For the third year in a row, the AMS Symposium on Building a Weather-Ready Nation (AMSWRN) will host its highly successful, highly interactive “WRN Asks: What If?” session to kick off its program at the AMS 105th Annual Meeting. “WRN Asks: What If…?” takes place at 8:30 a.m. CT on Monday, 13 January, 2025. We spoke to Trevor Boucher, AMSWRN co-chair, about why this session is unique, and why AMS attendees from all disciplines should take part. To learn more about this session and its origins, read our spotlight post from the 104th Annual Meeting.

Why host an interactive session like this?

Trevor: We want our audience to be interacting and collaborating when they all get in the same room once a year. What are those elephant-in-the-room topics that are larger in scale and scope than a single research project or study? More importantly, what are the implications of those topics?

Since 2013, AMSWRN has brought together meteorologists and other Weather, Water, and Climate Enterprise partners to discuss efforts in advancing what it means to be “Weather-Ready.” We have hosted oral presentations, posters, panels, town halls, and more. But the Weather Ready Nation initiative is about changing how society looks at the weather every day, and how our nation thinks and responds to the environment around us. We are talking about evolving the entire weather paradigm, which means we really need to engage with our stakeholders. This in turn means we have to ask ourselves three crucial questions when it comes to learning and getting input: are we doing things right? Are we doing the right things? And how do we even know what is right? That is why the WRN Symposium will open with the 3rd iteration of a special, interactive session, “WRN Asks: What If…?” which goes beyond the normal conference formats to really get people thinking and facilitate discussion.

What are your goals for the session?

Trevor: The session design fits into a transformative learning model, which we published in the August 2024 issue of Bulletin of the AMS with the encouragement of Dr. Justin Sharpe, one of our first “What If…” session leaders. We aim to understand the forces shaping our sciences, and explore how the enterprise may evolve depending on what changes and what stays the same.

We hope to achieve two main goals: 1) inspire the audience, especially the students in attendance, to keep the “big-picture” in view and encourage double and triple-loop thinking, and 2) inform our call for papers in future years with special sessions called “What Now?” in which we explicitly solicit abstracts in the realm of the previous year’s “What if…” discussions.

What’s in store for attendees at the 2025 session of “WRN Asks: What If…?”

Trevor: We designed this session as a “reverse panel”, where moderators provide a 3-5 minute “state of the science” with respect to their backgrounds and propose an open-ended, “What if…?” question to the audience. Then their role shifts to moderating audience discussion for the remainder of their time slot. So although you see specific speakers on our agenda, they do the least amount of the speaking. The audience are the true panelists, sharing their opinions, their knowledge, and their concerns about these questions. We also make sure to get as much input as possible from students and early career professionals.

Last year’s session was extremely successful, with 60-80 attendees and very active discussions. This year—because we kept having to cut off the discussions last time around!—we have reduced the number of questions to three, to give each question a little more discussion time during our 90-minute session. We have also partnered with the 20th Symposium on Societal Applications: Policy, Research and Practice and the 13th Symposium on the Weather, Water, and Climate Enterprise as a Joint Session this year. Each participating symposium is contributing one “What if…” question and speaker to the discussions. The questions include:

“What if…we never issued weather warnings?”

Dr. Danielle Nagele (NWS Social Scientist)

“What if…social media was suddenly banned?”

Devon Lucie (Broadcast Meteorologist, WDSU New Orleans)

“What if…all weather observations didn’t suck?”

Garrett Wheeler (Campbell Scientific)

I’ve been on all our coordination calls and dry runs and we have had to cut short our own conversations each time because we just can’t help but discuss these important questions — and that’s just 6-7 of us. I really think AMS attendees will find it to be an invigorating way to begin their week in New Orleans.

About the AMS 105th Annual Meeting

The American Meteorological Society’s Annual Meeting is the world’s largest annual gathering in the weather, water, and climate spheres, bringing together thousands of scientists, other professionals, and students from across the United States and the world. Taking place 12-16 January, 2025, the AMS 105th Annual Meeting will highlight the latest scientific and professional advances in areas from extreme weather to environmental health, from cloud physics to space weather and more. In addition, cross-cutting interdisciplinary sessions will explore the theme, “Towards a Thriving Planet: Charting the Course Across Scales.” The meeting takes place in New Orleans, Louisiana, at the Ernest N. Morial Convention Center, with online/hybrid participation options. Learn more at annual.ametsoc.org.

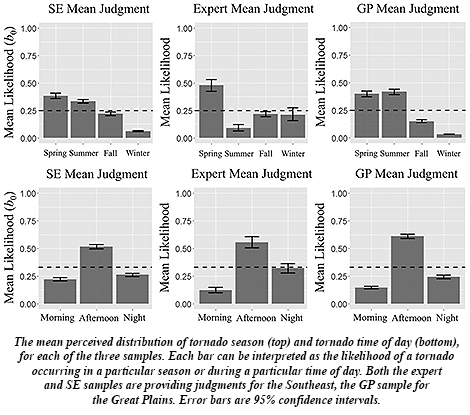

For starters, unlike in infamous “Tornado Alley” states of Texas and Oklahoma north through Nebraska and Iowa into South Dakota, the Southeast lacks a single, “traditional” tornado season, with tornadoes “spread out across different seasons,” Broomell along with his coauthors report, including wintertime. The Southeast also endures more tornadoes overnight, as happened last week in North Carolina. And they spawn from multiple types of storm systems in the Southeast, more so than in the Great Plains. This makes knowledge about residents’ regional tornado likelihood especially critical in Southeastern states.

For starters, unlike in infamous “Tornado Alley” states of Texas and Oklahoma north through Nebraska and Iowa into South Dakota, the Southeast lacks a single, “traditional” tornado season, with tornadoes “spread out across different seasons,” Broomell along with his coauthors report, including wintertime. The Southeast also endures more tornadoes overnight, as happened last week in North Carolina. And they spawn from multiple types of storm systems in the Southeast, more so than in the Great Plains. This makes knowledge about residents’ regional tornado likelihood especially critical in Southeastern states.