In 2011, Texas experienced its hottest summer on record along with a drought that has yet to let up. According to the state drought monitor released last week, sixty-five percent of the state was in severe drought, up from fifty-nine percent just a week earlier. As we head to Austin for the Annual Meeting in a few weeks the topic will be up front and center at a number of events planned.

“Anatomy of an Extreme Event: The 2011 Texas Heat Wave and Drought” will examine processes, underlying causes, and predictability of the drought. Martin Hoerling of NOAA ESRL-PSD and other speakers will use observations and climate models to assess factors contributing to the extreme magnitude of the event and the probability of its occurrence in 2011 (Wednesday, 9 January, Ballroom B, 4:00 PM).

On Tuesday, Eric Taylor of Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service will speak on the “Drought Impacts from 2011-2012 on Texas Forests.” Taylor notes that the impacts of the 2011 drought on the health, biodiversity, and ecosystem functions will be felt for some time, but perhaps not in the way that most might think. During this session, he will explore the ways that the silvicultural norm practiced by private landowners affect forest health and the concomitant loss from insects, disease, wildfire, and drought (Tuesday, 8 January, Ballroom E, 1:45 PM).

The 27th Conference on Hydrology will cover a number of other drought issues both in Texas and beyond. For more information on drought and related topics, take a look at the searchable Annual Meeting program online.

droughts

The Storm That Started a Drought?

by Robert V. Sobczak, National Park Service, Big Cypress National Preserve.

Reposted from his blog, The South Florida Watershed Journal.

Do all storms end with drought?

I know you’re thinking. I mean the opposite instead:

That “all droughts end with a flood,” right?

A meteorologist in the snow-bound climes of the Red River Basin introduced me to the latter saying. To what degree it holds any statistical truth I cannot say. My initial gut reaction was that an observational bias was in play, plus some seasonal slight of hand. But no matter how much I tried to deny it, the saying kept sneaking up on me wherever I roamed.

Take Tropical Depression Nicole for example. It threatened to make our already high-water rendition of the Big Cypress Swamp all the more wetter but by the flap of the wings of the butterfly bypassed to the east and then onward north to the Atlantic Coast where it drenched those watersheds instead.

Now here’s the catch:

Those watersheds were at the end of their seasonal drought, better known as the summer recession, transforming currents from trickles into torrents overnight.

So yes, chalk one on the board for that old reliable saying!

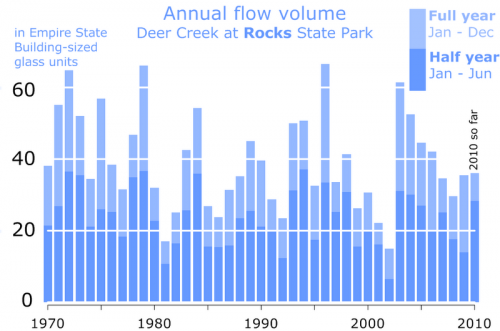

Case in point is Maryland’s Deer Creek, as measured at Rocks State Park (or just “Rocks” as us Harford Countians call it). Thanks to Nicole it now has a chance to top 40 Empire State Buildings (ESBs) worth of water flow for the year. That would make it an above average year, but not a “chart topper,” a term I reserve for the biggest of big flow years which pass 60 or more ESBs worth of water. That’s happened just four times in the modern era (aka my lifetime), the most recent of which (2003) which was, as predicted by that old reliable saying, preceded by the drought of record in 2002 when less than 20 ESBs worth of water flowed through Maryland’s famed Rocks State Park for the year.

Ha, there it is again! So, cherry picking not withstanding, I guess that means that, yes, all drought do seem to end with floods.

Does the same saying apply to the Florida swamps?

Seasonally it happens each year with our winter dry season. By spring the swamps are nearly 100 percent water free and crunchy, just a single lightning strike away from an uncontrollable blaze. But along with the lighting are the thunder that beckon the wet season’s arrival … and the floods that will soon be to follow.

Which brings me back to Nicole:

Instead of flushing flood waters even higher into the swamp it paradoxically reversed the tables by ushering in a week’s worth of dry air in its wake instead.

Meteorologists are calling it an early start to the dry season.

Or in other words…

Call it the storm that started the drought!