New data from the past ten years reveal increased prominence of freshwater floods and indirect fatalities in hurricane deaths

Guest post by Dr. Michael Brennan, Director, National Hurricane Center; Daniel Brown, Warning Coordination Meteorologist, National Hurricane Center; and Leah Pope, Hydrologist, Northwest River Forecast Center

The National Hurricane Center’s mission to “save lives and mitigate property loss” is not just achieved by issuing effective watches, warnings, and forecasts of tropical cyclones. We also spend a large portion of the “offseason” educating the public, emergency managers, and our media partners about the risks that tropical cyclones (TCs), including hurricanes, pose to life and property in the United States. Those include natural hazards such as storm surge, wind, and rip currents, and also includes dangerous conditions in the aftermath of a landfalling tropical cyclone, which may lead to “indirect” fatalities. These are deaths which are not directly due to the forces of the storm, but which would not otherwise have occurred. NHC routinely compiles and assesses TC-related information through vehicles such as our Tropical Cyclone Reports (TCRs). Data from the most recent decade reveal that fatality trends may be changing.

Note: The fatality data presented here do not include any fatalities from Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico, since there was no specific, definitive cause provided for those deaths.

Direct Fatalities

Previous studies by Rappaport (2014) and Rappaport and Blanchard (2016) summarized direct and indirect fatality data from Atlantic basin tropical cyclones in the United States for the 50-year period 1963–2012. During that period, nearly 9 out of 10 tropical cyclone-related direct deaths in the United States were due to water. Storm surge was responsible for nearly half (49%) of the direct deaths, and over one-quarter (27%) were due to rainfall-induced freshwater flooding.

In response, the National Weather Service (NWS) and NHC worked to improve outreach, education, and communication of storm surge and rainfall hazards. We introduced new real-time storm surge maps in 2014, and in 2017 introduced a storm surge watch/warning that highlights the risk of life-threatening storm surge inundation.

New Data Suggest Changing Trends

Since 2012, the United States has experienced 21 hurricane landfalls, including 8 major hurricanes, and more than 20 tropical storm landfalls. Eighteen of these hurricane landfalls, including all of the major hurricanes, occurred during 2017–22 after a relatively quiet period. Given the significant number of tropical cyclone landfalls in recent years, and increased deployment of warnings around the storm surge hazard, NHC examined and compared fatality data from the most recent 10-year period (2013–22) to the earlier studies.

| Hazard | % of direct fatalities from this cause (1963–2012) | % of direct fatalities from this cause (2013–2022) |

| Storm Surge | 49% | 11% |

| Freshwater Flooding | 27% | 57% |

| Wind | 8% | 12% |

| Surf/Rip Currents | 6% | 15% |

| Offshore Marine Incidents | 6% | 3% |

| Tornadoes | 3% | 2% |

| Other | 1% | 1% |

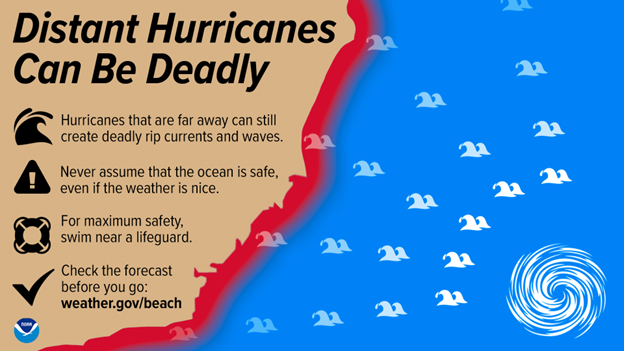

During the most recent 10-year period in the United States, about 57% of direct tropical cyclone deaths were due to drowning from freshwater (rainfall) flooding. Surf and rip current fatalities have become an increasing threat, making up about 15% of direct fatalities in the past decade. These fatalities often occur one or two at a time from distant storms hundreds of miles offshore. Florida, North Carolina, and New Jersey experienced the highest number of TC-related surf and rip current fatalities. Storm surge and wind-related deaths account for 11% and 12% of the direct fatalities, respectively.

Every hurricane is different, however. Hurricane Harvey in 2017 had the largest number of direct deaths—68, 65 of which were due to freshwater flooding in Texas—in the past decade. Hurricane Ian (2022) was the second deadliest with 66 direct fatalities, 41 of which were due to storm surge in Florida. More than 65% of those who died from direct causes were men, with about 60% of the victims over the age of 60.

Indirect Causes

The recent study revealed that over the past 10 years there has been nearly an equal number of indirect deaths as direct fatalities. Indirect fatalities are due to a wide range of causes, including traffic accidents (16%), preparation/cleanup accidents (15%), carbon monoxide poisoning (12%), lack of medical care (11%), power problem/electrocution (11%), post-storm heat deaths (9%), unknown causes (9%), cardiac-related deaths (7%), and evacuation-related deaths (5%).

The largest number of indirect deaths in the past decade occurred in association with Hurricanes Ian (90), Irma (82), Michael (43), Harvey (35), and Laura (34). Most (75%) of the indirect deaths are associated with major hurricane landfalls, which leave communities very vulnerable and often with long-duration, widespread power outages. More than half (57%) of the victims were over the age of 60. Younger victims tended to die in vehicle accidents; for older victims, medical-related issues, heat, evacuation, and other accidents were more likely causes of death.

Improving Warnings and Public Understanding

The results of these most recent studies have led the NWS and NHC to increase messaging on the hazards and causes of both direct and indirect fatalities. We continue to highlight rainfall flooding and storm surge risk through the Weather Prediction Center’s Excessive Rainfall Outlook, Flood Warnings from local NWS offices, and increased emphasis on the Storm Surge Warning. These warnings are the loudest “bells” that the NWS can ring during life-threatening flooding. We encourage our media and emergency management partners to work with us to encourage timely public response and personal preparedness ahead of these threats.

Additionally, with the increased percentage of rip current fatalities associated with high surf and swells from distant hurricanes, the NWS has created new infographics to explain this deadly beach hazard, and is working on graphics to better highlight the threat in real time.

During the highly impactful 2020 hurricane season in the United States, there were more fatalities associated with carbon monoxide poisoning from the improper use of generators than there were from storm surge. After that season, NHC and the NWS developed infographics and worked with media and emergency management partners to highlight that threat. While it is difficult to determine the effectiveness of that messaging, it is encouraging to know that there were no carbon monoxide related-fatalities in the aftermath of Hurricane Ian in 2022 in Florida, despite its devastating impacts and widespread power outages in that state.

NHC relies on relationships with media, emergency management partners, and the entire weather enterprise to help reach the public before, during, and after tropical cyclone threats. These efforts undoubtedly increase awareness, encourage preparation, and save lives. We hope to continue to improve our messaging and understanding of the threats and causes of injuries and fatalities to better meet our collective mission.

Visit the National Hurricane Center online.

Header photo: Hurricane Gonzalo in the Atlantic. Photo taken by GOES East satellite at 1445Z on October 14, 2014. Photo credit: NOAA.

This post was invited based on a presentation given by Dr. Brennan at the 50th Conference on Broadcast Meteorology, which took place in Phoenix, Arizona, June 21–23, 2023. The conference was organized by the American Meteorological Society Board on Broadcast Meteorology and chaired by Danielle Breezy and Vanessa Alonso.