John Snow, a veteran professor of meteorology at the University of Oklahoma (OU), retired dean of the OU College of Atmospheric and Geographic Sciences, and a founding member of the OU National Weather Center, is the 2013 recipient of The Kenneth E. Spengler Award. He is being recognized this year for his exceptional foresight and leadership in melding a diverse group of people in designing a new Commission of the AMS—the AMS Commission on the Weather and Climate Enterprise—to meet ever expanding weather and climate enterprise needs.

The Front Page caught up with Dr. Snow to learn about his role in the formation of the Commission, which now encompasses a number of committees and boards to focus on specific disciplines and interests. He also shared his special interest and active involvement with the Board on Enterprise Economic Development, which he says not only fascinates him because of the private sector’s solid foundation but also because of its dynamic growth.

Click on the image below to view the interview.

A Promising Trend in Lightning Safety

Since 2006, lightning has been the third most common cause of storm-related deaths in the United States, behind only floods and tornadoes. But lightning deaths are trending downward, suggesting that educational efforts on the dangers of lightning, as well as improved warning capabilities, are making a difference. Over the past 30 years, the U.S. has averaged 54 lightning deaths per year. But over the last decade, that number falls to 32 deaths per year, with a record-low of 26 in 2011 and only 28 in 2012. Of course, some of that decline is connected to social trends: early in the twentieth century, when many more people worked outside, lightning deaths in the U.S. numbered in the hundreds per year.

At the Annual Meeting in Austin, the Sixth Conference on the Meteorological Applications of Lightning Data will look at some social factors connected to lightning fatalities, including posters on Monday in Exhibit Hall 3 by Ronald Holle of Holle Meteorology and Photography (summarizing the dangers of lightning to people sheltering near trees) and Andrew Rosenthal of Earth Networks (on the effects of lightning at sporting events). And in the 16th Conference on Aviation, Range, and Aerospace Meteorology, Matthias Steiner of NCAR will explore some of the key issues related to lightning safety at airports (Wednesday, 4:30 p.m., Room 17A).

Along with changes in behavior, education and information are cited as important factors in reducing lightning fatalities, and some of the latest developments in this area will be explored in Austin. NOAA’s new lightning fatality database collects data from media sources, local NWS offices, and local officials to compile information on U.S. lightning deaths–including various demographics and the activity of the victim at the time of the strike–that can help us understand lightning fatality patterns and educate the public on what situations are most dangerous. Private meteorologist William Roeder will present a poster on the new database and its applications to lightning safety education (Exhibit Hall 3).

The conference will explore numerous ways that lightning data can be used to understand related severe weather phenomena. For example, the Geostationary Lightning Mapper (GLM) on the GOES-R spacecraft (scheduled for launch in 2015) will be able to continuously map total lightning activity throughout the day and night, which should prove valuable in forecasting tornadoes, storm intensification, and other severe weather. NOAA’s Steven Goodman will discuss the GLM’s capabilities on Wednesday (8:30 a.m., Ballroom G). In the same session (9:30 a.m., Ballroom G), Daniel Cecil of the University of Alabama will present an algorithm for using proxy GLM data to identify lightning jumps, which are sudden increases in flash rate for a convective cell and therefore can also provide advance warning of severe weather. Another example is the use of the pseudo-Geostationary Lightning Mapper (pGLM) product, which was created for the Hazardous Weather Testbed (HWT) Spring Experiment/Experimental Warning Program. Kristin Calhoun of CIMMS and NOAA will explain how the pGLM used total lightning data to detect VHF radiation from lightning discharges, and subsequently to forecast storm modes (Wednesday, 8:45 a.m., Ballroom G).

This is just a small sampling of lightning-related research to be presented in Austin–a promising sign that continued reductions in lightning tragedies are still possible in the future.

Dealing with Drought in the Heart of Texas

In 2011, Texas experienced its hottest summer on record along with a drought that has yet to let up. According to the state drought monitor released last week, sixty-five percent of the state was in severe drought, up from fifty-nine percent just a week earlier. As we head to Austin for the Annual Meeting in a few weeks the topic will be up front and center at a number of events planned.

“Anatomy of an Extreme Event: The 2011 Texas Heat Wave and Drought” will examine processes, underlying causes, and predictability of the drought. Martin Hoerling of NOAA ESRL-PSD and other speakers will use observations and climate models to assess factors contributing to the extreme magnitude of the event and the probability of its occurrence in 2011 (Wednesday, 9 January, Ballroom B, 4:00 PM).

On Tuesday, Eric Taylor of Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service will speak on the “Drought Impacts from 2011-2012 on Texas Forests.” Taylor notes that the impacts of the 2011 drought on the health, biodiversity, and ecosystem functions will be felt for some time, but perhaps not in the way that most might think. During this session, he will explore the ways that the silvicultural norm practiced by private landowners affect forest health and the concomitant loss from insects, disease, wildfire, and drought (Tuesday, 8 January, Ballroom E, 1:45 PM).

The 27th Conference on Hydrology will cover a number of other drought issues both in Texas and beyond. For more information on drought and related topics, take a look at the searchable Annual Meeting program online.

Sandy at the AMS Meeting: A Study in Adaptation, An Opportunity to Participate

by Tanja Fransen, NOAA

Ninety-three. That is how many annual meetings the American Meteorological Society has hosted. Planning for an annual conference can take years, from selecting the location, securing the event center and hotels, to selecting the organizing committee. The organizing committee then decides upon a theme at least 15-18 months in advance. Individual conference organizers have their “calls for papers” ready nearly 14 months in advance. Presenters have to have their abstracts submitted nearly 5 months before the annual meeting.

So…what happens when you have an event that is the magnitude of Hurricane/Post-Tropical Storm Sandy after all the deadlines have passed? You adapt and overcome.

That is what happened this year. Even the Major Weather Impacts Conference, which has a later abstract deadline than most conferences, was finalized a week before Sandy become one of the most significant events in decades. Many individuals quickly realized the importance of including Sandy at the 2013 Annual Meeting, and a committee was organized. Emails started flying back and forth, discussions were occurring on message boards and social media, and ideas were flowing, to the tune of hundreds of emails, phone calls, and social media messages.

Trying not to conflict with other conferences where committees had spent over a year planning them, AMS recommended a Town Hall Session to introduce Sandy formally into the 2013 AMS meeting. And so it will be, 7:30 to 9:30 p.m. on Monday, January 7, in Ballroom E at the Austin Convention Center. Committee organizers received feedback from many sources, and in the end, decided that invited speakers would discuss the major impacts of Sandy, the scientific issues, the warnings process, and more. The list of speakers (below) is diverse, representing, for example, NOAA, NCAR, the Capital Weather Gang, the Wall Street Journal.

Over the next few months, as further discussion, research and assessments are conducted on the meteorology, climatology, communication, preparedness, response and recovery of the event, other opportunities will keep Sandy in the spotlight. That includes conferences from within the AMS, such as the 19th Conference on Atmospheric and Oceanic Fluid Dynamics from June 17-21, 2013, in Newport, Rhode Island, and the 41st Broadcast Meteorology Conference /2nd Conference on Weather Warnings and Communication being held from June 16-28, 2013, in Nashville, Tennessee, as well as the 2014 Annual AMS Meeting in Atlanta, Georgia, in February 2014. The theme for the 2014 Annual Meeting nicely encompasses Sandy in “Extreme Weather – Climate and the Built Environment: New perspectives, opportunities and tools.” Other groups, organizations and agencies will also keep those discussions in the forefront.

We know there will be many questions that people will have for the presenters in the Town Hall Meeting in Austin. With a short time frame to discuss them, attendees are asked to use Twitter to send the questions they have; the hashtag is #AMSSandy. (Also, in general follow #AMS2013 for tweeting related to the Annual Meeting.) Organizers will group the questions into categories, and ask the top 3-5 questions, depending on time, to the presenters.

Here’s the scheduled agenda at this time:

7:30 PM. Introduction to Sandy and the Major Impacts — Louis W. Uccellini, NOAA/NWS/NCEP, Camp Springs, MD

7:45 PM. Hurricane Sandy: Hurricane Wind and Storms Surge Impacts — Richard D. Knabb, The Weather Channel Companies, Atlanta, GA

8:00 PM. Post-Tropical Cyclone Sandy: Rain, Snow and Inland Wind Impacts — David Novak, NOAA/NWS/Hydrometeorological Prediction Center, College Park, MD

8:15 PM. A Research-Community Perspective of the Life Cycle of Hurricane Sandy — Melvyn A. Shapiro, NCAR, Boulder, CO

8:30 PM. Communicating the Threat to the Public through Broadcast Media — Bryan Norcross, The Weather Channel, Atlanta , GA

8:45 PM. Following the Storm through Social Media — Jason Samenow, Washington Post, Washington, DC; and A. Freedman

9:00 PM. Storm Response in New York and New Jersey — Eric Holthaus, The Wall Street Journal, New York, NY

9:15 PM: Q&A: Moderators will present 3-5 questions submitted through Twitter to the panelists.

TRMM Keeps on Truckin'

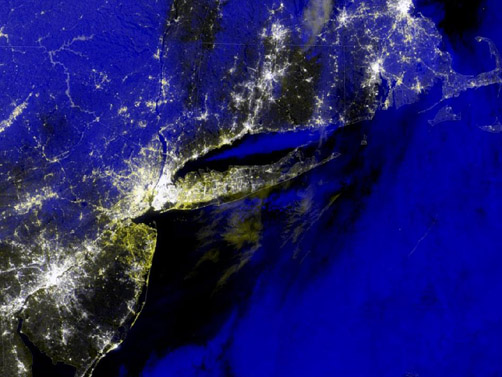

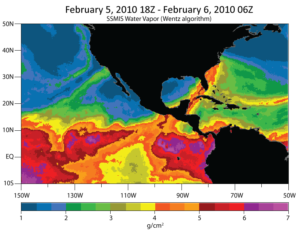

It’s been 15 years since the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) satellite was launched. Over that time, TRMM has significantly advanced our understanding of precipitation through measurements of the global distribution of rainfall at Earth’s surface, the global distribution of vertical profiles of precipitation, and other rainfall properties. As a result, TRMM provides clues to the workings of the water cycle and the relationship between oceans, the atmosphere, and land. But the benefits of TRMM extend beyond the research community. The image below exhibits the kind of operational data TRMM can supply: it’s a rainfall analysis of SuperStorm Sandy that reveals the heaviest rainfall totals during the storm (more than 10.2 inches) were over the open waters of the Atlantic Ocean.

Despite its advanced age, TRMM continues to provide unique data; its enduring value is evidenced by the fact that more than 50 presentations at the AMS Annual Meeting in Austin are related in some way to TRMM and its data. A few examples: Yingchun Chen of the University of Melbourne will examine TRMM’s estimates of daily rainfall in tropical cyclones using the Comprehensive Pacific Rainfall Database (PACRAIN) of 24-hour rain gauge observations (Wednesday, 9:30 a.m., Room 10b). A poster presentation by Dana Ostrenga of ADNET Systems and NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center will review the recently released Version 7 TRMM Multi-satellite Precipitation Analysis (TMPA) products and data services (Monday, Exhibit Hall 3). Zhong Liu of George Mason University will present a poster on the TRMM Composite Climatology, a merger of selected TRMM rainfall products over both land and ocean that provides a “TRMM-best” climatological estimate (Monday, Exhibit Hall 3). In her poster, Hannah Huelsing of the National Weather Center will show how TRMM 3-hourly data were used to look at the spatial and temporal distribution of the Asian premonsoon and monsoon seasons in Pakistan during 2010’s severe flood year (Tuesday, Exhibit Hall 3).

As TRMM matures, it’s also broadening its horizons and crossing disciplines. Earth-observing systems are increasingly being utilized in the field of public health, and in Austin, the Fourth Conference on Environment and Health will include a themed joint session on this budding partnership. In that session, Benjamin Zaitchik of Johns Hopkins University will discuss the modeling of malaria risk in Peru (Monday, 5 p.m., Room 6b). Zaitchik and his colleagues modeled the influence of land cover and hydrometeorological conditions on the distribution of malaria vectors, as well as the relationship among climate, land use, and confirmed malaria case counts at regional health posts. In the study, meteorological and hydrological conditions were simulated with the use of observations from TRMM and other satellites.

The Value of Attending Scientific Meetings

by Keith Seitter, CCM, AMS Executive Director

There was a time when I thought scientific conferences would change character dramatically as the tools available for remote connections among participants became more sophisticated. I have come to realize, however, that as useful as videoconferencing can be in some situations, and despite the efficiency it offers in terms of reducing the need for travel, it cannot replace the value of physical participation in a scientific conference. That is because hearing and seeing someone give a presentation do not represent the principal value of these meetings — it is the interactions among those who are present. When I was a graduate student, a senior scientist once told me that he went to conferences specifically for the discussions in the hallway. He said that is where the real scientific progress occurs. While that may be an extreme way of looking at this, I eventually began to understand why he felt that way.

Over the course of a meeting, while we hear speakers present the essence of their results in their allotted 15 minutes, or describe what they can to fit onto the real estate of a poster board, we are challenged to make connections between what we are seeing and hearing and our own work. The questions asked within a session, or that we overhear, may spark additional connections, and our discussions with colleagues — or new acquaintances we make through shared interest in the topic at hand — can forge partnerships and collaborations that lead to new innovative ideas or new avenues of study. We are not just passively learning about other ongoing research at the meeting. We could do that by simply reading prepared papers or reviewing electronic posters at our leisure. Our being there among other attendees doing similar work and grappling with similar challenges energizes the scientific and creative process within all of us. I suspect that most of us come back from a scientific conference with renewed vigor for our work and sometimes entirely new approaches to it.

For the annual meeting in Austin next month, it seems clear that a number of Federal employees who would normally be at the meeting will unable to attend due to the restrictions placed on government travel in light of budget issues. This is truly unfortunate — especially given the meeting theme of taking predictions to the next level, which is such a core issue for those working in NOAA and other government agencies.

There are some individuals outside our community who question the need for scientific conferences, or at least, the expense of having many scientists traveling to these meetings. It can be argued, however, that the cost of travel to a scientific conference is returned many times over by the things that can be accomplished by the attendees over the course of those few intense days, as well as by the creative productivity they bring back to their institution after the meeting. I hope the value of scientific conferences to the nation will be more fully recognized in the coming months and we will not see ongoing travel restrictions of the type that have challenged the community in recent months.

Versatile VIIRS: Sandy Reveals More of Its Potential

The VIIRS instrument aboard the new Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership (NPP) satellite has a lot of jobs: among them, to measure cloud and aerosol properties, ocean color, sea and land surface temperature, ice motion and temperature, fires, and Earth’s albedo. Now, with the experience of Superstorm Sandy behind it, add tracking power blackouts to the list of tasks for this multifaceted instrument.

VIIRS–or more formally, Visible Infrared Imager Radiometer Suite, is a scanning radiometer that collects visible and infrared imagery and radiometric measurements of the land, atmosphere, cryosphere, and oceans. Its low-light sensor–known as the day-night band–can detect light from cities and towns in the absence of clouds. This function recently proved to be highly valuable when NASA’s Short-term Prediction Research and Transition Center used data from VIIRS to assist disaster responses agencies (including FEMA and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers) in identifying areas that lost power during Superstorm Sandy. Composites of VIIRS images taken before and after Sandy (see below for an example) pinpointed the blackouts.

This is just one example of the promising capabilities of VIIRS; and the growing awareness of these capabilities is why VIIRS is the subject of a town hall meeting on Monday, January 7 (12:15-1:15 p.m., Room 18B) at the AMS Annual Meeting in Austin. Forecasters, meteorologists, and other end users will discuss how they are utilizing the new VIIRS datastream and the critical role it can play in weather forecasting and in improving emergency preparedness and disaster response efforts.

A number of other presentations in Austin will highlight the versatility VIIRS. Jeffrey Hawkins of the Naval Research Laboratory will take an in-depth look at VIIRS’s day-night band and efforts to create enhanced products geared toward various nowcasting applications (e.g., dust enhancement observations, smoke and volcanic ash plumes, cloud properties, tropical cyclone structure, etc.) (Wednesday, 1:30 p.m., Ballroom G). Donald Hillger of NOAA/NESDIS will compare and contrast imagery produced by VIIRS with that from other satellites (Tuesday, 11:45 a.m., Ballroom G). And Jim Biard of the Cooperative Institute for Climate and Satellites will provide details on the VIIRS Climate Raw Data Record (C-RDR), including its contents and structure, its production methods and process, and file access (Wednesday, 11:30 a.m., Ballroom G).

VIIRS is one of five instrument/sensor payloads aboard Suomi-NPP, which is the first of a new breed of satellites that will replace NASA’s Earth Observing System satellites. Launched in October of 2011, the progress and promise of Suomi-NPP and its new data applications will be explored at a town hall meeting on Tuesday (12:15-1:15 p.m.; Ballroom G).

Speaking of Superstorm Sandy, electricity outages, and town hall meetings, there are two related Town Halls of special importance Monday night at the AMS meeting: a wide-ranging meeting on the storm itself (7:30-9:30 p.m.; Ballroom E) and an exploration of the impacts of weather on the electrical grid (Monday, 6:30-8:00 p.m.; Room 14). More on this in future posts on The Front Page.

Atmospheric Rivers Go Mainstream

This week NOAA announced installation of four new special observatories in California dedicated to improving the understanding–and forecasting–of atmospheric rivers, the massive (but narrow) flows of tropical moisture aloft in the warm conveyor belt of air ahead of cold fronts.

The timing of the announcement could not have been better. Ocean-fed storms with the distinctive filaments of tropospheric moisture brought heavy rains to California and Oregon this past week. Lake levels in northern California surged by as much as 34 feet; rush hour in major cities like San Francisco were bedeviled with flooded streets and bridges blocked by overturned vehicles due to the high winds carrying blinding sheets of rain.

The timing was not just good from a weather point of view but also from the standpoint of public understanding. The announcement culminated the fast-track rise of “atmospheric river” from an obscure technical term to popular understanding. In anticipation of the weekend deluge (and the lesser encore Wednesday), media outlets from Oregon to Minnesota to Australia picked up the vibe and were talking about atmospheric rivers–and not just by the more time-honored and familiar regional name, “Pineapple Express.”

It was only 20 years ago the term “atmospheric river” was introduced in a scientific paper by Reginald Newell and colleagues; then atmospheric rivers got a brief spate of publicity during the late 1990s and early part of this century with airborne field projects over the Pacific Ocean, such as CALJET and PACJET. Attention ramped up again during 2010’s infamous Snowmaggedon on the East Coast.

So it goes with atmospheric sciences, where the prospect of applications can drive quick adoption of useful concepts: useful not just in forecasting but also in climatology. For example, at the upcoming AMS Annual Meeting, Tianyu Jiang of Georgia Tech will look at different resolutions of general circulation models to see how well they depict these detailed structures (as little as 25 miles wide) and linkages with East Asian Cold outbreaks in a Tuesday poster session (9:45 a.m., Exhibit Hall 3). In a Monday poster (2:30 p.m., Exhibit Hall 3) Nyssa Perryman of Desert Research Institute will explore how downscaling from a global climate model to an embedded regional climate model can affect the simulation of atmospheric rivers.

The importance of this relatively new concept is such that the AMS Education Program devoted several sections to atmospheric rivers and how they transport water vapor from the tropics in its newest edition of the AMS Weather Studies textbook. Released in August 2012 by the AMS Education Program, the book is currently being used by thousands of college students nationwide as an introduction to meteorology. A QR code was embedded in the text to provide readers with access to the most current forecast information and video loops available on the subject.

For more on atmospheric rivers, check out Ralph and Dettinger’s article in the June 2012 BAMS on the relative importance of atmospheric rivers in U.S. precipitation. Marty Ralph discusses the article in this AMS YouTube Channel video:

Policy Symposium Keynote to Focus on Tree-Climate Connnections

by Caitlin Buzzas, AMS Policy Program

The keynote speaker for the 8th Symposium on Policy and Socio-Economic research at the AMS Annual Meeting in January will be author and journalist Jim Robbins. The Montana-based science writer for the New York Times just wrote a book on the connection between trees, forests and our atmosphere, The Man Who Planted Trees: Lost Groves, Champion Trees, and an Urgent Plan to Save the Planet.

Robbins’ talk for our meeting (Monday,7 January, 11 a.m., Room 19a) is going to span many different aspects of our annual meeting including public health, climate, and weather. The topic, “The Few Things We Know and the Many Things We Don’t about the Role of Trees and Forests on a Warmer Planet,” could be of interest to just about every topic the symposiums cover.

If you want a preview, check out his TED talk on YouTube, where Robbins’ commitment to the science of trees in climate is explained:

They say that everyone must have a child, write a book and plant a tree before they die. But for the writer and freelance journalist of the New York Times, Jim Robbins, if we just do the last part, we’d already be off to a great start. The author of “The man who planted trees” tells how he became a rooted defender when he observed the devastation of the old growth pine trees on his property in Colorado because of climate change. For him, science still hasn’t studied deep enough about these beings that filer air, stop floods, recover desert areas, purify water, block UV rays and are the basis of medicines as well as decorate the view. Much beyond shade and fresh water.

The 2013 AMS Annual Meeting actually goes a long ways toward fulfilling Robbins’ vision of discovering more about trees in our climate, with dozens of related presentations. At Monday’s poster session (2:30 p.m., Exhibit Hall 3), for example, Juliane Fry is presenting lab findings that may eventually refine regional climate mitigation policies that rely on tree plantings to produce cooling secondary aerosols. Also, as victims of fire disasters, forests feature prominently in the Weather Impacts of 2012 sessions (Tuesday, 8 January, Ballroom E). Similarly, on Wednesday (2:30 p.m., Exhibit Hall 3) Anthony Bedel will present a poster on the connection between changing climate and increasing potential for forest fires in the the Southeast, due to thriving fire fuels.

Young scientists are also following this line of work: Sunday’s Student Conference posters (5:30 p.m., Exhibit Hall 3) include a presentation by Zeyuan Chen of Stony Brook on understanding airflow in a cherry grove to better help orchard managers save their trees from bark beetles. Another student, Meredith Dahlstrom of Metropolitan State University in Colorado, presents in the same session on interannual and decadal climate mechanisms related to fluctuations in the prodigious capacities for carbon storage in the Brazilian rainforests.

Spotlight on Early Career Professionals

If you haven’t noticed, a lot of AMS members are just starting out in the atmospheric sciences, making their way to success in a field that is full of continually evolving–and often little-known–prospects for advancement. Now is a good time, however, for those early career professionals trying to learn more about what’s ahead and meet the colleagues they’ll be encountering in coming years: AMS is providing new opportunities for them to get to know more about each other and their common futures.

The November issue of BAMS features an interview with KMGH, Denver, Colorado, weekend meteorologist Maureen McCann, part of our ongoing series of features about young people in the atmospheric sciences community. Maureen has a lot to share about getting started in the field. For example:

On advice she would give to an early career professional starting in this field: The best advice would be take whatever comes your way for your first job. Your first job is key to fine tuning your skills and becoming familiar with the nuts and bolts of television news. Keep in mind that it’s temporary and you will use this experience to move onto the next job, if that’s what you desire. Small market life has a lot of benefits! I look back on my time in my first market, Bangor, Maine, with great memories. The friendships I made there were with people in the same boat as myself: fresh out of college looking to get their career started.

Another point of advice is to always keep your resume current. You never know when opportunities will present themselves. I aim to update my demo reel every six months. I probably would have missed out of the Denver opportunity if I didn’t have an updated reel online for the news director.

On who she seeks advice from and why: I’d have to say the broadcast community as a whole. Social networking has revolutionized how meteorologists can exchange information or gather feedback. There are some message groups on Facebook that serve as an excellent forum for this dialogue. Whether you have a question about graphics, or forecast models, or you’re looking for input on a prospective job location, chances are someone else has the same question too. It’s a great resource to poke through daily and see what the discussion topics are. It’s also a good way to make connections beyond traditional ways like conferences.

For the full interview, see the November issue of BAMS and look for similar features in the future thanks to your new AMS Board on Early Career Professionals.

Another opportunity to get to know early career professionals is coming up at the Annual Meeting in Austin, with the First Conference for Early Career Professionals on Sunday, 6 January 2013. Early- to mid-career professionals will offer guidance and hold open discussions to solicit input on how the AMS can further benefit members who are beginning their careers in the atmospheric sciences. That evening, attendees and all other Annual Meeting participants are invited to attend the third annual AMS Reception for Early Career Professionals.

If you have advice for early career professionals or would like to nominate an early career professional to be featured in BAMS, the Board for Early Career Professionals would love to hear from you. You can contact Andrew Molthan, current chair of the AMS Board for Early Career Professionals, at [email protected].