by George Leopold, AMS Policy Program

While it remains far from clear whether the Obama administration will gain final congressional approval, its fiscal 2014 budget request released earlier this month does contain small increases for improving weather forecasting and climate research.

The White House budget request also reveals early attempts by science agencies to collaborate more closely in areas like Earth observation and climate research.

Given the pervasive uncertainty over federal spending–for instance, across-the-board budget cuts known as “sequestration” began to bite this week with the furloughs of U.S. air traffic controllers–the administration’s proposed $200 million increase for NOAA and the National Weather Service is welcome. It also indicates that NOAA’s core functions remain a budget priority for federal bean counters.

If approved–and at this point that’s a big if–NOAA’s fiscal 2014 budget would top out at $5.45 billion. That’s about $200 million more than the amount approved for this year. If nothing else, the administration’s opening bid in negotiations over NOAA’s budget is higher than some stakeholders expected.

Acting NOAA Administrator Kathryn Sullivan said in a statement that the agency’s FY14 budget request seeks to: “1) ensure the readiness, responsiveness, and resiliency of communities from coast to coast; 2) help protect lives and property; and, 3) support vibrant coastal communities and economies.”

Not surprisingly, Sullivan emphasized NOAA’s role last October in preparing for and responding to Hurricane Sandy. We’ll be hearing a lot more in upcoming budget debates about the need to continue investing in core NOAA functions like environmental monitoring.

Indeed, the lion’s share of NOAA’s budget request for next year–about $2.2 billion–goes to its National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service, or NESDIS, which operates most U.S. weather satellites. A key issue is whether NESDIS can shorten an expected gap in the coverage of its polar-orbiting weather satellites. Even with a budget increase, however modest, it remains unclear whether the first Joint Polar Satellite System (JPSS-1) can be launched in time to reduce a coverage gap that, according to recent estimates, could last up to 53 months.

The design lifetime of the current Suomi NPP weather satellite is expected to end in 2016. According to NESDIS officials, NOAA remains on track to launch JPSS-1 during the first quarter of 2018. Additional funding in fiscal 2014 could reportedly speed up the launch of JPSS-2 to 2021.

Another priority is beefing up the National Weather Service’s supercomputer and networking infrastructure to improve its weather forecasting models as well as its climate research. According to budget documents, funding for climate research would increase to $143 million, with the overall funding request for NOAA’s Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research increasing to about $390 million.

Expect to also hear a lot more about collaboration as agencies like NOAA look to do more with less. To that end, NOAA’s Unmanned Aircraft Systems office is seeking an additional $2 million next year to acquire more low-mileage drones from the U.S. military “to accelerate next-generation weather observing platforms.”

Meanwhile, NASA’s fiscal 2014 budget request of $17.7 billion is $50 million below what the space agency received last year. Despite the reductions, the budget request does include $1.8 billion for Earth science programs such as Landsat and climate sensors for JPSS.

NASA said its budget request also includes funding to take over from NOAA responsibility for “key observations of the Earth’s climate,” including atmospheric ozone, solar irradiance, and energy radiated into space. Under the budget plan, the space agency would also “steward” two Earth observation sensors on NOAA’s space weather mission, Deep Space Climate Observatory, currently scheduled for launch in 2014.

Agency heads will begin defending their fiscal 2014 budget requests this week. NASA Administrator Charles Bolden is scheduled to testify on April 25 before the Senate Appropriations Committee panel overseeing space agency spending.

NOAA’s Sullivan is scheduled to appear before the Senate Commerce, Science, and Transportation Committee on April 23.

NWS Experiment Chooses Words To Improve Warnings

The National Weather Service recently announced plans to expand the use of its experimental impact-based storm warnings to include all 38 branches of the NWS Central Region. The warnings go beyond a simple explanation of a storm’s strength by communicating specific effects that the storm could cause, using descriptions like “major house and building damage likely and complete destruction possible,” “major power outages in path of tornado highly likely,” and “complete destruction of vehicles likely.” The warnings were implemented last year in Kansas and Missouri, and officials believe they helped prevent fatalities during a tornado outbreak in Kansas last April 14. The effectiveness of the warnings last year will be examined in more depth in a presentation at the Second AMS Conference on Weather Warnings and Communication, which will be held this June in Nashville (in concert with the 41st Conference on Broadcast Meteorology) .

These new warnings are just one example of the advances made in communicating dangerous weather events to the public, and the Nashville conference will examine a number of methods, including the use of social media and mobile apps. The meeting will also look at how the general public responds to various types of warnings, and explore both old and new technologies in warning systems. The full program for the conference can be found here.

Clarity of communication is a key to the impact-based warnings. According to this story in the Wichita Eagle, emergency officials are praising the vernacular of the new warnings. Michael Hudson, chief operations officer for the NWS Central Region headquarters in Kansas City, Missouri, noted that “emergency managers liked the extra information that was in the warnings–the information that got to the magnitude of the weather.” In specific reference to the intense tornado in Sedgwick County, Kansas, last April, that county’s emergency management director, Randy Duncan, felt the language in the impact-based warnings “helped to convey how serious the situation was, and the fact that we didn’t have any fatalities means–at least in my mind–that people in Wichita paid attention.”

The expanded use of the warnings this year will include some minor revisions resulting from some lessons learned in last year’s experiment. One change is the new use of the word “considerable” instead of “significant,” because “significant” was considered by many users to be too vague. Hudson explained that forecasters are instructed to consider “what you’d tell your wife or husband or children” about the potential threat of a storm.

The Value of Knowing Our Value

by Ellen Klicka, AMS Policy Program

Sometimes articulating the right question is the tipping point on the path to the right solution.

At last week’s AMS Washington Forum, members of the weather, water and climate enterprise and other leaders assembled to discuss the pressing issues the community is facing. Speakers and attendees alike posed questions, shared insights and then posed better questions.

The first panel took a focused look at progressing towards a better understanding of the economic value of the weather and climate enterprise.

One question that is as good as any to begin an exploration is, “Why do we want to estimate the value of the enterprise?” Forum participants frequently revisited this point during the forum. What follows are themes raised throughout the three-day dialogue.

As a community, weather, water and climate organizations and professionals do not justify in quantitative terms their value to society as effectively as other enterprises. Where can this community say it fits in?

The difficulties created by increasingly tight federal budgets are inescapable. Some say if the enterprise does not step forward to demonstrate why its labor is vital to the nation, decision makers with less knowledge will have no choice but to set priorities on their own. Others believe that framing of the issue is divisive, pitting segments of the community against each other for finite resources.

In either case, quantifying the value of the weather and climate enterprise requires a paradigm shift from evaluating the costs of weather to focusing instead on the benefits of weather and climate information.

Part of the challenge stems from the cumbersome and imprecise nature of the steps involved in calculating even the smallest microcosm of the enterprise. If investigators did arrive at a total dollar value or benefit-to-cost ratio of investment in the enterprise, how confident could anyone be in its basis?

The Weather Enterprise Economic Evaluation Team, under the auspices of the AMS Commission on the Weather and Climate Enterprise, will complete a draft request for proposals by this summer to commission the largest study of this kind ever undertaken.

While most members of the enterprise are scientists, the tools of economics will be valuable to this study. For example, an examination of marginal values brings to light the gains from increased investment. Where is the biggest bang for your buck for one extra dollar? Logic points to the biggest need: getting the public to understand and use forecast information effectively so they take appropriate action.

These recent discussions on valuation have not been the first among the AMS membership, and they won’t be the last. The themes of the next enterprise-wide gathering—the AMS Summer Community Meeting in Boulder, Colorado, on August 12-15–include improving weather forecasts; supporting ground transportation, aviation, and conventional and renewable energy; and, yes, determining the economic value of the weather and climate enterprise.

Until then, ponder this multiple choice question:

How good do we want to be as a nation?

A. No worse than we are today

B. As good as we can be (with no realistic limitations on resources)

C. As good as we can afford to be at a fixed cost-benefit ratio

D. As good as or better than other nations at a similar economic development stage

Checking the Sky for the Long Ball

In Major League Baseball today, pitchers are kings. Hits per games have decreased for six straight years, while strikeouts per game have gone up seven straight seasons. An influx of young pitchers throwing harder than ever and with more movement on their pitches combined with analytical data that puts the defense in better position to prevent hits has stifled offenses throughout the Majors. (Oh, and there’s also–presumably–fewer hitters with artificially enhanced bodies than there used to be.)

This means that baseballs are flying out of ballparks at much lower rates today than they were at the beginning of the new millennium. Home runs peaked in the 2000 season, with almost 5,700 balls leaving the park (1.17 per game). Those numbers have been in a fairly steady decline since, reaching a nadir of 4,552 (0.94) in 2011, and still only at 4,934 (1.02) last season. So what’s a fan who just wants to see a few dingers to do? Well, don’t forget about the weather. Baseballs tend to travel farther when the air is less dense, and of course a good tailwind helps as well. And there’s an app that can help fans track conditions at their local Major League stadium and, most importantly, let them know the likelihood of home runs at that day’s (or the next day’s) game.

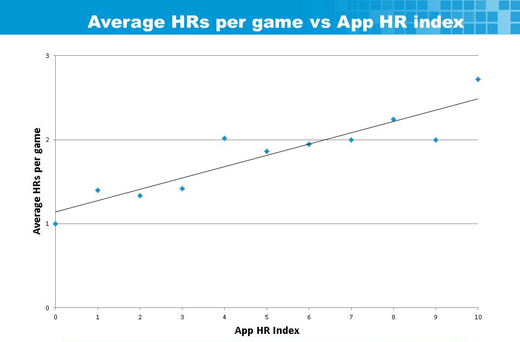

Home Run Weather takes into account temperature, atmospheric pressure, humidity, wind direction and speed, the orientation of the ballpark, and the drag coefficient of a baseball to calculate the home run index, which tells how favorable conditions are for home runs at every game in every Major League park. The index, which is available for both current conditions and hourly over a 24-hour period, is given on a scale of 0 (least favorable) to 10 (most favorable). The creation of the index incorporated both analysis of weather and home run data over several seasons at Citizens Bank Park in Philadelphia as well as a theoretical, physics-based model that calculates how far a baseball will travel in specific atmospheric conditions. The accuracy of Home Run Weather is indicated in the chart below, which shows the average number of home runs hit per game over the course of the 2012 season for each of the app’s index values.

The app is available for both iPhones and Androids. And just a quick heads up: tonight’s Nationals-White Sox game at 7:00 in Washington, D.C., gets a “10” on the home run index (forecast of 80-degree temps, 12-mph winds, 49% humidity, and pressure of 29.85″), so if you like home runs, get yourself to Nationals Park!

Budget Squeeze Spurs U.S. Weather Collaboration

by George Leopold, AMS Policy Program

The watchword for future federal weather efforts will be collaboration.

Budget sequestration has so far limited the options for program managers seeking ways to fund new observation platforms ranging from expensive satellites to ships and unmanned aircraft carrying weather sensors. For the U.S. military, which has taken the brunt of across-the-board spending cuts, a new weather satellite like the Defense Weather Follow-On System means fewer ships and planes.

The zero-sum budget process faced by federal agencies means that “if you want something, you have to give up something else,” says Robbie Hood, director of NOAA’s Unmanned Aircraft Systems program. “Our job is to look at all these new technologies” and identify the best option.

The Navy also is looking at unmanned aircraft along with new ship-based sensors as ways to monitor the lower atmosphere. The Navy’s weather requirements appear to mesh well with those of civilian agencies like NOAA.

The military services and civilian agencies such as NOAA are again attempting to share weather observation data as a way to stretch scarce dollars. Weather observing needs continue to dovetail across stakeholders as collaboration heats up among the services, civilian agencies and other entities. For example, the Army needs satellite data on conditions like soil moisture content when planning ground operations.

One area ripe for closer cooperation is ocean observations, an obvious focus for the Navy and a growing segment of weather observations for storm trackers and climate modelers. Leveraging emerging platforms like drones, unmanned boats and ship-based sensors could help fill part of the anticipated gap in satellite coverage of the Earth’s oceans. For the military, coverage gaps could result from either the failure of an Earth observation satellite, delays in launching the Defense Weather Follow-On System or the fact that U.S. weather satellites tend to target the coasts.

NOAA’s Hood said her office is working with other agencies to synch up new weather observation requirements. She noted that using unmanned aircraft for applications like monitoring Arctic sea ice, for example, is similar in many ways to military reconnaissance missions.

NOAA has purchased used Puma AE unmanned aircraft from the Army at bargain prices and will hand launch them from U.S. Coast Guard ships on test flights later this year. The unmanned aircraft have been used extensively by the Army to “see over the next hill.” The Puma AE has a 9.2-foot wingspan, weighs 13 pounds and can remain aloft for up to two hours.

Hood said monitoring Arctic sea ice using sensor platforms like the Puma is an ideal way to promote interagency collaboration given “our commonality of interests.” Continuing budget constraints mean unmanned aircraft outfitted with the appropriate weather sensors and navigation aids are the most cost-effective way to reach critical but remote areas like the Arctic, she added.

While NOAA is investing in Pumas, NASA’s weather drone fleet includes two high-flying, long-endurance Global Hawks purchased from the Air Force. (NASA operates the unmanned aircraft and NOAA provides most of the sensor payloads.) Meanwhile, the Energy Department is working on new weather sensor systems that could be flown on drones operated by other agencies.

The acquisition strategy of civilian agencies like NOAA and NASA also seeks to leverage the U.S. military’s long experience flying unmanned aircraft. Not only are used drones cheaper, they require less testing. Hence, NOAA and NASA drones will help monitor melting Arctic sea ice this summer as part of the Marginal Ice Zone Observations and Process Experiment. The experiment focuses on targeted observations to gain a better understanding of local conditions like sea surface temperature and salinity during summer melts.

The Navy and NOAA could also collaborate on tracking ocean surface vector winds, Hood said. “There a lot of small, joint efforts designed to keep things moving” despite tight budgets, she added.

The tough U.S. job market, especially for returning veterans, might also be addressed if interagency collaboration expands. Hood said civilian agencies looking for drone operators could recruit veterans with experience flying Global Hawks in combat.

Hurricane Center Changes Policy to Include Sandy-like Storms; AMS Forum Assists

If another storm like Sandy threatens land while on the cusp between tropical and extratropical classification, National Hurricane Center (NHC) forecasters will have a green light to issue or maintain watches and warnings as well as advisories, even after transition.

That’s the policy change NWS/NHC made this week after months of animated debate among forecasters, weather broadcasters, and emergency managers. The changes will take effect at the start of the 2013 Atlantic hurricane season, June 1.

The shift—from watches, warnings, and advisories only being posted by NHC when a storm was expected to be strictly tropical as it came ashore to now being allowed for what it terms “post-tropical” storms at landfall—was borne of a critical firestorm.

Despite the enormous threat from Sandy last October, NWS and NHC decided not to hoist hurricane watches and warnings for the northeastern coast of the United States because the monster storm wasn’t forecast to land its center on shore while still a hurricane. The re-classification of Sandy as post-tropical would have forced such alerts to be dropped mid storm, which they argued would cause confusion.

Critics of the decision claimed that people in harm’s way didn’t take the storm seriously because there weren’t any hurricane warnings in place. Nearly 70 people died in the United States directly from Sandy’s surge and wind.

The fallout included broad discussions of the difficulty forecasting Sandy. At an AMS Town Hall Meeting in Austin, Texas, in January, Louis Uccellini (then director of NOAA’s National Center for Environmental Prediction) said that NWS and NHC forecasters had anticipated Sandy transitioning from a hurricane to an extratropical storm, but they expected it to happen sooner than it actually did. In his presentation, he also noted that the primary operational forecast model used by the NWS (the Global Forecast System, or GFS, model) had performed the best of all models during the 2012 Atlantic hurricane season, but when it counted—with the season’s only two landfalling U.S. storms of hurricane intensity (Isaac and Sandy)—it had the worst forecasts.

“When you don’t hit the big one, people notice,” he said.

Compounding the uncertain model forecasts was what to do with the warnings if the transition occurred prior to landfall. NHC Director Rick Knabb discussed this at the same AMS Town Hall meeting, calling it the “Sandy warning dilemma.” He agreed that hurricane warnings would have been best, because they’re familiar and grab your attention. But, because of the looming transition, discussions among NHC and NWS forecasters as well as emergency managers and local and state authorities, including one governor, stressed that the warning type not change during the storm for fear of confusing the message during critical times of preparation and evacuation. Due to the structure for hurricane warnings in place at the time, which would have forced NHC to drop them once the transition occurred, NHC and NWS forecasters opted not to issue a hurricane warning for Sandy.

“We wanted to make sure the warning didn’t change midstream, and we could focus on the hazards.”

Ultimately, calls settled on a way to effectively communicate the threat of dangerous winds and high water regardless of a storm’s meteorological definition. A proposal surfaced during the Town Hall that would broaden the definition of tropical storm and hurricane watches and warnings and include post-tropical cyclones, whose impacts still pose a serious threat to life and property.

Knabb credits the candid nature of the months-long debate, with its criticisms and recommendations, for the now-approved proposal. He says it will allow NHC and NWS forecasters as well as the emergency management community to focus on what they do best.

“Keeping communities safe when a storm threatens is truly a team effort and this change reflects that collaboration.”

Hanging Together: The AMS Washington Forum

by Ellen Klicka, AMS Policy Program

“We must all hang together, or assuredly we shall all hang separately.” – Benjamin Franklin

News headlines these days are reflecting the increasingly austere and complex environment in which private businesses, governments and academic institutions manage to muddle through towards a better tomorrow. Creating new opportunities to collaborate for mutual advancement is more of a necessity than it used to be. The annual AMS Washington Forum, to be held April 2-4, 2013, fills that need for the benefit of all three sectors that make up the weather, water and climate enterprise and offers insight into the workings of Washington, DC, an increasingly austere and complex city.

This year’s theme, the economic value of the weather, water and climate enterprise, builds on discussions at other recent AMS meetings and may resonate particularly well in Washington circles: Considering the national attention on last year’s natural disasters, renewed interest from Congress in climate legislation, the federal budget sequester, and continued economic uncertainty, this event couldn’t be more timely and on topic.

In the last six weeks alone, the Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry, the Senate Committee on Environment & Public Works, and the House Science, Space and Technology Committee have scheduled hearings or briefings on pressing topics our community is studying or addressing. Topics range from policy-relevant climate issues to the economics of disasters for America’s farmers.

The notion of tacking a dollar value onto the benefits the weather, water and climate community affords the country is not a new one but it has proved an elusive task. Groups within the AMS membership have been grappling with the development of an approach to size up exactly what the enterprise adds to the economy and American society as a whole for at least a couple years. The AMS Annual Meeting and Summer Community Meeting have included discussions on the topic, as have AMS journals (such as these BAMS articles by John Dutton and by Jeffrey Lazo et al.). With the U.S. tightening it collective belt, it is more urgent than ever that the enterprise be able to objectively demonstrate its worth.

Policy makers rely on quantifiable reasons for making choices that affect the country, and enterprises that are defined by industry may have an easier time estimating their market size. The weather, water and climate enterprise cuts across many industry sectors. Avoided losses can be difficult to pinpoint. Because our community operates in an environment characterized by increasing pressure to justify the need for investment, the AMS Commission on the Weather and Climate Enterprise is planning a valuation effort. The first panel at this year’s Forum will explore the challenge and discuss approaches to a valuation effort.

Subsequent panels will tackle many of the hot issues facing our community right now: international opportunities, data commercialization, environmental security, renewable energy policy, water resource management… the list goes on.

The Washington Forum has evolved through the years since AMS began holding the conference in the national capital. Originally, the forum was held as a benefit to corporate members and fellowship/scholarship donors in recognition of their sponsorship of AMS. The event expanded to include the government sector and became known as the Public Private Partnership Forum. When the Commission on the Weather and Climate Enterprise was formed in 2005 in response to the National Academies’ Fair Weather Report, it was recognized that the academic sector deserved inclusion as well.

The Washington Forum is an open meeting to which all AMS members and other professionals in the weather, water and climate enterprise are welcome and encouraged to attend. For more information on this year’s event, visit the Forum website.

NOAA Hiring Freeze: Capabilities Head Down a Slippery Slope

by J. Marshall Shepherd, AMS President. The full text was posted earlier today on his blog, Still Here and Thinking.

This week NOAA, the parent agency for the National Weather Service (NWS), announced a hiring freeze at a time when its vacancy rate is already around 10%. I understand that this number is near 20% for the Washington, D.C. area NWS Office. At this point, pause and consider public safety. As we enter the severe weather/tornado season, the Sequester has forced the hand of our NOAA management and possibly jeopardized the American public’s safety, stifled scientific capacity, obliterated morale within NOAA/NWS, and dampened hopes for the next generation of federal meteorological workforce. Beyond safety, we have increasingly clear evidence that weather is important to our economy, a critical consideration for an agency in the Department of Commerce.

Now to be clear, I know, personally, the senior level managers at NOAA/NWS very well: they will do everything within their power to adjust and mitigate impact. This commentary is really not about them.

Like our dedicated military, border patrol agents, police officers, and firefighters, NOAA employees provide a valuable public service that affects our lives every day, including warnings and alerts. A community would be outraged at cuts to a nearby Fire Station staff, particularly during a rash of arsons. Additionally, NOAA/NWS personnel are increasingly missing as subject matter experts for major Emergency Management training and conferences.

The vibrant and critical private weather enterprise adds value to data, models, and warnings from NWS. I have often joked that NOAA is to the private sector weather enterprise, what the potato farmer is to a company that makes French fries. It is a vital partnership, which includes research and applications from academic partners as well. The AMS Washington Forum will bring together these sectors for a vital meeting next week, including the increasingly important discussion about creation of a U.S. Weather Commission.

I am fearful of what is happening in our community with draconian sequester cuts, challenges to travel/science meeting attendance and other stresses on science/R&D support within NOAA, including journal publications, fees, etc. If you couple this with looming concerns about weather satellite gaps, computing capacity to support advanced modeling, and employee morale, we are slipping down a slippery slope of “eroding” the U.S. federal weather enterprise. Since industry, academia, and federal agencies work closely together, these effects will ripple throughout the broader community.

The public may take for granted a tornado warning based on Doppler radar or a hurricane forecast based on satellite information. Likewise, the public probably just assumes that they will have 5-9 day warning for storms like Sandy; 15-60 minutes lead time for tornadic storms approaching their home; weather data for safe air travel; or reliable information to avoid hazardous weather threatening military missions. However, these capabilities can and will degrade if we cut weather balloon launches, cut investments in the latest computers for modeling, reduce radar maintenance, delay satellite launches, or shatter employee morale. We are accustomed to progress and innovation, but I fear capabilities will regress instead, jeopardizing our lives, property, and security. And I have not even spoken about the challenges that a changing climate adds to the weather mix.

At my university, I see young, vibrant, and talented students everyday who embody the next generation weather enterprise. They are taking notice of what is happening, and I believe this seriously jeopardizes our future workforce.

As we enter the active spring tornado season, let’s hope the sequester season ends, before the hurricane season begins.

AMS Teaching Excellence Award Renamed after Edward N. Lorenz

Almost five years after his passing, the AMS is honoring Edward N. Lorenz by renaming the Teaching Excellence Award after the pioneer meteorologist. Best known as the founder of the chaos theory and butterfly effect, Lorenz was also an influential professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) for decades.

According to Peter Lamb in his recommendation to rename the award:

Edward N. Lorenz was arguably the most accomplished research meteorologist of the twentieth century. His seminal contributions in several key areas of our science today either carry his name or a name that he provided. At MIT, his principal instructional role was to introduce multiple generations of beginning doctoral students, many with little or no background in meteorology, to the challenges and rigor of the theoretical essentials of our science. Those lectures were renowned for their consistently very high standards of preparation and presentation, just like Professor Lorenz’s external seminars.

Lorenz received the MIT Department of Meteorology’s “Best Teacher” award the first year student evaluations were conducted as well as subsequent years. He went on to win the Kyoto Prize and AMS Carl Gustaf Rossby Research Medal, just a few of his numerous honors. Many of Lorenz’s students went on to distinguished research careers. Several were recognized with the AMS Rossby Medal and Charney Awards, and two of his past students received the AMS Teaching Excellence Award.

The AMS Council passed the recommendation in January, renaming the award “The Edward N. Lorenz Teaching Excellence Award.” Nominations for all awards are now open with a deadline of May 1. The Council encourages members and friends of the AMS to submit nominations for consideration for the Society Awards, Lecturers, Named Symposia, Fellows, Honorary Members, and nominees for elective Officers and Councilors of the Society here.

For Science and Discovery, Videoconferencing Won't Get It

by J. Marshall Shepherd, AMS President. The full text was posted earlier today on his blog, Still Here and Thinking.

I am sitting here during coffee break at the NASA Precipitation Science Team Meeting in Annapolis, Maryland. This meeting is a gathering of the world’s top scientists working with the TRMM, GPM, and other NASA programs related to precipitation, weather, climate, and hydrology.

A prevailing lament of many of my federal colleagues attending this meeting is the concern about the ability to attend scientific meetings because of travel restrictions and sequestration/budget issues. As I ponder their laments, I reflect on whether (1) these colleagues are spoiled federal employees not adjusting to austere budgets, (2) these colleagues are victims of a perception about federal employee travel because of a few isolated bad choices (e.g. GSA conference story publicized in the media, or (3) I have a bias as AMS president because we host meetings and have an interest at stake.

Here are four things that I come up with:

We risk stifling scientific and technological innovation: Yes, budgets are tight and some travel/conference activities (a very small percentage) are questionable. However, as someone that has attended scientific meetings and conferences for over two decades, these meetings are very intense, intellectually-stimulating, and advance the science. They are not vacations or frivolous. I arrived at the meeting room yesterday at 7:45 am, sat through various sessions, met with two different working groups/planning committees, and discussed a potential new scientific collaboration. I got to dinner at 8:15 p.m. There is a movement towards the use of various videoconferencing solutions. Those advocating these measures have completely missed the point that the most valued aspects of attending conferences and meetings are the “hallway” meetings, poster sessions, lunch/dinner meetings that lead to potentially transformative research, or the chances to caucus with colleagues on a new method or technology. (AMS Executive Director Keith Seitter made these points in The Front Page in December.) The presentations (what gets videoconferenced) are important but often secondary or tertiary to the value of such meetings.

All professions stay current on their topic, why should scientists and engineers be different?: I cannot imagine any profession or industry not wanting its employees to be current on the latest methods, techniques, and discussions. I am certain that leading companies continuously train their employees. Scientific meetings are “the training” for many professionals. For example, our AMS annual meeting has up to 20+ “conferences” within one conference. It also has various short-courses, town halls, and briefings. I argue that we risk “dumbing down” our U.S .scientific workforce with such arcane travel restrictions. At a time when we need to push the innovation envelope for society, we risk folding it up and discarding it. As an example, our Air Force pilots are the best in the world. They develop their skills through course work and flight simulators. However, at some point, they have to get into a real aircraft and interact with other pilots to gain knowledge, experience, and “tricks” of the trade.

Another offshoot of federal travel restrictions is our standing with the international community. U.S. presence is essential at many international meetings. Many of our collaborators and colleagues abroad are also being affected in terms of their own meeting planning, expectations, and the possibility of no U.S. presence. Does anyone see the inherent problem with this from the standpoint of international partnerships and our reputation?

What I also find amazing (and admirable) is that many federal colleagues (often called “lazy” or not-dedicated) have paid their own way to meetings or conferences. But if they do this, are they representing themselves? Should they discuss their work at the conference (since technically they are on vacation)?

Stifling the Private Sector: The private sector and small businesses are critical to our economy. I spoke with several major company representatives and small businesses at our 2013 Austin AMS meeting. They were also lamenting. They were talking about how the lack of federal attendees severely hinders their access to potential new clients and business. This has more than a trickle down effect on the health and vibrancy of our private sector and its contributions to economic vitality.

The Next Generation: As a young meteorology student at Florida State, I was in awe of attending the AMS and other meetings and having the opportunity to meet the woman who wrote my textbook, the Director of the National Hurricane Center, or a NASA satellite scientist. Our current generation of students (undergraduate or graduate) are in jeopardy of losing these valuable career-enriching opportunities. AMS, for example, hosts a Student Conference and an Early Career Professional Conference. By design, we expose hundreds of future scholars, scientists, and leaders to the top professionals in our field. In 2013, many of these professionals can’t travel or have to jump through hoops to declare the travel “mission critical” in NASA-speak (I spent 12 years as a NASA scientist).

I conclude that I am not being a “homer” on this issue. There are real concerns about the status and future of scientific discovery, innovation, private industry health, international reputation, professional development of our workforce, and exposure of our next generation.

Video conferencing just won’t get it.

Added 29 March, to clarify: I am aware of the challenges related to travel and emissions. Three points are worth adding:

- AMS has a Green Meetings initiatives.

- Large shifts to videoconferencing are not completely immune to costs, such as energy required to support increased computing/IT requirements, and

- Videoconferencing may be highly appropriate for smaller committee and board meetings but not large scientific meetings, which was the point of this post.