A Program Spotlight for the 16th Conference on Environment and Health

On Monday of the AMS 105th Annual Meeting, the 16th Conference on Environment and Health will host a full agenda of special events and sessions on climate justice and community-engaged research, with a special focus on the Gulf Coast. We spoke with symposium co-organizers Julia Kumari-Drapkin (iSeeChange) and Jane W. Baldwin (University of California, Irvine) about environmental health and justice, and what to expect from this special day of locally focused programming. View the full schedule for the Conference on Environment and Health.

Why did you decide to do a program focused on the Gulf Coast?

The Gulf Coast is America’s frontline for environmental health and justice. Tackling the interdisciplinary climate, health, and economic impacts here offers an unparalleled lens to scale critical insights and innovations to the rest of the country and the world.

What happens in the Gulf Coast has national and global implications: Its major ports, supply chains, ecosystems, and communities are integral to the U.S. economy and energy infrastructure. If the five U.S. Gulf states were considered a single country, they would rank 7th globally in GDP. Half of the nation’s petroleum refining, natural gas production, and downstream chemical processing occurs here, and local ports handle trillions of dollars in goods annually. Gulf Coast marine habitats, wetlands, and river systems also sustain fisheries, recreation, and tourism.

Despite these economic riches, Gulf Coast communities face significant disparities in income inequality and health outcomes. Mortality rates from conditions like cancer, COVID-19, heart disease, and diabetes are much higher compared to the national average, with poverty rates 35% higher and income inequality indices 20% greater as well. Communities along the Houston Shipping Channel, Beaumont, and the river parishes between New Orleans and Baton Rouge—known as “Cancer Alley”—are some of the most concentrated petrochemical zones in the country. Compounding these challenges are increasing climate risks, systemic racism, and environmental injustices, all of which shape the social determinants of health in the region.

What will the program look like?

The day will begin with a keynote address by Dr. Beverley Wright, a pioneer in environmental justice and the executive director of the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice. Her presentation on resilience will explore collaboration models for communities, scientists, and researchers to address environmental health challenges.

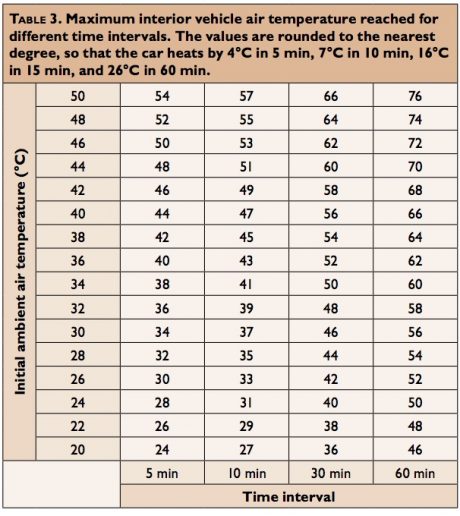

Following the keynote, a panel on extreme heat will be led by the City of New Orleans Department of Homeland Security and Emergency Management. This session will examine city-led initiatives, novel energy and housing policies, and community-driven solutions.

In the afternoon, a lunch-hour Town Hall will spotlight environmental justice leaders from the Gulf South. Topics will include industrial pollution, emergency preparedness in petrochemical zones, daily climate impacts on under-resourced communities, and lessons learned 20 years after Hurricane Katrina.

Complementary to these special events, Monday’s research sessions will focus on community-engaged research partnerships. Presentations will discuss heat, health, and flood mitigation and highlight lessons from cities like New Orleans, Houston, Austin, Pittsburgh, Seattle, and Phoenix.

Finally, during the afternoon poster session, an AMS Connections Lounge titled “Climate and Health: Interdisciplinary Connections!” will provide a time and place for individuals across the climate-health research spectrum to network and forge new opportunities for collaboration. Whether you are new to these topics or already deeply engaged, we encourage you to stop by!

Who should attend, and what will they learn?

This programming is designed for atmospheric scientists, community leaders, policymakers, and anyone invested in environmental health and justice. Attendees will gain insights into:

- Best practices in emergency preparedness, community science, tropical storm management, heat policy, and flood mitigation.

- The critical importance of collaborating with communities and the medical and health sciences sectors to address climate vulnerability and health impacts.

- Opportunities to expand research and partnerships that advance environmental justice outcomes.

The Gulf Coast serves as a microcosm for climate-induced challenges and solutions. Its rich experience in managing extreme weather and environmental justice provides valuable lessons for other regions. Attendees will leave with actionable knowledge to foster partnerships and drive innovations, setting the stage for continued collaboration at next year’s AMS meeting in Houston.

Photo at top: Effects of sediment at East Timbalier Island, Lafourche Parish, Louisiana, July 2000. Photo credit: NOAA Restoration Center, Erik Zobrist.

About the AMS 105th Annual Meeting

The American Meteorological Society’s Annual Meeting is the world’s largest annual gathering in the weather, water, and climate spheres, bringing together thousands of scientists, other professionals, and students from across the United States and the world. Taking place 12-16 January, 2025, the AMS 105th Annual Meeting will highlight the latest scientific and professional advances in areas from extreme weather to environmental health, from cloud physics to space weather and more. In addition, cross-cutting interdisciplinary sessions will explore the theme, “Towards a Thriving Planet: Charting the Course Across Scales.” The meeting takes place in New Orleans, Louisiana, at the Ernest N. Morial Convention Center, with online/hybrid participation options. Learn more at annual.ametsoc.org.