Earth hit record highs in global temps, greenhouse gases, sea level, and more last year.

By AMS Staff

Last year, global high temperatures, warm oceans, and massive wildfires broke records and sparked increasing concern about climate change. Now the annual State of the Climate report, produced by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) and peer reviewed and published by the American Meteorological Society, gives us an in-depth global picture of 2023, a year of extremes.

According to the NOAA/AMS press release, the State of the Climate report this year includes contributions from more than 590 scientists from 59 countries, and “provides the most comprehensive update on Earth’s climate indicators, notable weather events, and other data collected by environmental monitoring stations and instruments located on land, water, ice and in space.”

Below are a few highlights from 2023.

Record-high greenhouse gases (again)

Global atmospheric carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide all reached higher concentrations than ever recorded. CO2 was 419.3±0.1ppm, 2.8 ppm higher than in 2023 and 50% higher than pre-industrial levels. This is the fourth-largest recorded year-to-year rise in CO2.

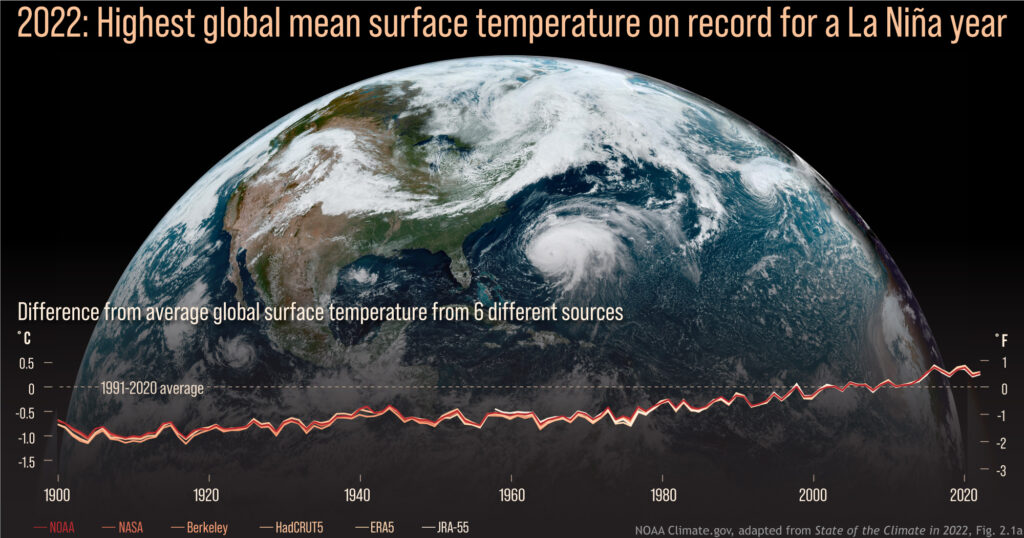

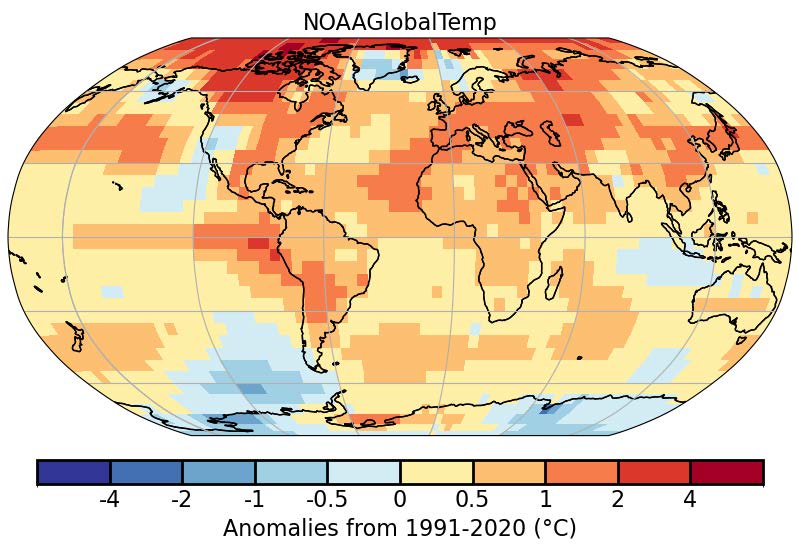

Record-high global temperatures

2023 officially beat 2016’s record as the hottest year overall since records began in the 1800s, partly due to the transition from La Niña to a strong El Niño. Globally, 2023 was 0.99°–1.08°F (0.13°–0.17°C) above the 1991–2020 average. The years 2015–2023 have been the hottest nine years on record.

North America overall experienced its warmest year since records began in 1910, including a heat wave in Mexico that killed 286 people. The Caribbean also experienced its warmest recorded year, and Europe its warmest or second-warmest depending on the analysis.

In Kyoto, Japan, the cherry trees reached peak bloom on March 25, the earliest bloom in the city’s 1,200-year record. Photo: Balazs Simon on Pexels.

Record-high ocean heat

El Niño also contributed to the hottest oceans ever recorded. Mean annual global sea-surface temperature was 0.23°F (0.13°C) higher than 2016’s previous record, and August 22, 2023 saw an all-time high daily mean global sea-surface temperature of 66.18°F (18.99°C). Marine heat waves were recorded on 116 days of 2023 (vs. the previous record of 86 days in 2016) and global ocean heat content down to 2,000 feet also reached record highs.

Record-high sea levels (again)

Global mean sea level rose 8.1±1.5 mm in 2023, to reach a record 101.4 millimeters above the average from 1993, when satellite measurements began.

Massive wildfires caused by heat and drought

37 million acres of Canada burned in 2023, twice the previous record, causing evacuations for more than 232,000 people and with smoke affecting cities as far away as western Europe. Australia experienced its driest August–October since 1900, leading to millions of acres burned in bushfires in the Northern Territory. The European Union experienced its largest wildfire since 2000 (in the Alexandroupolis Municipality of Greece). Notable wildfires also occurred in Brazil, Paraguay, and in the U.S. state of Hawaii.

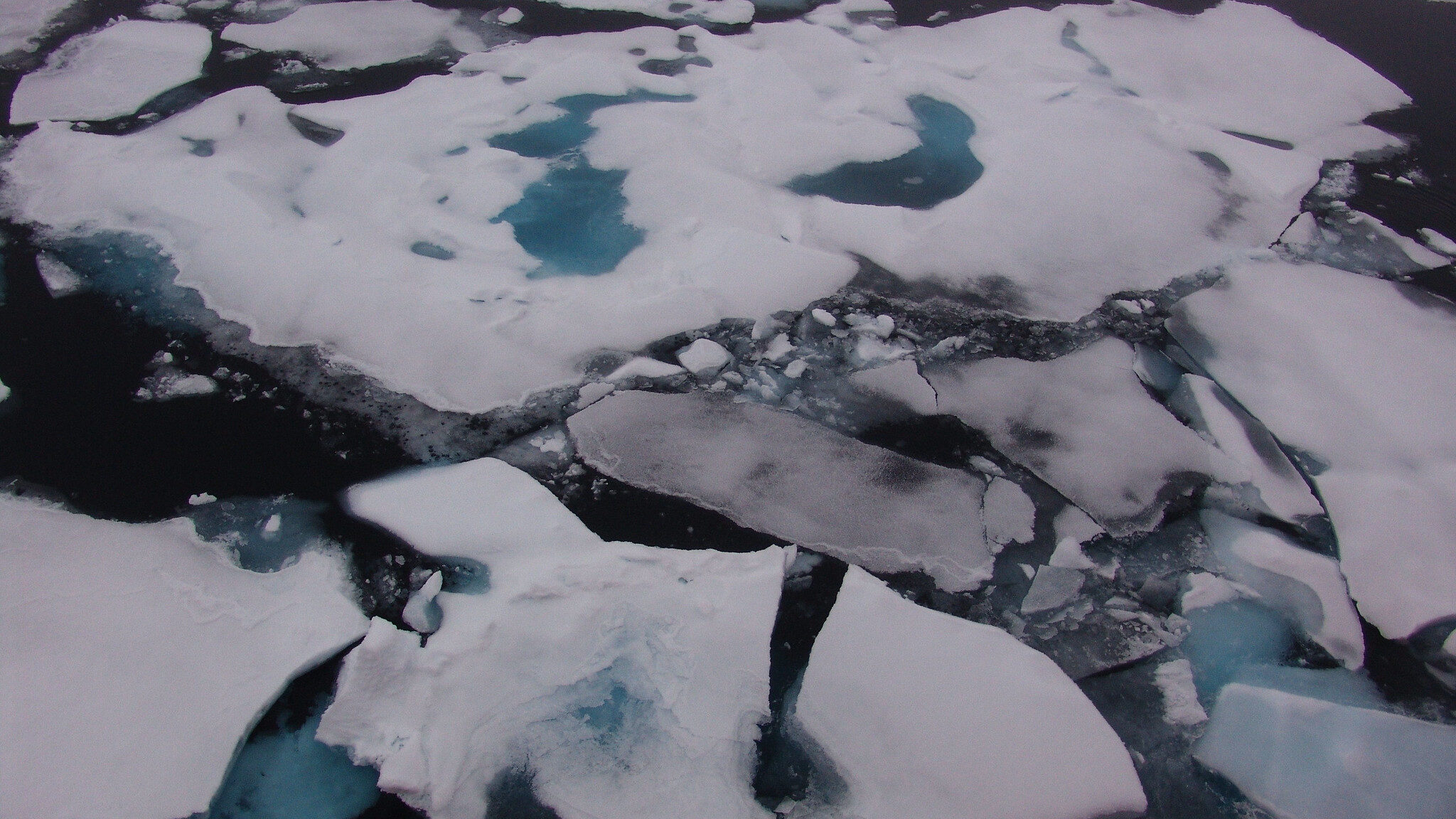

Warm poles and a greener Arctic

2023 was the fourth warmest year in the Arctic in the 124-year record, and the warmest recorded June–September. Sea ice reached its fifth-lowest extent in the 45-year record (with many monthly and daily records set), and multi-year ice declined. Despite above-average spring snowpack in the North American and Eurasian Arctic, rapid melting led to record and near-record lows in snow-water equivalent by June. The Northern Sea Route and Northwest Passage both opened, and the Northwest Passage saw a record 42 ship transits. Arctic tundra vegetation reached its third-greenest peak in the 24-year record.

Much of Antarctica also experienced well-above-average heat. In addition, eight months, and 278 days, saw record lows in sea ice extent and area in Antarctica; daily sea ice extent on 21 February was the lowest ever recorded.

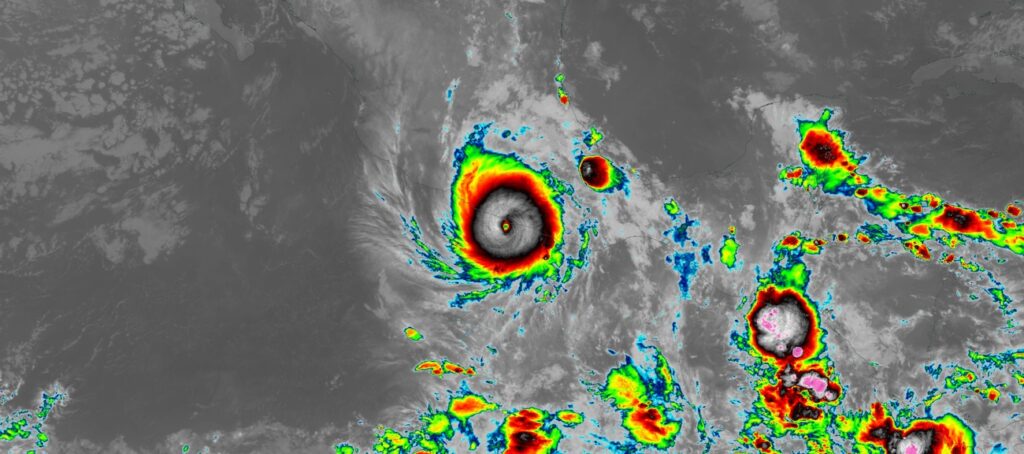

Below-average tropical cyclone activity, yet notable storms

There were 82 named tropical storms in 2023, below average. However, global accumulated cyclone energy was above average, rebounding from 2022’s record low, and there were seven Category 5 cyclones. Tropical Cyclone Freddy became the longest lived tropical cyclone on record, lasting from February 6 to March 12; it made landfall three times and caused 165 fatalities in Mozambique and 679 fatalities in Malawi due to flooding and landslides. Typhoon Doksuri/Egay was the costliest economically, causing US$18.4 billion in damages; Beijing saw its heaviest recorded rainfall and 137 residents died in flooding. Rain and floods from Storm Daniel killed at least 4,300 people in Libya. Hurricane Otis underwent the most extreme rapid intensification on record—Category 1 to Category 5 in only nine hours—and became the strongest landfalling hurricane to hit western Mexico, devastating Acapulco.

Persistent ozone hole

The stratospheric ozone hole over Antarctica appeared earlier in the year and lasted longer than normal, and reached its 16th largest extent in 44 years.

The full State of the Climate report includes regional climate breakdowns and notable events in every part of the world. Read the full 2023 report here. Read a summary of key takeaways here.

Image at top: Ice Worm Glacier in the North Cascade mountains of Washington, United States, which was under continuous annual monitoring from 1984 onward and disappeared in 2023. Large photo: The location of former Ice Worm Glacier on 13 August 2023. Inset photo: Ice Worm Glacier on 16 August 1986. Photo credits Mauri Pelto.