“The Deepwater Horizon explosion reopened debate on the role of synoptic weather features versus ocean currents in transporting the oil spill,” says Pat Fitzpatrick of Mississippi State Univ. in his abstract for a presentation in the upcoming AMS Annual Meeting.

This debate is a result of conflicting experiences with oil spills in windy storms. A storm notoriously expanded the Exxon Valdez oil slick in Prince William Sound in 1989, but on the other hand Hurricane Henri in 1979 basically had little effect on the plume of the Ixtoc spill and paradoxically cleaned up soiled Texas beaches.

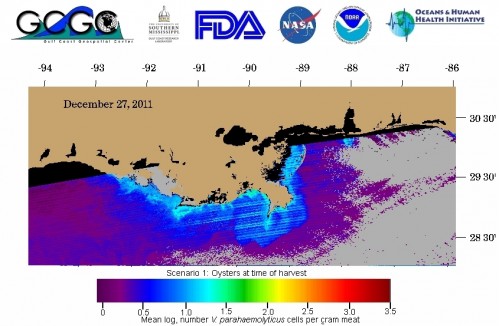

We’ll know what chances this case has of settling the debate over how winds and storms move oil slicks around after seeing the data Fitzpatrick presents (Monday, 23 January, 4:30 p.m., Room 337) from the 2010 disaster in the Gulf of Mexico. For now, Fitzpatrick writes, “Lagrangian models generally assume oil concentrations travel largely proportional (80-100%) to ocean currents’ speed and direction, plus an additional 3% contribution from surface winds, diffused with each time step. However, cyclones are known to highly perturb water pollutants….”

Add another finding to this mix, however: A paper published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences confirms previous reports that most of the oil in the Deepwater Horizon disaster never made it to the surface. Of course, it makes sense that oil plumes from an undersea explosion might stay underwater. In this case, scientists say, the plumes consisted of microscopic particles of pollution–invisible to the naked eye (with or without a scuba mask). More than a third stayed deep in the Gulf; a quarter of the is unaccounted for. From the Sarasota Herald Tribune:

“The visible surface slick that people were riveted by during the months of the spill was really only 15 percent of the total mass,” said Thomas Ryerson, a research chemist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration who led the study.

It will be interesting to see if such varying conditions of oil releases from different disasters over the years will add up to a coherent understanding of the interaction of ocean and atmosphere that can be used to improve predictions of the movement and effects of the next big spill.