By Mary M. Glackin, AMS President-Elect, and Dr. Joel N. Myers, Founder and CEO, AccuWeather

In his acclaimed book, The Signal and the Noise, noted statistician Nate Silver examines forecasts of many categories and finds that most forecast types demonstrate little or no skill, and most predictive fields have made insignificant progress in accuracy over the past several decades. The one exception, Silver concludes, is weather forecasting, which he singles out as a “success story.” We quite agree.

The benefit of improved weather forecasting on human activity over the last 60 years cannot be overstated. As we approach in January the 100th Annual Meeting of the American Meteorological Society, the nation’s premier scientific organization dedicated to the advancement of meteorological science, it seems a fitting time to celebrate all that we have accomplished for the protection of life and property and the substantial benefits to people and business and contemplate the challenges ahead and the path forward to conquer them.

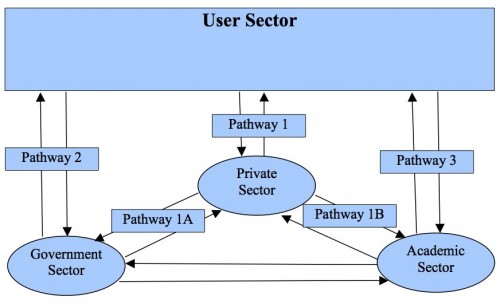

With technology and human knowledge increasingly transforming both weather forecasting and our relationship with it, our success will rest squarely on our ability to embrace transformational change and to recognize and welcome opportunities for collaboration between key facets of the weather enterprise – academic, government and the private weather industry.

The publicly funded National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration plays a critical role in supporting the entire infrastructure of weather forecasting, which government organizations, such as the National Weather Service, the U.S. military, and privately held organizations rely on. This infrastructure includes observational systems, maintenance and support of numerical weather prediction models, and providing life-saving weather warnings. Warnings, arguably, are the biggest payoff of weather forecasting with lives and property on the line.

The NWS analyzes and predicts severe weather events and issues advisories and warnings to the general public for their safety and protection. Warning services provided by NWS have improved over the decades. By design, NWS weather warnings cover a broad territory, intended for the widest possible public audience in a region.

While all government weather warnings reaching the public are produced by the NWS, increasingly in today’s digital age they are tailored and delivered almost entirely by private weather providers through news broadcasts and free, advertising-supported mobile phone apps and other digital sources of convenience. The greatest challenge the weather enterprise faces is ensuring these life-saving weather warnings reach the greatest number of people potentially impacted by hazardous weather with enough advance notice to take proactive steps to remain safe and out of harm’s way. When seconds count in a weather-related emergency, this partnership example significantly extends the reach of the government for greater public safety.

What some may not realize is that when severe weather threatens, companies, such as AccuWeather, pair a deep understanding of client operations with their team of meteorologists to provide vital services, such as custom site and operation specific weather warnings, to clients tailored to their risk thresholds.

A recent Washington Post article mistakenly conflated warning services provided by NOAA with custom warning services provided to private clients.

In fact, with example after example, there is no doubt private companies, such as AccuWeather, which has received many AMS accolades for its warnings and expertise, can and do provide valuable warnings and services to private clients. It was unfortunate that a comment said on the fly was taken out of context. Both AccuWeather and AMS view the incident in this light and are continuing to build on their shared history of partnership. AccuWeather works closely with NOAA and NWS to make sure communities and businesses have the best information and warnings they need to stay safe. This partnership has never been stronger.

In fact, there has been a long history of cooperation between the public and private weather sectors. National Meteorological and Hydrological Services (NMHS), including the NWS, readily source data and intellectual property from private companies to support their mission of saving lives, protecting property, and enhancing the national economy. This trend is likely to continue in the world of shrinking government budgets and resource allocation. In turn, private companies leverage technologies, such as the many forecast models provided by NMHS, as the foundation to their own products and services.

As we look ahead to the next 100 years, many challenges impacting the future of the weather enterprise loom large, such as cost and financial pressures, the hyperbolic increasing rate of the capture, storing, processing and analyzing of data, emerging challenges of health and climate change and new accelerating technologies and platforms in the digital age, some of which we cannot yet even conceive.

These sectors of the weather enterprise have their own advantages and efficiencies and together we can most certainly succeed in furthering meteorological advancement if we capitalize on each other’s strengths and work cooperatively and decisively to achieve our larger mission of safety and protection.

All partners in the weather enterprise –government, commercial and academia — in addition to the support and stewardship of important professional organizations, such as the AMS, the National Weather Association and the American Weather and Climate Industry Association – are essential to meteorological progress, and the sum of our value to the public and business can be far greater than the individual parts.

In the last six decades, each component of the weather enterprise has learned to better understand and appreciate one another and to communicate more effectively and to respect the important contributions of each in the true spirt of cooperation. The greatest example of this is the AMS-championed Fair Weather Report, a study funded by the federal government to generate more harmony across the entire weather enterprise.

Since we began our careers, we have had the privilege of seeing amazing progress in our ability to provide more specific, more accurate, and more useful weather forecasts and warnings, which extend further ahead and have saved tens of thousands of lives and prevented hundreds of billions of dollars in property damage.

With even more and better collaborations between the various facets of the weather enterprise, there is no question the public and our nation stand to benefit from greater safety and better planning. We look forward to continuing our work together to bring about more exciting innovations and enhancements to advance public safety.

Editor’s note: Mary M. Glackin is President-elect, American Meteorological Society. She was formerly the Deputy Under Secretary for Oceans and Atmosphere at National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and a Senior Vice President of Science and Forecast Operations at The Weather Company (IBM). Dr. Joel N. Myers is Founder and CEO of AccuWeather