Next week on Friday (11 December), 7 p.m. Central Time, the University of Texas-Austin will present a live Webcast of “Global Warming—Lone Star Impacts,” a lecture by Gerald North ofTexas A&M.

It should be an interesting occasion, not just because North is an experienced scientist and climate change is a hot topic, but also because of the timing. The lecture was supposed to be delivered this past Friday, yet an unseasonable snowstorm got in the way. Ah, the inconvenient truths of climate: day-to-day weather can be uncooperative.

As SciGuy blogger Eric Berger for the Houston Chronicle observes: “What does snow falling in Houston have to do with global warming? Nothing. Nada. Zip.” For emphasis, Berger also posted a great photo from a record Houston snowfall in 1895, not to be missed by history buffs.

Friday’s storm across the Gulf Coast delivered the earliest snow on record for Houston–but just five years ago the region had a Christmas snowfall with depths of up to 13 inches.

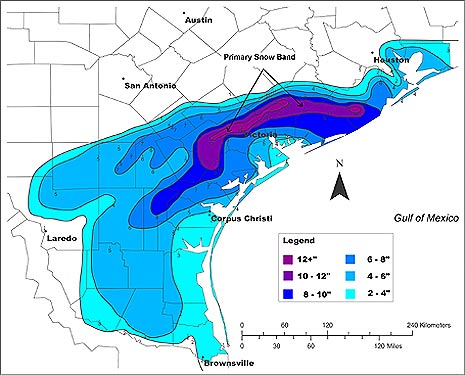

Fortunately this week’s snow was lighter, but if you’re interested in a detailed perspective about how Gulf coast snow mechanisms can be surprisingly prolific and yet quite “ordinary”, check out the poster by Ronald Morales presented at the 2007 AMS Conference on Mesoscale Processes. It’s full of vivid satellite and radar imagery from the 2004 storm, as well as this overview of the snowfall.

3, 2, 1…You're On the Air

Yes, this blog is on the air…but it’s about a lot of other subjects, too.

There was a time when meteorology meant all things atmospheric. But that’s not enough anymore. The air we breathe reflects the crops we grow, the cities we build, and the cars we drive. Air picks up water and salt from the oceans, and mixes dust from our barren fields and sand from hostile deserts. It absorbs and relays radiation from above and below, responding to solar eruptions from afar. It mixes all of that and more to make weather.

In short, the air is a convergence of physics, chemistry, biology, sociology, economics—practically every branch of knowledge. Long ago meteorology morphed into “atmospheric, oceanographic, hydrologic, and related sciences” and then it became something even more complicated—bigger and more interconnected.

When you look at the 90-year-old AMS seal, though, what you see is not an enumeration of sciences—physical and social—convening under one big umbrella. Rather, what you see is a circle of applications—public health, engineering, agriculture, commerce, aerial navigation, and so on. Science and service converge on weather.

When you look at the 90-year-old AMS seal, though, what you see is not an enumeration of sciences—physical and social—convening under one big umbrella. Rather, what you see is a circle of applications—public health, engineering, agriculture, commerce, aerial navigation, and so on. Science and service converge on weather.

Isn’t it striking, then, that we keep circling back to that spirit of 1919, the founding of AMS. The theme of the upcoming AMS Annual Meeting is “Weather, Climate, and Society: New Demands on Science and Services.” The Presidential Forum brings together public health and air transportation experts; the meeting also delves into renewable energy and insurance. One of the plenary talks is aptly titled, “A Science of Service.”

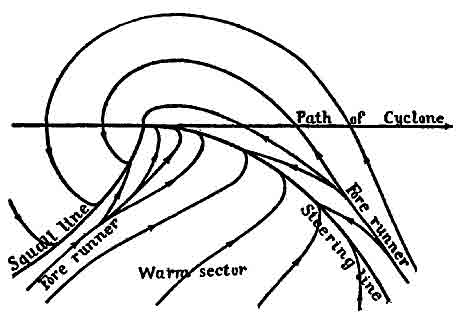

Just weeks after AMS was born, Monthly Weather Review introduced American readers to Jacob Bjerknes’ landmark paper, “On the Structure of Moving Cyclones.” It was part of the scientific revolution in forecasting based on the convergence of airstreams. Ever since, those convergences—“fronts”—have been synonymous with weather, and oceans too.

Fronts and the AMS thus have shared nine decades of mutual history. The Front Page will be informal and spontaneous, like the weather, airing all sorts of perspectives. It is the latest in a long line of everyday convergences of science and service.