One of the highlights of New Orleans is its distinctive, world-renowned cuisine. And indulging in that famous cuisine more often than not means enjoying the bounty of the Gulf of Mexico. AMS members will descend on New Orleans right at the high season for oysters, according to food critic Brett Anderson writing in the local paper, the Times-Picayune, right before Christmas:

Meteorologically speaking, it is an inconvenience that Louisiana oysters are never more delicious than they are right about now, just as we’re growing accustomed to the daily threat of something resembling winter. Wouldn’t it be nice if oysters were at their crispest in August instead, when they could provide cool relief from the blood-hot sun? Yes, that would be nice, but our reality is pretty sweet as well: oysters at their peak, tasting like clean ocean water, firm-fleshed and sitting pert on their shell. They’re perfectly sized, large enough to announce their presence, small enough to swallow whole. Get another dozen. It’s gift-giving season.

According to the reports from the restaurants, the local crop is back to the quality seen before the big BP Horizon oil spill of 2010. Prices and supplies have normalized.

So while you’re hunting for some Gulf oysters on the half-shell later this month at the AMS Annual Meeting, keep in mind that this delicacy is not only featured on your plates but, also, featured on scientific program. In particular, two presentations might ease concerns you have about subjecting your stomach to the raw variety (of food, not science, of course!). Gina Ylitalo (NOAA) and colleagues will present on “Oil Spills and Seafood Safety” (8:45 p.m., Tuesday, Room 333). They write

Thousands of seafood samples collected during reopening and surveillance in the Gulf, as well as those obtained dockside and in the marketplace have been analyzed using [advanced] analytical methods. While chemical compounds associated with the oil spill have been detected in seafood samples using these various analytical methods, none were present in edible tissues at levels that approached levels of concern for human consumers of seafood products from the Gulf.

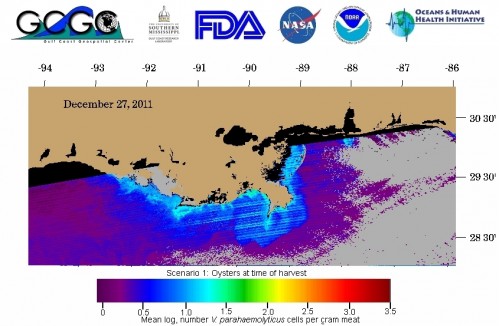

Later in the same session on Tuesday, Jay Grimes (Univ. of Southern Mississippi) will talk about monitoring disease potential from raw seafood with satellite monitoring of ocean temperatures and salinity, in “Can You Really See Bacteria from Space?”. Below is the latest bacteria estimate from their oceanographic monitoring website: