The success of the D-Day Invasion of Normandy was due in part to one of history’s most famous weather forecasts, but new research shows this scientific success resulted more from luck than skill. Oft-neglected historical documentation, including audio files of top-secret phone calls, shows the forecasters were experiencing a situation still researched and practiced today: “decision-making under meteorological uncertainty.”

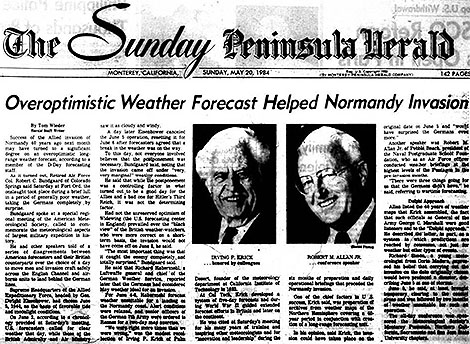

New research recently published in BAMS into that weather forecast for June 6, 1944, which enabled the Allies in World War II to gain a foothold in Europe, answers questions about three popular perceptions: were the forecasts, which predicted a break in the weather, that good? were the German meteorologists so ill-informed, missing that weather-break? and was the American analog system for prediction so great and better than what the Germans had?

The “alleged” weather break

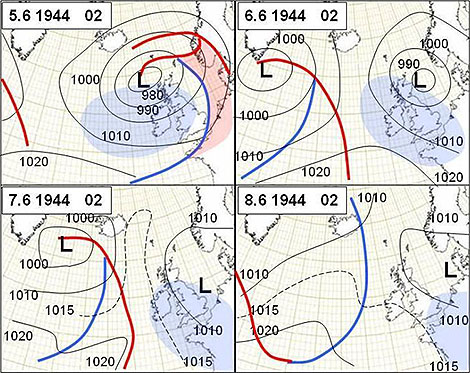

An expected ridge and fair weather between two areas of low pressure, one departing and one arriving over the area, didn’t materialize. The departing low instead lingered and created a lull in visibility and lifted the cloud ceiling height, but it didn’t slow winds much. They blew at Force 4-5 (~13-24 mph), creating very choppy seas that sickened many troops prior to the invasion.

A blown German Forecast?

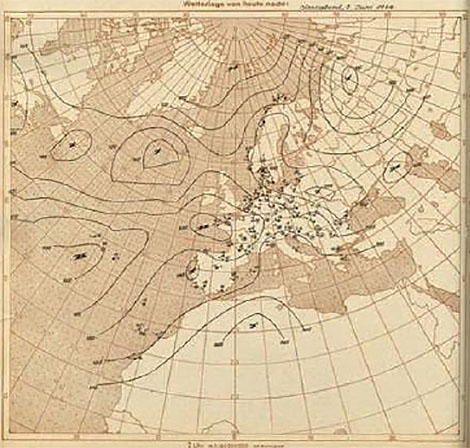

Because the invasion came as a complete surprise to the Germans it has been surmised their weather forecast for June 6 had to be bad. German forecasters prior to the war were the best at “extended” forecasts, and their synoptic maps and forecast for that day were more realistic than the Allies, with a less optimistic speculation of any break in the weather.

A historically debated forecast

The analog weather prediction system employed by the Allies for the invasion was claimed by its creators to have correctly identified the weather break. But historical analysis and review doesn’t bear this out. What it does find, though, is that the system correctly identified a transition from zonal to meridional flow, which delivered the break the Allies needed for success. History’s finding: The forecast was “Overoptimistic.”

As a lesson learned from this most famous of weather forecasts, the paper’s author, Anders Persson of Swedin’s Uppsala University, concludes:

It was 75[+] years ago and the observational coverage has improved tremendously since then, both qualitatively and quantitatively. Our understanding of the atmosphere is much better,and the forecast methods have reached a standard that could hardly have been dreamt of in 1944. However, there’s one element that has a familiar ring to it and is of great interest today. That is when Air Marshall Tedder [Deputy Supreme Commander of the Invasion under General Eisenhower] asks about an assessment of the confidence in the forecast he has just heard … This illustrates that the D-day forecast is a significant early example of decision-making under meteorological uncertainty.