With the the NPOESS Preparatory Project (NPP) satellite launched successfully yesterday from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, satellite users will want to begin thinking about getting up to date on NPP at the AMS Annual Meeting. Here’s a quick link to the dozens of upcoming AMS Annual Meeting presentations related to the satellite and JPSS in general.

In particular consider attending the Tuesday (24 January,; 8:30 am) panel on “Expected Improvements from Satellite Technology on Operational Capabilities at the NWS, Navy, and Air Force.” The participants are the heads of those respective forecasting agencies–Jack Hayes, Fred Lewis, and James Pettigrew. AMS’s William Hooke moderates.

Also, on Monday (23 January at 11:45 am) Mitchell Goldberg et al. of the JPSS program will describe NPP and its place in the overall JPSS mission (the Joint Polar Orbiting Satellite System, is the civilian-side successor to NPOESS, which was the National Polar-Orbiting Environmental Satellite System). NPOESS was canceled in 2010.

Meanwhile, until we meet in New Orleans, here’s context about how the mission has evolved with the cancellation of the NPOESS. And here’s a NASA video describing NPP’s mission and capabilities:

Further, you’ll find a wealth of information about the NPP satellite and its genesis in the overall architecture of NPOESS, described in BAMS last year. The meeting program has more specifically about the five major instruments aboard, VIIRS (Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite; described here in BAMS), CriS (Cross-track infrared Sounder), ATMS (Advanced Technology Microwave Sounder), OMPS (Ozone Mapper Profiler Suite), and CERES (Clouds and the Earth’s Radiant Energy System; description in BAMS here).

We’ll undoubtedly post more about specific satellite-related sessions at the 2012 Annual Meeting in New Orleans as we approach January.

Uncategorized

Never Too Early To Complement Your Meteorology Skills

Dan Dowling, The Broadcast Meteorologist blogger, posted some useful advice yesterday for aspiring weathercasters about how to deal with inevitable on-camera jitters as they start their careers. The advice is worthwhile for all students or professional meteorologists looking to advance their careers–not just those who want to be on television.

Dowling points out that a lot weathercasters knew from an early age that they wanted to be meteorologists, but not many of them knew until much later that they were going into broadcasting. As a result, they developed their scientific skills from the start but not the confidence and polish that they’ll needed to communicate to an audience.

It takes time to develop effective on-camera manner, Dowling says, just like it takes time to learn how to write reports or to analyze weather observations properly, because all of these skills stem from maturation of deeper qualities, whether an ear for language and logic to write well, or mathematical understanding to use models and observations, or, in the case of presentation, solid belief in your own abilities:

You can work on talking slower, or stop fidgeting with your hands, or trying to smile more, but it likely all stems from a lack of being comfortable and confident. It’s also a challenge to teach out of a student because it’s usually something that just takes time. Just like jumping in a pool of cold water, it just takes time to get used to, and there is not a lot else you can do to speed up the process. If you are in high school, now is the time to start building your confidence. The students who get started sooner end up coming to college better equipped for the opportunities they will find there.

The blog relates a couple examples of successful Lyndon State College meteorology grads who got involved in broadcasting in high school, but specific experience of this kind not the only way to work on communication and confidence:

It all starts by pushing yourself outside of your comfort zone. If it’s a little scary, you are probably headed in the right direction. Try acting or singing in a play, or being in a band or chorus. Get out in front of people. Play a sport. Get involved with a speaking or debate club. Whatever you do, make it fun.

The interesting thing about this advice is that it applies in many meteorological jobs, not just broadcasting. Dowling’s points echo what experienced meteorologists have been telling attendees year after year at the AMS Student Conference: don’t neglect your communications skills. Employers are looking for the ability to write and speak well if you’re going into business or consulting, not to mention any sort of job interacting with the public.

It’s difficult to develop such versatility during student years, when you’re packing in the math and science (here’s an example of a teacher who tries to make it possible by integrating communication practice into the science curriculum). But it’s a lot harder to catch up quickly on fundamental skills like writing and public speaking later in life.

Latest Readings

The Front Page keeps an eye on the web for you, bookmarking interesting ideas, profiles, developments, and media related to the atmospheric sciences community that you might have missed in the daily flood of urgent news. Recent links from our Delicious bookmarks page:

Unusual Road to Atmospheric Science: A profile of Richard Anyah, UConn assistant professor who started out teaching high school math in his native Kenya.

Videos from 2011 Stephen H. Schneider Symposium are now online: talks and follow-up discussion in which the climate science community reflects on scientific progress and the challenges of communicating with policymakers and the public.

John Tyndall, Discoverer of the Greenhouse Effect: Podcast of Irish radio interview with Richard Somerville, author of “The Forgiving Air,” about the history of “greenhouse effect” science, IPCC, and climate change topics.

WeatherBill morphs into The Climate Corporation. With funding from tech industry giants, the company has rebranded itself to tailor information to agribusiness and others looking to adapt to climate variability and change.

Moon’s shadow creates a atmospheric wake. Researchers use GPS signals to detect high-altitude gravity waves moving through the atmosphere during the total solar eclipse of 2009.

Forecast Bright for Student Meteorologists. Profile of Howard University’s graduate student association for atmospheric science.

You can get these links automatically updated in your favorite reader via an RSS feed by visiting our links archive page on Delicious. Or keep watching the “Latest Readings” sidebar on The Front Page.

Python in New Orleans: Once Bitten, Quickly Smitten

The upcoming 2012 AMS Annual Meeting in New Orleans is only the second with a whole symposium devoted to the use of Python programming language in the atmospheric sciences. The first was last year’s meeting in Seattle.

The quick return of Python to the conference program–including beginning and advanced short courses over the weekend (21-22 January)–suggests what a growing community of modelers and programmers already knows. Once they’ve encountered the Python language, people tend to become devotees.

“Python is an elegant and robust programming language that combines the power and flexibility of traditional compiled languages with the ease-of-use of simpler scripting and interpreted languages,” according to Filipe Pires Fernandes of the School of Marine Science and Technology in New Bedford, Massachusetts, who presents Monday (23 January, 2 p.m.).

Python, for example, is at the heart of the National Weather Service’s graphical forecast editor (GFE) tool and thus at the basis of the usage of the whole gridded forecast product suite in effect over the last decade. “Python’s introspective capabilities permitted developers to build a tool framework in which forecasters could write simple expressions and apply them directly to the forecast process without the burden of needing to know details about data structures or user interfaces,” writes Thomas LeFebvre of NOAA, who will discuss (Tuesday, 24 January, 8:30 am) how “a large part of GFE’s success is the result of the rich set of features that Python offers.”

Symposium Chair Johnny Lin of North Park University produced a short video to explain the attraction of Python, now the “eighth most popular programming language in the world” and preview the upcoming symposium:

The symposium program features numerous new software packages, with many of the presentations demonstrating how Python is a solution to software quirks and limitations that have become more bothersome as technology advances. One presenter is using Python to display data and model output on Google Earth. Another developed a new Skew-T diagram and Hodograph visualization and research tool (SHARPY), recasting a standard program, SHARP, in Python. Explains Patrick Marsh of NOAA’s National Severe Storms Laboratory: “Unfortunately, SHARP utilizes several GEMPAK routines which makes compiling, let alone installing and using, a non-trivial task.”

Andrew Charles of the Bureau of Meteorology in Australia used Python to create a web-based tool to integrate contour plotting with GIS applications. “With ever increasing amounts of data being made available, the related increase in required storage means static plots are not a viable solution for the delivery of all maps to end users,” writes Charles about his (11:30 a.m. Tuesday) presentation. “Contour plots are one of the most used data visualisation techniques in meteorology and oceanography and yet, surprisingly, there are few available solutions for the generation of contour plots to be used as map overlays from live data sources.”

UCAR's Next President, Thomas Bogdan

The University Corporation for Atmospheric Research (UCAR) announced today that Thomas Bogdan will succeed Richard Anthes as its next president, beginning in January 2012.

Bogdan has been director of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Space Environment Center in Boulder, Colorado, since 2006. A Fellow of the AMS and current member of our Council, Bogdan moved to NOAA after a long stint at UCAR’s National Center for Atmospheric Research, beginning as a post-doc, moving up through the Scientist and administrative ranks, and eventually serving as Acting Director of NCAR’s Advanced Studies Program. From 2001-2003 Bogdan was Program Director for the National Science Foundation’s Solar-Terrestrial Research Section. He received his Ph.D. in physics at the University of Chicago in 1984.

You can hear a recent interview with Bogdan about space weather on Colorado Public Radio.

Or watch his presentation about space weather from 2007 at the Commercial Space Transportation Conference:

AMS Climate Course To Reach 100 More Minority-Serving Institutions

The AMS Education Program has been awarded a grant by the National Science Foundation (NSF) to implement the AMS Climate Studies course at 100 minority-serving institutions (MSIs) over a five-year period. The project will focus on introducing and enhancing geoscience coursework at MSIs nationwide, especially those that are signatories to the American College & University Presidents’ Climate Commitment (ACUPCC) and/or members of the Louis Stokes Alliances for Minority Participation. AMS is partnering with Second Nature, the non-profit organization administering the ACUPCC.

“This national network involves more than 670 colleges and universities who are committed to eliminating net greenhouse gas emissions from campus operations by promoting the education and research needed for the rest of society to do the same,” explains Jim Brey, director of the AMS Education Program. “AMS and Second Nature will work together to demonstrate to current and potential MSI signatories how AMS Climate Studies introduces or enhances sustainability-focused curricula.”

In the first four years of the project, AMS will hold a weeklong AMS Climate Studies course implementation workshops for about 25 MSI faculty members. The annual workshops will feature scientists from NOAA, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, University of Maryland, Howard University, George Mason University, and other Washington, DC area institutions. Faculty will initially offer AMS Climate Studies in the year following workshop attendance and colleges that successfully implement AMS Climate Studies will be encouraged to build a focused geoscience curricula area by also offering AMS Weather Studies and AMS Ocean Studies.

“The major outcomes of this project will be a large network of faculty trained as change agents in their institutions, sustained offering of AMS undergraduate courses within MSIs, and the introduction of thousands of MSI students to the geosciences,” comments Brey. He notes that this project builds on the success of similar NSF-supported programs for MSI faculty implementing the AMS Weather Studies and AMS Ocean Studies courses, which together have reached 200 MSIs and over 18,000 MSI students. “We’re looking forward to working with Second Nature to continue to expand the climate course and the education that it represents.”

A Breakthrough for Antarctic Research

“It’s a big relief.”

That’s how Karl Erb, head of National Science Foundation’s Office of Polar Programs, sums up the feelings of most researchers at McMurdo Station, the headquarters of U.S. scientific research in Antarctica. The station was in danger of having its operations limited–or even of being shuttered–for at least this austral summer after the Swedish government recently announced that they would not be able to provide the Oden, the icebreaker/research vessel that the NSF has been leasing and which has been carving a path to McMurdo since 2006. Sweden claimed it needed to keep the vessel close to home after two consecutive severe winters bottled up shipping lanes in the Baltic Sea. (More recently, the Swedish government announced a five-year agreement to lease the ship to Finland for use in the Baltic’s Gulf of Bothnia.)

So the NSF, which oversees the U.S. Antarctic Program, looked elsewhere. Unfortunately, the three U.S. Coast Guard icebreakers are unable to handle the task: one is scheduled for decommission this month, one is being renovated and won’t be ready for at least two years, and the third is simply not designed for such a strenuous task as breaking through to McMurdo. With time running out to guarantee shipment of fuel and other supplies necessary to keep McMurdo operating through this austral summer, the NSF secured an agreement with a Russian vessel, the Vladimir Ignatyuk, to cut through the ice this year, and perhaps for the following two years if it’s needed. The Ignatyuk has carried out similar duties for other nations in the past, but unlike the Oden, it is not a research vessel. Scientists hoping to conduct ship-based research will have to scramble to hitch a ride on other vessels headed for the Antarctic region.

It's Not the Heat, It's the Aridity

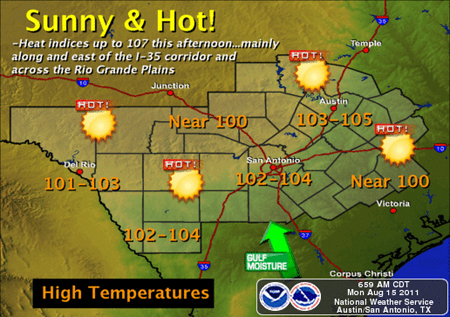

Monday’s NWS weather map looked all too familiar to most Texans. It’s been a summer of blazing sunshine and record-setting heat throughout most of the state, with so many new milestones being reached that it’s been hard to keep up.

According to the National Climatic Data Center’s national overview, July was the warmest month in state history (87.1°F; the previous average high was 86.5°F in July of 1998). Additionally, state climatologist John Nielsen-Gammon recently announced that Texas just went through its worst one-year drought on record (rainfall data goes back to 1895). At the end of July, the state had received only 15.16 inches of rain over the previous 12 months, breaking an 86-year-old record. And the year-to-date precipitation total of 6.53 inches was also a record low through the end of July, and 9.5 inches less than the historical average. According to the U.S. Drought Monitor, more than 75% of Texas is now in “exceptional” drought conditions, and last month’s rainfall total of 0.72 inches was the 3rd-driest July in state history.

“Never before has so little rain been recorded prior to and during the primary growing season for crops, plants, and warm-season grasses,” said Nielsen-Gammon.

And there appears to be no immediate end to the oppressive heat: recent forecasts predict at least another week of 100-degree temperatures in most of the state.

The conditions in Texas are typical of what much of the South has been experiencing this summer. Here are a few other numbers to chew on (preferably while you’re sitting in the shade with a tall glass of lemonade):

- According to NCDC, Oklahoma’s average temperature in July was 88.9°F, which is not only the warmest month in the state’s history, but the warmest month in any state, ever! (Oklahoma also held the previous record, which was 88.1°F in July of 1954.)

- The South climate region–which comprises Arkansas, Kansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma, and Texas–had an average July temperature of 86.1°F, making it the hottest month of any climate region on record. The previous record, also set in the South region, was 85.9°F in July of 1980.

- The average July temperature for the nation was 76.96°F, the 4th-warmest July–as well as the 4th-warmest month–on record, after Julys in 1936 (77.43°F), 2006 (77.26°F), and 1934 (77.00°F).

Every state in the country had at least one day of record-high temperatures in July. More U. S. climate records set during the month can be found here.

Industrial Air Pollution State by State

According to a study conducted by the Natural Resources Defense Council, an environmental advocacy organization, Ohio emits more toxic air pollution emitted from electricity-producing coal- and oil-fired power plants than any state in the country. The study utilized 2009 data taken from the Environmental Protection Agency’s Toxics Release Inventory, a database of emissions self-reported by industrial and other facilities across the United States. The report notes that 771 million pounds of toxic chemicals were released into the air in 2009 by U.S. industries, including metal, paper, food and beverage, and chemical companies. Of all the sectors mentioned in the study, power plants emitted by far the most air pollution (almost 382 million pounds), with Ohio contributing more than 44 million pounds to that figure, or about 12%. The full report can be viewed here.

The 20 states with the most toxic air pollution from power plants are:

- Ohio

- Pennsylvania

- Florida

- Kentucky

- Maryland

- Indiana

- Michigan

- West Virginia

- Georgia

- North Carolina

- South Carolina

- Alabama

- Texas

- Virginia

- Tennessee

- Missouri

- Illinois

- Wisconsin

- New Hampshire

- Iowa

Bridging Disciplines: Joint Sessions at the 2012 Annual

by Ward Seguin, 2012 AMS Annual Meeting Chair

For many years, organizers of the Annual Meeting have encouraged conferences to join forces to host joint sessions for the purpose of sharing presentations of mutual interest. A few years ago, organizers of the Annual Meeting proposed themed joint sessions that focused on the theme of the Annual Meeting.

Concerned that conferences participating in the Annual Meeting might not understand the purpose of joint sessions and, in particular, themed joint sessions, this year’s organizers decided to start the planning process early. At the 2011 Annual Meeting in Seattle, organizers for the 2012 meeting met with all of the conference committees holding meetings in Seattle to encourage future participation in the themed joint sessions. This was followed by e-mail contacts in February designed to reach those conference committees not present at the Seattle meeting.

In April, the conferences were asked to propose themed joint sessions focusing on AMS President Jon Malay’s 2012 theme of “Technology in Research and Operations–How We Got Here and Where We’re Going.“ The response from the conferences was outstanding, as 20 themed joint sessions are currently being organized. With so many conferences holding meetings in January, themed joint sessions encourage sharing of information among the government, academia, and the private sector in diverse subdisciplines. Participants are able to share their experiences of common problems and solutions, and attendees are able to take in papers related to the theme without having to move from one session to another.

Because the 2012 Annual Meeting theme is so broad, the range of topics being covered by the joint sessions provides an excellent opportunity for diverse conferences to come together. For example, one session–jointly hosted by the 10th Conference on Artificial Intelligence Applications to Environmental Science and the 18th Conference on Satellite Meteorology, Oceanography, and Climatology–is titled “Artificial Intelligence Methods Applied to Satellite Remote Sensing.” Another themed joint session, “Recent Advances in Data Management Technologies and Data Services,” will be hosted by the 28th Conference on Interactive Information Processing Systems (IIPS) and the Second Conference on Transition of Research to Operations: Successes, Plans, and Challenges. Still another session will focus on “Extreme Weather and Climate Change” and will be hosted by the Seventh Symposium on Policy and Socio-Economic Research, the 24th Conference on Climate Variability and Change, and the 21st Symposium on Education.

The format of themed joint session will include distinguished invited speakers, panel discussions, and submitted papers. Jon Malay’s chosen theme is allowing some very diverse conferences to focus together on some of today’s research and operations challenges through technology.

The deadline for abstract submissions for these sessions is August 1, and abstracts can be submitted on the AMS website at the abstracts submissions page.