As Typhoon Hagupit (Ruby) headed their way this weekend, Filipinos began to show they were a people far too experienced in the ways of typhoons.

Anxiety mixed with prudence. 500,000 people evacuated to safer quarters. Many residents of Tacloban–the city hardest hit by last year’s disastrous Typhoon Haiyan—took shelter in the local stadium. Others stocked up with food and other supplies. The city’s deputy mayor told the BBC, “It’s stirring up a lot of emotions in our hearts and bringing back so many painful memories.”

Those who study severe weather warnings are increasingly noticing this phenomenon: whether by fear or familiarity, people with prior experience have a peculiarly complex reaction to impending severe weather.

For example, a succession of well predicted tornadoes hit central Oklahoma within a short span in May 2013. During the third outbreak of that period, public reaction went awry. Before meteorologists could warn of the dangers of fleeing by car, residents hit the roads and caused potentially catastrophic traffic jams. The spontaneous evacuation, unlike any seen previously for a tornado, exposed the public to great risks.

In a paper to be presented at the AMS Annual Meeting next month at the Phoenix Convention Center (Wednesday, 7 January, 11:15 a.m., Room 226AB), Julia Ross and colleagues will analyze the effects of experience on the public’s “freak out” response to these tornadoes.

Quoting a recent paper by Silver and Andrey in the AMS journal, Weather, Climate, and Society, Ross et al. note that direct experience with hazards amplifies risk perception. But their survey results show both reasoned and fear-driven reactions to the warnings—and possibly some regionally specific preferences as well.

(In the presentation to follow Ross et al. at the Annual Meeting, Lisa Dilling and colleagues analyze the opposite of a wary, seasoned public. They report on the effect of surprise in the Boulder, Colorado, floods last year.)

If anyone knows typhoons, it’s the people of the Philippines. Supertyphoon Haiyan, which killed 7,000 a year ago, was but one of six different tropical cyclones that have killed more than 1,000 Filipinos in the past decade.

This time around authorities say they’re aiming for zero casualties. But there’s more than just anxiety to deal with. It takes time to rebuild from a blow like Haiyan. A Haiyan survivor in Tacloban told the Associated Press, “I’m scared. “I’m praying to God not to let another disaster strike us again. We haven’t recovered from the first.”

News

Hangout with the Experts This Thursday

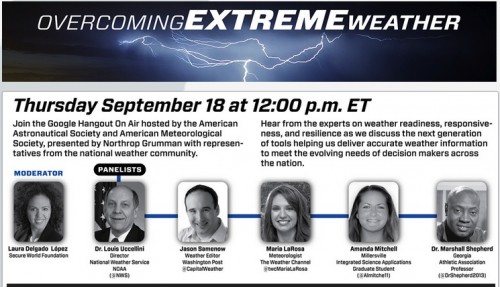

Where can you hang out with two former AMS presidents, the Washington Post weather editor, a Weather Channel meteorologist, and a grad student specializing in the latest geoinformatics technology and converse about extreme weather and the technology taking forecasting into the future?

Surely one answer is the next AMS Annual Meeting, in Phoenix, where the buzz is going to center on “fulfilling the vision of weather, water, and climate information for every need, time, and place.” Extreme weather will feature early and often in that week-long marathon of conversation.

That’s not coming up until January, however. If you’re looking for a singular opportunity to rub shoulders with the experts now, this Thursday brings a great opportunity.

Northrup Grumman, along with co-hosts the AMS and the American Astronautical Society, is presenting a Google Hangout on Air Thursday September 18th at Noon Eastern Time that might be just the conversation to you started thinking about the meteorological future. The Hangout will bring together leaders in the AMS community discussing challenges in forecasting and preparing for extreme weather. Like the Annual Meeting in Phoenix, the conversation will revolve around advances in science and technology that allow delivery of better information to protect life and property.

The participants bring a potent mix of perspectives and expertise: National Weather Service Director Louis Uccellini, Univ. of Georgia professor Marshall Shepherd, Weather Channel meteorologist Maria LaRosa, geoinformatics specialist Amanda Mitchell, and Washington Post weather editor Jason Samenow. Both Shepherd and Uccellini are AMS past presidents. The moderator is Laura Delgado Lopez of the Secure World Foundation, whose expertise is space policy and Earth observing systems.

You can tune in to this one hour live streaming digital event at www.northropgrumman.com/extremeweather. Join the conversation on Twitter and send weather questions ahead of time to be answered during the Hangout using #ExtremeWx.

New Standard Aims to Improve Tornado, Severe Wind Estimates

By Jim LaDue, NWS Warning Decision Training Branch

For more than four decades, the go-to for rating tornadoes has been the Fujita Scale, and in the last eight years, the Enhanced Fujita Scale, or EF Scale. Soon, scientists and NWS field teams will have a new and powerful benchmark by which to gauge the extreme winds in tornadoes and other severe wind events.

The American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) has approved the EF Scale Stakeholder Group’s proposal to develop a new standard for estimating wind speeds in tornadoes. This standard will allow, for the first time, a rigorous process to improve not only the EF-scale but to adopt new methods to assign wind speed ratings to tornadic and other wind events.

The intent is to standardize methods. According to the ASCE blog, “The content of the standard would include improvements to the existing damage-based EF scale to address known problems and limitations.” ASCE went on to state that the data used for estimating wind speeds would be archived.

The EF Scale Stakeholders Group, composed of meteorologists, wind and structural engineers, a plant biologist, and a hydrologist, held a series of meetings over the past year to discuss methods available to provide wind speed estimations. The consensus among the group is that many methods exist in addition to that used in the EF Scale today. These include mobile Doppler radar, tree-fall pattern analysis, structural forensics, and in situ measurements. The group also discussed ways that the EF Scale could be improved through the correction of current damage indicators and by adding new ones. The outcome of these discussions is available online.

The new standard will be housed under the Structural Engineering Institute (SEI) of the ASCE. Users of the standard include but are not limited to wind, structural, and forensic engineers, meteorologists, climatologists, forest biologists, risk analysts, emergency managers, building and infrastructure designers, and the media.

Interested parties are encouraged to apply to the committee, selecting Membership Category as either a General member with full voting privileges or as an Associate member with optional voting capabilities. Membership in ASCE is not required to serve on an ASCE Standards Committee.

The online application form to join the committee is available at http://www.asce.org/codes-standards/applicationform/.

The new committee will be chaired by Jim LaDue and cochaired by Marc Levitan of the National Institute of Standards and Technology. For more information or questions about joining the committee, please contact us at james . g . ladue @ noaa . gov and marc . levitan @ nist . gov.

Moving Mountains, Not Meteorology

If you attended the joint AMS conferences—on Applied Climatology and on Meteorological Observation and Instrumentation—held in the shadow of Colorado’s Rocky Mountains last week, you encountered the rich diversity of presentations encapsulating the topics that preoccupy specialists these days.

You heard lessons learned from using familiar tools of the trade, the latest news about new technology, ways of observing drought, impacts of El Niño, and principles of wildfire management.

There was much advice about communicating to the public about climate change, and about the scientific basis presented by the National Climate Assessment. You heard advice from the folks at Climate Central. You delved into how to handle information delivery in the duress of extreme events.

If you’ve moved on to California this week for the AMS Conference on Broadcast Meteorology at Squaw Valley, you enter a different world, right? From the dark, craggy jumble of Precambrian sediments, granite, and gneiss, you’re now surrounded by the pale glow of Sierra Nevada granite. And from scientists focused on research, now you’re in the realm of communicators bringing science to mass media.

So, you’ll hear lessons learned from using familiar tools of the trade, the latest news about new technology, ways of observing drought, impacts of El Niño, and principles of wildfire management.

There will be much advice about communicating to the public about climate change, and about the scientific basis presented by the National Climate Assessment. You’ll get some advice from the folks at Climate Central. You’ll also delve into how to handle information delivery in the duress of extreme events.

Déjà vu? Copy-and-paste error?

No. For all the specializations and variations in interests that collectively constitute the American Meteorological Society, there’s a lot in common between even the seemingly disparate branches. The roots in science grow into all sorts of permutations. The mountains may shift, but that’s a mere backdrop for the constancy of meteorology and related sciences flourishing across the land.

Enjoy your meetings.

Time to Heed the Hurricane Season Forecast?

With this year’s Atlantic hurricane season getting underway, seasonal forecasts are collectively calling for a quieter-than-usual year in the Atlantic basin, which includes the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico. With busts in these forecasts as recent as last year, however, is this actually reassuring news?

Mark Powell, a NOAA hurricane researcher who is now working with Florida State University’s Center for Ocean-Atmospheric Prediction Studies, was quoted in a recent Palm Beach Daily News article saying such forecasts, which typically are made before the start of the six-month season, “just don’t have any skill this early.”

They practically don’t. The major players of Atlantic hurricane season forecasts—NOAA, Colorado State University (CSU), and the private British forecasting firm Tropical Storm Risk (TSR)—stipulate that there is only a small increase in skill with pre-season forecasts (i.e., how much better such forecasts are) compared to climatology in foretelling the number of named storms that will form in the Atlantic basin from June 1 to November 30. Supporting this, a talk by Eric Blake of the National Hurricane Center presented at the 29th AMS Conference on Hurricanes and Tropical Meteorology stated that NOAA’s May forecasts for anticipated numbers of storms and hurricanes are only slightly better than what climatology showed had occurred in the previous five seasons. Forecast skill does increase as the season nears its peak months: August, September, and October, which is when 70 percent of tropical storms and hurricanes form.

But even these “better” mid-season forecasts can be wrong. In 2013, early predictions for an active season remained high as September neared, yet the actual number of named storms (13) and especially hurricanes (just 2) fell short of most forecasts, which had been collectively predicting a blockbuster season with at least seven hurricanes and three major hurricanes. The long-term average number of named storms and hurricanes is 12 and 6, respectively. There wasn’t a single major hurricane sporting winds greater than 110 mph last year, when climatology said there should have been at least three. In a blog post at the end of last year’s season, Jeff Masters of WeatherUnderground.com detailed the reason the forecasts failed: the large-scale atmospheric circulation, which can’t be predicted more than a week or two out and isn’t part of seasonal forecasts, was not conducive to tropical cyclone formation.

In 2012, however, it was, and the opposite occurred. The number of named storms peaked at 19—not only well above average but also the third highest number of storms on record in a single season. Ten of these went on to become hurricanes, exceeding most seasonal forecasts including NOAA’s, which had called for an average Atlantic hurricane season prior to its start. CSU had projected in June of that year a relatively quiet hurricane season with 13 named storms and only 5 hurricanes. With twice that many hurricanes forming, the season blew the forecast out of the water, making it CSU’s worst bust in decades of predictions. Until 2013.

This year, however, hurricane season forecasters feel the chance of the development of El Niño by the fall is much higher than it was in 2012—70 percent this summer increasing to 80 percent by fall, according to NOAA’s 9 June El Niño status statement—which lends significant weight to the lower hurricane predictions.

Historically, El Niño stifles Atlantic hurricanes. The enormous slug of warmer-than-normal sea surface temperatures along the Eastern Pacific equator, which defines El Niño, imparts a shift in the atmosphere’s circulation that drives unusually strong winds at high altitudes across the tropical Atlantic Ocean during the season. The induced wind shear—a difference in both speed and direction between the surface and aloft—suppresses not only tropical cyclone development but also formation, tearing apart hurricane seedlings before they can organize.

Research in recent years (Journal of Climate: 2009, 2013), however, has shown that a very different effect can result from El Niño’s half-brother – an anomalous warming in the tropical Pacific that pools in the central rather than the eastern part of the ocean basin. When this occurs, as it did in 2004, it can actually amplify the Atlantic hurricane season. That year, four hurricanes—three of them major, including Charley with 150 mph winds—slammed Florida. There were 15 named storms that year.

No forecasters expect a repeat of the devastating 2004 hurricane season. But, already we’ve had a record eight hurricane seasons without landfall of a major hurricane in the United States nor any category hurricane striking Florida. The last one was Wilma in 2005, which hit as a major hurricane.

Whether or not forecasts are accurate this early in the season, the old adage still applies: it only takes one hurricane in your area to create disaster. So be prepared.

Calling All Weather Campers

Are you a student looking for a camp that provides more than the typical summertime experience? Something that will excite you about meteorology and STEM careers? Then weather camp might be the perfect place for you.

There are now more than a dozen summer weather camps for middle or high school students across the country (some are for commuters; others are residential). Along with hands-on experiences, campers can get a glimpse of the various careers associated with meteorology.

“These camps provide an amazing opportunity for students,” says Mike Mogil of How the Weatherworks, an organization that spearheads the camps. “The program works to broaden exposure to meteorology, the physics behind it, and more. Observation skill building is a key component of many of the camps.Campers are engaged in hands-on activities, field experiments, seminars, tours of research facilities, and other opportunities that expand their knowledge in these areas.”

Programs are run by various groups, including local museums, colleges and universities, and even some student AMS chapters. The camps are designed to encourage all students (with an emphasis on reaching bright, underrepresented populations) to consider science and engineering education in college and to increase the pipeline of talented and focused students pursuing careers in these areas. Partial funding for camps is provided by NOAA and many local businesses.

“The camps are an incredible way to help kids enjoy learning,” comments Mogil, an AMS CCM and CBM who often presents at the AMS Annual Student Conference.. “In the atmosphere of the camps, even the teachers become kids.”

Deadlines for camp registration are quickly approaching. If you are aware of other weather camps not listed here, please share them in the comments section of The Front Page.

If you have any questions about the overall camp program, please contact Mike directly.

National camp page

Lyndon State College – Lyndonville, VT

Blue Hill Observatory – Milton, MA (Weather Programs)

City University of New York – New York, NY

2014 National High School Weather Camps

– Jackson State University – Jackson, MS

– University of Puerto Rico – Mayagüez, PR

– Howard University, Washington, DC

University of Oklahoma – Norman, OK

North Carolina A&T, Greensboro, NC (Science & Engineering Camps)

Arizona State University and Arizona Science Center

Museum of Science – Miami, FL

Southwest Florida

Western Kentucky University – Bowling Green, KY

St. Louis University, St. Louis, MO

University of Nebraska – Lincoln, NE

Weather Museum – Houston, TX

Penn State University – State College, PA

Your Chance to Honor Your Colleagues…by Thursday

Time is running out to submit nominations for more than two dozen AMS awards in the atmospheric and related sciences. The deadline for submission is Thursday, 1 May.

Each year the American Meteorological Society seeks the nomination of individuals, teams of people, and institutions for their outstanding contributions to the atmospheric and related sciences, and to the application of those sciences. That means recognition of achievements not only in meteorology but also oceanography, hydrology, climatology, atmospheric chemistry, space weather, environmental remote sensing (including the engineering and management of systems for observations), the social sciences, and other disciplines.

Twenty-five AMS awards, such as the Carl Gustaf-Rossby Research Medal—meteorology’s highest honor—and the Jule G. Charney and Verner E. Suomi medallions, are available to scientists, practitioners, broadcasters, and others. And every year, you, as AMS members, make the nominations and ultimately determine whose amazing achievements to honor with these prestigious awards.

Descriptions of the AMS awards, including links to the nomination procedure, are available on the AMS website. All nominations must be submitted online.

Sharing the May 1 deadline are nominations for AMS Fellows and Honorary Members. The advancement to Fellow is one of the most significant ways the Society honors those AMS members who, over a number of years, have made outstanding contributions in academia, government, industry, and more.

Submitting a nomination takes little of your time but potentially rewards a colleague enormously.

For those nominations we have received and those to be submitted by Thursday, the AMS thanks you.

Awardees and Fellows will be recognized at the 2015 AMS Annual Meeting.

New Honorary Members of the AMS: Qingcun Zeng

Here’s the third of three posts from Xubin Zeng (Univ. of Arizona) and Peter Lamb (Univ. of Oklahoma), who congratulated Robert Dickinson, Brian Hoskins, and Qingcun Zeng for joining them in the ranks of AMS Fellows by asking a few questions by email. This is the interview with Dr. Zeng:

How did you decide to choose atmospheric science or a related field as your profession?

I was born in a peasant family, grew up in the countryside, and personally experienced the strong impact of climate and weather on the agriculture and human life. When I was a student in the Physics Department of Peking University in the 1950s, several meteorological disasters occurred in China, and there was an urgency to develop meteorological service and research. The university and professors suggested us, at least some of us, to study “atmospheric physics”. Thus I chose atmospheric sciences for the future profession. Meantime, the first success of numerical weather prediction was very exciting; therefore I decided to choose numerical weather prediction as my first subject for research.

Who influenced you most in your professional life?

I am very lucky having very kind parents, excellent teachers and supervisors, and many good friends, as they all strongly influence my life. I can’t express how grateful I am to them.

By precept and example, my parents instilled in me the values of fundamental morals and hard work. My teachers, especially Profs. Y.-P. Hsieh, T.-C. Yeh, and E. A. Kibel’, taught me both the research subjects and methodology. Professors Yeh and Hsieh were important members of the Chicago School, while Prof. Kibel’ was a founder of the Petersburg-Moscow School. Their ideas as well as Chinese philosophy converge in my mind, creating new ideas. Professor J. Smagorinsky showed me how to run a research center when I was a visiting senior scientist at the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory (GFDL). Taking this as an example, I established a center of numerical modeling in our institute (IAP/CAS).

Which accomplishments are you most proud of in your professional life?

From a developing country (China), I have been thinking more about how China can learn from and catch up with developed countries in atmospheric sciences. My overall contributions to atmospheric sciences are small. Two pieces are worth mentioning here.

Since 1960s, I have paid special attention to the fundamental physio-mathematical problems, such as the well-posedness of governing equations with proper initial and boundary conditions, the internal consistence of the models written in both the differential and numerical forms, as well as some general features and laws in the rotating fluid dynamics. Some results have been applied to the designs of numerical weather prediction and earth system models in China. These work has also attracted some mathematical scientists to this field.

I have also been gradually involved in the new field of the global change and sustainable development since mid-1980s. I proposed a theoretical framework, the “natural cybernetics”, to try to unify the prediction and regulation of regional atmosphere-environment as a problem of system engineering. This would combine massive observations and practical experiments with mathematical models and numerical modeling. I am looking forward to the future progress in this area by the young generations.

What are your major pieces of advice to young scientists in our field?

Carefully observe and deeply think.

What are your perspectives for future direction of our field?

We have seen the close confluence of atmospheric Sciences and other branches of Earth Sciences with the goals to deeply understand and properly utilize the Earth environmental systems. The weather and climate predictions remain an important subject in the future. In addition, the studies on problems related to planning human activities in order to properly utilize and correctly regulate the natural atmospheric-environmental systems have just started, and should be strengthened.

New Honorary Members of the AMS: Brian Hoskins

Here’s the second of three posts from Xubin Zeng (Univ. of Arizona) and Peter Lamb (Univ. of Oklahoma), who congratulated Robert Dickinson, Brian Hoskins, and Qingcun Zeng for joining them in the ranks of AMS Fellows by asking a few questions by email. This is the interview with Dr. Hoskins:

How did you decide to choose atmospheric science or a related field as your profession?

I never really chose it! After I had started using mathematics to study aspects of dynamical phenomena in the atmosphere it just became clearer and clearer that this combination of a superb system to understand and the practical importance of the subject became more and more what I wanted to continue with.

Who influenced you most in your professional life?

There have been so many it would be invidious to choose one. However, it was Francis Bretherton who started me of on the atmospheric science direction at Cambridge. He gave me the first course I had on applying mathematics to the ocean and atmosphere, had a PhD studentship available on atmospheric fronts, accepted me for it and guided me through the next 3 years.

Which accomplishments are you most proud of in your professional life?

Some of my research highlights; helping the Department of Meteorology at Reading and more recently the Grantham Institute at Imperial develop; my role in the international arena, e.g. WCRP and IAMAS; playing a leading role in the UK in its plans for carbon reduction targets.

What are your major pieces of advice to young scientists in our field?

Enjoy your research. Take a wide interest in the subject and lay the foundation so that you can take the opportunity when it arises to put different strands together in a way no one else has.

What are your perspectives for the future direction of our field?

In my research life atmospheric dynamics has gone from being the tops to being quite out of favour. To make major advances in observing and modeling weather and climate we must develop new frameworks of understanding that focus on phenomena, and the dynamics interacting with the range of physical processes in them.

New Honorary Members of the AMS: Robert Dickinson

Xubin Zeng (Univ. of Arizona) and Peter Lamb (Univ. of Oklahoma) congratulated Robert Dickinson, Brian Hoskins, and Qingcun Zeng for joining them in the ranks of AMS Fellows by asking a few questions by email. Here is the interview with Dr. Dickinson:

How did you decide to choose atmospheric science or a related field as your profession?

When I was a teenager my interests were broad so my interest in science only developed through science courses I took at Exeter and Harvard, and I ended up my undergraduate career with a double major (chemistry and physics). I went into a meteorology program at MIT as a graduate student because I wanted a career more tied to nature. Unfortunately, I stumbled into doing theoretical studies that gave me little opportunity for the field work I had imagined. However, I had no end of opportunities to work on questions of great interest to me which kept me motivated to this day to continue in atmospheric science related research.

Who influenced you most in your professional life?

This is a difficult question as I am grateful to so many people who influenced my professional career. It would be easier to name “the hundred most”. However, in narrowing it down to one, I have to pick my thesis advisor Victor Starr, since his broad interests and approach to scientific research, as a generally enjoyable and relaxing activity, using theoretical reasoning and observations to reveal and interpret basic physical processes, was conveyed to me at a very impressionable age and so had a strong impact on all my future work.

Which accomplishments are you most proud of in your professional life?

I spent much of my career at NCAR, doing many things, and in the early seventies worked with Steve Schneider and others to develop an NCAR climate research initiative, and evolve many of the concepts used today involving climate forcing and feedbacks. That led me a few years later to my learning how to use General Circulation models and to a recognition that their land part was their weakest component, given its overall importance in the system. My consequent efforts to make a better such component model forced me to learn all I could learn about vegetation and leaves. To do this forced me to borrow concepts from many people and learn the need for extensive interdisciplinary activity to be able to make meaningful progress on such a model.

What are your major pieces of advice to young scientists in our field?

Making successful progress in research requires a lot of long hours and hard work so it must be fun for you to put in the effort needed.

Your work will have a much bigger impact if communicated and recognized by many people. You need to write effective papers and to give good oral presentations to have such impact and recognition.

What are your perspectives for future direction of our field?

I think young scientists are better able to answer this than I, so I only suggest a framework: the most important future directions will involve some combination of advancing basic science, responding to societal needs, and employing new technologies. I think at least two of these characteristics are needed for a future direction to be important.