Hurricane Florence is forecast to slow to a crawl as it nears landfall in the next 24 hours. As a result, some unusual and unimaginable things could happen. People in the Carolinas need to take this hurricane seriously. Even veterans of past landfalls there may be in for a surprise.

For starters, slow-moving hurricanes often deliver flood disasters. Think last year’s Hurricane Harvey with its 50- to 60-inch rains. The National Weather Service is predicting widespread rainfall in parts of the Carolinas of 10-20 inches. And some areas could be inundated with 30-50 inches as rainbands spiral ashore and hit spots repeatedly, as they did for days in Texas during Harvey.

Then there’s the storm surge. It may be unprecedented. Sure the Carolinas have endured the likes of Hurricanes Hugo in 1989, Fran in 1996, and Hazel in 1954. All brought storm surges topping 15 feet. But all were also moving quickly. A slowing hurricane like Florence could pile up a lot of water.

If it stalls offshore, says storm surge expert Dr. Hal Needham in a Wednesday blog post, “this will serve to dramatically increase the storm surge magnitude and geographic extent of coastal flooding.”

Already the National Hurricane Center expects some portions of the North Carolina coast to realize surge levels of 9-13 feet. A stalling storm piling even more water onto even more of the coast?

Needham points out an “unthinkable,” seeing that forecast models show “Florence making landfall on Thursday evening…and Florence still making landfall on Friday evening. A slow-moving hurricane tracking near a coastline is bad news indeed, as it enables the storm to inflict destructive storm surge along an extended area.”

What’s worse is that the collapsing steering currents may not just delay landfall but also could lead to the hurricane drifting southwest with its core paralleling the South Carolina coast. Initial offshore winds that are increasing as the center moves closer to any point on the coast would drive water ashore in ways unseen in other landfalling hurricanes. Intracoastal waterways could flood barrier islands on their landward sides, and previous precautions for flooding may not be sufficient.

A recent example is 2017’s Hurricane Irma flooding coastal Jacksonville, Florida. When landfalling storms approach Jacksonville from the Atlantic Ocean, winds initially blow from north-to-south. But Irma’s huge wind field instead whipped up a coastal surge from the south, swamping places unaccustomed to surge.

But Florence’s surges may be more than a directional oddity. The hurricane’s offshore winds will initially push tremendous amounts of water away from the coast, much like offshore winds emptied Tampa Bay, Florida as Irma approached. As Florence’s center then passes, Needham explains, “powerful winds in the hurricane’s eyewall, the most intense part of the storm, would immediately shift from offshore to onshore, producing a destructive storm surge in the matter of minutes.” Such sudden, extreme changes are likely to catch residents off guard.

It happened recently in The Philippines. Supertyphoon Hainan’s surge came ashore like a tsunami, Needham says, as the wind shifted direction. He notes that 2013’s Hainan was one of the most intense tropical cyclones to make landfall in recorded history, and he doesn’t expect the surge from Hurricane Florence to move as rapidly.

Still, such a sudden reversal of high winds from a hurricane moving unusually from north to south off the South Carolina coast would push storm surge quickly ashore, devastating the shoreline.

Expect the unexpected with Hurricane Florence. If local authorities tell you to leave, get out.

Media Tips

Time Machines, Horse Ploppies…Richard Alley Will Do the Talking Today

From his book and PBS-TV series, “Earth: The Operator’s Manual,” to his renowned lectures at Penn State, Dr. Richard Alley is known for his humorous descriptions about serious science. Today he is the featured speaker as the 98th Annual AMS Annual Meeting begins in Austin, Texas.

At the 18th AMS Presidential Forum (4 pm, Ballroom D) Dr. Alley will use his unique brand of communication to discuss why communicating science to the public is no longer optional, but rather an imperative.

Dr. Alley, a renowned glaciologist and climate scientist, has a way with words. His colorful metaphors–like The Two-Mile Time Machine, the title his award-winning popular book about ice cores–put complex scientific issues into a comfortable perspective for perplexed audiences.

Last May, a couple months before a large piece of Antarctica’s Larson C ice shelf broke off, Rolling Stone published an article about potential catastrophic collapse of West Antarctica ice. In it, Dr. Alley explained that the Larson C breakage would not necessarily be an “end-of-the-world screaming hairy disaster conniption fit.”

And here, transcribed from a 2012 talk at the Smithsonian in which Dr. Alley explained the impact of burning fossil fuels and releasing CO2:

“You fill up a car and it’s a fairly big tank–you’re putting in a hundred pounds of gasoline. If you had to bring it home in gallon jugs it’d be a different world. But you drive off with it. And when you burn it — you add oxygen — and that makes CO2, and it goes out the tailpipe and you don’t see that 300 pounds per fill-up. Now, our students really get a kick out of it: at this point you say okay, suppose that our transportation system packaged the CO2 in a way we could see it … as horse ploppies…It’s a pound per mile driven for a typical vehicle in the fleet at this point. Ya know … Nnnnn — thffft. Nnnnn — thffft …. Our CO2 turned to the density of horse ploppies and spread over the roads of America would cover every road in America an inch deep every year. On average. Okay. In a decade … there are no joggers. We’d all be cross-country skiers. If we saw this it would be a completely different world. But it just drifts away and we don’t even see it.”

Sunday’s keynote talk at the Presidential Forum is likely to be just as, ummm, vivid. Simple but powerful. Definitely memorable.

It’s exactly the way Alley envisions engaging the public: by building the broad understanding necessary to make science actionable.

Science for Oysters…and Oysters for Scientists

One of the highlights of New Orleans is its distinctive, world-renowned cuisine. And indulging in that famous cuisine more often than not means enjoying the bounty of the Gulf of Mexico. AMS members will descend on New Orleans right at the high season for oysters, according to food critic Brett Anderson writing in the local paper, the Times-Picayune, right before Christmas:

Meteorologically speaking, it is an inconvenience that Louisiana oysters are never more delicious than they are right about now, just as we’re growing accustomed to the daily threat of something resembling winter. Wouldn’t it be nice if oysters were at their crispest in August instead, when they could provide cool relief from the blood-hot sun? Yes, that would be nice, but our reality is pretty sweet as well: oysters at their peak, tasting like clean ocean water, firm-fleshed and sitting pert on their shell. They’re perfectly sized, large enough to announce their presence, small enough to swallow whole. Get another dozen. It’s gift-giving season.

According to the reports from the restaurants, the local crop is back to the quality seen before the big BP Horizon oil spill of 2010. Prices and supplies have normalized.

So while you’re hunting for some Gulf oysters on the half-shell later this month at the AMS Annual Meeting, keep in mind that this delicacy is not only featured on your plates but, also, featured on scientific program. In particular, two presentations might ease concerns you have about subjecting your stomach to the raw variety (of food, not science, of course!). Gina Ylitalo (NOAA) and colleagues will present on “Oil Spills and Seafood Safety” (8:45 p.m., Tuesday, Room 333). They write

Thousands of seafood samples collected during reopening and surveillance in the Gulf, as well as those obtained dockside and in the marketplace have been analyzed using [advanced] analytical methods. While chemical compounds associated with the oil spill have been detected in seafood samples using these various analytical methods, none were present in edible tissues at levels that approached levels of concern for human consumers of seafood products from the Gulf.

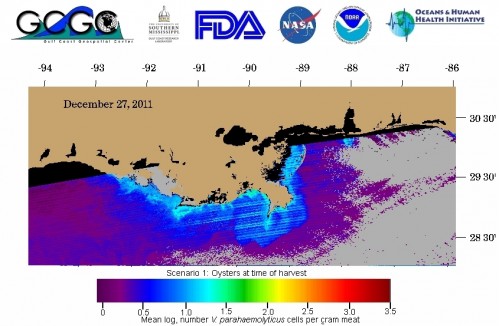

Later in the same session on Tuesday, Jay Grimes (Univ. of Southern Mississippi) will talk about monitoring disease potential from raw seafood with satellite monitoring of ocean temperatures and salinity, in “Can You Really See Bacteria from Space?”. Below is the latest bacteria estimate from their oceanographic monitoring website:

The Hazards of the Winter Roads

- 17% of all fatal accidents and 7,130 persons are killed in weather-related accidents each year.

- The Midwest has the greatest average intra-annual variability for both trucks and passenger vehicles. For large commercial trucks, the average monthly peak occurs in January with 38.29% of accidents occurring with adverse-weather, and a minimum in June of 8.27%. For passenger vehicles, accidents are less affected by adverse-weather with an average intra-annual peak of 30.28% in January and a minimum of 6.32% in June.

- The South has the least average intra-annual variability of accidents in adverse-weather.

- Adverse-road related accidents are greater in all regions than adverse-weather due to the fact that accidents can occur on wet or snow/ice covered roads in the absence of adverse-weather.

Cool Roofs Seen in Black, White, and Green

Science teaches us not to answer questions in black and white terms—the meaning of data usually has many shades of gray. So it is with figuring out the micro and macro effects that different roof coverings might have on global warming or energy efficiency. The answers are starting to look more complex, and more promising, than ever.

For example, it would seem natural when studying rooftops and their effects on climate large and small to focus on extremes of albedo—in other words, black and white surfaces. This is sometimes the case in simplified modeling studies. But at this week’s AMS 9th Symposium on Urban Environment, in Keystone, Colorado, Adam Scherba of Portland State University submitted findings that moved beyond simple comparisons of white (“cool”) roofs versus black roof coverings. He and his colleagues mixed roof coverings, notably photovoltaic panels and greenery (which has the advantage of staying cooler during the day but not, like white roofs, getting much colder at night). The mix makes sense when you consider that roofs are also prime territory for harvesting solar energy. Scherba et al. write that

While addition of photovoltaic panels above a roof provides an obvious energy generation benefit, it is important to note that such systems – whether integrated into the building envelope, or mounted above the roof – can also result in an increase of convective heat flux into the urban environment. Our analysis shows that integration of green roofs with photovoltaic panels can partially offset this undesirable side effect, while producing additional benefits.

This neither-black-nor-white-nor-all-green approach to dealing with surface radiation makes sense from both energy and climate warming perspectives, especially given the low sun angles, cold nights, and snow cover in some climates. For instance, a recent paper, in Environmental Research Letters, uses global atmospheric modeling to estimate that boosting albedo by only 0.25 on roofs worldwide—in other words, not a fully “cool” scenario of all white (albedo: 1.0) roofs—can offset about a year’s worth of global carbon emissions.

And the authors of a recent modeling study (combining global and urban canyon simulation) published in Geophysical Research Letters simulated a world with all-white roofs but showed that:

Global space heating increased more than air conditioning decreased, suggesting that end-use energy costs must be considered in evaluating the benefits of white roofs.

Delving directly into such costs this week at the AMS meeting is a paper from a team led by Anthony Dominguez of the University of California-San Diego. They looked at the effects of photovoltaic panels on the energy needs in the structure below the roof, not the atmosphere above it.

Did they find that a building is easier to keep comfortable when covered by solar panels? Well, if you need to air-condition during the day, yes. If, however, like many people on the East Coast this summer, you need to keep cooling at night, then no. This is science—don’t expect a black-and-white answer.

Counting the Cards in Nature's Casino

With “New Demands on Science and Services” being the theme of this AMS Annual Meeting in Atlanta, it is safe to say that no demand on climate science is more novel and complex than the national security angle of climate change. Strife in Africa is one area, as we mentioned here, but other flash points include the security of borders once covered by glaciers, water scarcity in numerous regions, and the newly navigable Arctic waterways.

It’s no wonder the Oceanographer of the Navy has gotten involved in this new area. Rear Admiral Dave Titley, oceanographer of the Navy, who has been charged with the U.S. Navy Task Force Climate Change, will be one of several national security experts featured in the two-part Tuesday Joint Session panel discussions (11 a.m. and 1:30 p.m.) on “Environmental Security: National Security Implications of Global Climate Change.”

In an interview on climate change with Armed Services radio, Admiral Titley showed a strikingly forward, mission-oriented viewpoint on the Navy’s interest in climate change, and not just the practical attitude of an officer with a research background.

“We’re operating in Nature’s casino,” he said, “and I intend to count the cards.”

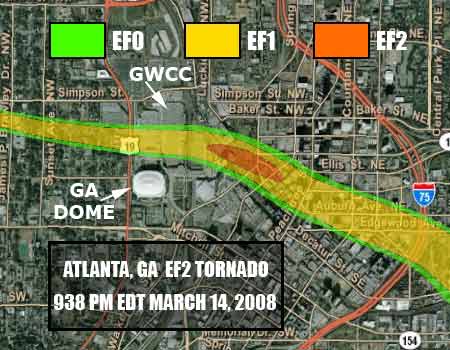

Atlanta Tornado and Impacts: Weather 2009

In the evening of March 14, 2008, the Georgia World Congress Center where the 90th Annual Meeting of the AMS is taking place this year was hit by an EF2 tornado. The supercell thunderstorm that produced the tornado was unexpected that day, with an outbreak of tornadoes forecast for, and subsequently realized, the next day.

The adjacent Omni Hotel as well as CNN Center and a number of nearby hotels and buildings suffered significant damage in the tornado. CNN Center alone lost more than 1600 windows, and windows are still missing in the tube-shaped Westin Peachtree Plaza tower.

CNN was not broadcasting live from Atlanta that night with programming instead coming from its New York and Washington offices. If the 24-hour network had been live from CNN Center, “It could have been a classic You Tube moment,” says Brandon Miller, a weather producer for CNN International, adding, with “us in the center of the tornado, anchors looking all around, fear on their faces … Fortunately, that didn’t happen.” Miller says CNN didn’t cover the tornado strike itself live, but “covered the heck out of the damage afterwords.”

While this tornado event won’t be presented as part of Impacts: Weather 2009 at the 2010 AMS Annual Meeting, a presentation during this Tuesday session will look at Tornado Effects on a Rural Hospital: Impacts of an EF-3 Tornado that struck Americus, Georgia in March 2007 (2:00 PM, January 19, 2010, B206). A presentation Wednesday morning (9:15 AM, B217) will look at lightning characteristics of the Georgia tornado outbreak the day after the 2008 Atlanta tornado. Its author commented that lightning characteristics of the tornadic storm that struck Atlanta the previous day might also be presented, if time allows.

Also, a poster to be presented Monday will investigate the relationship, if any, between Southeastern tornadoes and drought. A climatological analysis of antecedent drought and spring tornadic activity will be available for viewing during the poster session Observed and Projected Climate Change from 2:30 – 4:00 PM Monday, January 18.

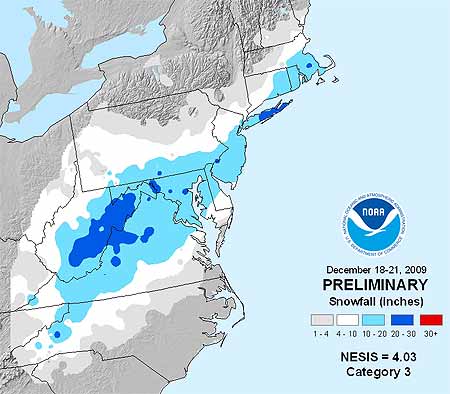

December East Coast Snowstorm a Cat. 3

Memories of the pre-Christmas snowstorm that paralyzed travel across megalopolis in mid December might not be as fresh as the severe cold snap that kicked off the new year east of the Rockies. But the storm, which dumped 1-2 feet of snow on the Mid-Atlantic, earned a Category 3 ranking on the Northeast Snowstorm Impact Scale, known as NESIS, classifying it as a “major” winter storm.

NOAA’s NESIS ranks Northeast snowstorms on a five-tier scale ranging from Category 1 “Notable” to Category 5 “Extreme.” It characterizes the storms based on how much snow falls (must deposit at least 10 inches); the size of the area affected, and the population of the impacted area. Developed in 2004 by renowned winter weather experts Louis Uccelini and Paul Kocin, both with the National Centers for Environmental Prediction, catalogs snowstorms dating back to 1888.

“Last month’s storm was one of only five in the past decade that ranked Category 3 or higher,” says Kocin. The others: December, 2002 (Category 3); February, 2003 (Category 4); January, 2005 (Category 4); February, 2006 (Category 3), and February, 2007 (Category 3). Topping the NESIS scale—and the only winter storms rated Category 5—are the “Superstorm” on March, 1993 and the “Blizzard of ’96” in January, 1996. Last month’s snowstorm fell short of the higher NESIS rankings for several reasons, explains Uccelini.

“While snowfall from the December storm ranked in the top ten for Washington, Baltimore and Philadelphia, the storm only provided a glancing blow to the New York City and Boston metropolitan areas and overall affected a relatively small area. This led to it being classified as a Category 3,” he says.

Although NESIS is the only snowfall index being used operationally by NOAA, there are NESIS-like indices being developed for other parts of the nation. At the AMS Annual Meeting in Atlanta, a presentation by Michael F. Squires (Wednesday, 20 January, 2:00 PM, B211) will discuss the Development of regional snowfall indices.

Addtionally, David Robinson of Rutgers University will introduce a new climate data record of satellite-derived snow cover extent in his presentation Northern Hemisphere snow cover extent during the satellite era (Wednesday, 20 January, 10:30 AM, B218).

A Minimum of Maximum Concern

There are a lot of questions about the current solar minimum, which has reached historic levels—“No solar physicist alive today has experienced a minimum this deep or this long,’’ according to NASA’s Madhulika Guhathakurta, lead program scientist for NASA’s Living With A Star program, which studies solar variability and its effects on Earth. Some of the effects of the minimum are fairly clear to scientists: the amount of cosmic rays entering our portion of the solar system is greater than normal, and Earth’s ionosphere has shrunk.

The debate is instead partly about the effect of the minimum on Earth’s climate. A recent study by Judith Lean of the Naval Research Lab and David Rind of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies suggests that decreased solar irradiance during the current minimum cycle may be slightly offsetting recent warming attributed to greenhouse gases. Even if the minimum is affecting climate, it may be of minimal consequence.

“. . . [O]nly about 10 percent of climate variation is due to the sun,” notes Leon Golub, senior astrophysicist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Institute for Astrophysics. “That means 90 percent isn’t.”

Just as importantly, the solar minimum won’t last forever, so any climatic effects are temporary, as well. But when will solar activity turn around? The current minimum began in 2000 and has been particularly deep for the last two years. At the AMS Annual Meeting, Joseph Kunches of NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center attempts to pinpoint the arrival of the next solar maximum and ponders its potential effects in his presentation, “Solar Cycle Update—Will the New Cycle Please Start?” (Monday, 2:15–2:30 p.m., B303). And Matthew J. Niznik and W. F. Denig of the National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service introduce a new indicator, the Genesis Minimum Quiet Day Index, which analyzes sunspot activity and suggests that the current solar minimum is not anomalous. Their index and the larger topic of the influence of solar activity on Earth’s climate are explored in their poster, “Impacts of Extended Periods of Low Solar Activity on Climate” (Monday, 2:30–4:00 p.m., exhibit hall B2).

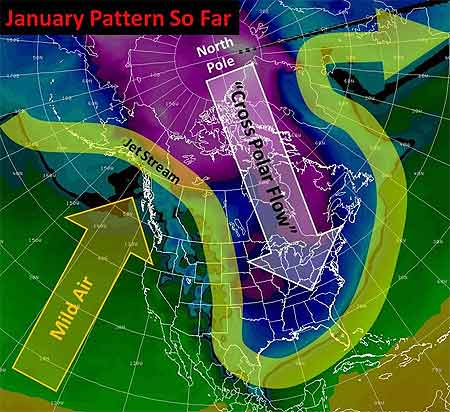

Harsh Cold Wave Slowly Retreating

Well, the big winter cold snap that has been gripping much of the United States since December is nearing its end. Temperatures in most places from the Plains to the East Coast have started to rebound and no renewed surges of Arctic air are on the horizon after a final weak front moves through the East Tuesday. But the damage is done in places from the Dakotas and Montana to Florida: burst pipes, roads that drifted shut, and wind chills lower than -50 in the North, and car crashes on icy roads, power outages, and record cold that has chilled the South.

Last Thursday, the wind chill in Bowbells, North Dakota hit 52° F below zero. That degree of cold “freezes your nostrils, your eyes water, and your chest burns from breathing — and that’s just going from the house to your vehicle,” said Jane Tetrault of Burke County. Her vehicle started, but the tires were frozen. “It was bump, bump, bump all the way to work with the flat spots on my tires,” she said, adding, “It was a pretty rough ride.”

Snow and icy winds whipped southward from the Midwest into Tennessee, Georgia, and Alabama late in the week, making travel a disaster in Memphis and Atlanta. Video of cars sliding off roads or into each other played every half hour on The Weather Channel into the weekend.

Even the Sunshine State had wintry precipitation with this unusual cold surge—something not seen in more than 30 years. The weekend into Monday was especially brutal by Florida standards. With temperatures in the 30s and low 40s, light rain enveloped the peninsula Friday night through Saturday. Sleet fell in spots from Jacksonville and Ocala southward through Orlando, Tampa, and Melbourne into Palm Beach. A few wet snowflakes mixed in here and there with snow reported by trained spotters as far south as Kendall, a southern suburb of Miami. In some places north of Tampa, enough sleet accumulated on cars and outdoor furniture to build little “sleet” men, complete with tiny hats and tree-twig arms, their photos rivaling those taken of snowmen built in Tampa on January 17, 1977. (View a of Florida sleet from a snow and ice slideshow on Tampa’s baynews9.com.)

Clearing led to record morning lows both Sunday and Monday that threatened harm to Florida’s $3 billion citrus industry. Temperatures bottomed out at 25° in Tampa, 29° in Orlando, and 31° in Ft. Myers. On Sunday, the temperature in Miami tied the 1970 record for the date with 35°, and a 36° low Monday morning broke the previous record for the date of 37° set in 1927. Despite the records, it has been the duration of the cold, especially in the South, that makes this cold snap memorable. Morning after morning since the previous weekend, photos of Florida strawberries encased in ice showed up on newscasts. Such protective measures against the frigid temperatures are expected for several more mornings in central Florida, even as the chill slowly moderates.

The cold was even long-lasting in the Midwest and Plains, as noted in TWC meteorologist Tim Ballisty’s article “It’s Cold But So What?” last week. He points out that Chicago hasn’t been above freezing since Christmas Day, at the time 11 straight days and counting. Cleveland had 10 consecutive days of snow, and that count continued right into the weekend.

Unlike the extensive heat waves of recent summers, this long and harsh cold snap resulted in relatively few new temperature records. At the Annual Meeting in Atlanta, Gerry Meehl of NCAR will explore the rising ratio of record high temperatures to record low temperatures, which is expected to markedly increase by the middle of the century with current projections of climate warming.