science that we ought to remember.

After training at airman’s prep in Norman, Oklahoma, in 1953, Boylan was casting about for the next assignment when he noticed that the Aerographer’s mate school was in Lakehurst, New Jersey—near home and best of all near his girlfriend.

So it was off to New Jersey for a career in meteorology. The Navy service was his only formal training in weather, and included some 2,000 hours as a hurricane hunter flight meteorologist. First assignment—flying straight into Camille in 1969:

Back in those days the Navy had the low level mission and the Air Force had the high level mission. Whatever the lowest cloud level was, we went in below those so that I could see the sea surface to keep the wind just forward of the left wing. That’s how we navigated in. I remember a fellow at a Rotary meeting who asked,

‘How many times do you hit downdrafts?’

‘Just once.’

Realizing that viewers had a realistic yes/no experience with rain, Boylan resisted using PoPs on the air, according to today’s Charlotte Observer obituary:

“I’d rather say, ‘It’s going to be scattered like fleas on a bulldog’s back – and if you’re close, you’ll get bitten.’ Or, ‘like freckles scattered across a pretty girl’s face.'”

Lamenting the hype of local TV news these days, Boylan told the WeatherBrains on their 19 February 2008 podcast,

One of the things I see now, is that every weather system that approaches a tv market is a storm system. Not every weather system is a storm system, but that vernacular is there.

Sometimes the medium gets in the glow of the medium’s eye. It’s kind of a narcissistic thing. The media looks at itself as absolutely invaluable. And it can be invaluable, but not if the media thinks so.

The work of the on air forecaster is not to impress, but in

Trying to get the forecast as right as you possibly can. Building the trust of the audience so that they’ll forgive even when you are wrong, And there’s no one out there in our business who hasn’t been wrong, and won’t be again, including myself. …If you can build that confidence and trust base, they’ll forgive you some of the small ones if you get the big one.

Speaking of building trust, Lakehurst turned out pretty well for Boylan. Fifty-five years later he would say, “The science and the girl are still with me.”

(Click here to download the audio of the full 20-minute WeatherBrains interview with Boylan.)

Climatology: Inverting the Infrastructure

Atmospheric science may not seem like a particularly subversive job, but from an information science perspective, it involves continually dismantling the infrastructure that it requires to survive. At least that’s the way Paul Edwards, Associate Professor of Information at the University of Michigan described climatology, and one other sister science, in an interesting hour-long interview on the radio show, “Against the Grain” last week. (Full audio is also available for download.)

In the interview Edwards describes how the weather observing and forecasting infrastructure works (skip to about the 29 minute mark if that’s familiar), then notes that climatology is the art of undoing all that:

To know anything about the climate of the world as a whole we have to look back at all those old [weather] records. …But then you need to know about how reliable those are. [Climate scientists] unpack all those old records and study them, scrutinize them and find out how they were made and what might be wrong with them–how they compare with each other, how they need to be adjusted, and all kinds of other things–in order to try to get a more precise and definitive record of the history of weather since records have been kept. That’s what I call infrastructural inversion. They take the weather infrastructure and they flip it on its head. They look at its guts.

In his book, The Vast Machine: Computer, Models, Climate Data, and the Politics of Global Warming, Edwards points out that people don’t realize how much of this unpacking—and with it multiple layers of numerical modeling–is necessary to turn observations into usable, consistent data for analysis and (ultimately) numerical weather and climate predictions. The relationship between data and models is complicated:

In all data there are modeled aspects, and in all models, there are lots of data. Now that sounds like it might be something specific to [climate] science, but …in any study of anything large in scope, you’ll find the same thing.

In part because of this “complicated relationship” between observations and models, there’s a lot of misunderstanding about what scientists mean when they talk about “uncertainty” in technical terms rather than in the colloquial sense of “not knowing”. Says Edwards,

We will always keep on finding out more about how people learned about the weather in the past and will always find ways to fix it a little bit. It doesn’t mean [the climate record] will change randomly or in some really unexpected way. That’s very unlikely at this point. It means that it will bounce around within a range…and that range gets narrower and narrower. Our knowledge is getting better. It’s just that we’ll never fix on a single exact set of numbers that describes the history of weather.

Climatology is not alone in this perpetual unpacking of infrastructure. Economists seem like they know all about what’s going on today with their indexes, Gross Domestic Products, inflation rates, and money supply numbers. That’s like meteorology. But to put together an accurate history of the economy, they have to do a huge amount of modeling and historical research to piece together incongruous sources from different countries.

There is a thing called national income accounting that has been standardized by the United Nations. It wasn’t really applied very universally until after the Cold War….Just to find out the GDP of nations you have to compare apples and oranges and find out what the differences are.

And to go back as recently as the 1930s?

You would have to do the same things the climate scientists have to do…invert the infrastructure.

They Still Make Them Like They Used To

This summer, the Catlin Arctic Survey team became the first explorers to ever take ocean water samples at the North Pole. The three-person team covered 500 miles over 2 1/2 months in their expedition across sea ice off the coast of Greenland. On the way they were met with numerous obstacles: a persistent southerly drift that regularly pushed them backward, strong headwinds, ice cracks opening under their tent, dangerously thin ice, and areas of open water they had to swim across.

They persisted through it all, measuring ice thickness, drilling ice cores, and collecting water samples (see the video below) and plankton data. They hope their research will provide insight into the effects of carbon dioxide on local marine life and Arctic Ocean acidification.

The heartiness of the Catlin team reminds us of the rich history of polar exploration in the name of meteorology. Historian Roger Turner of the University of Pennsylvania gave a fascinating presentation at the AMS Annual Meeting in Atlanta about the origins of the tradition, spotlighting the group of young Scandinavian meteorologists who studied under Vilhelm Bjerknes in Bergen, Norway. They were vital contributors to numerous Arctic expeditions in the 1920s.

This first wave of Bergen School meteorologists was well-suited to polar exploration, where they contributed their familiarity with the Far North conditions as well as their new understanding of upper-air dynamics. But Turner argues that their affinity for outdoors activities–particularly in the harsh conditions of the Arctic–also set them apart from others in their generation and, by implication, from the desk-bound meteorologists today.

We think those hardy meteorological pioneers of yesteryear would appreciate the intrepid scientific spirit of the Catlin team.

Shoes for Showers

Finally… incontrovertible proof that precip distribution is a step function.

Finally… incontrovertible proof that precip distribution is a step function.

From Regina Regis, in Italy. 69 Euros.

Putting Out Fires with Meteorology

San Diego Gas and Electric has embarked on an ambitious weather-monitoring effort that should warm the hearts of meteorologists–whose help the utility may still need to solve a larger wildfire safety controversy.

SDG&E recently installed 94 solar-powered weather monitoring systems on utility poles scattered in rugged rural San Diego County, where few weather observations are currently available. The purpose is to help prevent and control forest fires during Santa Ana winds. The plan has won plaudits from local fire chiefs and meteorologists alike, since the data will be available to National Weather Service forecasters and models as well as the utility’s own decision makers.

“That makes San Diego the most heavily weather instrumented place on Planet Earth,” says broadcast meteorologist John Coleman in his report on the story for KUSI News.

SDG&E’s intensified interest in meteorological monitoring is precipitated by the hot water the company got into due to its role in forest fires in 2007: Electricity arcing from power lines is blamed for three fires that year that killed two people and destroyed 1,300 homes in rural areas around San Diego. While not acknowledging fault, the company has compensated insurance companies to the tune of over $700 million.

To improve safety the company came up with plans last year to shut off the grid for up to 120,000 people in rural areas if dry weather turns windy–classic Santa Ana conditions. The shut off would initiate in 56 m.p.h. winds, the design standard for much of the power system, and then power would be restored when sustained winds remained below 40 m.p.h. assuming the lines prove reliable. Southern California Edison used a similar cut-off tactic in 2003 with relatively positive reaction from customers, but the company later aggressively cleared areas around power lines and has not utilized the plan since.

SDG&E, by contrast, had been in federal mediation for months with customers angry about the shut-off plan. One of the main gripes about the plan has been that the power company didn”t expect to warn customers about the outages. The company said it couldn’t predict the winds on a sufficiently localized basis.

Clearly the controversy could be alleviated by enhanced meteorology with the newly established weather stations. Brian D’Agostino, the local meteorologist who helped SDG&E design the weather monitoring strategy told KGTV Channel 10 News:

We’re taking a lot of areas where we always just figured the winds were at a certain speed and now we’re going to know for sure….Right now, the National Weather Service gets its information once every hour. Now, we’re able to provide it with data every 10 minutes.

Sit Tight: You Might Be (Over)-Warned

On his blog this week, Mike Smith, CCM (and an AMS Fellow) discusses the common air passenger’s frustration  with seat belt warning signs that stay on for hours even when the weather is clear and turbulence-free. But Smith’s post is interesting reading also because it is a uniquely meteorologist‘s frustration with this form of over-warning. He argues that we know enough about clear-air turbulence (and thunderstorm avoidance) that it makes little sense to tie people down to their seats for so long.

with seat belt warning signs that stay on for hours even when the weather is clear and turbulence-free. But Smith’s post is interesting reading also because it is a uniquely meteorologist‘s frustration with this form of over-warning. He argues that we know enough about clear-air turbulence (and thunderstorm avoidance) that it makes little sense to tie people down to their seats for so long.

As we know from experience, most recently the United Airlines flight on July 20th in which two dozen people were injured, the seat belt signs are indeed important. More than 90 percent of all injuries on turbulent flights happen when people don’t buckle up appropriately. But Smith observes,

I fear pilots are — too often — training their passengers not to observe the sign. Fly enough miles with the seat belt sign on but no turbulence and you’re tempted to get up, sign or no sign.

Overuse of the warning sign is well known in aviation circles. From the pilot’s point of view, there’s a lot more to this situation than just meteorology. Some pilots apparently forget the light is on (one critic here says, “I think pilots pay about as much attention to the seatbelt sign as the passengers do”) and in any case airline policies and pilot predilections vary. In the United States, in particular, airlines must deal with liability: passengers frequently sue them when injuries are caused by turbulence. (One wag dubs the seat-belt sign the “anti-litigation switch.”)

Can science overcome this situation? Clear air turbulence has been a topic of research since bomber pilots encountered the jet stream in World War II—the Navy Bureau of Aeronautics’ Project AROWA in the 1950s researched the problem of forecasting clear air turbulence (for example: this paper in the AMS archives). Research on radar techniques for detecting CAT started to take off in the 1970s, and much progress is being made even now (here’s a good example of recent developments in CAT forecasting); it remains an area of intense research and product development.

Ultimately, improved CAT warnings are at the mercy of the confidence that customers (in this case, the pilots) have. Even if pilots do know the latest science or know how to use the latest gadgets, low confidence in new tools can mean excessive warning, which means careless passengers, which in turn means frustrated meteorologists, and an ongoing challenge for the aviation weather community.

A Community Living Up to Its Name

by William Hooke, AMS Policy Program Director

Last-day thoughts from the AMS Summer Community Meeting this week. From a post in the AMS project, Living On the Real World

The term “community” shouldn’t be applied to any enterprise cheaply; there should be a high bar. Dictionary.com gives several definitions for “community.” The third of these is most pertinent here:

“a social, religious, occupational, or other group sharing common characteristics or interests and perceived or perceiving itself as distinct in some respect from the larger society within which it exists (usually prec. by the ): the business community; the community of scholars.” [italics in the original]

Coming across that last phrase was a pleasant surprise; it’s been with me since ninth grade. Then I was a student at Wilkins Township Junior High, just outside Pittsburgh. (The school was kind of tough and my ambition was to graduate with all my teeth, but that’s another story.) Our science course that year focused on the weather. The course made an impression on me that lasted over half a century. In part this was because the Earth sciences became my career, but in addition there were two other reasons. First, our teacher, though she was nominally the science teacher, was uncomfortable with science. (This was before the AMS started its Education Program; today’s science teachers have no excuse!). So, our textbook notwithstanding, we spent the entire semester (!!!) on weather superstitions/folklore…”mares’ tails make lofty ships carry low sails,” etc. The semester seemed to me to drag on forever; I’m sure she felt the same way. Second, the opening page of that textbook stated, and I quote, from memory, “Scientists are a community of scholars engaged in a common search for knowledge.” As the son of a scientist, even then the thought inspired me. I wanted to be part of such a community.

In college I majored in physics, and then entered graduate studies at the University of Chicago. I started out at the Institute for the Study of Metals. But there, and then, competition, not cooperation, was the word. It was dog eat dog. The field seemed over-populated. A lot of people were working on the same problem (the de Haas-van Alphen effect, which had been around about 35 years), not sharing progress but keeping results to themselves, etc. After one year, I transferred to the Department of Geophysical Sciences after a year. What a breath of fresh air! There were more than enough problems to go around. Nobody was going to win a Nobel Prize. Growing rich was not in prospect; the geophysical scientists had all taken vows of poverty. As a result, or maybe because the field attracted cooperative types, we all got along! The contrast with physics was palpable.

Today we can all feel more privileged than ever to be part of this community.