Off the coast of Antarctica, beyond the McMurdo Station research center at the southwestern tip of Ross Island, lies Hut Point, where in 1902 Robert Falcon Scott and his crew established a base camp for their Discovery Expedition. Scott’s ship, the Discovery, would soon thereafter become encased in ice at Hut Point, and would remain there until the ice broke up two years later.

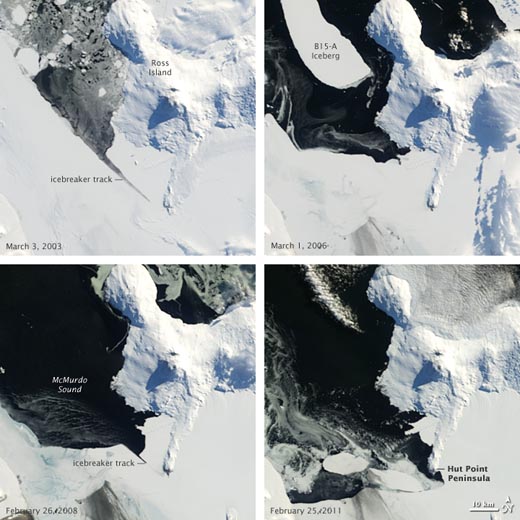

Given recent events, it appears that Scott (and his ship) could have had it much worse. Sea levels in McMurdo Sound off the southwestern coast of Ross Island have recently reached their lowest levels since 1998, and last month, the area around the tip of Hut Point became free of ice for the first time in more than 10 years. The pictures below, taken by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer on NASA’s Terra satellite and made public by NASA’s Earth Observatory, show the progression of the ice melt in the Sound dating back to 2003. The upper-right image shows a chunk of the B-15 iceberg, which when whole exerted a significant influence on local ocean and wind currents and on sea ice in the Sound. After the iceberg broke into pieces, warmer currents gradually dissipated the ice in the Sound; the image at the lower right, taken on February 25, shows open water around Hut Point.

Of course, icebreakers (their tracks are visible in both of the left-hand photos) can now prevent ships from being trapped and research parties from being stranded. Scott could have used that kind of help in 1902…

Uncategorized

Hot Off the Presses

Today marks the release of a new AMS publication, Economic and Societal Impacts of Tornadoes. The book examines data on tornadoes and tornado casualties through the eyes of a pair of economists, Kevin Simmons and Daniel Sutter, whose personal experiences in the May 3-4 1999 Oklahoma tornadoes led to a project that explored ways to minimize tornado casualties. The book culminates more than 10 years of research. (At the Annual Meeting in Seattle, the authors talked to The Front Page about their new book.)

Today marks the release of a new AMS publication, Economic and Societal Impacts of Tornadoes. The book examines data on tornadoes and tornado casualties through the eyes of a pair of economists, Kevin Simmons and Daniel Sutter, whose personal experiences in the May 3-4 1999 Oklahoma tornadoes led to a project that explored ways to minimize tornado casualties. The book culminates more than 10 years of research. (At the Annual Meeting in Seattle, the authors talked to The Front Page about their new book.)

Check out the online bookstore to purchase this and other AMS titles.

Here Comes the Sun–All 360 Degrees

The understanding and forecasting of space weather could take great steps forward with the help of NASA’s Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory (STEREO) mission, which recently captured the first-ever images taken simultaneously from opposite sides of the sun. NASA launched two STEREO probes in October of 2006, and on February 6 they finally reached their positions 180 degrees apart from each other, where they could each photograph half of the sun. The STEREO probes are tuned to wavelengths of extreme ultraviolet radiation that will allow them to monitor such solar activity as sunspots, flares, tsunamis, and magnetic filaments, and the probes’ positioning means that this activity will never be hidden, so storms originating from the far side of the sun will no longer be a surprise. The 360-degree views will also facilitate the study of other solar phenomenon, such as the possibility that solar eruptions on opposite sides of the sun can gain intensity by feeding off each other. The NASA clip below includes video of the historic 360-degree view.

The Weather Museum Names Its 2010 Heroes

The Weather Hero Award is given to individuals or groups who have demonstrated heroic qualities in science or math education, volunteer efforts in the meteorological community, or assistance to others during a weather crisis. The 2010 Weather Heroes honored were the American Meteorological Society, KHOU-TV in Houston, and Kenneth Graham, meteorologist-in-charge of the NWS New Orleans/Baton Rouge office.

The AMS was recognized for developing and hosting WeatherFest for the past ten years. WeatherFest is the interactive science and weather fair at the Annual Meeting each year. It is designed to instill a love of math and science in children of all ages, encouraging careers in these and other science and engineering fields. AMS Executive Director Keith Seitter accepted the award on behalf of the Society. “While we are thrilled to display this award at AMS Headquarters,” he comments, “the real recipients are the hundreds of volunteers who have given so generously of their time and have made WeatherFest such a success over the past decade.”

KHOU-TV was honored for hosting Weather Day at the Houston Astros baseball field in fall of 2010. Weather Day was a unique educational field trip and learning opportunity that featured an interactive program about severe weather specific to the region. Over the course of the day, participants learned about hurricanes, thunderstorms, flooding, and weather safety—highlighted by video, experiments, trivia, and more.

Graham received the award for his support of the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill cleanup. As meteorologist-in-charge of the New Orleans/Baton Rouge forecast office in Slidell, Louisiana, Graham started providing weather forecasts related to the disaster immediately following the nighttime explosion. NWS forecasters played a major role protecting the safety of everyone working to mitigate and clean up the oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico.

The awards were presented at the center’s third Annual Groundhog Day Gala and its fifth annual Weather Hero Awards on 2 February 2011.

The Weather Research Center opened The John C. Freeman Weather Museum in 2006. As well as housing nine permanent exhibits, the museum also offers many exciting programs including weather camps, boy/girl scout badge classes, teacher workshops, birthday parties and weather labs.

Commutageddon, Again and Again

Time and again this winter, blizzards and other snow and ice storms have trapped motorists on city streets and state highways, touching off firestorms of griping and finger pointing at local officials. Most recently, hundreds of motorists became stranded on Chicago’s Lake Shore Drive as 70 mph gusts buried vehicles during Monday’s mammoth Midwest snowstorm. Last week, commuters in the nation’s capital became victims of icy gridlock as an epic thump of snow landed on the Mid Atlantic states. And two weeks before, residents and travelers in northern Georgia abandoned their snowbound vehicles on the interstate loops around Atlanta, securing their shutdown for days until the snow and ice melted.

Before each of these crippling events, and historically many others, meteorologists, local and state law enforcement, the media, and city and state officials routinely cautioned and then warned drivers, even pleading with them, to avoid travel. Yet people continue to miss, misunderstand, or simply ignore the message for potentially dangerous winter storms to stay off the roads.

Obviously such messages can be more effective. While one might envision an intelligent transportation system warning drivers in real time when weather might create unbearable traffic conditions, such services are in their infancy, despite the proliferation of mobile GPS devices that include traffic updates. Not surprisingly, the 2011 AMS Annual Meeting in January on “Communicating Weather and Climate” offered a lot of findings about generating effective warnings. One presentation in particular—”The essentials of a weather warning message: what, where, when, and intensity”—focused directly on the issues raised by the recent snow snafu’s. In it, author Joel Curtis of the NWS in Juneau, Alaska, explains that in addition to the basic what, where, and when information, a warning must convey intensity to guide the level of response from the receiver.

Key to learning how to create and disseminate clear and concise warnings is understanding why useful information sometimes seems to fall on deaf ears. Studies such as the Hayden and Morss presentation “Storm surge and “certain death”: Interviews with Texas coastal residents following Hurricane Ike” and Renee Lertzman’s “Uncertain futures, anxious futures: psychological dimensions of how we talk about the weather” are moving the science of meteorological communication forward by figuring out how and why people are using the information they receive.

Post-event evaluation remains critical to improving not only dissemination but also the effectiveness of warnings and statements. In a blog post last week following D.C.’s drubbing of snow, Jason Samenow of the Washington Post’s Capital Weather Gang (CWG) wondered whether his team of forecasters, and its round-the-clock trumpeting of the epic event, along with the bevy of weather voices across the capital region could have done more to better warn people of the quick-hitting nightmare snowstorm now known as “Commutageddon.” He concluded that, other than smoothing over the sometimes uneven voice of local media even when there’s a clear signal for a disruptive storm, there needs to be a wider effort to get the word out about potential “weather emergencies, or emergencies of any type.” He sees technology advances that promote such social networking sites as Twitter and Facebook as new ways to “blast the message.”

Even with rapidly expanding technology, however, it’s important to recognize that simply offering information comes with the huge responsibility of making sure it’s available when the demand is greatest. As CWG reported recently in its blog post “Weather Service website falters at critical time,” the NWS learned the hard way this week the pitfalls of offering too much information. As the Midwest snowstorm was ramping up, the “unprecedented demand” of 15-20 million hits an hour on NWS websites led to pages loading sluggishly or not at all. According to NWS spokesman Curtis Carey: “The traffic was beyond the capacity we have in place. [It even] exceeded the week of Snowmageddon,” when there were two billion page views on a network that typically sees just 70 million page views a day.

So virtual gridlock now accompanies road gridlock? The communications challenges of a deep snow continue to accumulate…

2011 Meisinger Award Winner Working to Solve Hurricane Intensity Problem

NCAR researcher George Bryan received the 2011 Clarence Leroy Meisinger Award at the 91st AMS Annual Meeting in Seattle for innovative research into the explicit modeling, theory, and observations of convective-scale motions. With this award, the AMS honors promising young or early-career scientists who have demonstrated outstanding ability. “Early career” refers to scientists who are within 10 years of having earned their highest degree or are under 40 years of age when nominated.

The Front Page sought out Dr. Bryan to learn more about the specific problems he is working to solve with his colleagues at NCAR. “We’ve been doing numerical simulations of hurricanes in idealized environments trying to understand what regulates hurricane intensity,” he says. “One of the things we found was that small-scale turbulence is very important, small-scale being less than a kilometer scale—boundary layer eddies in the eyewall, and things like that. And so we’re hoping to take what we learned from that and apply it towards real-time forecasts and real-time numerical model simulations to better improve intensity.” In the interview, available below, Bryan says knowing this will give forecasters a better idea how strong a hurricane is likely to be when one does make landfall.

Making the Public Aware of the Science

by Skyler Goldman, Florida Institute of Technology, Student Contributor

I sometimes feel like the whole purpose—or at least the effective application—of meteorology depends on being able to communicate to people who are not as knowledgeable in our subject. And yet the difficulty of this task is overwhelming. This was acknowledged from the outset at the Presidential Forum on Monday.

“We don’t serve you, the scientists, very well, and I want to change that,” Claire Martin, the chief meteorologist of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation said of the communication between scientists and the public. It’s an important statement, and one that seemed to be agreed upon by the rest of the panel.

“Scientists live and die by how their work is represented,” Tom Skilling of WGN Chicago said, adding that if they are not represented well, then they have no interest in communicating with the broadcast meteorologists and other meteorologists who communicate with the general public. It’s an issue facing our entire field, especially with important climate change topics knocking on the door.

It’s a simple concept: if the scientists who are doing the work of studying our changing climate are not getting the credit they deserve nor getting their entire story out there accurately, then they could lose interest in dealing with those responsible for communicating the science. In a society of three-minute weather broadcasts and one-page weather reports, it’s a delicate balance between telling the whole story and leaving something out. Someone—either scientists or journalists—is not going to get their way. So how does our field get around it?

An audience member threw out an interesting point. If the public is paying for the research, then shouldn’t they be able to read the work in a language they understand? This scientist cited a paper he wrote in “regular” English as opposed to “scientific” English, and said that it was instantly rejected by the editor for sounding too “unintelligent.” This scientist suggested that journals publish two versions of every paper, one for the scientific community and one for the general public.

The idea is somewhat revolutionary, and it was denounced by another scientist who claimed that he wasn’t sure that the public would even “care about his work.” Why go through the trouble?

But shouldn’t the public get to decide what they care about? I think those of us in the sciences tend to overlook just how intelligent the public can be. Making more scientific work available to the public in plain language would increase awareness. Then, of course, the public would need to have access to such articles. Unless you’re in college or working in the field, you’re probably not even aware that these journal articles exist, let alone have a subscription. It’s not like you can browse meteorology journals at Barnes and Noble or Borders. Access to science should not be limited by a caste system based on wealth or education. It should be available to all so the public can make their own decisions. Perhaps the public would be better prepared for weather and climate if they could form their own opinions.

Tom Skilling said that we as meteorologists “haven’t done a good job of preparing the public [for climate change].” Martin Storksdieck added that we “have done a poor job of telling not only what we can do, but what we can’t.” Perhaps the scientists wouldn’t be misrepresented if the general public could read their work. Maybe we don’t have to re-write articles as the one scientist suggested, but it would be a start. Sure it requires more work, but whoever said communicating was easy?

Broadcast Meteorology Award Winner Conveys Serious Science, Serious Fun

Bryan Busby, chief meteorologist for KMBC-TV in Kansas City, is the 2011 recipient of The AMS Award for Broadcast Meteorology. Busby received his award Wednesday evening at the 91st AMS Awards Banquet, held at the Washington State Convention Center in Seattle.

Established in 1975, the AMS award for Broadcast Meteorology recognizes a broadcast meteorologist for sustained long-term contributions to the community through the broadcast media, or for outstanding work during a specific weather event. Busby , who is the number one-rated meteorologist in the Kansas City metro area, was selected as this year’s winner for outstanding weather communication, mentorship, and sustained dedication to the public, and for service to the AMS broadcast community.

Busby has been a fixture on TV in Kansas City for 26 years. The Front Page caught up with him to learn about how he connects to the community and delivers weather information and forecasts that viewers can easily understand and use. “Not everyone goes through dynamic meteorology, therefore the only way to relate to them is to give them an analogy or another term that they can relate to, and hopefully through that there’s some tacit education—they don’t know that they’re learning while just listening. That’s the key.”

During the interview, which you can view below, he relays tales of the fun the station has with him on-air each Ground Hog’s Day, as well as a touching moment where he tells about visiting a nursing home and talking with an elderly viewer who is a big fan: “I said, it must get lonely, since she outlived her husband, and all the grandkids moved away and all the kids moved away. And she said, ‘No, no. My friends visit me every day … you’re one of them.’ And it just hit me like a ton of bricks.” He says for someone to take away something meaningful from the very brief time he’s on and then feel comfortable enough to say something like that to him “still just blows me away.”

Remembering His Past, Diversity Award Winner Creates Opportunity for Others

J. Marshall Shepherd, professor of atmospheric sciences and geography at the University of Georgia, is the 2011 recipient of The Charles E. Anderson Award. The AMS is honoring Dr. Shepherd for his outstanding and sustained contributions in promoting diversity in the atmospheric sciences through educational and outreach activities for students and scientists in multiple institutions.

The Front Page caught up with Shepherd to learn about some of his accomplishments as well as the institutions he partners with in building diversity. In the interview, which you can watch below, Shepherd also reveals his philosophy for taking on this challenge. He says that although his parents were educators, he remembers how it was growing up in a single-parent home that was far from traditional. The experience helped him shape his beliefs: “I know that there are others out there with similar backgrounds and I think it’s important to kind of convey the philosophy that, regardless of what your background and your circumstances are, if you set goals, you work hard, and maintain a certain value, philosophy, and morals, then I think you can go as far as you want to go.”

Shepherd will receive The Charles E. Anderson Award, which is in the form of an inscribed wooden book, Wednesday evening at the the AMS Awards Banquet (Washington State Convention Center halls 6A-B-C-D).

Jule G. Charney Award Winner Honored for Advancing Frontier in Mountain Meteorology

Ronald B. Smith, Damon Wells Professor of Geology and Geophysics at Yale University, is the 2011 recipient of the Jule G. Charney Award. The award is in the form of a medallion. The Jule G. Charney Award is granted to individuals in recognition of highly significant research or development achievement in the atmospheric or hydrologic sciences. The AMS is honoring Dr. Smith for his fundamental contributions to our understanding of the influence of mountains on the atmosphere through both theoretical advances and insightful observations.

The Front Page spoke with Smith to learn more about him and his award-winning research. In the interview, which you can view below, he says that while he has been able to answer “maybe a third of the outstanding questions” about mountain meteorology in his career, recent graduates interested in this field of research will find many more that they can take on to advance the science.

Smith will receive The Jule G. Charney Award at Wednesday evening’s Awards Banquet (Washington State Convention Center halls 6A-B-C-D).