A 2024 AMS Summer Community Meeting highlight

The AMS Weather Enterprise Study will provide a comprehensive picture of the shifting landscape of weather-related fields to inform our joint future. At the 2024 Summer Community Meeting, working groups discussed what they’d found about key issues facing the enterprise.

Here are a few takeaways from the Community Modeling working group, as reported by Gretchen Mullendore of the NSF National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR). Community modeling employs Earth system model software developed by public-academic partnerships. Community models have open-source components and are freely available for use by anyone with the computing power to run them–for example researchers, students, and private companies.

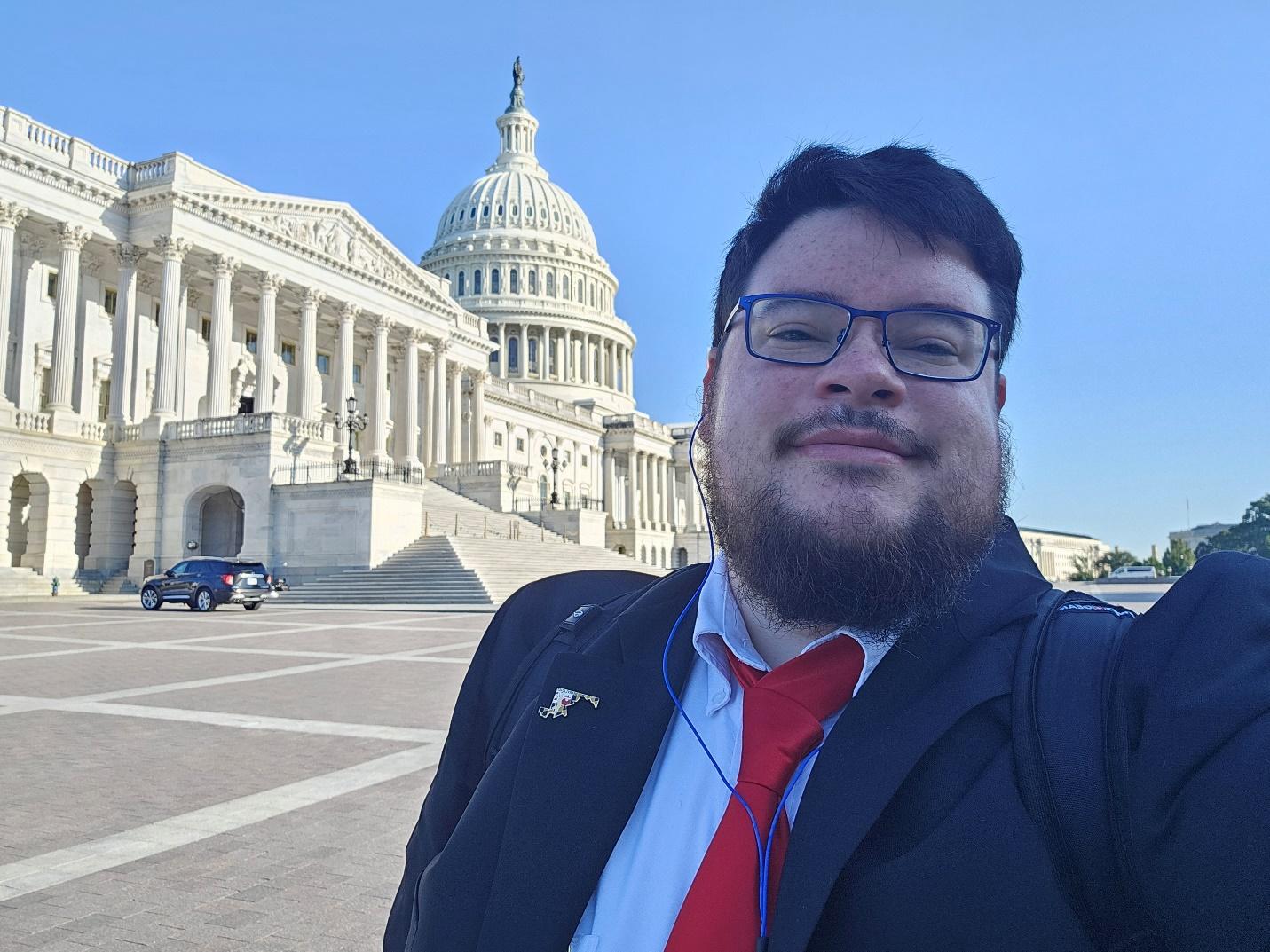

Photo: Gretchen Mullendore

How has the community modeling landscape changed in recent years, and where are we now?

First, artificial intelligence and machine learning (AI/ML) have become huge players in numerical weather prediction (NWP) model development. Second, a cultural change in weather research and forecasting is taking place; we’re beginning to collaborate much more closely across agencies and industries than we used to, and many people are invested in deepening those collaborations.

What were the main themes that came out of your working group’s discussions?

The NWP community is collaborating more than ever before. However, the community remains spread among many institutions, with each research group working on small pieces of the overall weather prediction challenge. Having many research groups can be a strength in terms of encouraging innovation, but it is a weakness if research isn’t coordinated effectively to fully realize collective benefits. Limited funding and resourcing is an additional barrier to community model development. As a community, we need to continue to prioritize modularity and interoperability across NWP systems and work towards more effective shared governance.

Another major theme is the role of the private sector in NWP. Big tech companies are increasingly getting into NWP and there is a concern that public forecasting efforts are not able to keep pace. The private sector brings agility and innovation to the field, and working to leverage unique contributions across public, academic, and private research entities is valuable. However, if the growing role of the private sector in NWP leads to more observations, simulations, and software being behind proprietary walls, there is risk to accessibility and collaboration.

The NWP community is also facing challenges in workforce development. Universities are teaching people the right skills to work in data assimilation and analytics, but many of those people are being scooped up by private sector companies in other fields offering salaries that employers in the weather industry cannot compete with. We need to better communicate the value of our missions and our work to attract and retain talented early career professionals.

What preliminary recommendations or future directions have you discussed?

We can and should continue to build on community efforts to coordinate across public, academic, and private developers. This coordination should include planning for the appropriate use of AI/ML tools in NWP research and applications. We can also build on efforts to leverage social science research to prioritize our limited resources, e.g., by learning what type of forecasting improvements will most benefit stakeholders. Finally, we need to recognize the importance of the legislature in resourcing model development. It’s important to communicate our successes and the value of a thriving NWP community. In summary, we should strategize to develop intentional communication among ourselves, across disciplines, and most importantly, with legislatures and the public.

What did you hear from the community at the Summer Community Meeting?

My pick for the most important question asked at the SCM is, “What does success look like in NWP development?” The goal that motivates us all in the NWP community is for no more deaths to occur as a result of weather hazards. In order to achieve breakthroughs in prediction that stand to move us closer to that goal, we need to invest in innovation, which requires risk. However, much of the work in NWP development is funded by federal agencies, which tend to be risk-averse. More broadly, the systems in which our scientists work can be an impediment to innovation. For example, the pressure to publish often incentivizes incremental progress over new ideas. Collectively, as an NWP community, we need to build systems that allow researchers to take risks without fear of failure or negative consequences.

What are the main challenges, conflicts, or points of discussion identified by the group (or at the SCM)?

AI/ML could possibly improve the skill and speed of all parts of the NWP system. That said, the challenges are also great. Challenges include a lack of AI/ML expertise in NWP community leadership; a need to invest in AI/ML without additional resources; and a need to keep up with the latest AI/ML research, which is moving incredibly rapidly. The lack of clear AI/ML plans from U.S. institutional leaders in NWP led some to ask at the SCM if leaders were skewed against it. My perception is instead that the community is feeling overwhelmed by these challenges. We can overcome these challenges through innovation and collaboration, leveraging our respective expertise and investments to more efficiently take advantage of the great opportunity that is AI/ML in NWP.

Want to join a Weather Enterprise Study working group? Email [email protected].

About the Weather Enterprise Study

The AMS Policy Program, working closely with the volunteer leadership of the Commission on the Weather, Water, and Climate Enterprise, is conducting a two-year effort (2023-2025) to assess how well the weather enterprise is performing, and to potentially develop new recommendations for how it might serve the public even better. Learn more here, give us your input via Google Forms, or get involved by contacting [email protected].

About the AMS Summer Community Meeting

The AMS Summer Community Meeting (SCM) is a special time for professionals from academia, industry, government, and NGOs to come together to discuss broader strategic priorities, identify challenges to be addressed and opportunities to collaborate, and share points of view on pressing topics. The SCM provides a unique, informal setting for constructive deliberation of current issues and development of a shared vision for the future. The 2024 Summer Community Meeting took place August 5-6 in Washington, DC, and focused special attention on the Weather Enterprise, with opportunities for the entire community to learn about, discuss, debate, and extend some of the preliminary findings coming from the AMS Weather Enterprise Study.