Highlighting Key Sessions at AMS 2025

A symposium at the 105th Annual Meeting of the American Meteorological Society will honor Gerald (Jerry) Meehl, a nationally and internationally recognized leader in climate dynamics, climate change, climate modeling and Earth system predictability, and present cutting-edge science in his areas of expertise. Meehl is currently a Senior Scientist at the NSF National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR), section head of the Climate Change Research Section, and the Principal Investigator/Chief Scientist for the DOE-NCAR Cooperative Agreement To Analyze variabiLity, change and predictabilitY in the earth SysTem (CATALYST) project.

We spoke to Gerald A. Meehl Symposium Co-Chair Aixue Hu, Project Scientist in the Climate and Global Dynamics Lab at NSF NCAR, about the field, Dr. Meehl, and what to expect during the symposium, which takes place Tuesday, 14 January, 2025.

“Jerry is a living, breathing encyclopedia of the history behind the history of climate science.”

–Maria Molina, NSF NCAR/University of Maryland

What can attendees expect from the Symposium?

This symposium will honor Dr. Meehl’s service to the climate research community (including his contributions to the CMIP and IPCC assessment reports); and will highlight the current state of research on climate variability, predictability, and change.

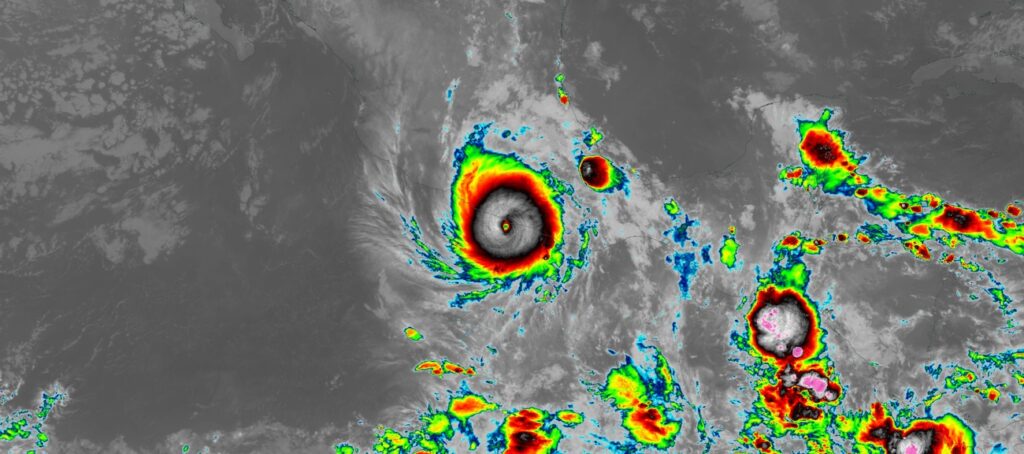

Presentations will discuss topics including extreme events, climate dynamics, marine heat waves, subseasonal to decadal climate prediction and predictability, AI and machine learning in climate research and prediction, and interactions between internal variability and external forcings – along with current modelling efforts and the future directions of model improvements.

Why is this such an important field right now?

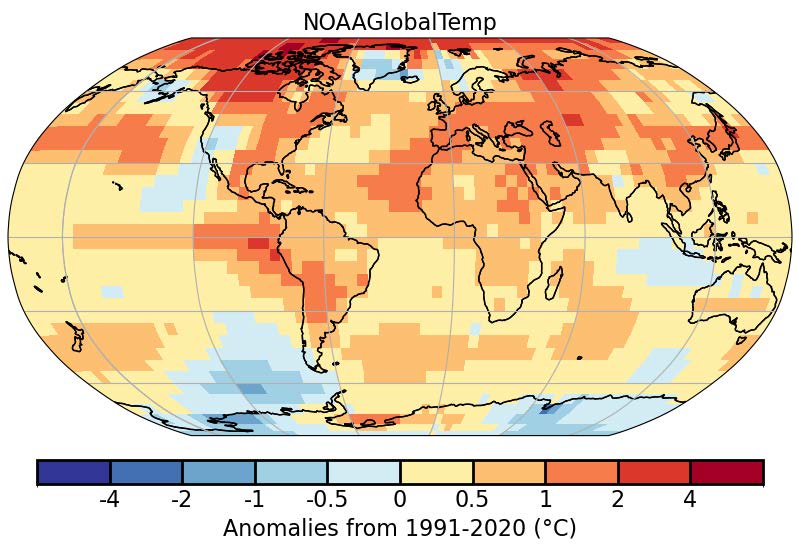

The global mean temperature continues to rise, and most of the hottest years on record have appeared in the most recent decade. This change in the mean background climate can result in significant impacts on accurate weather forecasts, and on subseasonal to seasonal to decadal predictions. For example, with a much warmer mean climate, the chance for extreme weather events (heat waves, hurricanes, extreme precipitation) increases. Society benefits from improving our understanding of how this change in mean climate will affect our capability to accurately predict/forecast the weather on shorter timescales, and ENSO and decadal climate modes on longer timescales.

How would you summarize Jerry Meehl’s impact on the field so far?

Over the years, Jerry has spearheaded several new research directions focused on climate models. For example, his work has greatly advanced our understanding of the global warming slowdown in the early 2000s (the “hiatus”) and explored its predictability. His pioneering 2011 Nature Climate Change paper on this topic was named one of the five most influential papers in the first five years of Nature Climate Change (2016). His work has also been crucial to the study of extreme temperature events, monsoons, and decadal climate variability and predictability.

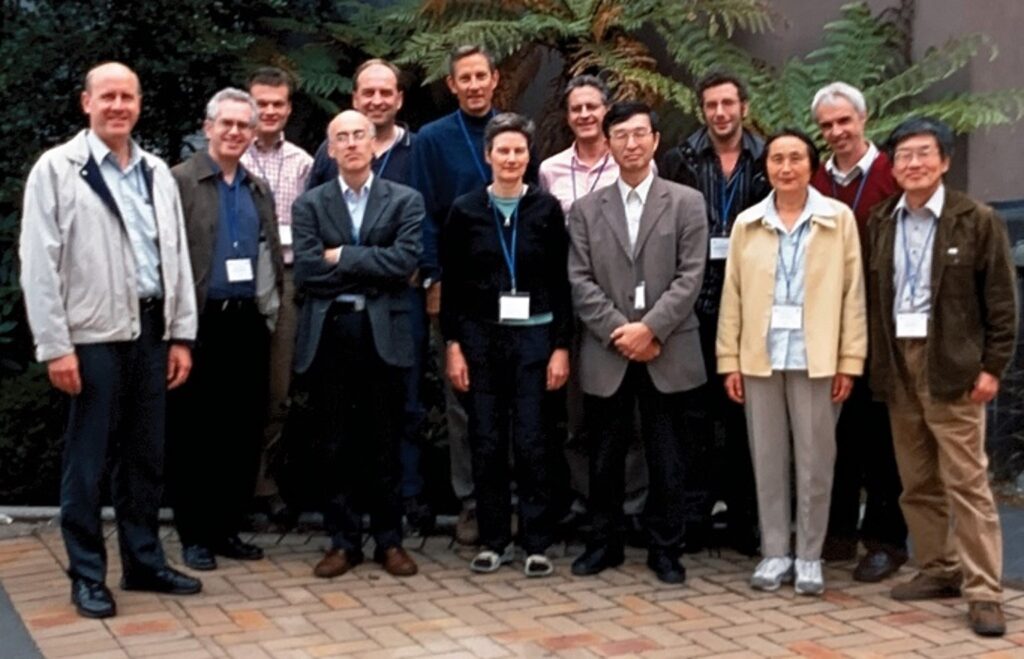

Jerry chaired the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP) Panel under the World Climate Research Program (WCRP) from 1997 to 2007. He led the formulation of the CMIP1 through CMIP3 projects and continued to serve on the panel as it formulated CMIP5 and 6. CMIP1-3 provided the physical science foundation for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) AR3 and AR4 reports.

Dr. Meehl also chaired the WCRP Working Group on Coupled Models (2004-2013) and the National Academy of Sciences/National Research Council Climate Research Committee (2008-2011), among other prominent national and international committees. He was a contributing, coordinating, or lead author for the IPCC AR1-AR5 reports, and a member of the IPCC science team that was awarded the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize.

Photo: Author team for Chapter 10, “Global Climate Projections,” IPCC Fourth Assessment Report (AR4), Christchurch, NZ, 2005; coordinating lead authors Jerry Meehl and Thomas Stocker are center back. Photo courtesy of Jerry Meehl.

The AMS has recognized Jerry’s scientific contributions to, and leadership in, climate research, awarding him the Jule G. Charney Award in 2009 “for outstanding collaborative contributions to modeling climate and its response to anthropogenic and natural forcings” and the Sverdrup Gold Medal in 2023 “for seminal work integrating observations, models, and theory to understand variability and change in the ocean and atmosphere.” He is also a fellow of AMS since 2006, and of AGU since 2014. He has also been recognized by organizations including Reuters and Web of Science as an influential and very highly cited researcher.

Left photo: Jerry Meehl and Warren Washington awarded the AMS Charney Award, in Phoenix, AZ (2009). Right photo: Group photo of participants in the Warren Washington Symposium at AMS, January 2010, convened by Dave Bader and Jerry Meehl; the only time that “legends of climate modeling” Suki Manabe, Larry Gates, Warren Washington, and Jim Hansen attended the same meeting at the same time. From left: Kirk Bryan, Suki Manabe, Jerry, Greg Jenkins, Larry Gates, Jane Lubchenco, Steve Schneider, Dave Bader, Warren Washington, John Kutzbach, V. Ramanathan, Jim Hansen, Bert Semtner. Photo credits: American Meteorological Society.

Even as a world famous climate scientist, Jerry is very approachable. He makes himself available to young scientists and gives them unselfish guidance and support. When Jerry was leading the CMIP effort and was lead author for the IPCC assessment reports, his communication skills helped move the CMIP effort forward, and he navigated through differences among lead authors smoothly. Jerry is not only a great scientist, but also a great mentor, communicator, and writer. He has worked with numerous graduate students, post-docs, and junior researchers and left significant impacts on their careers. That includes being my own mentor and role model for over 20 years!

It might be a surprise to many people, especially the early career scientists, that Jerry is also a writer. He has authored and co-authored six books that grew out of his personal interests in World War II, especially in the Pacific theater. His ability to communicate and relate to others shines through no matter what he does!

The Gerald A. Meehl Symposium will be held Tuesday, 14 January, 2025 at the AMS 105th Annual Meeting, in New Orleans, LA, and online. Learn more about the Symposium and view the program.